Photo: Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends

Statues that Speak

5th-Century Greek Sculpture as Symbolism for Classical Age Ethos

By Millie Huang

I. Introduction

The Classical Age in Greece (510-323 BC) witnessed many monumental changes in Greek society, including the end of aristocratic culture and the spread of democracy in Athens. Qualities such as egalitarianism, rationality, and austerity became prevalent, and it is said that much of Western artistic thought, on such topics like politics, philosophy, and literature, were derived from this age. Particularly, one eminent area of Classical Greek art is sculpture—a genre that was already defined in the Geometric and Archaic Periods, but came to see rapid, dramatic changes in the fifth century. Much of this paper will focus on sculpture from Athens, which was a political and cultural hegemon following the Greco-Persian Wars.

The revolutionary changes we see in sculptural history at the time are by no means coincidental: sculpture developed as a visible parallel to the societal conditions and ideologies that came to define the Classical period. Essentially, this is demonstrated by two features: first, the subject and context of Classical sculpture, and second, the aesthetic principles that characterized the genre.

II. The Significance of Subject Matter

The transition to Classical sculpture involved a diversifying of subject matter, providing a perspective on the period’s social context. In many cases, these changes are visual testimony to the new societal principles of the era.

In the Classical period, sculptures increasingly depicted real people. For example, after the murder of Hipparchus in 514 BC and expulsion of Hippias in 510 BC that effectively ended the Peisistratid tyranny, the tyrannicides Harmodius and Aristogeiton became heroes of Athens and were commemorated as patriots, martyrs, and liberators.[1] Two statues commissioned by Kleisthenes and built by Antenor were erected in the agora, believed to be the first portraits of individual citizens constructed with community funds for a public monument.[2] Although stolen by the Persians during their occupation of Athens in 480 BC and removed to Susa, a second version was commissioned by the Athenians and was completed by sculptors Kritios and Nesiotes in 477/6 BC. This set of statues exemplified the revolutionary traits of Early Classical sculpture—Severe style—with both figures posed dramatically, anatomically complex, and taciturn in disposition (Figure 1).[3] Taken together, the tyrannicide sculptures are said to be the “first purely secular commemorative statues in Greece.”[4] The meritocratic accomplishments represented by the statues and inclusion of fellow citizens in iconography previously reserved for religious deities gives evidence for a community that promoted egalitarianism. Since Harmodius and Aristogeiton were symbols of the rejection of the tyranny and excess of the transitional period, it can be said that placing their statues in such a public area is indicative of the comprehensive nature of the democratic reforms, and the resolve of Athenian citizens to amend their old ways. This is expressed by British Classicist Nigel Spivey in his 2013 book Greek Sculpture, which states that the images of Harmodius and Aristogeiton “would become symbolic cornerstones of the Athenian democracy as it developed in the 5th century.”[5]

Figure 1. Harmodius and Aristogeiton, Roman marble copy (of original bronze) in the Naples National Archaeological Museum.[6]

The Kritios boy (Figure 2) is another sculpture from the Late Archaic period commonly attributed to Kritios and Nesiotes.[7] It is the first example of contrapposto—a shift in the weight of body position to one leg to assume a harmonious “S”-shaped curve—and along with the Tyrannicides, designates the two sculptors as quintessential figures in the transition phase from Late Archaic to Severe style sculpture. As mentioned, the Tyrannicides and the Kritios boy are both highly idealized, honoring balanced, virtuous qualities imbued in visual form. However, the beauty of these sculptures is not because they depict gods or other mythical figures of worship. Instead, they simply depict the perfection of the human form—fitting for a generation that believed in human potential.

Figure 2. The Kritios Boy, Acropolis Museum, Athens.[8]

Lastly, one cannot overlook the analysis of the Parthenon and its architectural sculpture. One of the most significant architectural achievements of Ancient Greece, the Parthenon was built between 447 and 432 BC on the Athenian Acropolis (Figure 3). Standing as the “most lavish, technically refined, and programmatically cohesive temple on the Greek mainland”,[9] the Parthenon was constructed in a city that was notably different from the one which existed before the arrival of the Persians. The Athenians had scored a decisive victory against their old enemies at the Battle at Eurymedon around 466 BC, and the city had become the premier naval power in Greece.[10] As described by art historian Rachel Kousser, “Athens’ internal politics were radically democratic, its foreign policy, imperialistic; the conjunction of the two encouraged massive spending on public works projects such as the Parthenon”.[11] In fact, the Parthenon was the product of the proceedings of a free democracy, initiated and supervised by the Ekklesia and its judicial channels.[12] Thus, it can be said that the building itself, in addition to being a victory and war monument, was an embodiment of Athens’ political and cultural preeminence, as well a striking symbol of Athenian democracy.

Figure 3. Facade of the Parthenon, Acropolis, Athens.[13]

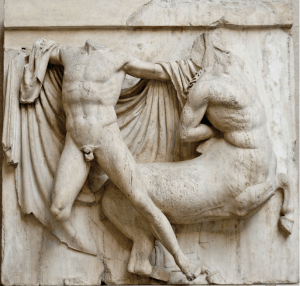

The Parthenon’s exterior was adorned with some of the finest architectural sculpture from antiquity: 92 metopes, a frieze running on all sides of the building, and both pediments consisting of 50 momentous figures.[14] In general, it is agreed that the sculptures taken together, serve as a cumulative allusion to the triumph of Athens over Persia in 480 BC. This can be seen in the metopes, which presented images of generalized foundation legends: battles between gods and titans and between Greeks and other enemies, such as centaurs, Trojans, and Amazons (Figure 4).[15] Overall, the scenes depicted communicate the victory of civilized order over barbaric chaos, and as stated by Joan B. Connelly in her 1996 journal article “Parthenon and Parthenoi: A Mythological Interpretation of the Parthenon Frieze,” they represented “the nexus of ‘saving the city’ from exotic outsiders and the preservation of Athens by and for the autochthonous Athenians.”[16] Significantly, these depictions of victory correspond to the triumphalism of the Athenians following the defeat of the Persian Empire, and similar to the art created in the Iron Age, compound a “West versus East” mentality that still lingers in Western thought today.

Figure 4. Battle between Lapiths and Centaurs. South metope XXVII, British Museum.[17]

As for the frieze, it was much less conventional in subject matter. Whereas the metopes embody a Severe style, the frieze is seen by many to represent the epitome of high Classical style.[18] The best preserved element of the sculptural decoration of the Parthenon, it is thought to represent a long procession of the citizens of Athens, celebrating an important civic and religious event likely to be the Panathenaia.[19] This is attested to in a scene on the east side (E31-35; Figure 5), which seems to be the culminating event of the procession. It consists of two girls bearing cushioned stools on their heads, and a bearded man taking a large folded cloth, interpreted as Athena’s peplos, from the hands of a little boy.[20] This depiction of community is revolutionary because it is placed directly alongside images of the gods, suggesting a significant amount of patriotic self-confidence and a new value being put on the contributions of citizens to the state.

Figure 5. Peplos scene. Block V (fragment) from the East frieze of the Parthenon, British Museum.[21]

The frieze evokes an ideal in which the heroism personified by the legendary figures in Homer’s poetry is expanded from the idealized individual to the group and the citizen, giving a contemporary meaning to Homeric virtues such as arete, time, and kleos.[22] It is compelling to view the friezes in conjunction with Thucydides’ account of Perikles’ funeral oration in honor of the Athenian war dead, a “statement of the highest civic aspirations and achievements of the Classical Athenians.”[23] Particularly, one passage states: “So died these men as became Athenians… For this offering of their lives made in common by them all they each of them individually received that renown which never grows old…that noblest of shrines wherein their glory is laid up to be eternally remembered upon every occasion on which deed or story shall fall for its commemoration.”[24] Like the context of the frieze, this extension of kleos aphthiton in a commemorative setting is groundbreaking, and both relate to a much broader trend occurring in Classical Athens—the growing importance of community.

III. The Significance of Features and Principles

The Classical style that appeared around 480 BC consisted of a number of features that made it markedly distinct from its Archaic predecessor. As described by Andrew Stewart in his 2008 article on Classical sculpture, “clear-cut proportions structure the human body in a lucid, logical way; contrapposto rationalizes and disciplines the flux of human movement; simple clothing bespeaks personal restraint and a commitment to egalitarianism; forceful postures, modeling, and gazes radiate health, vigor, and determination; and an averted head and sober expression suggest, quite simply, that the subject has stopped to think.”[25] There are a number of qualities that can be extracted from this passage which have counterparts in the development of Athens in the Classical age from the advent of democracy to the Persian Wars, and this section will primarily focus on discussing them using sculptures of the male form, one of the most prevalent subjects for Greek artistic endeavor.

Recalling the description of an Archaic kouros, classical depictions of the body were strikingly evolved. For instance, a kouros of the Archaic age (Figure 6) were generally “upright, four-square figure[s] with arms held to [their] sides and one foot in front of the other.” Examples such as the early Egyptian statues of Ranofer with similar stance and proportions have often been used for comparison with Greek kouroi,[26] and the careful measuring of proportional variables by Whitney Davis in a 1981 article found a clear association between Archaic kouros and Egyptian canon.[27] Thus, it is important to note the stylistic evidence of this prolonged influence of Egyptian sculpture alongside the dramatic departure of Classical sculpture from these previous norms, as part of Classical Age ethos coincides with the burgeoning, distinctive “Greek identity.” Another point of value is the divergence from the “Archaic Smile” that was ubiquitous in sculpture in the Archaic age [28] for the thoughtful expressions of the Severe style. Although the meaning of the convention is not agreed upon, it has been theorized by scholar Richard Neer that the Archaic Smile may be a denotation of status, since aristocrats were referred to as the Geleontes or the “smiling ones” in various cities around Greece.[29] Because this disappearance also coincides with a vanishing of funeral kouroi and korai (usually associated with aristocratic properties) around 480 BC,[30] if Neer’s theory is true, it would draw an affirming parallel between the changing features of sculpture and a society that is intent on striking out aristocratic connotations to create room for egalitarianism.

Figure 6. Kroisos Kouros Funerary Statue, Archaeological Museum of Athens.[31]

Emphasis on proportion is best displayed in the Doryphoros (“spear bearer”), an archetypal statue of Classical antiquity (Figure 7). Although the original was lost, it was extensively copied in the Roman period, resulting in well-preserved examples such as the marble copy from Pompeii that preserve the essential form of the work. It was sculpted by Polykleitos of Argos, who, alongside Phidias and Myron, was viewed as one of the most famous sculptors of the Classical age. The sculpture depicts a well-built athlete standing in contrapposto the instant he moves forward from a static pose. Alongside Polykleitos’ written Canon, a treatise detailing ideal proportions which only survives in fragments, the work embodies an aesthetic framework that remains foundational in the history of art.[32] Particularly, the Doryphoros, built with the principles in the Canon, demonstrates what Polykleitos considered to be the perfectly harmonious and balanced proportions of the human body in sculpted form. The scholars Richard Tobin and Gregory Leftwich have contributed significantly to this discussion, connecting the Canon with the Greek medical writer Galen from the 2nd century AD, who described the Doryphoros as the ideal visual representation of the Greeks’ search for beauty and harmony (Tobin 308; Leftwich 38).[33],[34] Polykleitos was concerned with the symmetria (proportions) of the constituent parts of the body, but he especially focused on the commensurability of the parts, or their ratios to one another. This includes comparisons such as that of finger to finger, the fingers to the hand, the forearm to the upper arm, and finally, the ratio of all the elements to each other. Furthermore, the Canon also proposed a “second, equally important system of proportions—a 1:1 ratio of opposites.”[35] This is visualized in the well-known series of balanced, naturalistic oppositions throughout Doryphoros, within its stance, axes, bent versus straight limbs, and the contrast between the left (movement), and the right (stationary) limbs, all synthesizing to create a dynamic equilibrium (isonomia). Although these intricate rules could be taken as simply motivated by classical realism and largely aesthetic in nature, it can be argued that they were also influenced by another elaborate structure in place during the Classical Age—the democratic system of Athens. Specifically, it is noteworthy how important balance and counterbalance is in the Canon, with no singular element excluded from consideration. This parallels the importance of balance in democratic ethos, also articulated with the word isonomia (“equality of political rights”).[36] Many practices were implemented to ensure this balance, including the judicial courts, the composition and creation of the Council of Five-Hundred, election by lot, single-year terms, and the distribution of power among boards of officials.[37] Democratic government itself is founded on the principles of fairness, collaboration, and equipoise. Thus, it can be said the overarching societal consideration of equality in Polykleitos’ time may have inspired his detailed method of representing the human body, and the Doryphoros may even be interpreted as a personification of a democratic ethos itself.

Figure 7. Doryphoros of Polykleitos, Roman Imperial period copy in the Naples National Archaeological Museum.[38]

Additionally, the trend in Classical sculpture towards rationality, simplicity, and discipline evident in pose (such as contrapposto), expression, disposition, and proportions can be summarized in the word sophrosyne. It is an ancient Greek concept broadly meaning an idyllic “excellence of character,” encompassing qualities such as self-restraint as well as soundness in speech and action of which there is no equivalent in other languages.[39] Although not a new term in the Classical Age, sophrosyne took on further importance after the ending of the Persian Wars from which the Greeks emerged victorious—particularly, it was credited as the very quality of the Greeks that made them superior, directly contrasting the term hubris that was used to label the Persians.[40] As stated by scholar Loukas Papadimitropoulos, “Hubris is clearly connected with excess and sometimes occurs in circumstances in which a mortal forgets the limitations of his status and seeks to compete with or even equal the gods; that is the reason why the gods are particularly interested in punishing hubristic attitudes.”[41] This characteristic attributed by the Greeks to the Persians is accentuated in many sources after the wars, including Aeschylus’ Persae, in which it is repeatedly stressed that the Greeks owed their victory to divine intervention.[42] Particularly, the Persians were painted as completely antithetical to the Greeks: tyrannical, hierarchical, and materialistic in nature.[43] These fundamental differences which the Greeks saw between themselves and the Persians may even have contributed to the solidifying of a clear Greek identity: simply, the Persians came to represent everything that was “non-Greek.” Thus, the echoing of values such as rationality, egalitarianism, and restraint in sculpture was not only targeting the excess of Greek aristocratic culture—it was also a rejection of everything “Persian,” a caricature that symbolized principles that were intolerable in a new Classical age society.

IV. Conclusion

In the fifth century, Greek sculptors achieved a means of depiction that imparted the vitality of life as well as a sense of coherence, harmony, and aesthetic endurance. Principles widely emulated throughout history, Classical Greek sculpture has had an extensive effect on the development of Western art. The pronounced developments that came to sculpture around the fifth century did not emerge by chance, but were rather instigated by the foundational changes in societal values that occurred contemporaneously. Through examining key principles and central pieces like the Parthenon’s architectural sculpture and the Doryphoros of Polykleitos, this paper concludes that the analogy between art and social context in the Classical Age can be summarized in two aspects of its sculpture: depicted subject matter and the comprehensive aesthetic features of sculpture itself.

Ultimately, the connection is not obscure to perceive. After all, art is one of the most important forms of expression. It translates and preserves cultural identity, beliefs, and sentiments—it is a mirror for the most fundamental of societal concepts, and therefore, can provide us with some of the most profound perspectives on the human condition.

Thus, when we look at a sculpture such as Doryphoros, it is understandable why we still find it so compelling today. Although wordless, it is able to fluidly communicate across more than two millennia, offering us an unique window into the fundamental values of Classical Greek society.

Millie Huang (College ’22) is a student at the University of Pennsylvania studying Neuroscience and Classical Studies.

Comments? Join the conversation on our Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn!

Footnotes

[1] Frances Pownall, “A case study in Isocrates: the expulsion of the Peisistratids,” Dialogues d’histoire ancienne, no. 8 (2013): 339–54, https://doi.org/10.3917/dha.hs80.0339.

[2] E R, “The Group of the Tyrannicides,” Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin 3, no. 4 (August 1905): 27–30.

[3] Charles H. Morgan, “The End of the Archaic Style,” Hesperia 38, no. 2 (April 1969): 205, https://doi.org/10.2307/147416.

[4] Andrew Stewart, “The Persian and Carthaginian Invasions of 480 B.C.E. and the Beginning of the Classical Style: Part 2, the Finds from Other Sites in Athens, Attica, Elsewhere in Greece, and on Sicily; Part 3, the Severe Style: Motivations and Meaning,” American Journal of Archaeology 112, no. 4 (2008): 608.

[5] Nigel Jonathan Spivey, Greek Sculpture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 137.

[6] Kritios, Deutsch: Tyrannenmörder-Gruppe Harmodios Und Aristogeiton, Römische Kopie Der Griechischen Frühklassischen Bronzeplastik, Im Archäologisches Nationalmuseum Neapel., Wikimedia Commons, accessed January 8, 2021, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harmodius_and_Aristogeiton.jpg

[7] Kenneth Clark, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts 2 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1972).

[8] Louis Magne, Athènes – Médiathèque de l’architecture et Du Patrimoine, Wikimedia Commons, accessed January 8, 2021,

[9] Rachel Kousser, “Destruction and Memory on the Athenian Acropolis,” The Art Bulletin 91, no. 3 (September 2009): 263.

[10] Russell Meiggs, “The Growth of Athenian Imperialism,” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 63 (November 1943): 21–34, https://doi.org/10.2307/627001.

[11] Kousser, “Destruction and Memory on the Athenian Acropolis,” 275.

[12] Russell Meiggs, “The Political Implications of the Parthenon,” Greece & Rome 10 (1963): 36–45.

[13] R~P~M, Parthenon, 1984, Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/5s2fB5.

[14] John Boardman, Greek Sculpture: The Classical Period: A Handbook, World of Art (New York, N.Y: Thames and Hudson, 1985).

[15] Christopher Ratté, “Athens: Recreating the Parthenon,” The Classical World 97, no. 1 (2003): 41–55, https://doi.org/10.2307/4352824.

[16] Joan B. Connelly, “Parthenon and Parthenoi: A Mythological Interpretation of the Parthenon Frieze,” American Journal of Archaeology 100, no. 1 (January 1996): 71, https://doi.org/10.2307/506297.

[17] Carole Raddato, South Metope XXVII, May 14, 2014, Photograph, May 14, 2014, Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/nqJy9w.

[18] Jenifer Neils, The Parthenon Frieze (Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

[19] Blaise Nagy, “Athenian Officials on the Parthenon Frieze,” American Journal of Archaeology 96, no. 1 (January 1992): 55–69, https://doi.org/10.2307/505758.

[20] Martin Robertson, “The Sculptures of the Parthenon,” Greece & Rome 10 (1963): 46–60.

[21] Pheidias, English: Peplos Scene. Block V (Fragment) from the East Frieze of the Parthenon, ca. 447–433 BC., Wikimedia Commons, accessed January 8, 2021, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Peplos_scene_BM_EV.JPG.

[22] Ratté, “Athens,” 50.

[23] Ratté, 50.

[24] Thucydides, “The History of the Peloponnesian War,” trans. Richard Crawley, May 1, 2009, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/7142/7142-h/7142-h.htm.

[25] Stewart, “The Persian and Carthaginian Invasions of 480 B.C.E. and the Beginning of the Classical Style: Part 2, the Finds from Other Sites in Athens, Attica, Elsewhere in Greece, and on Sicily; Part 3, the Severe Style: Motivations and Meaning,” 602.

[26] Kim Levin, “The Male Figure in Egyptian and Greek Sculpture of the Seventh and Sixth Centuries B. C.,” American Journal of Archaeology 68, no. 1 (January 1964): 13, https://doi.org/10.2307/501521.

[27] Whitney M. Davis, “Egypt, Samos, and the Archaic Style in Greek Sculpture,” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 67 (1981): 61–81, https://doi.org/10.2307/3856603.

[28] Francis Henry Taylor, “The Archaic Smile: A Commentary on the Arts in Times of Crisis,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 10, no. 8 (April 1952): 217–32, https://doi.org/10.2307/3258102.

[29] Richard T. Neer, Greek Art and Archaeology: A New History, c. 2500-c. 150 BCE (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2012), 156.

[30] Stewart, “The Persian and Carthaginian Invasions of 480 B.C.E. and the Beginning of the Classical Style: Part 2, the Finds from Other Sites in Athens, Attica, Elsewhere in Greece, and on Sicily; Part 3, the Severe Style: Motivations and Meaning,” 604.

[31] Paolo Villa, (Museo Archeologico Di Atene ) Kroisos Kouros. Marmo Pario. Trovato Ad Anavyssos. Statua Funeraria Ca 530 a.C. NAMA 3851, Con Gimp, February 18, 2020, February 18, 2020, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:02_2020_Grecia_photo_Paolo_Villa_FO190075_bis_(Museo_archeologico_di_Atene)_Kroisos_Kouros._Marmo_Pario._Trovato_ad_Anavyssos._Statua_funeraria_Ca_530_a.C._NAMA_3851,_con_gimp.jpg.

[32] Kenneth D. S. Lapatin et al., “Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition,” The Art Bulletin 79, no. 1 (March 1997): 148–56, https://doi.org/10.2307/3046234.

[33] Richard Tobin, “The Canon of Polykleitos,” American Journal of Archaeology 79, no. 4 (October 1975): 307–21, https://doi.org/10.2307/503064.

[34] Gregory V. Leftwich, “Polykleitos and Hippokratic Medicine,” in Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition., ed. Warren G. Moon (University of Wisconsin Press., 1995), 38 – 51.

[35] Leftwich, “Polykleitos and Hippokratic Medicine,” 38.

[36] Kurt A. Raaflaub, “Isonomia,” in The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, ed. Roger S Bagnall et al. (Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2012), https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah04152.

[37] Jeremy McInerney, Ancient Greece: A New History (New York, New York: Thames & Hudson, 2018), 202-205.

[38] Polykleitos, Doryphoros from Pompeii, sculpture in the round / Carrara marble, Height: 200 cm (78.7 in) dimensions QS:P2048,200U174728 (without plinth), Wikimedia Commons, accessed January 8, 2021, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Doryphoros_MAN_Napoli_Inv6011_n02.jpg.

[39] Helen F. North, “The Concept of Sophrosyne in Greek Literary Criticism,” Classical Philology 43, no. 1 (1948): 3.

[40] Stewart, “The Persian and Carthaginian Invasions of 480 B.C.E. and the Beginning of the Classical Style: Part 2, the Finds from Other Sites in Athens, Attica, Elsewhere in Greece, and on Sicily; Part 3, the Severe Style: Motivations and Meaning,” 605.

[41] Loukas Papadimitropoulos, “Xerxes’ ‘Hubris’ and Darius in Aeschylus’ ‘Persae,’” Mnemosyne 61, no. 3 (2008): 451.

[42] Aeschylus, “The Persians,” trans. Robert Potter, The Internet Classics Archive, 472AD, http://classics.mit.edu/Aeschylus/persians.html.

[43] Stewart, “The Persian and Carthaginian Invasions of 480 B.C.E. and the Beginning of the Classical Style: Part 2, the Finds from Other Sites in Athens, Attica, Elsewhere in Greece, and on Sicily; Part 3, the Severe Style: Motivations and Meaning,” 608.

References

Aeschylus. “The Persians.” Translated by Robert Potter. The Internet Classics Archive, 472AD. http://classics.mit.edu/Aeschylus/persians.html.

Boardman, John. Greek Sculpture: The Classical Period: A Handbook. World of Art. New York, N.Y: Thames and Hudson, 1985.

Clark, Kenneth. The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts 2. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1972.

Connelly, Joan B. “Parthenon and Parthenoi: A Mythological Interpretation of the Parthenon Frieze.” American Journal of Archaeology 100, no. 1 (January 1996): 53–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/506297.

Cook, R. M. “Origins of Greek Sculpture.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 87 (November 1967): 24–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/627804.

Davis, Whitney M. “Egypt, Samos, and the Archaic Style in Greek Sculpture.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 67 (1981): 61–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/3856603.

Kenneth D. S. Lapatin. “[Untitled] Review of Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition by Warren G. Moon.” Edited by Warren G. Moon, Guy P. R. Métraux, and Christine Mitchelle Havelock. The Art Bulletin 79, no. 1 (1997): 148–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/3046234.

Kousser, Rachel. “Destruction and Memory on the Athenian Acropolis.” The Art Bulletin 91, no. 3 (September 2009): 263–82.

Kritios. Deutsch: Tyrannenmörder-Gruppe Harmodios Und Aristogeiton, Römische Kopie Der Griechischen Frühklassischen Bronzeplastik, Im Archäologisches Nationalmuseum Neapel. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harmodius_and_Aristogeiton.jpg.

Levin, Kim. “The Male Figure in Egyptian and Greek Sculpture of the Seventh and Sixth Centuries B. C.” American Journal of Archaeology 68, no. 1 (January 1964): 13. https://doi.org/10.2307/501521.

Magne, Louis. Athènes – Médiathèque de l’architecture et Du Patrimoine. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ath%C3%A8nes_-_M%C3%A9diath%C3%A8que_de_l%27architecture_et_du_patrimoine_-_APMH00025749.jpg.

McInerney, Jeremy. Ancient Greece: A New History. New York, New York: Thames & Hudson, 2018.

Meiggs, Russell. “The Growth of Athenian Imperialism.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 63 (November 1943): 21–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/627001.

———. “The Political Implications of the Parthenon.” Greece & Rome 10 (1963): 36–45.

Morgan, Charles H. “The End of the Archaic Style.” Hesperia 38, no. 2 (April 1969): 205. https://doi.org/10.2307/147416.

Nagy, Blaise. “Athenian Officials on the Parthenon Frieze.” American Journal of Archaeology 96, no. 1 (January 1992): 55–69. https://doi.org/10.2307/505758.

Neer, Richard T. Greek Art and Archaeology: A New History, c. 2500-c. 150 BCE. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2012.

Neils, Jenifer. The Parthenon Frieze. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

North, Helen F. “The Concept of Sophrosyne in Greek Literary Criticism.” Classical Philology 43, no. 1 (1948): 1–17.

Papadimitropoulos, Loukas. “Xerxes’ ‘Hubris’ and Darius in Aeschylus’ ‘Persae.’” Mnemosyne 61, no. 3 (2008): 451–58.

Pheidias. English: Peplos Scene. Block V (Fragment) from the East Frieze of the Parthenon, ca. 447–433 BC. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Peplos_scene_BM_EV.JPG.

———. Métope Sud, XXVII, Centaure. August 2006. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elgin_Marbles9.jpg.

Polykleitos. Doryphoros from Pompeii. Sculpture in the round / Carrara marble, Height: 200 cm (78.7 in) dimensions QS:P2048,200U174728 (without plinth). Wikimedia Commons. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Doryphoros_MAN_Napoli_Inv6011_n02.jpg.

Pownall, Frances. “A case study in Isocrates: the expulsion of the Peisistratids.” Dialogues d’histoire ancienne, no. 8 (2013): 339–54. https://doi.org/10.3917/dha.hs80.0339.

R, E. “The Group of the Tyrannicides.” Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin 3, no. 4 (August 1905): 27–30.

R~P~M. Parthenon. 1984. Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/5s2fB5.

Raaflaub, Kurt A. “Isonomia.” In The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, edited by Roger S Bagnall, Kai Brodersen, Craige B Champion, Andrew Erskine, and Sabine R Huebner. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah04152.

Raddato, Carole. South Metope XXVII. May 14, 2014. Photograph. Flickr. https://flic.kr/p/nqJy9w.

Ratté, Christopher. “Athens: Recreating the Parthenon.” The Classical World 97, no. 1 (2003): 41–55. https://doi.org/10.2307/4352824.

Robertson, Martin. “The Sculptures of the Parthenon.” Greece & Rome 10 (1963): 46–60.

Spivey, Nigel Jonathan. Greek Sculpture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Stewart, Andrew. “The Persian and Carthaginian Invasions of 480 B.C.E. and the Beginning of the Classical Style: Part 2, the Finds from Other Sites in Athens, Attica, Elsewhere in Greece, and on Sicily; Part 3, the Severe Style: Motivations and Meaning.” American Journal of Archaeology 112, no. 4 (2008): 581–615.

Taylor, Francis Henry. “The Archaic Smile: A Commentary on the Arts in Times of Crisis.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 10, no. 8 (April 1952): 217–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3258102.

Thucydides. “The History of the Peloponnesian War.” Translated by Richard Crawley, May 1, 2009. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/7142/7142-h/7142-h.htm.

Tobin, Richard. “The Canon of Polykleitos.” American Journal of Archaeology 79, no. 4 (October 1975): 307–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/503064.

Villa, Paolo. (Museo Archeologico Di Atene ) Kroisos Kouros. Marmo Pario. Trovato Ad Anavyssos. Statua Funeraria Ca 530 a.C. NAMA 3851, Con Gimp. February 18, 2020. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:02_2020_Grecia_photo_Paolo_Villa_FO190075_bis_(Museo_archeologico_di_Atene)_Kroisos_Kouros._Marmo_Pario._Trovato_ad_Anavyssos._Statua_funeraria_Ca_530_a.C._NAMA_3851,_con_gimp.jpg.