Statements by themselves aren’t that interesting; let’s see how to combine them.

“not”

A writing teacher once told me the best way to clean up your writing is to eliminate as many adverbs and adjectives as possible. But one very important adverb–which changes the meaning of anything it touches–is the word not. Let’s formalize this.

Definition. Given a statement  , the statement

, the statement  (read It is not the case that

(read It is not the case that  or the abbreviated version not

or the abbreviated version not  is true exactly when

is true exactly when  is false.

is false.

Note that if  is a statement, it’s either true or false; in either case, we know what truth value

is a statement, it’s either true or false; in either case, we know what truth value  has. So

has. So  is by definition a statement. Also note the word exactly, which modifies when.

is by definition a statement. Also note the word exactly, which modifies when.

Proposition 1.  is true exactly when

is true exactly when  is true.

is true.

Proof. There are only two kinds of statements  , namely true and false.

, namely true and false.

If  is false, then

is false, then  is true (this is the definition of

is true (this is the definition of  ). But the only (that’s the exactly in the definition of

). But the only (that’s the exactly in the definition of  ) way for

) way for  to be true would be if

to be true would be if  were false; since

were false; since  is true, we know

is true, we know  is false. So in this situation,

is false. So in this situation,  and

and  are both false.

are both false.

If  is true, then

is true, then  is false (remember,

is false (remember,  is only true when

is only true when  is false). So

is false). So  is true. So here again,

is true. So here again,  and

and  agree with one another.

agree with one another.

In both cases, we’ve seen that  and

and  agree. Thus when

agree. Thus when  is true,

is true,  is true; and this is the only way for

is true; and this is the only way for  to be true.

to be true.  .

.

Notice that  is a different formula from

is a different formula from  . For example, if

. For example, if  is I wear a plaid shirt every day, then

is I wear a plaid shirt every day, then

is It is not the case that I wear a plaid shirt every day and

is It is not the case that I wear a plaid shirt every day and

is It is not the case that it is not the case that I wear a plaid shirt every day.

is It is not the case that it is not the case that I wear a plaid shirt every day.

But of course  and

and  are the same insofar as truth goes. One might say they mean the same thing.

are the same insofar as truth goes. One might say they mean the same thing.

To make better formal sense of the distinction between being the same statement and merely being statements that mean the same thing, we need the following definition:

Definition. A propositional formula or propositional form is a string of logical connectives and variables, so that when each of the variables is substituted with a statement, the result is a statement.

For example,  is a propositional formula because if we supply a statement in place of

is a propositional formula because if we supply a statement in place of  , we obtain a statement.

, we obtain a statement.

Definition. Two propositional forms are equivalent if, whenever we substitute the same statements in for their variables, we obtain statements with the same truth values.

Armed with this definition, we can rewrite Proposition 1 in a different way:

Restatement of Proposition 1.  and

and  are equivalent.

are equivalent.

denials, useful and otherwise

Definition. A formula equivalent to  is called a denial of

is called a denial of  . If we plug a statement in to the variable

. If we plug a statement in to the variable  , we obtain a denial of that statement.

, we obtain a denial of that statement.

E.g.  and

and  are denials of

are denials of  .

.  is a denial of

is a denial of  .

.

E.g. A denial of Andrew Cooper is from Texas is It is not the case that Andrew Cooper is from Texas.

Another denial is Andrew Cooper is not from Texas.

Another denial is Andrew Cooper is either from someplace other than Texas, or he is not from anyplace in particular, a drifter if you will, rootless, without a home.

These examples show that there are many different denials of any given formula or statement.

One question I want you to ask, and to keep asking is: is a given formulation of a statement useful to me? Utility is in the eye of the beholder, so I won’t give you a formal definition of what I mean when I say useful denial. But I’ll say this: merely attaching It is not the case that… to the beginning of a statement probably will not yield any insight.

You might be asking yourself: why should I expect that formulating a denial would yield any insight, anyway? Here’s why, and it’s a very important less in thinking that I hope you take away from this course into the rest of your life beyond mathematics. Statements are, by definition, either true or false (and not both). So, when we are faced with a statement we don’t understand (or wish to understand better, or wish to prove), we usually ask questions like

- What does this statement mean?

- If this statement were true, what else would be true?

- When have I encountered similar (or just similar-looking) statements in the past?

These are great questions, but they don’t always get us where we need to go. Sometimes they can even lead us astray. Since we know that the statement in question is either true or false, we could as well ask about it:

- What would it mean for this statement to be false?

That is, we could formulate a denial of the statement. If we articulate all the ways the statement could be false, then we have also articulated what it means for the statement to be true: that’s just everything not on our list.

I call this method what-if-not thinking, and we’re going to use it a lot. But it depends, critically, on being able to formulate denials precisely and accurately. (Don’t worry, we’ll develop lots of practice.)

truth tables

Definitions like that of  are kind of hard to read, so let’s record them symbolically. We can think of

are kind of hard to read, so let’s record them symbolically. We can think of  as being like a function: you tell it the truth value of

as being like a function: you tell it the truth value of  , and it tells you the truth value of

, and it tells you the truth value of  . So, just like you first did in some long-ago algebra class, we can record the values in a table. We call such a table a truth table. The truth table for

. So, just like you first did in some long-ago algebra class, we can record the values in a table. We call such a table a truth table. The truth table for  looks like this:

looks like this:

|

|

| T |

F |

| F |

T |

We can make a truth table for any formula; here’s the truth table for  :

:

|

|

| T |

T |

| F |

F |

Observe that we always list the input values (the first column) in the same order.

It’s pretty clear that Two formulae are equivalent if the output columns of their truth tables are the same.

“and”

not was nice, but it only acts on one statement or formula. (We call such operations unary, from the Latin unus “one”.) Let’s get some binary operations: operations which combine two statements or formulae. We’ll start with the word and.

Before reading any further, make sure you’ve done the pre-meeting exercise: read the dictionary.com entry on the word and and see if it would help you understand what the word meant, if you didn’t already know. Try this definition also.

Instead of giving a wordy definition, I’ll just give the truth table for “and”. The symbol we use is  . Since there are two inputs, each of which has two possible truth values, there are four possible inputs:

. Since there are two inputs, each of which has two possible truth values, there are four possible inputs:

|

|

|

|

| T |

T |

T |

1 |

| T |

F |

F |

2 |

| F |

T |

F |

3 |

| F |

F |

F |

4 |

Because we’re going to use this table rather than just look at it, I’ve given numbers to the rows.

Let’s play around a bit with this. What’s  ? We’ll make a truth table. In order to compare it with the truth table for

? We’ll make a truth table. In order to compare it with the truth table for  , we need to list the inputs in the same order.

, we need to list the inputs in the same order.

|

|

|

|

| T |

T |

T |

1 |

| T |

F |

F |

3 |

| F |

T |

F |

2 |

| F |

F |

F |

4 |

Look carefully at the row labels. In order to populate row 2 of the  table, we have to look at row 3 of the

table, we have to look at row 3 of the  table — this row is the “FALSE and TRUE” row.

table — this row is the “FALSE and TRUE” row.

We can conclude from this truth table that

Proposition.  and

and  are equivalent formulae.

are equivalent formulae.

Or, somewhat more pithily, we say

Restatement of Proposition.  is commutative.

is commutative.

While this proposition may not surprise you, it does indicate a slight difference from the ordinary-English word and.

Let’s try something else out, too: what about  ? This time we’re have three inputs, each of which has two possible truth values, for a total of

? This time we’re have three inputs, each of which has two possible truth values, for a total of  possible input truth values:

possible input truth values:

|

|

|

|

|

|

| T |

T |

T |

T |

T |

1 |

| F |

F |

2 |

| F |

T |

F |

F |

3 |

| F |

F |

4 |

| F |

T |

T |

F |

F |

3 |

| F |

F |

4 |

| F |

T |

F |

F |

3 |

| F |

F |

4 |

Here I’ve done two tricks: first, instead of writing so many Ts and Fs, I combined some rows in the  and

and  columns to make the table easier to read. Second, I wrote down the intermediate step of computing

columns to make the table easier to read. Second, I wrote down the intermediate step of computing  as a separate column. The last column records which row of the truth table for

as a separate column. The last column records which row of the truth table for  I used to go combine the values in the third and fourth columns to get the truth value in the last column.

I used to go combine the values in the third and fourth columns to get the truth value in the last column.

Exercise. Make a truth table for  .

.

Proposition.  is equivalent to

is equivalent to  .

.

The pithy way to say this is

Restatement of Proposition.  is associative.

is associative.

Finally, let’s do two truth table computations with  and

and  :

:

Exercise. Make truth tables for  and

and  . Before beginning this, think hard about how many rows and how many columns your truth table will require. Then see if you notice anything interesting.

. Before beginning this, think hard about how many rows and how many columns your truth table will require. Then see if you notice anything interesting.

Tautologies and Contradictions

The result of the previous exercise will leave us with the need for the following definition:

Definition. A formula which always has a truth value of T, no matter what inputs it takes, is called a tautology. A formula which always has a truth value of F, no matter what inputs it takes, is called a contradiction.

If we’re thinking of propositional formulae as functions, then tautologies and contradictions are the constants. (There are only two constant functions, because statements can only be true or false (and not both).)

The philosopher’s version of this definition goes something like A tautology is a sentence that is true in virtue of its form. and A contradiction is a sentence that is false in virtue of its form., the point being that neither a tautology nor a contradiction can contain much in the way of meaningful content, because its form gets in the way. But that’s all a bit above our heads.

Shades of Meaning

Here’s a shocking claim:

and and but mean the same thing.

What do I mean by this? Consider the two statements:

- I have a dog and he weighs twelve pounds.

- I have a dog but he weighs twelve pounds.

In terms of the facts on the ground, what do we know in situation 1? That I have a dog. That the dog weighs twelve pounds. What do we know if situation 2? Exactly the same information!

So what’s different? Presumably, if I’m saying statement 2, it’s because I’m vaguely embarrassed to have such a small dog (sorry, Mugzy). That is, the difference between and and but lies in how the speaker feels about the circumstances. And because that’s not something that can be true or false, our logical framework just doesn’t care about it.

You might think this is a bug, but I see it as a feature. (Perhaps better to say: you might see this as a bug, and I see it as a feature.) It will allow us to subtly influence our reader’s perception — and our own perception — in ways that may make our written proofs clearer and easier to understand.

A neat thinking trick you can deploy to help make sure you aren’t being unduly influenced (say, when you’re watching talking heads): every time someone says but, just repeat what they said with an and instead. And make sure you don’t use but when you mean and.

and

, the proposition

(read

or

) has truth value as given below:

is commutative.

is associative.

interacts with

. Try your hand at proving the following, using truth tables:

and

distribute over one another; that is:

is equivalent to

(this is

distributing over

.)

is equivalent to

(this is

distributing over

.)

is equivalent to

is equivalent to

. We’ll use the symbol

to mean is equivalent to.

by De Morgan’s Law 2

by De Morgan’s Law 1

says

says

. Above we applied de Morgan’s Law first; but since we know that

and

distribute over one another, we could equally well have derived

by de Morgan’s Law 1

by de Morgan’s Law 2

and

will become so second nature to you that will begin applying them without thinking about it. But here we’ve spelled everything out.

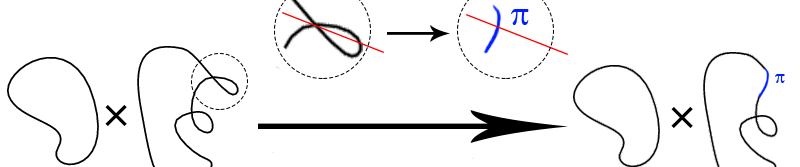

With the help of artist Viktor Vasnetsov, we form a bijection like

With the help of artist Viktor Vasnetsov, we form a bijection like