Who We Are

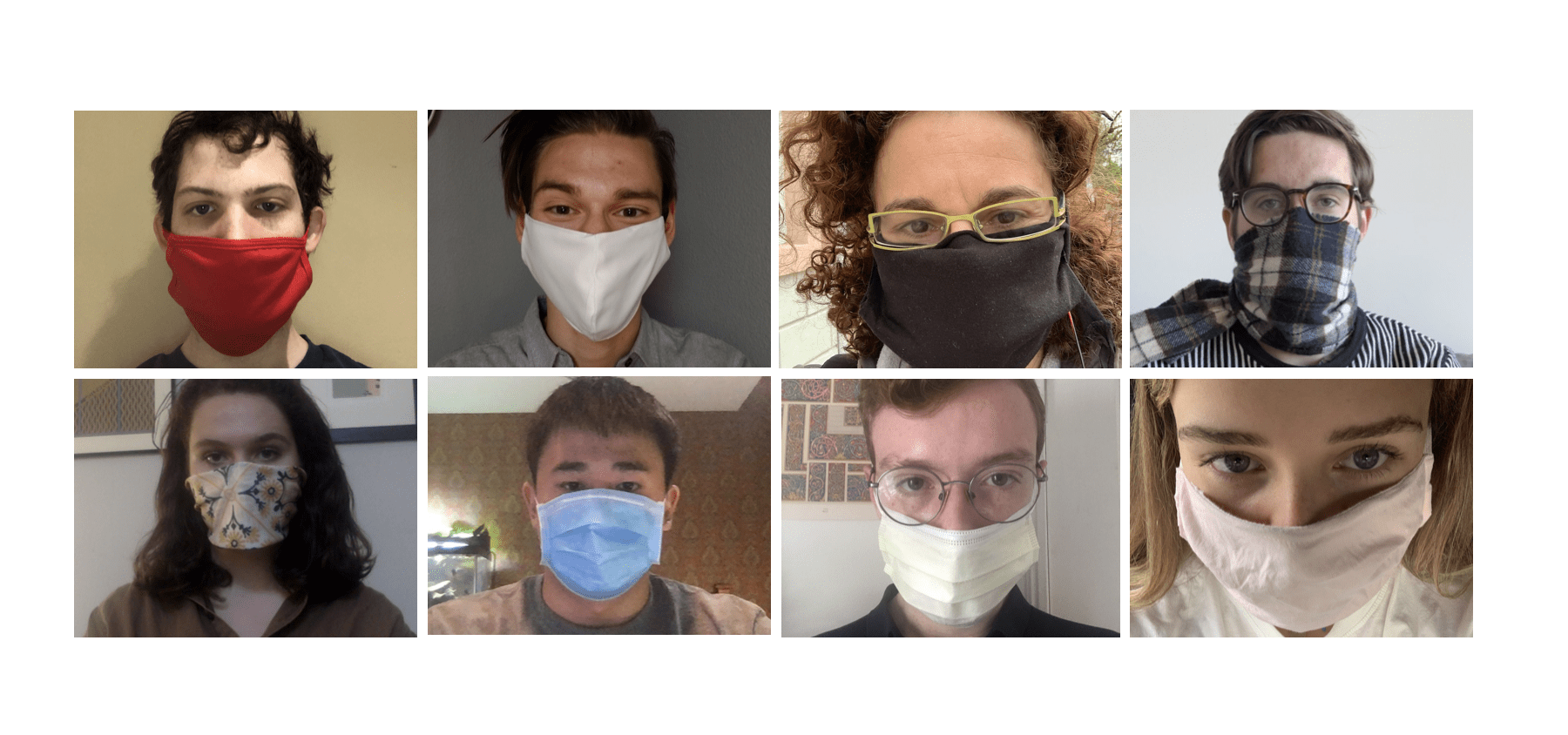

We are a collaborative group of researchers, who, as part of a University of Pennsylvania History class, got “stuck on” Earth Day for a number of rather fortuitous coincidences and decided to at least “unmask history” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

On the surface, one would not expect our class “Wastes of War: A Century of Destruction” to have anything to do with Earth Day. Our class approaches war as a process rather than a neatly bounded event, which allows us to examine the human and environmental consequences of violent conflict throughout 20th century, with a particular focus on the “stuff” that lingers on, the externalities, the wastes that war and militarism invariably produce and scatter.

War-making violently transforms social and physical environments, reshuffles ideologies, reimagines futures and reshapes alliances; alters bodies, habitats, and cultures. In our shared readings we approached war as an engine of destruction and transformation rather than as politics gone awry.

In our discussions we traced how the language of war and embattlement is applied to a whole host of different kinds of problems that require systematic, coordinated, and often unpopular sets of response. The “war” against the current pandemic serves as pointed example.

Informed and, we would say, indebted to civil rights and anti-war activists, Earth Day organizers and the nascent environmental movement imagined a planet besieged and embattled by pollution and overpopulation. Some who followed in their footsteps extended the belligerent language to questions about inner cities, waging wars on drugs and crime, building on the (perhaps inadvertent) racist overtones that shaped what historian Thomas Robertson has terms The Malthusian Moment.

How We Got and Why We Stayed “Stuck” on Earth Day

Now that we have done most of the research, the connections between our class project and Earth Day are more clear, and to some extent they may also be a product of the particular lens we applied. But that wasn’t case initially.

Before there was a pandemic, our class got pulled into the preparations for Climate Week at Penn – the organizers needed someone to look into the history surrounding the first Earth Day and the way in which it inspired a whole week of events in Philly. After just a short discussion and some preliminary research we got “stuck” on the project and decided to devote our classroom based research time to telling the story of Earth Day in new ways. Our findings are certainly less celebratory and the story we tell focuses on discontents of Earth Day in order to draw some important historical lessons as we face a future of climate disruptions.

It turns out Earth Day wasn’t invented at Penn. The Declaration of Interdependence, declared at Independence Mall, forgot about a lot debts and glossed over a lot dependences. History doesn’t repeat itself, but unless the mistakes of past are made visible, they have a way of seeping into the future.

As long as the privileged among us talk about saving the planet for all, those who live in perpetual precariousness will continue to feel as though their livelihoods are at best afterthoughts. If we want to safe the planet at all, we need to save it first for the most vulnerable among us.

Environmentalism owes a debt to black activists first and foremost, to antiwar and feminist activists, to organizers and citizens across the world, who invested into building a more just and equitable world and who were too often ignored or sidelined by more powerful, better connected interests . If climate activism will have any chance of success, it will have to acknowledge those debts and start repaying them.

The Earth Day Projecteers (in reverse alphabetical order)

Noah Sylvia is a student in the College of Arts and Sciences currently studying International Relations, with a focus on conflict and war. He is a student of military history, and researches military technology for the Political Science department. He is currently quarantining in Fort Hood, Texas.

Noah Sylvia is a student in the College of Arts and Sciences currently studying International Relations, with a focus on conflict and war. He is a student of military history, and researches military technology for the Political Science department. He is currently quarantining in Fort Hood, Texas.

Charles Li Charles Li is a senior at Wharton, concentrating in finance and management. Stemming from his passion for the outdoors, he is interested in the dynamics between the environment and war. He is currently residing south of Kansas City, Kansas.

Charles Li Charles Li is a senior at Wharton, concentrating in finance and management. Stemming from his passion for the outdoors, he is interested in the dynamics between the environment and war. He is currently residing south of Kansas City, Kansas.

Eva Karlen is a junior in the College of Arts and Sciences studying labor history, environmental history, and political ecology. She is a member of Fossil Free Penn.

Aidan Goodchild is a current Junior at the University of Pennsylvania studying European History from Wayne, Pennsylvania. Aidan on Campus is the President of Penn Public Policy Consulting and was formerly involved in the SFCU. Aidan is interested in military history, economic history, and philosophy. He is currently quarantining in Philadelphia.

Aidan Goodchild is a current Junior at the University of Pennsylvania studying European History from Wayne, Pennsylvania. Aidan on Campus is the President of Penn Public Policy Consulting and was formerly involved in the SFCU. Aidan is interested in military history, economic history, and philosophy. He is currently quarantining in Philadelphia.

Graham Cuddy is a student at The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and Penn. At PAFA he is primarily focused on painting while at Penn he is focused on art history. He currently resides in Philadelphia.

Finnegan Biden is a current Junior at the University of Pennsylvania, originally from Washington D.C. She is majoring in History and concentrating in American studies. She is also pursuing a minor in Art History

Anne Berg is a historian, garbologist, activist, thinker and writer who lives in Philly, teaches at Penn and follows the scat of the past to wherever it leads. A more elaborate bio sketch can be found here.