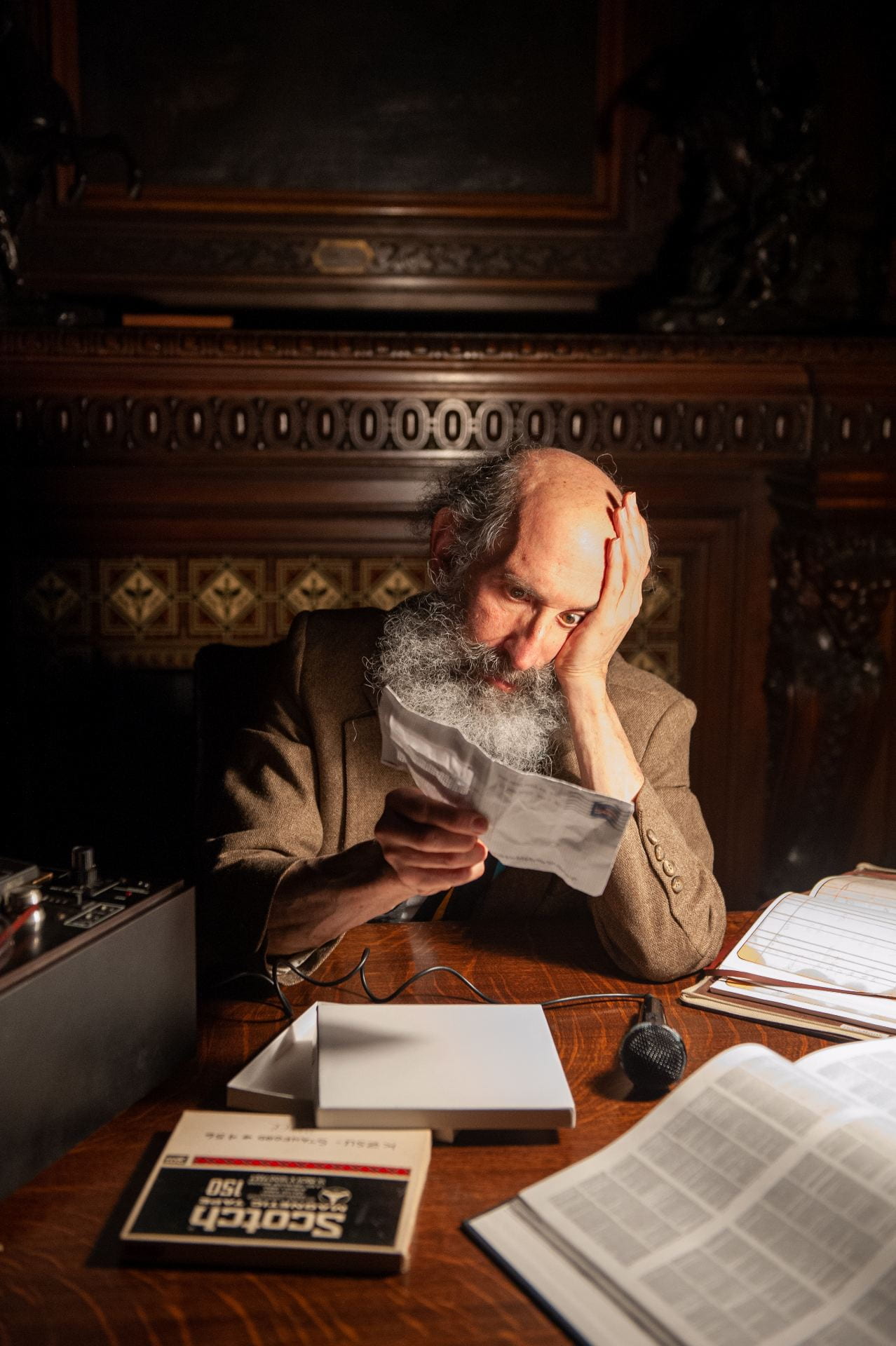

On February 22, 2022, his 69th birthday, Mazer played Krapp in a one-night-only performance of Krapp’s Last Tape by Samuel Beckett, directed by David O’Connor, in the Lea Library at the University of Pennsylvania, having recorded the tape (which Krapp had recorded on his 39th birthday, and which he listens to on his 69th birthday) thirty years earlier, on his 39th birthday, February 22, 1992.

ACTOR’S NOTE

(Please don’t read this until after the performance.)

At first, it was just a gimmick. Sure, it was egocentric and narcissistic, but a gimmick nonetheless. On every birthday, Krapp makes a tape, a record of events and insights from the preceding year. In the play, Krapp, on his 69th birthday, listens to the tape he recorded on his 39th birthday 30 years before, and then records his latest, perhaps his last, birthday tape. It was 1992. My 39th birthday was approaching. If I were to record the content of Krapp’s 39th birthday tape on my own 39th birthday, then, 30 years later, if I were still alive and healthy, if I could remember where I had stored the tape, if the tape had not deteriorated beyond audibility, and if circumstances allowed, I could perform Beckett’s play on my own 69th birthday, with my own 39-year-old voice coming out of the tape recorder. It wouldn’t matter whether my talents were up to the demanding role; the gimmick would be enough … enough justification for doing it, and quite possibly enough justification for someone to see it.

What I didn’t know—how could I have? How could anyone have?—was what my life would be like 30 years in the future. I couldn’t have anticipated the crises—political, environmental, medical—that the world endured and is still enduring. And, above all, I couldn’t have known how the changes in my life paralleled the changes that Krapp bears witness to in his. No, I don’t share his addictions, either to alcohol or to bananas. Unlike Krapp, I don’t live alone (as Beckett depicts him), nor do I secretly reside in a university library, hiding from the users and the staff and emerging only after closing time (as David O’Connor and I have reconceived him). True, my last book sold no better than his. I’m not myopic, but I do have extreme double vision. And, in case you were wondering, the answer to your question as to whether or not I share Krapp’s chronic constipation is, “None of your business.” More significantly, I couldn’t have known at the time that the person I had been dating for only a few months when I recorded the tape would become my life partner, nor that we would add a miraculous child to our family; and so, unlike Krapp, I have not had to say farewell to love.

But when I, like Krapp, listen to the voice of the person I was 30 years ago, I experience something not at all unlike what the character does. Like Krapp, I sense that the person on the tape is me and at the same time is not me. I want, I value, I remember different things than I thought I would. This year—the year I retire after 43 years of teaching at Penn, a year in which I am more keenly aware of the advancing symptoms of a degenerative neurological condition—I am unusually alert to what I am leaving behind and what I have lost. But I am also aware of what is still important to me and what isn’t, and to the ways that I am proactively realigning my professional activities and redirecting my creative energies.

The first plays I directed at Penn were two one-act plays by Beckett. How fitting that the last theatre piece I help give voice to at Penn is another Beckett play. And how ironic that Beckett—the apostle of going on even when life ceases to have meaning—has made me keenly aware of what gives me joy, and what I still have to live for.