A Fairytale

A very, very long time ago, Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin discovered the environment. Protests had become a fixture of the times, but Nelson envisioned something bigger, a protest for all and for all of earth. Earth Day. A movement that dwarfed any social movement that ever came before it was born. On April 22, 1970 hundreds, thousands, millions followed his call and celebrated the first Earth Day, launching the modern environmental movement. Or so the story goes….

A History

History is quite messy and things are always more complicated. Senator Gaylord Nelson certainly played a central role, but the reasons why Earth Day turned into the single largest political demonstration of the 1960s cannot be attributed to anyone person. Nor is this a particularly happy story.

Senator Nelson was hardly an activist and much less a radical. As historian Adam Rome illustrates in The Genius of Earth Day, “Nelson’s environmentalism was rooted in liberalism.” Inspired by the anti-war teach-ins, Nelson recognized the power of grassroots activism in advancing his particular concerns about the dangers to outdoors recreation and Nature write large. In September of 1969, he first aired his idea to organize a national teach-in that would draw attention to environmental issues, such as pollution, pressures on natural resources and the threats posed to habitats of fish, birds and other wildlife.

Nelson’s idea quickly gained traction but the process was hardly an organic one. With the help of younger aids, he established a teach-in office, hired staff, and launched a massive public relations campaign. In November the teach-in office incorporated as Environmental Teach-In, Inc. with a well stocked steering committee of politicians and luminaries. The young staff of activist veterans moved into a warehouse in Washington D.C., ditched the name of “teach-in” in favor of “Earth Day” and served as the hub that coordinated information flows and managed correspondence with local organizers at colleges and high schools across the nation.

Earth Day hit a nerve. In some places, Philadelphia among them, it ballooned into a week’s worth of events and activism. Initially imagined as an event primarily at universities across the country, interest in Earth Day spilled beyond college campuses. In Philadelphia, the main happenings stayed off campus and according to John Puckett, author of Becoming Penn, the events on and around Earth Day “had no impact on the larger campus.” The staff in D.C., overwhelmed by calls from across the country could barely keep up with the volume of events.

Harnessing the energy and experience of younger activist, Environmental Teach-In, Inc. never strayed far from either the political establishment or vested corporate interests, paving the way for the entry of young professionals into the environmentalist orbit. At the same time Nelson and his staff courted unions and labor representatives.

Initially, Nelson’s opposition to the Vietnam war struck him as merely coincidental. Even though others made these connections more readily, especially once antiwar activists focused on the use of Agent Orange, the toxicity of war remained at most a side note in Earth Day tracts and pamphlets. An amorphous concept of “pollution” instead took center stage that all too easily connected with an ominous rhetoric about blight, smog and garbage.

It is easy to see how Nelson was able to turn his quest for environmental change into a bipartisan issue. While environmentalism clearly learned from and mobilized strategies of student revolutionaries, anti-war, civil rights and black power activists and maintained strong affinities with platforms and representatives of the New Left, a focus on nature and wilderness on the one hand and cleanliness and orderliness on the other provided numerous points of overlap with middle of the road American values and conservative interests.

As predominantly white activists found their new roles as earth saviors and population control advocates, concerns over garbage, pollution and filth provided an opportunity to bridge over seemingly incommensurate political divides, making environmentalism a form of activism that appealed to a broad, often apolitical mass and was yet compatible with a hippie-esque lifestyle, a critique of capitalism and self-empowering individualism.

Appealing to universals that either glossed over or blatantly ignored the pervasive inequalities that ripped through America and divided the world, arguments for the salvation of Earth aspired to be above politics. The celebratory crowds that gathered in Philadelphia and across the country on April 22, 1970 delivered on that image.

But as philosopher Charles Mills so pointedly illustrates in The Racial Contract and other writings, the universals deployed by the white majority were themselves a product of the history of white supremacy. “Blacks” Mills argues “are not part of the universal ‘we’” environmentalists invoked when expressing their concerns about waste and pollution. Instead there was a sense among white environmentalists, Mills suggests, according to which “blacks themselves are an environmental problem, which ‘we’ full humans (that is the white population) have to deal with.”

It is thus no surprise that minorities, particularly black Americans, were deeply suspicious of environmentalists’s claims that their universalism by default aligned with and in fact represented the interests of black communities and other minorities. In the eyes of black politicians and activists, environmentalists diverted attention from an unfinished struggle for racial equality and justice.

Environmentalism: Roots and Legacies

The history of environmentalism is almost always told as a triumphal story. A variation on David versus Goliath in which grassroots activists forced government and industry representatives to consider the earth as a stakeholder. And yet, modern environmentalism pushed environmental issues into the mainstream. That story is very much true. But it is is only one part of a bigger story.

Questions about human relations to nature, worries about the loss of wilderness, recognition of the destructive impact of human civilization on the environment were not new, they in fact preceded the sixties and the proclamation of the first Earth Day by centuries if not millennia. But somehow the experiences brought activists and environmentally conscious citizens together around and beyond the first Earth Day were different. Environmentalism offered wholesome activism that, as much as it owed to the radicalism of the sixties, tapped into the populist desire to bridge divisions and affirm the shared humanity of all.

The shift in popular awareness has often been attributed to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which had inspired Americans to think about the pervasiveness of toxins and pollution. Carson, a marine biologist, who originally published her intervention in a serialized fashion in The New Yorker, resonated with suburban, white middle class, educated Americans whose kids grew up with “duck and cover drills” and the threat of nuclear annihilation.

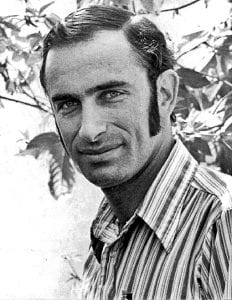

But the urgency that environmentalists experienced owed at least as much to arguments about the imminent dangers of overpopulation supposedly threatening the health of the planet. As protests exploded across the United States, student revolutionaries clashed with authorities in Paris, Prague and Mexico City, and sanitation workers laid waste to American cities in 1968, Paul Ehrlich, a young biologist at Stanford University, published The Population Bomb. warning of unsustainable overpopulation. Describing how he came to know the “feel of overpopulation” on a family trip to India while traveling by taxi through Delhi, Ehrlich becomes acutely aware of “people. People eating, people washing, people sleeping. People visiting, arguing, and screaming. People thrusting their hands through the taxi window, begging. People defecating and urinating. People clinging to buses. People herding animals. People, people, people, people.”

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20701670

What really seemed to have unsettled Ehrlich was the sight of poor people of color. People who offended his western sense of order, decorum, and privacy. Ehrlich’s subsequent musings on the “population problem” invoked eugenicist arguments of an earlier time. Ehrlich’s proposed “birth rate solution” contemplated such radical measures as adding sterilants to the water supply and implementing taxation to de-incentivize and punish what he deemed to be “irresponsible reproduction” in order to avoid the otherwise “inevitably” unfolding “death rate solution.”

It is not surprising that Ehrlich’s book resonated with large segments of the population in the aftermath of racial demonstrations, civil disturbances and the massively successful garbage strikes by predominantly black sanitation workers in cities across the country in 1967, 1968 and 1969. It is equally unsurprising that a focus on eco-systems, pollution, filth, limited resources and overpopulation by overwhelmingly white environmentalists was profoundly threatening to African Americans and other underprivileged communities.

Huey Newton, the founder of the Black Panthers put it bluntly: “Human beings are the component left out of the survival equation by the environmentalists except in generalized ‘underdeveloped’ nation statistics, and as objects of blame for the whole mess in the industrialized countries and, of course, as suicidal breeders in the colonies.”

Turning toward the earth and away from increasingly frustrated, thwarted and occasionally militant activists for racial and social justice, Earth Day managed to make environmentalism a mass movement that crossed party lines and bridged generational divides, bringing progressive and conservationist pressures to bear on government and industry representatives to “give Earth a chance.”

It is not the first time that America’s unity was won at the expense of its most vulnerable populations.

It seems that now, student activists at Penn in 2020 are not replicating those mistakes. Acutely aware of the disproportionate burden that environmental degradation places on underprivileged communities and communities of color, they have made environmental justice a primary focus in their efforts to address the climate emergency.

References

Allitt, Patrick. Climate of Crisis: America in the Age of Environmentalism. New York: Penguin, 2015.

Brick, Howard. Radicals in America: The U.S. Left Since the Second World War Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. Boston: Hougton Mifflin, 1962.

Ehrlich, Paul. The Population Bomb: Population Control or Race to Oblivion. New York: Ballantine Books, 1968.

Mills, Charles W. “Black Trash” in Faces of Environmental Racism: Confronting Issues of Global Justice. 2nd ed. Laura Westra and Bill E. Lawson. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001: 73-91.

Mills, Charles, W. The Racial Contract. New York: Cornell University Press, 1997.

Montrie, Chad. The Myth of Silent Spring. Rethinking the Origins of American Environmentalism. Oakland: University of California Press, 2018.

Puckett, John L. and Mark Frazier Lloyd. Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University, 1950-2000. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015

Robertson, Thomas. The Malthusian Moment: Global Population Growth and the Birth of American Environmentalism. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2012.

Rome, Adam. The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation. New York, Hill and Wang, 2013.

Washington, Sylvia Hood. “Ball of Confusion: Public Health, African Americans and Earth Day 1970” in Natural Protest: Essays on the History of American Environmentalism edited by Michael Egan and Jeff Crane. New York: Routledge, 2009: 205-222