Today, much is made of “cancel culture,” or economically punishing those whose statements, ideas, and behaviors violate the values of various groups. Canceling can include calls for firing individuals who take objectionable stances; boycotting businesses that behave similarly; or, in the case of celebrities, steering clear of their performances. “Call out culture” also condemns offensive language and behaviors but is more often associated with pressure for apologies and reform than economic punishment. Both could be seen in Salem, Massachusetts on the eve of the American Revolution.

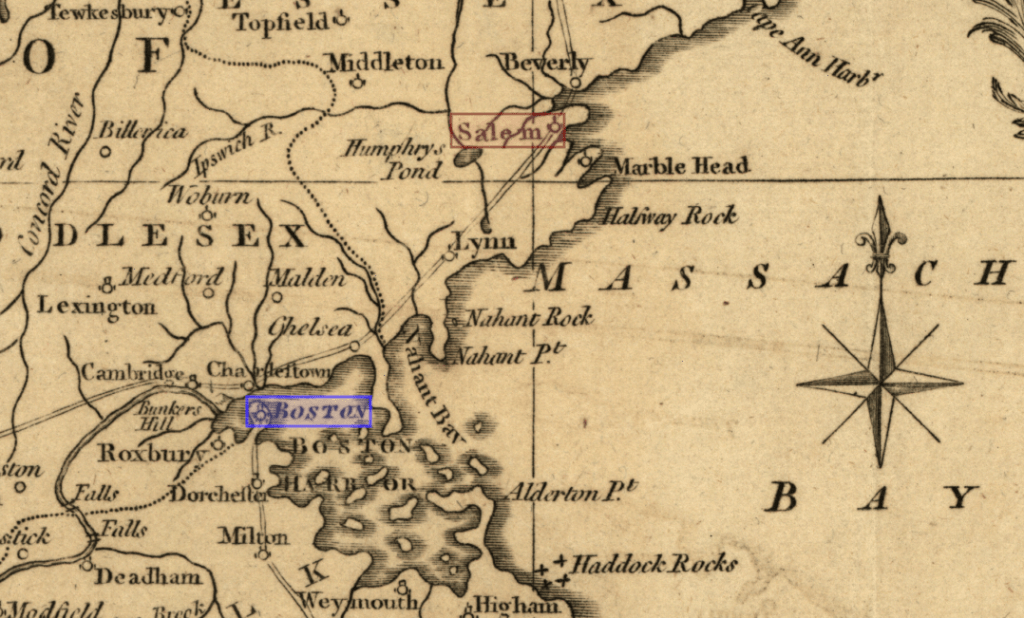

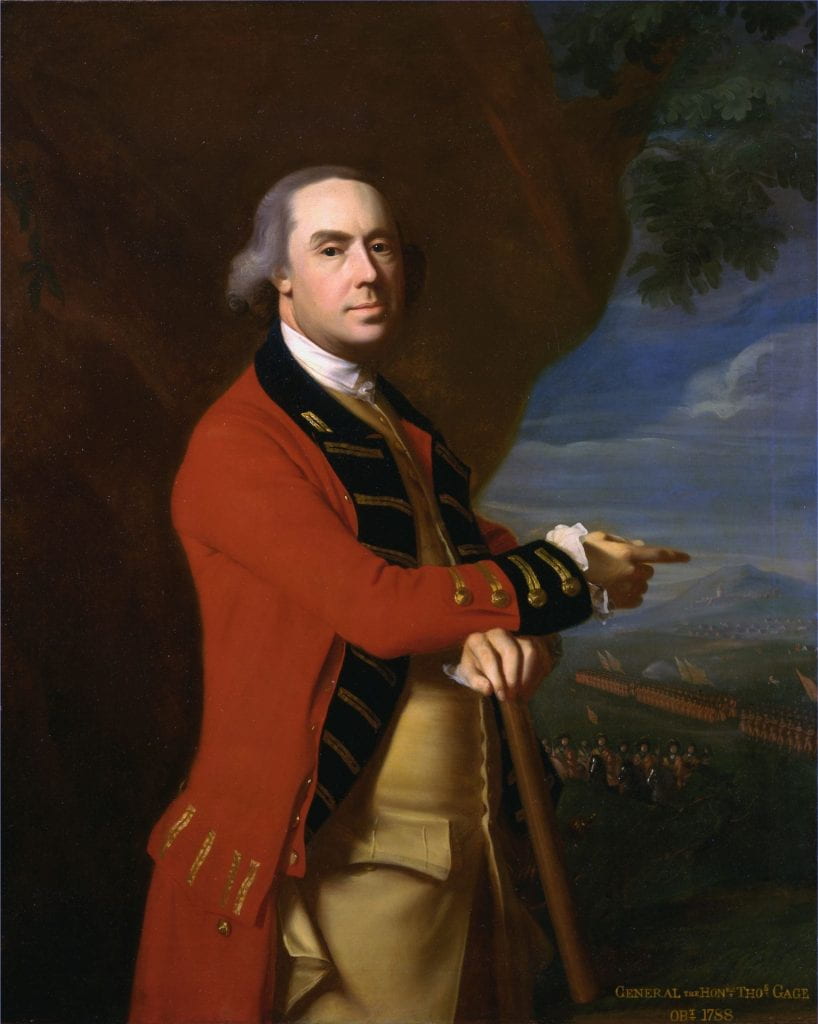

Following the Boston Tea Party in December 1773, Parliament passed the Boston Port Act, which closed that city’s harbor. This led General Thomas Gage, recently appointed Royal Governor of the Bay colony, to move the seat of government to the port of Salem. When Gage arrived in that town, he was greeted by two addresses. The signers of the first address embraced the new governor but also seemed to accept the Port Act’s closure of Boston Harbor, based in part on the assumption that the closure would send business to Salem. The second address called for the repeal of the Port Act. Its signers also rallied against any acceptance of Boston’s closure, stating, “By shutting up the port of Boston some imagine that the course of trade might be turned hither, and to our benefit;” but the address notes that such action injured every community in the province. More importantly the second address states, “We must be dead to every idea of justice, lost to all the feelings of humanity, could we indulge one thought to seize on wealth and raise our fortunes on the ruin of our suffering neighbors.” In short, the signers of the second address to Gage not only demanded the repeal of the Port Act, they also called out the signers of the first address for accepting the law.1

About two months after receiving the second address, Gage left Salem. Before and after his departure, something akin to modern cancel culture was prominent in the area. The people of Massachusetts were angered by the Port Bill, but they were equally upset by the Massachusetts Government Act, a companion piece to the former law. The Government Act was seen as intolerable because it made the Governor’s Council, which had been chosen by the popularly elected Assembly, subject to royal appointment; it stripped the Council of its power to approve judges and sheriffs; it awarded royally appointed sheriffs the power to select juries; and it allowed towns only one annual meeting to elect local officials unless the governor approved other assemblages. The towns of Essex County, like those throughout Massachusetts, summoned county conventions to confront this law.

When Salem’s committee of correspondence called a meeting to choose delegates to the Essex County Convention, the members did not seek Gage’s approval. The general claimed the meeting thus violated the Government Act and ordered the meeting to disband. Gage also ordered the arrest of the committee members who summoned the meeting and he required that each post a bond of £100. The town ignored Gage’s demand, met, and chose delegates to the convention. Two committee members turned themselves in and posted bond but the others, led by Richard Derby Jr., refused and informed Gage that even if the bond was reduced to “the ninetieth part of a farthing … they would not give it,” and if he had them arrested, “he must abide by the consequences.” With approximately three thousand armed militia in the area, Gage dropped the matter and within days returned to Boston.2

The extralegal Essex Convention met and imposed severe economic penalties on those supporting the Massachusetts Government Act. One Convention resolution stated, “all civil officers … as well as private persons who shall dare to conduct [business] in conformity to the aforementioned act … will be considered by this county as its unnatural malignant enemies [and] while they persist … are unfit for civil society; their lands ought not be tilled by the labor of an American, nor their families supplied with his clothing or food.”3

Cancel culture did not end with the Essex Convention. Salemites appear to have spontaneously directed other less stringent economic sanctions on those suspected of supporting the English position. This can be seen in the issue of the Essex Gazette that contained the Commission’s resolutions. The paper published apologies by William Vans and Samuel Flagg, two Salem merchants who signed the address to Gage and another to Hutchinson. These apologies parallel those that come from today’s public figures who have been called out or canceled. Vans declared in an advertisement “That I do from my Heart abhor the right of taxing America … as also the Boston Port-Bill, and other late Acts abridging the rights of this province, and I do promise to join my Bretheren in America in the most effectual constitutional Methods to oppose and frustrate those laws.” Vans asked his neighbors to “treat me again with their usual Friendship, Benevolence and Favour.”

The word “Favour” is important here; it refers to the favor of their patronage at his shop. Vans also took concrete action to demonstrate his commitment to the American cause. He stated that “For the encouragement of American Manufactures,” he would exchange American homespun cloth “for any goods of his shop.” Flagg’s case unfolded similarly. Flagg stated in an advertisement that, although he continued to sell English goods, he would not import any more. The next week Flagg published an apology for signing the address to Hutchinson. He explained that he was sorry “not simply because I am injured in my business, but because nothing can compensate for the loss of the good opinion of my countrymen.” Shortly thereafter a controversy arose when William Browne, despite colonial pressure, refused to resign as colonel of the Essex Militia. Flagg, who held a commission in the unit, joined the other officers and resigned his position, clearing the way for the election of militia officers. The actions of Vans and Flagg, an apology followed by concrete action to support the colonial cause, became a sort of template former royalists followed to secure acceptance by their neighbors. And acceptance came to both men. Flagg was elected an officer in the reformed militia, and Vans was voted town treasurer in 1778.4

Today calling out or canceling individuals or groups for objectionable behaviors often occurs on social media but such actions are not the product of the digital age. They existed in early times, when communities were small and word spread rapidly from person to person on the streets and in local gatherings. While some today regard cancel culture as an assault on freedom of speech and thought, Revolutionary Americans refused to enrich and empower those whose words and actions threatened their property, their liberty, and their dignity.

Richard Morris (he/him) is Professor Emeritus of History at Lycoming College. He has published several articles on Salem, Massachusetts during the Revolutionary era and has recently completed a book-length manuscript entitled, “Merchants, Mariners, and Mechanics Rising: The American Revolution in Salem, Massachusetts.” He may be contacted at Morris@lycoming.edu

Read Richard Morris’ article, “General Gage Comes to Salem: Interests, Ideologies, Identities, and Family Alliances Collide on the Eve of the American Revolution,” in the Spring 2022 issue of Early American Studies.

- Originally published in the Essex Gazette, June 14 and 21, 1774. Transcriptions available, see “Address of Merchants and Others, Inhabitants of Salem, to His Excellency Governour Gage, on Saturday, June 11, 1774” and “Address from the Merchants and Freeholders of the Town of Salem, Presented to His Excellency Governour Gage, on Saturday, June 18, 1774,” in American Archives, vol. 1, ed. Peter Force (Washington, D.C.: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1833), 402; 424-25. URL. (There are a few minor errors in Force’s transcription of the addresses that appeared in the Essex Gazette.) ↩

- Octavious Pickering, The Life of Timothy Pickering, 4 vols. (Boston: Little Brown, 1867), I: 54-56; John Andrews to William Barrell, August 25, 1774 in Letters of John Andrews, Esq., of Boston 1772-1776, ed. Winthrop Sargent (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Sons, 1866), 34. ↩

- Essex Gazette, September 13, 1774. ↩

- Essex Gazette, September 13, September 20, September 27, and October 25, 1774;

“Salem Town Records,” March 9, 1778, City Hall, Salem, MA. ↩