Hello,

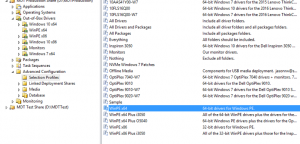

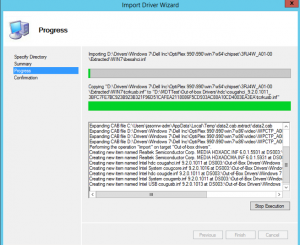

This post is a follow-up or compliment to creating an image of Windows for mass-distribution (Windows 7). On that note as well, the folks over at Deployment Research have a great post on creating an updated Windows 7 master image with MDT, very helpful.

This summer, Windows 10 is upon us, and we have already begun slowly transitioning some areas to Microsoft’s ultimate operating system. Largely, the process of making an image for Windows 10 is the same that is was for Windows 7 with a few twists.

Tools…

I like to build my images in a virtual machine. This approach allows me to create an image that is truly hardware-neutral. Using actual hardware could work, but there still may be remnants of that hardware that sysprep does not generalize, and could potentially make it into production. The actual hardware approach worked for Ghost, but it is not necessary anymore with MDT. Choose whatever virtualization tool out there, they all work very well, some are even free. Here’s the best of what’s around:

- VMware Workstation/Player – Not free, but feature-rich and integrates into vSphere.

- Microsoft Hyper-V – Comes with x64 server versions of Windows (2008 and later), and x64 desktop versions of Windows 8 and later. Despite all of the “server” nomenclature, client operating systems will work just fine.

- Oracle VirtualBox – Free, and available for Windows, macOS, and Linux as both the host OS and the client OS.

I am aware that there are virtualization products for macOS, and Linux, but we’re working with Windows. I think it is best to just stick with that for the whole process. I’m sure everything would be fine if Windows was not the host operating system.

Given that, you’re going to want to do this work on a moderately beefy PC. Not all of us have Dell Precision workstations, or even access to a server with Hyper-V or vSphere installed, but using an under powered PC will make building images, and just using virtualization a slow and miserable experience. The key is storage. Creating images, multiple images with snapshots, and testing uses up a great deal of space on the disk drive(s). I would not bother using a drive smaller than 1TB. It’ll work on something smaller, but in that case, you are limiting the whole process. Even 1TB SSDs are reasonably priced now. SSDs are king, but still not equal to spinning disks in price per gigabyte. A combination of something like a 256GB SSD for the host operating system and applications with a 4TB spinning HDD for storage would work well. RAM is also very important because, when using VMs, RAM is being used by both the host and guest operating systems, at the same time. Try to max-out what your PC will take. 32GB, 64GB of RAM is not unreasonable for this type of work.

Modern CPUs are plenty powerful for many tasks, virtualization too. Intel CPUs have extensions specifically for virtualization. Quad-core CPUs should be a pre-requisite for a host PC that will do virtualization. You could use a dual-core CPU, but recall the part from above about under powered PCs and virtualization. If you can get a CPU with more cores, 6, 8, great! Xeon CPUs are really nice. I wouldn’t bother with anything under a quad-core i7. Another thing to also consider, that is sometimes overlooked, is bus speed. You could have the fastest CPU with many cores, a ton of RAM, working off a sweet 2TB SSD, but if the bus that connects all of these devices together is small, all you are creating is a digital traffic jam. NVMe, and M.2 SSDs are slowly replacing SATA-based SSDs and spinning HDDs in consumer and business PCs. They offer a significant increase in throughput and speed for data storage. DDR4 memory is the latest and greatest in RAM technology, until 2020, when DDR5 is expected. It is not the cheapest, but DDR4 outperforms all of its predecessors. Obviously, you want to get the best set up you can, but I understand budgets have limits.

Virtual Machine Settings…

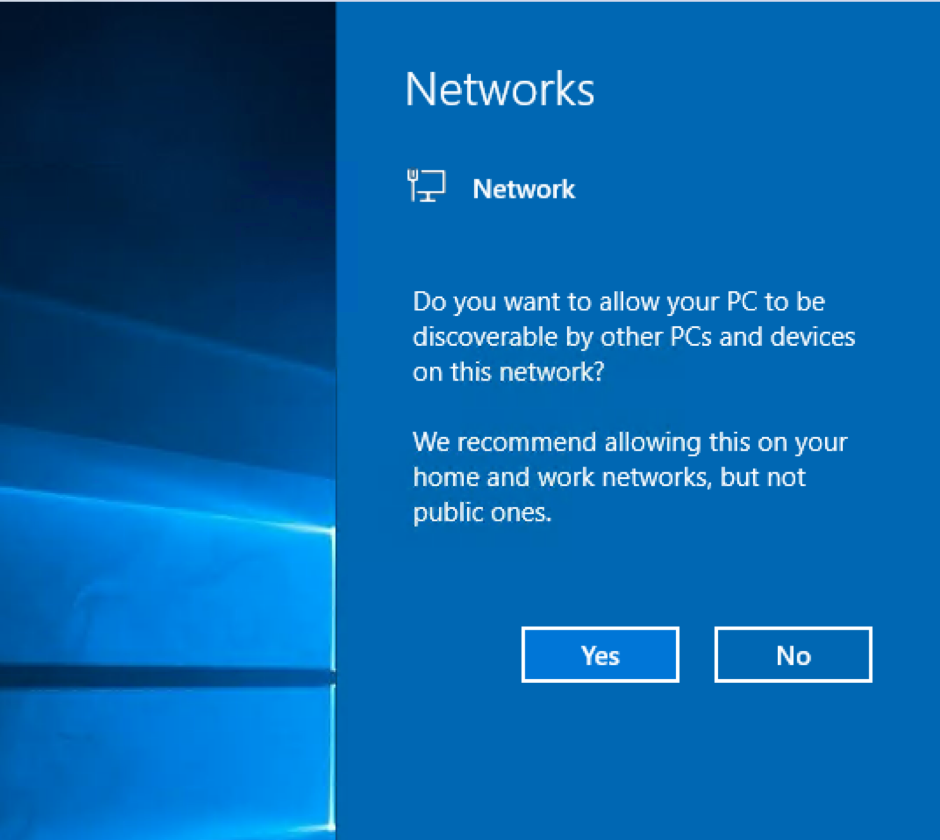

This can vary from place to place, but I would use at least 4GB of RAM, one vCPU with 2 cores, and a 128GB VHD. That has worked well for me with Windows 7 and 10. If you can give the VM 8GB of RAM, do it. The smallest disk drive we have out there is a 128GB SSD in some Dell OptiPlex 9020s we purchased in 2014. When finished, my image has a disk footprint of around 70GB (35GB compressed by dism). If the new image will be small, then a 64GB VHD is fine. That is as small as I would go. It is possible to squeeze an image of Windows 10 (plus updates), Office 2016, Adobe Reader, Chrome, VLC, and AV software onto a 32GB drive, it is a tight squeeze. Windows grows in size over time, and 32GB will be gone long before you even realize it. I’m starting to think 32GB is too small for an iPhone… The virtual NIC should be configured for NAT, and not bridged to the production network. We’ll have a fresh install of Windows, straight from the ISO, and temporarily unpatched. The image should not see the production LAN until it is ready for testing (patched), or ready for use.

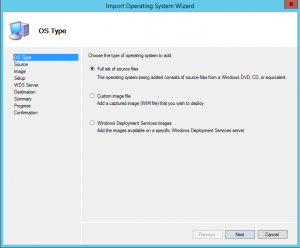

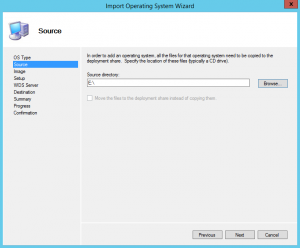

OS Installation…

After the guest VM is created for the new image, connect its virtual CD/DVD-ROM drive to the ISO file for Windows 10. In VMware Workstation, new VMs, with no OS installed, automatically boot to the virtual CD/DVD-ROM by default.

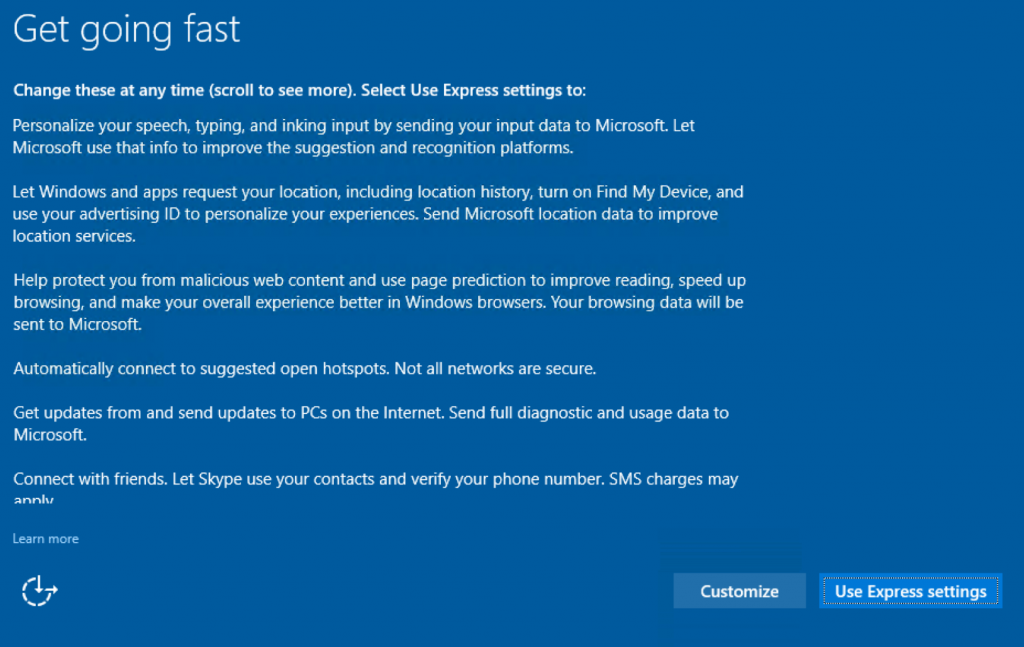

Follow the on-screen prompts to install Windows into the VM, but STOP after the first reboot from install/file copy to OEM/Windows setup. Setup will stop at that point, and wait for user input. There, we’ll use audit mode to finish setting Windows up the way we would like it. I have more information about installing Windows 10 in a separate post.

To get into audit mode, press control + shift + F3 all at the same time, like the three-finger salute (control + alt + delete). Windows will reboot, and automatically log in as the built-in administrator account, and will continue to do so, no matter how many times you reboot, until sysprep is run. Here, we’ll customize Windows 10 as desired, then run sysprep with an unattend.xml file that copies our profile over to the default (CopyProfile).

From within your virtual machine software, take a snapshot of the VM, at this point.

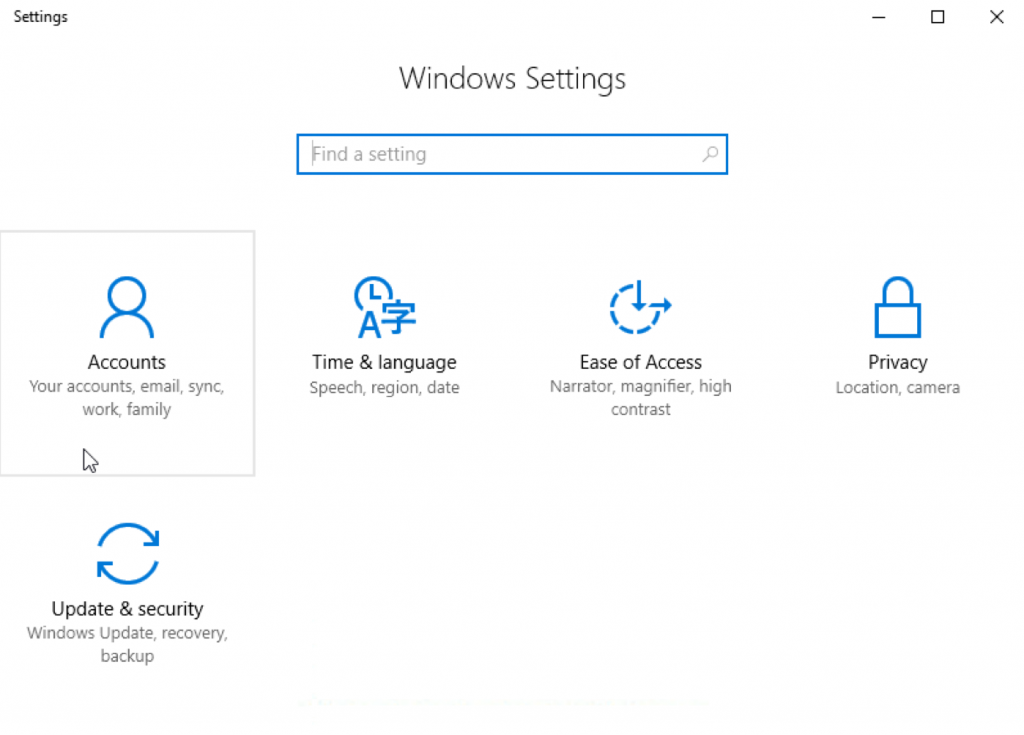

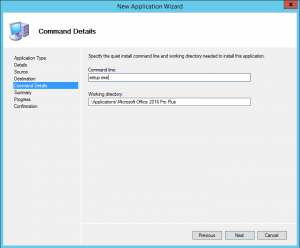

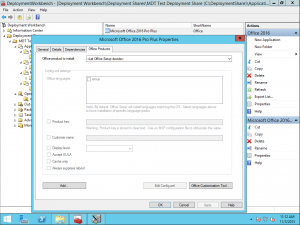

Most corporate or “work” PCs have Microsoft Office installed along with Windows and other common programs. Microsoft/Windows Update is used to update both Office and Windows. At this point, I install Office (silently with a MSP file), and enable Windows to update other products in addition to itself. This is done from the new Settings application \ “Updates & Security” \ “Advanced options” \ “Give me updates for other Microsoft products when I update Windows.”

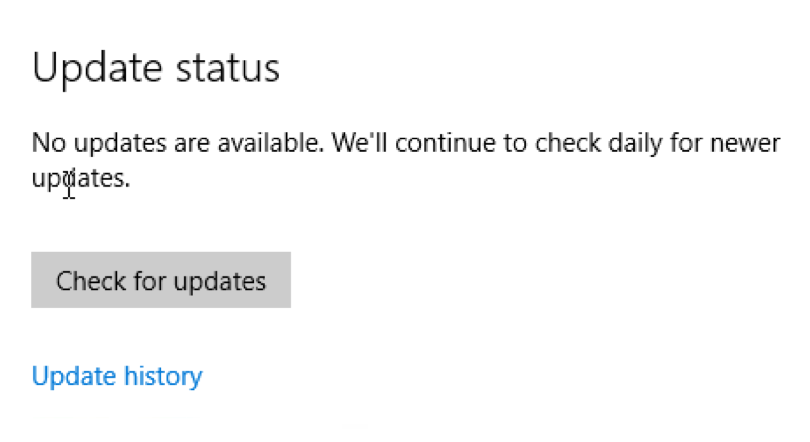

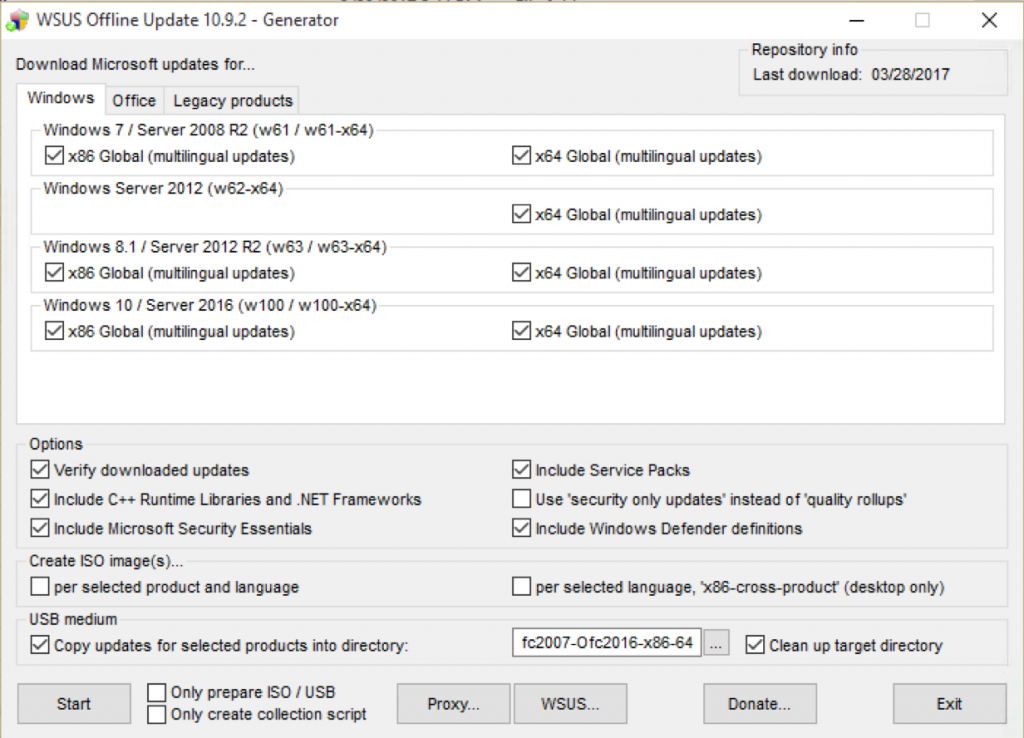

Once that is set, run updates on the new VM until there are no more left. The later the build of Windows 10, the fewer updates will be required. Microsoft Office 2016 has been available for some time, and has a decent amount of available updates online. Once the updates are finished, shut down the VM, and take another snapshot.

Some basic applications, which are not included with a regular install of Windows, are utilities that other applications use. Applications like the various Visual C++ Redistributables (VCPP), Microsoft Silverlight, and Updated .NET Frameworks (4.5/4.6). These are easily found online, and can be installed silently. The Deployment Research site has a script that gathers all of the C++ Redistributables together, and installs them, silently, in one script.

Download the VCPPs from the Microsoft website (both x86 and x64), and move them to a folder structure named as follows: (#### = the date for the VCPP application, 2005-2015)

Source \ VC#### \ vcredist_x64.EXE

Download all of the VCPP apps for x86 and x64 versions 2005, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2013, and 2015 and arrange them like above.

The script to install all of these can be found here.

Silverlight is also freely available from Microsoft’s website.

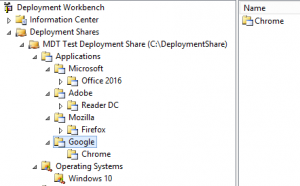

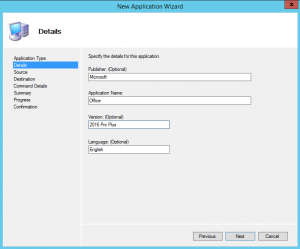

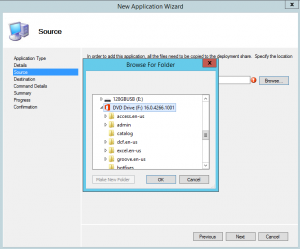

Next, is to install all of the regular applications that people use every day. Web browsers like Google Chrome, or Mozilla Firefox, PDF readers like Adobe Reader, or SumatraPDF, communications application such as Skype or Zoom, and multimedia apps like VLC, or iTunes. I download, and store the applications I intend to use on a server share, then use silent install scripts to install them on Windows 10, which is still in audit mode.

Some basic silent install commands for common applications. If you’re in for more details, check out ITNinja.com. They have a compendium of unattended and deployment-related information for many applications.

- Adobe Reader: msiexec /qb /i AcroRead.msi TRANSFORMS=AdobeReaderDC.mst

- Google Chrome Enterprise: msiexec /qn /norestart /i “GoogleChromeStandaloneEnterprise.msi”

- Mozilla Firefox: FirefoxSetup.exe -ms

- VLC: vlc-2.2.1-win32.exe /L=1033 /S /NCRC

- Java (if you must): jre-8u66-windows-x64.exe” /s JAVAUPDATE=0 AUTOUPDATECHECK=0

- Notepad++: npp.6.8.7.Installer.exe /S

- 7-Zip: msiexec /q /I 7z920-x64.msi

Ninite.com has a site that will create a wrapper as an executable that will download whatever freeware is chosen and install them. All in one go.

Keep in mind that the fewer applications that are placed into the image, the longer that image will stay relevant. MDT/SCCM can deploy applications in addition to the OS itself. Products like Adobe Flash Player, and Adobe AIR change so often that I just install them when the image is deployed.

Run each of the newly-installed applications and configure them as desired. Shut down, take a snapshot, then reboot and let Windows 10 continue in audit mode.

To save time and effort in configuring Windows the way I need it, I try to automate as much as possible. Scripting the basics and eliminating the redundant and repetitive tasks can save a lot of time and prevent unnecessary mistakes.

Creating user accounts – I typically make a local user account for administrative use and for general use in case the domain is somehow unavailable.

First, I create a local folder to contain log files and other goodies, then hide it. “C:\Stuff” in this example.

mkdir C:\Stuff

attrib +h C:\Stuff

echo Creating local user accounts

net user pcadmin * /add /comment:”Local admin account” /passwordchg:NO

wmic useraccount where “name=’pcadmin'” set passwordexpires=FALSE

net localgroup “Administrators” pcadmin /add

net user pcuser * /add /comment:”Local user account” /passwordchg:NO

wmic useraccount where “name=’pcuser'” set passwordexpires=FALSE

net localgroup “Guests” pcuser /add

echo Local user accounts created on %date% at %time%>>C:\Stuff\Windows-10-Config-Script.txt

The asterisk (*) after the username will prompt for the new user’s password instead of coding it into the script and leaving it for prying eyes. The last command (echo…) will create a text file and add the text between echo and the first >. The double >> will just add the text to an existing file should that be the case.

To keep from surprising users with new builds or versions of Windows 10 through Microsoft Windows Update, I set a registry key to disables Windows upgrades through updates.

reg add “HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Policies\Microsoft\Windows\WindowsUpdate” /v DisableOSUpgrade /t REG_DWORD /d 1 /f

echo Windows 10 version upgrade disabled on %date% %time%>>C:\Stuff\Windows-10-Config-Script.txt

The next thing I want up and running right off of the bat is remote desktop.

echo Enabling RDP with SASC alternate port

reg add “HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Terminal Server” /v fDenyTSConnections /t REG_DWORD /d 0 /f

reg add “HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Terminal Server\WinStations\RDP-Tcp” /v “PortNumber” /t REG_DWORD /d “0xdesired_port_number_in_hex” /f

netsh advfirewall firewall add rule name=”Alternate RDP Port” dir=in action=allow protocol=TCP localport=desiredportnumberinbase10

echo RDP enabled with SASC alternate port on %date% at %time%>>C:\Stuff\Windows-10-Config-Script.txt

A facet of Windows’ default configuration is to hide file extensions. I can guess the designers at Microsoft figured doing so might be helpful to end users, but in practice I have found it to be anything but for most people. I inject a quick registry change to show those pesky extensions .

bios.bootdelay = 20000