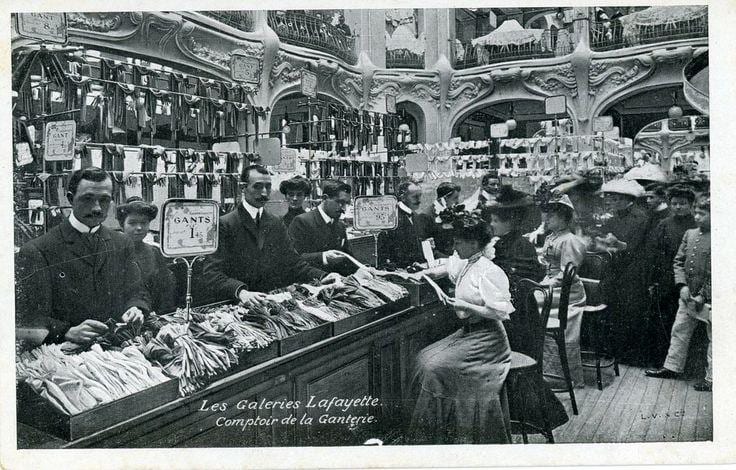

Les Galeries Lafayette represent the turn to modern commercialization that began in the middle of the 19th century, when there was a radical shift in the culture of Parisian retail. The intertwined phenomena of, on the one hand, industrialization and mass-production, and, on the other, the development of new urban public spaces, changed the degree of access and the manner by which the bourgeoisie were exposed to and acquired commodities—especially, in this case, fashion.

Small specialty shops selling bespoke or few items, often hidden behind counters, were replaced by large department stores, initiating a culture of browsing. Arranged displays and printed catalogs codified consumers’ choices into a variety of options—options that were nevertheless limited by their eventual obsolescence in the face of what would become seasonal trends. In fact, the name “Galeries” derives from the store’s interior arrangement, with lines of ‘galleries’ filled with product displays through which consumers could freely roam, resembling the typology of the arcade (and all that Walter Benjamin would eventually attribute to that type). This culture of browsing—of looking around—eventually fused with the broader trend of being looked at, of being seen and of social performance, giving rise to “fashion” as a rapidly-changing, ever-evolving mechanism of self-presentation. The continuous replacement of last season’s trends with the new products showcased in these stores reflected and propagated an increasing aesthetic emphasis writ large on the temporality of modern, urban life in Paris.

Postcard of Les Galeries Lafayette, Comptoir de la Ganterie (Glove Counter), ca. early 1900s (Rue Marcellin)

This cultural shift also allowed for new mythologies of commodification—a social construct of which Les Galeries Lafayette took full advantage, promoting the story of their rapid rise from a small business to a blossoming international success. In 1893, Théophile Bader and Alphone Kahn opened a local haberdashery on the intersection of Rue La Fayette and Rue Chausse d’Antin, situated in prime real estate near the Operà, the Grands Boulevards, and Gare Saint-Lazare. In 1896, they bought the entire building at 1 Rue La Fayette, and, in 1903, purchased 38, 40, 42 on Blvd Haussmann, and 15 Rue Chausse d’Antin, all of which were chosen to create the largest possible contiguous commercial space.

Photograph of the entrance to the Galeries Lafayette, taken in April of 1914. (Wikimedia)

Les Galeries grew out of an increasingly interwoven landscape of department stores springing up around Haussmann’s Paris: Le Bon Marché (1852), Les Grands Magasins du Louvre (1855), Les Grands Magasins du Printemps and La Samariteine (both 1865). The Exposition Universelle (1867) would then compliment and propagate browsing culture, classifying the overwhelming number of objects in a taxonomic manner typical of the 19th century, and eliding art with commodity. (Not by chance, World’s Fairs’ categorization of objects by both nation and type mirrors the concept of a holistic commercial enterprise subdivided into “departments” for shopping convenience.) When built, Les Galeries Lafayette were just one of an expanding genre, yet they remain one of the most potent symbols of this shift toward commercialism due to their particular and continued success, which was aided—if not ignited—by the store’s architectural extravagance.

In 1907, Bader, looking to revamp, commissioned the architect Georges Chedanne (1861-1940), whose most impressive contribution to the store (and to his career) would come a bit later in 1912, when he and his apprentice, Ferdinand Chenut, constructed an immense glass dome atop the store’s so-called “Grand Hall,” illuminating the goods for purchase inside.

Construction of the dome, ca. 1912. (ArchDaily)

The dome of the Galeries Fayette. (BBC)

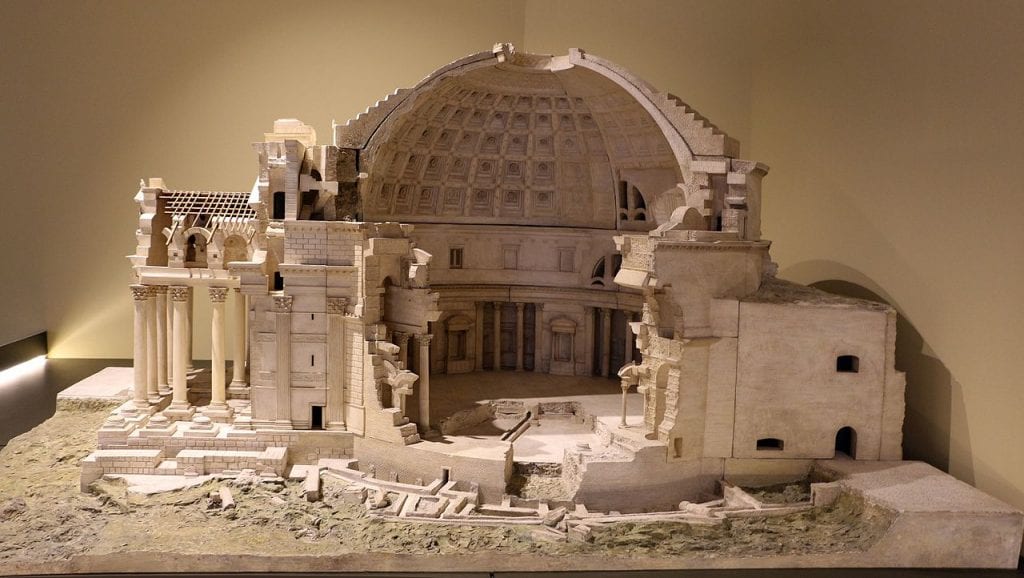

The dome, rising 43 meters, is an operatic art nouveau synthesis of iron and stained glass, reflecting Emile Zola’s description in Au Bonheur des Dames (1883) of the Parisian department store as “the cathedral of modern commerce, solid and light, made for a people of customers.” Chedanne’s inspiration, however, may have been even more ancient than the cathedral: as a recipient of the Prix de Rome in 1887, he studied the Pantheon and its dome extensively, even meticulously constructing a scaled plastico of the structure, now displayed in the Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia in Milan.

Georges Chedanne, plastico of the Pantheon, 1892-1893 (Wikimedia)

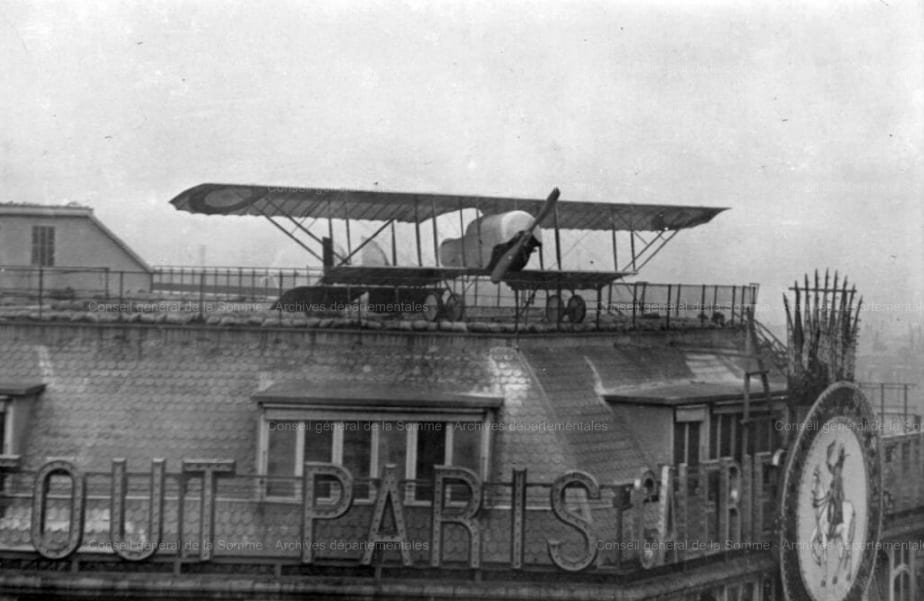

Chedanne’s ‘spectacularization’ of commerce crowned what would soon become a robust brand. Bader enhanced the prestige of his store by forging exclusive contracts with the textile merchants and fashion designers du jour, ensuring that his products adhered to the aesthetic milieu of Parisian demand. Bader also augmented the establishment’s publicity by hosting events of a particularly modern bent, including pioneering occasions in aviation—such as when the celebrated pilot Jules Védrines, in a staged stunt, landed his Caudron G.3 (“La Lafayette”) on the store’s roof, where it remained on display. As a result of Bader’s efforts, to go shopping “aux Galeries” became a socio-cultural experience that complimented the performative quality of the clothes sold there. Bader doubtless understood that fashion had become a symbolic mechanism to define bourgeois status—an iconography of its own—characterized by the merging of aesthetics, reproduction, and capital, whereby the repetition of products and trends fostered recognition, cohering ‘in group’ association.

Jules Védrines’ Caudron G.3 plane, “La Lafayette,” displayed on the roof of the Galeries. (Messy Nessy Chic)

During the Meiji era and the subsequent emergence of a global market broadly conceived, similar trends began occurring in Japan. Gofukuten, textile stores specializing in fabrics for kimono and obi, took advantage of the new opportunities available to them, and their participation in foreign exhibitions propagated the interests of these store owners in their own display mechanisms and advertising techniques.

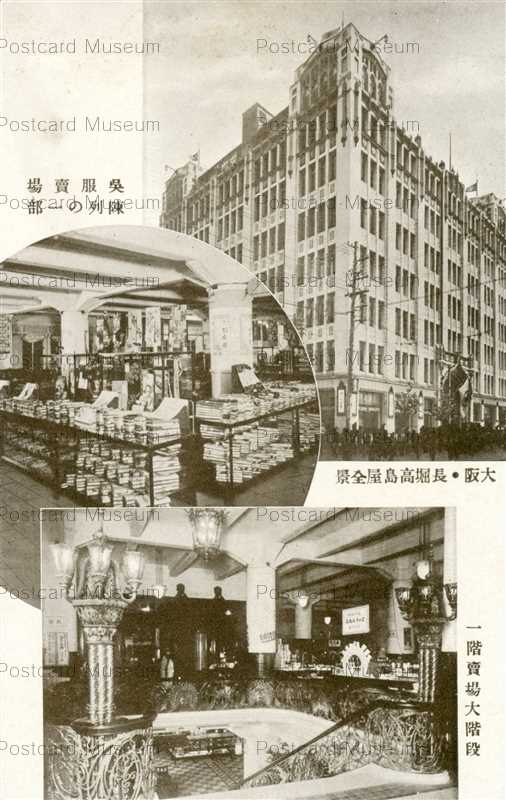

Kyoto’s Iida Gofukuten Takashimaya experienced a similar rise as Les Galeries Lafayette, and capitalized on this new mythology of enterprising commercialism in a similar manner, promoting the narrative of humble beginnings transformed into an internationally-recognized brand. In 1855, Iida Shinshichi II took over his father-in-law’s used kimono shop in Kyoto, near the corner of Karasuma and Takatsuji streets. He quickly expanded the merchandise, turning the store into a veritable gofukuten for new kimono. 1878, he purchased another building down the street where he installed an art textiles department, which rapidly grew and expanded into its own establishment and opened stores of its own in Osaka (1898), Yokohama and Tokyo (1900), Kobe (1901), and Lyon, France (1899), the latter of which specially catered to a foreign market.

Takashimaya also began to use display cases, which allowed customers to view a fixed set of products displayed up close, rather than having to ask for what was kept behind the counter. In 1912, the same year the dome was built on Les Galeries Lafayette, the Kyoto branch was rebuilt into a lavish modern structure, effectively converting into a department store. It was divided into three floors, the first for textile purchase, the second for finished products, and all topped by a restaurant, ensuring its visitors an immersive commercial experience similar to the architectural condition of Les Galeries. Instead of customers sitting in the ‘selling area’ as they had before, now they browsed on the move.

Takashimaya department store in Kyoto, in 1912. (Takenaka)

Postcard of Takashimaya’s Osaka branch. (Ehagaki)

Just as Les Galeries enhanced its brand with exclusive contracts with fashion designers, Takashimaya, in turn, teamed up with artists, such as Kishi Chikudo (1826-97), Kono Bairei (1844-95) and Takeuchi Seiho (1864-1942), who all created art textiles (bijutsu senshoku) for the store. Most were nihonga painters, and their fame was mechanized as a mode of commercial advertisement. Other new Japanese department stores did the same. In Tokyo, Mitsukoshi (1895) employed nihonga painters from the Tokyo School of Fine Arts to design kimono, and, along with Takashimaya, hired yōga painters to create billboards, posters, flyers, and other advertisement ephemera. As a result, these department stores embedded themselves into popular consciousness, as their appearances in various ukiyo-e ‘famous places’ series render palpable.

Koizumi Kisho (1893-1945), Mitsui Bank and Mitsukoshi Department Store (1929), from One Hundred Pictures of Great Tokyo during the Showa Era. Polychrome woodblock print. (Photograph by author)

Takashimaya sent representatives to international and domestic exhibitions, where they often displayed wall-hangings. For the foreign exhibitions, most were kachoga (bird-and-flower motifs), a subject intended to suit foreign tastes. The materials in domestic displays usually featured historical or mythological and Shinto scenes. As Julia Sapin has argued, these themes became signifiers of Japanese culture abroad and of national identity at home: “Through their liaisons with Takashimaya, Kyoto nihonga artists expanded their role as merchants of culture, culling certain images from the past and discarding others. They imbued textile design with pictorial intensity. These designs echoed painting styles that became harbingers of national aesthetics, which have become part of the definition of nihonga.” Similar to how the fashions sold at Les Galeries Lafayette became a mechanism of defining new bourgeois identity, so too did Takashimaya’s products help to forge cultural recognition in a Japan that was in the midst of redefining itself.

Kawashima Jinbei II (1853-1910) for the Kawashima Textile Company, Group of Peacocks, Cherry Trees and Magnolias in Bloom, ca. 1908. Silk tapestry with metallic filaments. (Photograph by author)

Further directions of inquiry, however, might consider diving deeper into the nature of the customers themselves and into the nuances inherent in such identities. In tandem with new studies on the Japanese middle class during the Meiji era, the question emerges of how homogeneous these nationalist sentiments actually were, and how geographic regions and cities may have differed in this regard. Likewise, conceptions of French consumerism in the 19th century tend to derive from considerations of Paris exclusively, subsequently leaving out most of the country’s population. How might conceptions change if the rest were incorporated into the account?

—Alyssa Cody Garcia

Selected Bibliography

Jeehyun Lee (2011), “Resisting Boundaries: Japonisme and Western-Style Art in Meiji Japan,” PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania.

Dennis McNamara (1995), Textiles and Industrial Transition in Japan, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Younjung Oh (2014), “Shopping for Art: The New Middle Class’ Art Consumption in Modern Japanese Department Stores,” Journal of Design History 27(4): 351-369.

Robert Proctor (2006), “Constructing the Retail Monument: The Parisian Department Store and its Property, 1855-1914,” Urban History 33 (3): 393-410.

Julia Sapin (2004), “Merchandising Art and Identity in Meiji Japan: Kyoto Nihong Artists’ Designs for Takashimaya Department Store, 1868-1912,” Journal of Design History 17(4): 317-336.