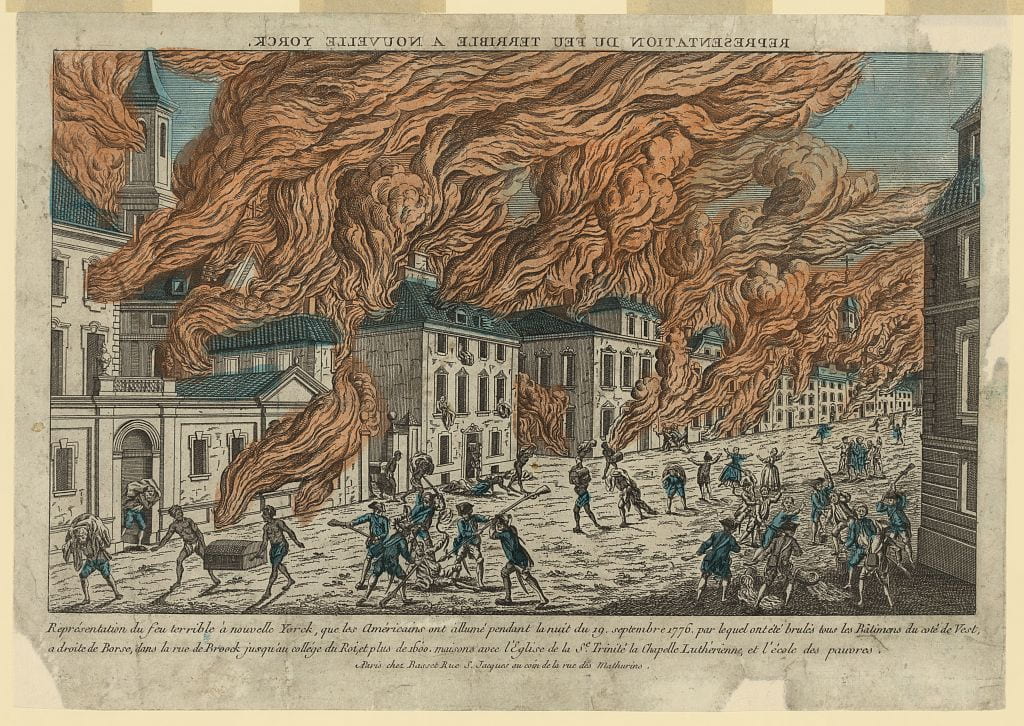

A widow who runs a tavern in Manhattan stands before a gathering of representatives, some loyal to the Crown, others interested in severing their ties with Great Britain and establishing a new government. A group of women, enslaved people, craftsmen, and others listen as she petitions the august body to recognize property and voting rights for women in New York, when suddenly a mob forms and storms the assembly. The game is afoot, and what happens next, only a roll of the dice will decide.

I teach history at the Armstrong Campus of Georgia Southern University in Savannah, where I work with the full range of students from freshman survey classes to master’s candidates. I first learned about Reacting to the Past when two colleagues told me about using it in their First-Year Experience classes. They brought an outside expert to campus to show faculty how to use a game set in the Peloponnesian War. Later, when I saw that a friend of mine was offering a session on Reacting at a conference, I made a beeline for it. In the session, students who had participated in the French Revolution game related their experiences and spoke to the value of playing the game. I was sold. The next semester, I scheduled Patriots, Loyalists, and Revolution in New York City, 1775-1776 for a course on “Colonial and Revolutionary America.” Aimed at juniors, it is open to all students seeking an elective as well as to history majors.

I have certain goals in every course I teach, and I had to be sure that the game would assist me in reaching them. Of course, I want to cover the time period in question, but beyond that, I strive to teach students certain skills: how to research a subject effectively, how to assess and organize information, and how to express their conclusions in writing and orally. Each Reacting game includes primary-source documents that the students read and discuss before play begins. It also comes with a quiz to assess comprehension. Once the game gets underway and students receive their roles, they have certain topics they must research to be able to make speeches to their peers, and they also have writing assignments, two short papers. These projects replace oral presentations and research papers I normally would assign in a class.

Using Reacting requires a significant time commitment and one of my worries going in was the loss of instruction time. The game takes four weeks, roughly a third of the semester, and I was concerned about sacrificing that amount of time and coverage. In a typical fifteen-week semester, I spend thirteen weeks leading up to 1775 and then the remaining portion of the class covering the American Revolution. The first time I used the game, I covered the colonial period in eleven weeks, and spent the remaining time in 1775 New York, with a lecture summarizing the remainder of the war on the last day of class. I rationalized the loss by pointing out I often post-hole topics in my classes. This was just a deeper hole than I was used to digging. I soon learned that what the students may have lost in coverage, they gained in nuance and understanding. Beyond that, playing the game resulted in something we all seek in our classes—engagement.

Students get extremely excited playing Reacting, and I have found that the various teams (Patriots, Loyalists, Moderates, Laborers, Women, and Slaves) meet outside of class and do extra research to prepare for the game sessions (sometimes to the detriment of their other classes, but frankly, I’m OK with that). Some, who have neither tested well nor uttered a word during the first part of the semester, begin expressing themselves through creative oral expression and carefully crafted essays. Their enthusiasm becomes infectious, their logical reasoning sharpens, and their ability to consider opposing points of view develops. As the Gamemaster, I have the ability to control the action. The students become energized, but they direct the energy themselves. My job is just to keep the students to task and prevent things from getting out of control, unrealistic, or fanciful. On the other hand, when the action becomes staid, I have the ability to introduce a wild card every now and again by adding a new plot twist, say the arrival of a delegation of Iroquois/Haudenosaunee representatives, when needed.

While some of my colleagues who use Reacting assign specific roles to specific students, I prefer to leave it to chance. As a result, students often play the role of people whose political stripes, genders, or races are different from their own. They immerse themselves, which opens their eyes to different points of view and possibilities. The “winner” the first time I ran the game was an older female tavern keeper played by a bearded twenty-year-old man. His speeches demanding representation were well reasoned, well supported, and incredibly inspiring. The outcomes of the game are also open to chance – there is no right or wrong answer or outcome, and anything can happen.

The first semester I used Reacting, I had a student who was barely scraping by and seldom participating in class discussions early in the semester. After she received her role, she took to it wholeheartedly. She blossomed because of the game and became one of my department’s best students. One day during office hours (playing the game even encourages that), she complained that it was frustrating that some of her classmates were not doing the reading and coming to class unprepared. I just smiled.

Christopher E. Hendricks is Professor of History at the Armstrong Campus of Georgia Southern University in Savannah, where he has been teaching since 1993. He has worked extensively in archaeology, historic preservation, and museum interpretation with many organizations including the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Old Salem, Inc., and the Historic Savannah Foundation. He is the author of numerous publications, including The Backcountry Towns of Colonial Virginia and Old Southern Cookery.

Links to Other Teaching with Games Roundtable Posts:

The Royal Geographical Pastime: A Game from 1770 – Holly Brewer

Indigenous Perspectives and Historical Empathy – Maeve Kane

Gaming the Framing: To Teach the Convention, the Constitution, and the Founding – John Patrick Coby

Reacting to the Past for Early Americanists – Elizabeth George

Controlled Chaos: Roleplaying Revolution in Southeast Texas – Brendan Gillis

Harnessing Competitiveness for Good in RTTP Games – Brett Palfreyman

See the Q&A feature for a summary of the roundtable’s key ideas.