Class was over. It had been over for five minutes. I could see the next class growing restless in the hall. I interrupted a heated exchange among my students with an “ok, we’ll decide if he lives or dies next time!” The students immediately broke into smaller groups, everyone talking quickly, even as the next class came in and forced them away from the tables. This is a typical class period when teaching with Reacting to the Past games. As the instructor, the effort required to get the game up and running feels like launching an airplane, but once it is going and students hit a point of total immersion, the feeling is so intoxicating that you go back to it again and again.

Is this teaching? While some traditional teaching skills, such as attending to learning goals, being organized, and building relationships with students, are essential for a successful game, Reacting refers to instructors as “Gamemasters,” and that term seems more accurate. You do your best to set the perfect conditions by guiding the students through the primary sources and assigning roles. You then watch as you let students loose to make of it what they will.

I have used early American themed games in U.S. history survey and upper-level Colonial America courses. I have run games with as many as sixty students and as few as five. I have used games, such as Forest Diplomacy or Patriots and Loyalists, which take two weeks or more to play, as well as shorter Flashpoints, or microgames. The latter are condensed versions of Reacting games that focus on a single historical incident and confine gameplay to only two or three class periods. I have had some games that soared and others that only floated, but, to me, the benefits outweigh any challenges.

When I started using Reacting games ten years ago, I tended to deploy them as stand-alone units. Now, I integrate them more seamlessly into my courses by emphasizing the relevant content and skills students need for successful gameplay throughout the semester. Games also help me fulfill learning goals, including building a community of learners among students and helping them to understand how historians analyze and contextualize primary sources. Starting on the first day of class, I use pedagogy and content that will help us have a successful game, whether that means having students practice reading primary documents or giving them short assignments in which they have to imagine what a historical figure felt like during a historical event. For example, Forest Diplomacy includes roles for “interpreters” or intercultural negotiators. To prepare students, I introduce the concept of a “go-between” in the earliest lessons on Jamestown and then reinforce the idea in the lessons leading up to the game. This pays off in gameplay when the interpreters recognize the power they can exert by allocating their time and attention either to the Quakers or the Native Americans. In addition, even after a game is complete, it continues to shape student learning because they have a shared experience they can reference for the remainder of the semester. As we continue to discuss the role interpreters played in a variety of early American cultural contexts, students can refer back to that critical role in the game, and those who played interpreters can refer back to the feeling of power they experienced. The games, therefore, serve as cornerstones in the course, shaping content, discussions, and experiences.

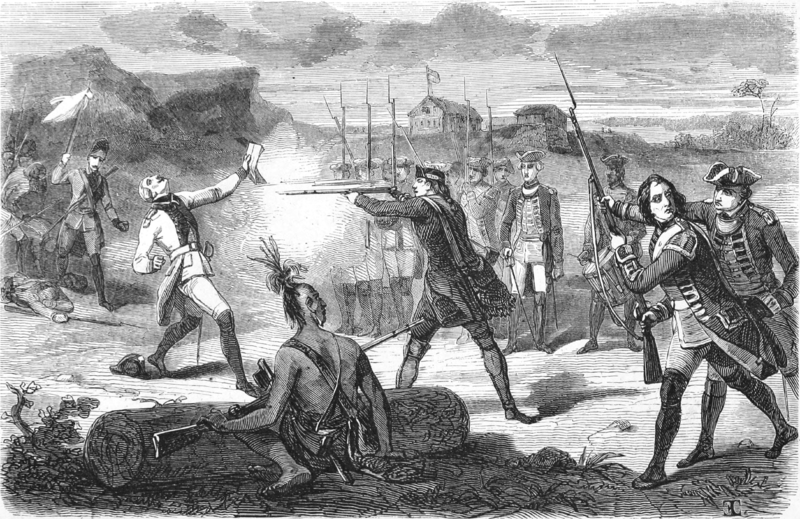

Using the games to teach does come with challenges. In general education courses, I find that the shorter Flashpoints games work better than full Reacting games, as it is easier for less-invested students to sustain energy and interest over the course of one week rather than two or three. There are also challenges unique to early-American-themed games. Both Forest Diplomacy and The Jumonville Incident ask students to play Native American roles. The instructor has to be careful to provide enough historical context from the first day of class so that students understand how to approach these roles. The game book addresses these kinds of concerns, and it is essential for instructors and students to read those sections carefully as a class. Similarly, in some games, such as Patriots and Loyalists, I often find that modern students are already predisposed toward one side, which makes it difficult to start the game on equal footing. In navigating both scenarios, it is critical for the instructor to find students who will play challenging roles well. From the first day of class, I am on the lookout for students who value looking at an event from multiple perspectives and who can take on the challenges of the more complex roles. During the game I am in contact with them to make sure they stick to their role sheet and pursue their character’s victory objectives.

There are many great things about using Reacting games, but perhaps the best is that students remember the experience, the content, and how the past came to life. I have had conversations with students years after a game and they remember the details of their role, the negotiations, and how our outcome differed from the historical record. That payoff is worth the extra effort.

Elizabeth George is an Associate Professor of History at Taylor University in Upland, Indiana. Her research interests include women and early American wars and how to effectively use active learning strategies in the classroom.

Links to Other Teaching with Games Roundtable Posts:

The Royal Geographical Pastime: A Game from 1770 – Holly Brewer

Indigenous Perspectives and Historical Empathy – Maeve Kane

Gaming the Framing: To Teach the Convention, the Constitution, and the Founding – John Patrick Coby

Building Student Engagement with Reacting to the Past – Christopher E. Hendricks

Controlled Chaos: Roleplaying Revolution in Southeast Texas – Brendan Gillis

Harnessing Competitiveness for Good in RTTP Games – Brett Palfreyman

See the Q&A feature for a summary of the roundtable’s key ideas.