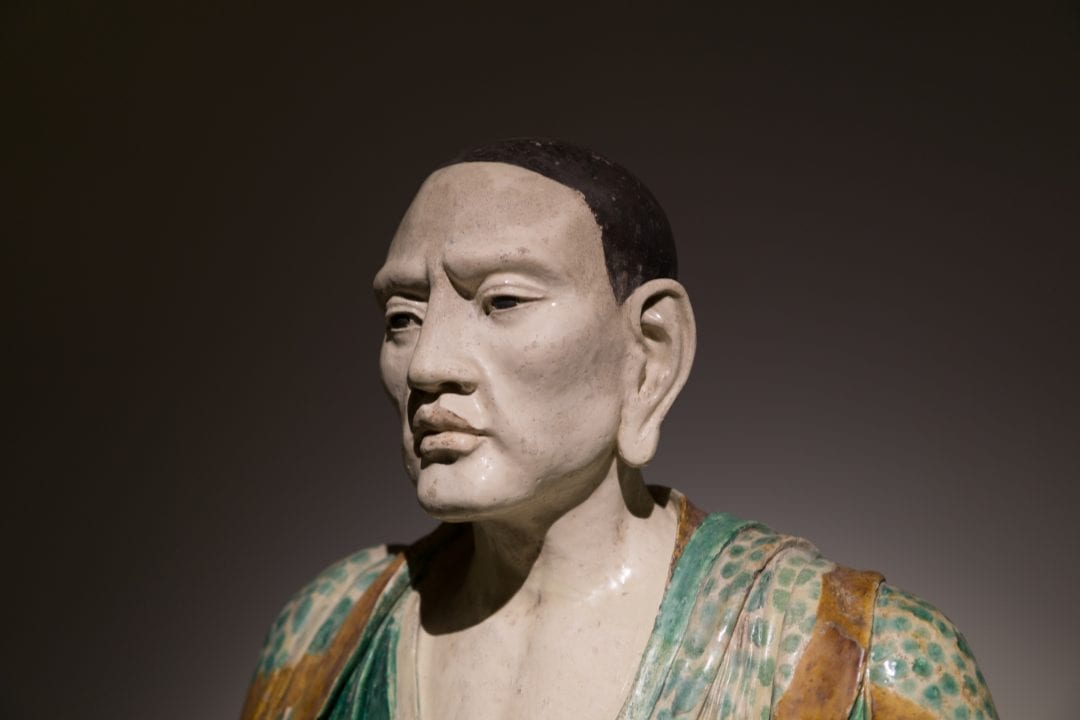

This tri-color glazed sculpture of an arhat (Luohan) is displayed in the gallery with other medieval Buddhist sculptures at the Musée Guimet in Paris. In 1912, it was discovered in a cave west of Yi County as a part of a set of arhat sculptures. Today, this set is primarily housed in museums in America and Europe that are renowned for their collections of East Asian art, including the Penn Museum. Although there is an ongoing discussion on its year of production, this set was commonly believed to be produced in the twelfth or thirteenth centuries.

The “discovery” and subsequent dispersal of this set of sculptures can be seen as part of a broader trend of collecting Chinese art in the West during the 19th and early 20th centuries. According to the memoir of the German art dealer specializing in Asian art, Friedrich Perzyński, he saw a sculpture of an arhat in his residence in Beijing in 1912. Later, he went to Yi County to search for the sculptures in the style he had seen earlier. However, he did not find any sculptures in the caves when he arrived. Perzyński later purchased a number of the sculptures and shipped them overseas. It is said that three of the sculptures were destroyed beyond repair during their transportation down from the mountains by local villagers. While in that same year, the last imperial dynasty of China ended as its six-year-old emperor, Puyi, proclaimed his abdication.

Through the hands of various dealers, this set of sculptures found its way into collections scattered across the West. In 1912, the Museum of Fine Art in Boston purchased a sculpture from the Japanese dealer Yamanaka & Co. The following year, Perzyński exhibited two sculptures at the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin. The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired one of them, while the other was purchased by Harry Fuld and gifted to the Museum für Asiatische Kunst in Berlin. This sculpture was later destroyed during World War II, but a fragment of a similar sculpture was recently discovered in the storage room at the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg. The British Museum procured another piece from the dealer, S. M. Franck & Son. In 1914, the director of the Royal Ontario Museum, Charles Currelly, visited the British Museum and also acquired one from S. M. Franck & Son. That same year, Edgar Worch, another German art dealer, exhibited one of the sculptures at the Musée Cernuschi in Paris, a museum still recognized today for its collection of East Asian art. One sculpture now resides prominently in the center of the Chinese Rotunda at the Penn Museum, having been procured from the renowned Paris-based dealer, C. T. Loo, whose historic residence, the Paris Pagoda, still stands today. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art added another piece to its collection from C. T. Loo in 1933. In 1921, the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired another sculpture of this group from the Shanghai-based dealer, Laiyuan & Company. In addition to these pieces, one was collected by a private collector in Japan, and a fragment resides at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Lastly, a fragment believed to belong to this set was unearthed near the original site in Yi County in 1996 and is now preserved by the local cultural heritage authority.

This arhat at Musée Guimet is believed to have been in a private collection in France and was later donated to Musée Guimet by Tsui Tsin-tong, a collector from Hong Kong. It was not shown to the public until the Musée Guimet completed its renovation in 2001.

The map below denotes the present-day locations of the Yi County arhats. Institutions that have collected these sculptures are marked with red pins, while the original site of these arhats, along with the location of one fragment, is indicated by a blue pin.

Today, each sculpture from this set serves as a testament to the institutions that host them, underlining their significant contributions to the collection of East Asian art in the Western hemisphere. They stand as tangible demonstrations of the exquisite craftsmanship characteristic of the period, reflecting the highly realistic achievable features. The dissemination of this set of arhats across Western museums in the twentieth century is emblematic of the broader transmission and appreciation of Chinese art outside its homeland. As enduring artifacts, these pieces continue to facilitate a deeper understanding of the history and culture of medieval China, playing a pivotal role in the scholarly discourse and public engagement in today’s world.

Suggested Readings:

Eileen Hsiang-ling Hsu, “Monks in glaze : patronage, kiln origin, and iconography of the Yixian Luohans,” Brill, Leiden, 2017.

Smithies, Richard, “A Luohan from Yizhou in the University of Pennsylvania Museum,” Orientations 32, no.2, pp. 51–56