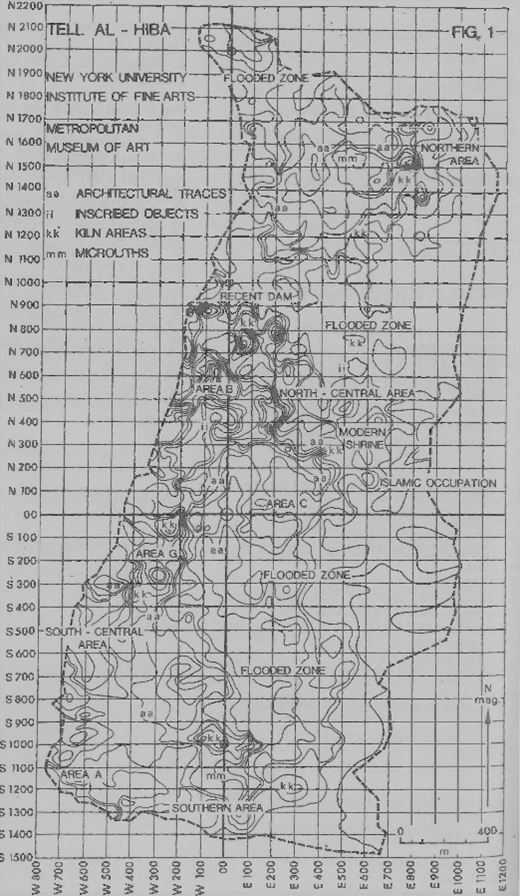

Legacy Exploration

Archaeological exploration at Tell al-Hiba dates back to the late nineteenth century. Between March 29 and May 11 1887, a German expedition under the direction of Robert Koldewey excavated three separate areas around the highest part of the site, exposing large public buildings and part of a residential sector. At the end of his six week season, he concluded that the mound was a large necropolis that had experienced extensive burning.

Robert Koldeway (1885 – 1925)

Photo from “Koldewey at Babylon”

World Archaeology Issue 57 Jan 25, 2014

Photo of Area C from the north al Hiba archive

Until the middle of the 20th century, scholars thought that the site of Telloh, 25 km to the north, was ancient Lagash because of the monumental architecture, sculpture and other works of art as well as thousands of cuneiform documents that contained references to the cities of Girsu, Lagash and Nigin. In 1953, the site was inspected during a survey of the area by Thorkild Jacobsen (1904 – 1993) and Fuad Safar. On the surface of the mound an inscription was found, making it was possible for Jacobsen to confidently identify Tell al Hiba as ancient Lagash, and to associate the ancient name of Girsu with the modern site of Telloh.

Thorkild Jacobsen at Tell Asmar in 1931/31.

Photo from Alchetron June 29, 2018.

Fuad Safar (1911 – 1978) Iraqi archaeologist.

Photo from Iraq 40 (1978): 1.

© The British Institute for the Study of Iraq

NYU/Metropolitan Museum of Art Excavations 1968 – 1990

Lagash was first scientifically investigated during five seasons beginning in 1968 and ending in 1978 by a joint project of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU under the leadership of the Director and Permit Holder Dr. Vaughn Crawford (MMA) and Field Director Prof. Donald P. Hansen (NYU) and Deputy Director Prof. Edward Ochsenschlager (CUNY Queens). This five year campaign was brought to an end by the Iran-Iraq war.

Vaughn E. Crawford joined the department of Ancient Near Eastern Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1957, serving as curator in charge from 1973-1981. He served as Project Director for the Excavations at al Hiba/Lagash from 1969 to 1978. He held his PhD in Sumerian from the University of Chicago. He made great friends in the village of Al Hiba, and to this day, they remember his kind and generous character.

Vaughn E. Crawford joined the department of Ancient Near Eastern Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1957, serving as curator in charge from 1973-1981. He served as Project Director for the Excavations at al Hiba/Lagash from 1969 to 1978. He held his PhD in Sumerian from the University of Chicago. He made great friends in the village of Al Hiba, and to this day, they remember his kind and generous character.

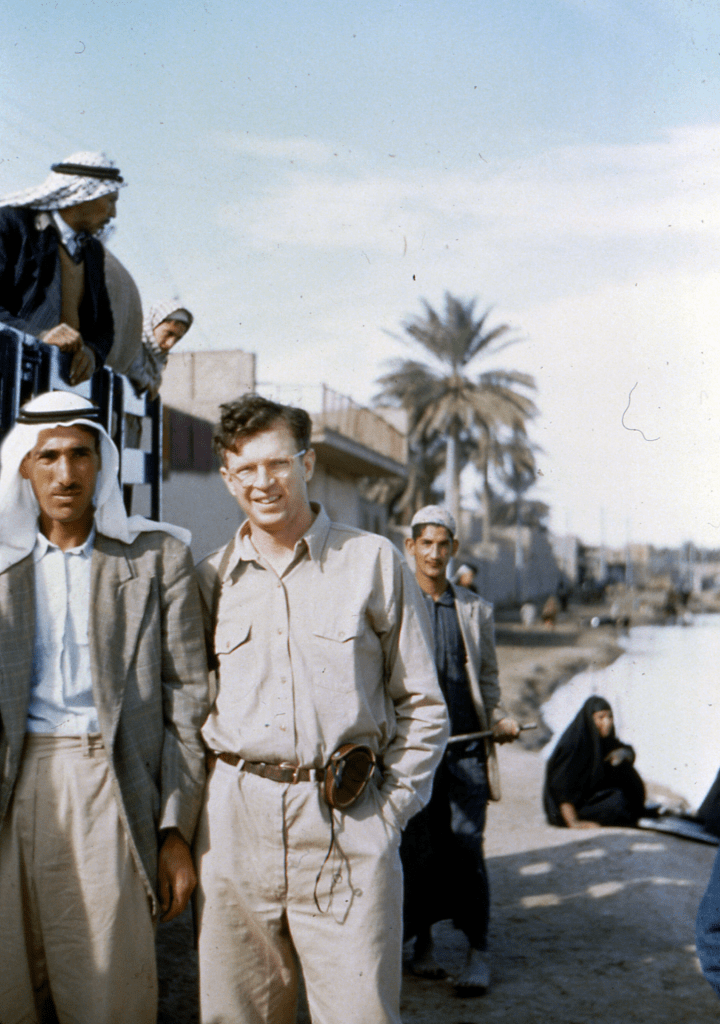

Dr. Donald P. Hansen (1931-2007) was the Craig Hugh Smyth Professor of Near Eastern art and archaeology at the Institute of Fine Arts and New York University. In 1968 he joined with the Metropolitan Museum of Art to launch excavations at the site of al Hiba, ancient Lagash. Seen here at the edge of the marsh in the 1968 season.

Dr. Donald P. Hansen (1931-2007) was the Craig Hugh Smyth Professor of Near Eastern art and archaeology at the Institute of Fine Arts and New York University. In 1968 he joined with the Metropolitan Museum of Art to launch excavations at the site of al Hiba, ancient Lagash. Seen here at the edge of the marsh in the 1968 season.

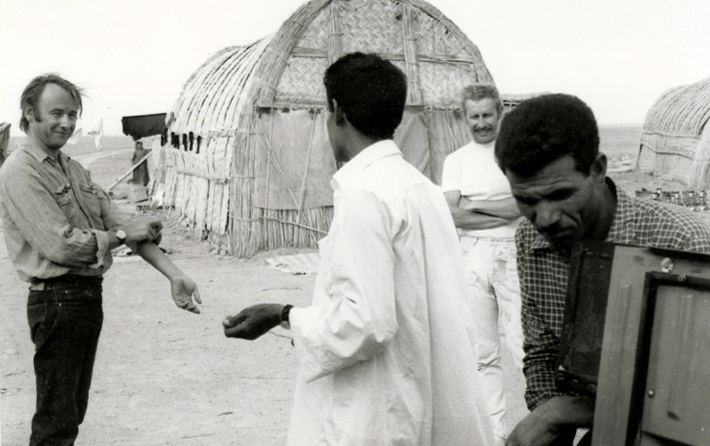

Donald Hansen and Edward Ochsenschlager (in the white tee shirt) talking with villagers working on the expedition. Behind them is one of the three large mudhif’s that served as living and working quarters for seasons between 1968 and 1978.

Donald Hansen and Edward Ochsenschlager (in the white tee shirt) talking with villagers working on the expedition. Behind them is one of the three large mudhif’s that served as living and working quarters for seasons between 1968 and 1978.

Edward Ochsenschlager, Professor emeritus of Queens College, New York City served as the ceramicist for the expedition developing a typology and recording more than 80,000 sherds in secure archaeological context. Ochsenschlager also undertook ethnographic study during his time at Hiba, writing Iraq’s Marsh Arabs in the Garden of Eden (University of Pennsylvania Press 2005).

Edward Ochsenschlager, Professor emeritus of Queens College, New York City served as the ceramicist for the expedition developing a typology and recording more than 80,000 sherds in secure archaeological context. Ochsenschlager also undertook ethnographic study during his time at Hiba, writing Iraq’s Marsh Arabs in the Garden of Eden (University of Pennsylvania Press 2005).

Iraq’s Marsh Arabs in the Garden of Eden by Prof. Edward Ochsenschlager (University of Pennsylvania Press 2005).

Iraq’s Marsh Arabs in the Garden of Eden by Prof. Edward Ochsenschlager (University of Pennsylvania Press 2005).

In 1984, Prof. Elizabeth Carter (UCLA) lead a small team to survey the site determining that the period of greatest occupation was the Early Dynastic III period (2500-2350 BCE).

Results of the NYU/Met Excavations

An analysis of Carter’s survey results undertaken by the final publication project revealed differential concentrations of ceramics from Early Dynastic I-III Period, together with activity areas with high concentrations of burning and slag.

Those six campaigns revealed monumental and administrative architecture, which was explored in four areas of the mound.

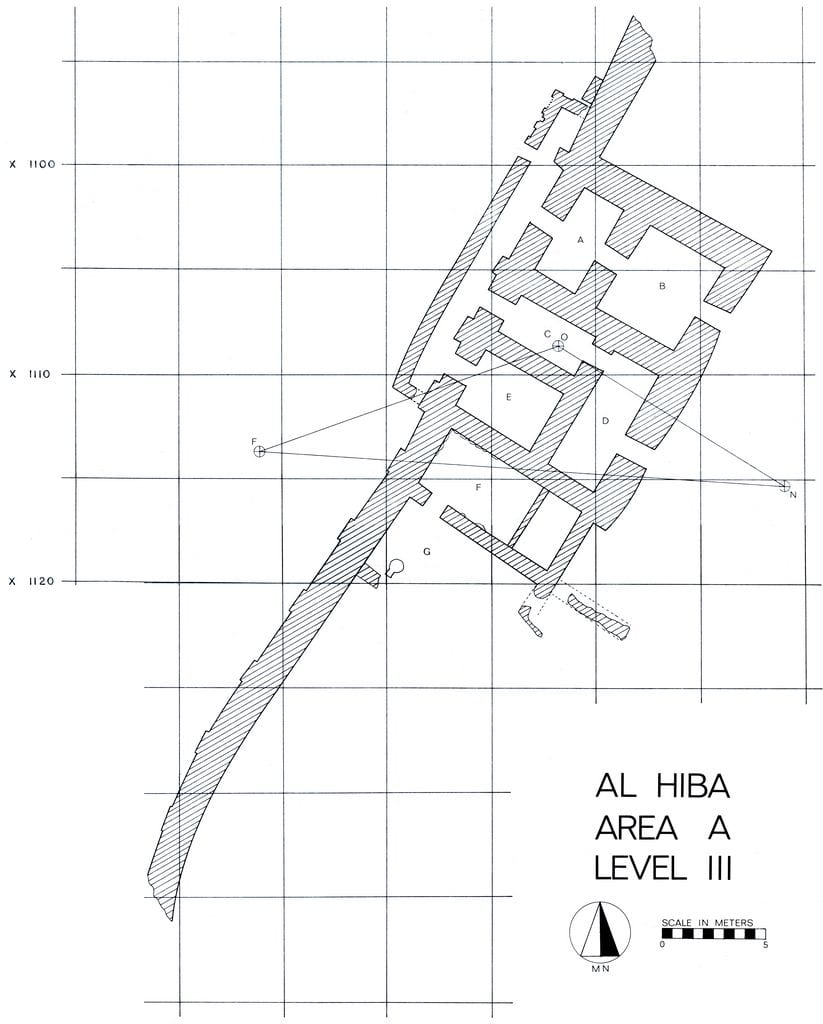

Area A: Ibgal of Inanna

Excavation in Area A, located at the southwest corner of the site, began in 1968 and lasted until the very beginning of the third season. Hansen’s work here uncovered three building levels of the Ibgal, a temple oval dedicated to Inanna. A sounding dug from the earliest level of the temple, Level 3, reached the water table. In it, the excavators identified nine building levels. Based on the pottery, all nine levels are Early Dynastic with the lowest level dating to an early phase of ED I.

Ibgal of Inanna level 3

Level 3 was only partially excavated, but the architectural remains included a niched-and-buttressed wall with three doorways. Two of these led indirectly into the interior of the complex while the third provided access to an isolated room. Based on parallels with Level 1, these doorways were likely the main entrance to the structure.

Left: The Ibgal of Inanna Level 3 Area A.

Ibgal of Inanna Level 2

The Level 2 building was largely destroyed by the construction of the Level 1 temple. As a result, little is known of Level 2 except its layout. The recovery of a niched-and-buttressed wall may indicate that the excavators uncovered the southern edge of this complex.

The Level 2 building was largely destroyed by the construction of the Level 1 temple. As a result, little is known of Level 2 except its layout. The recovery of a niched-and-buttressed wall may indicate that the excavators uncovered the southern edge of this complex.

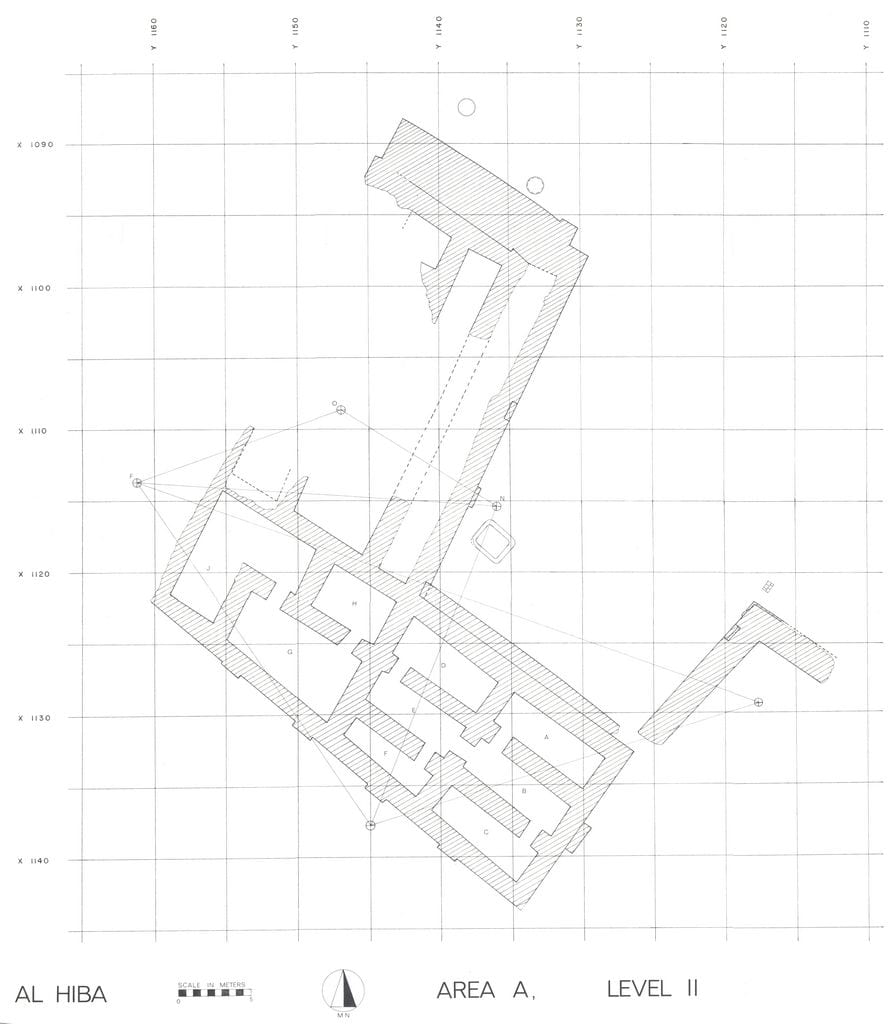

Left: The Ibgal of Inanna Level 2 Area A.

Ibgal of Inanna Level 1

Level 1, the topmost building level, dates to the reign of Enanatum I, whose foundation deposites were found incorporated into the lowest layers of brickwork. Erosion had almost entirely destroyed the living spaces of the building, leaving only the substructure. The Level 1 foundations consisted of thick walls enclosing variously-sized rectangular spaces. Broken pieces of alluvial mud and layers of sand filled these spaces and they were capped by one or more courses of mud brick at or near the tops of the walls. The end result was a platform that appeared solid, but actually contained a network of filled cavities, all underlain by a layer of sand.

Level 1, the topmost building level, dates to the reign of Enanatum I, whose foundation deposites were found incorporated into the lowest layers of brickwork. Erosion had almost entirely destroyed the living spaces of the building, leaving only the substructure. The Level 1 foundations consisted of thick walls enclosing variously-sized rectangular spaces. Broken pieces of alluvial mud and layers of sand filled these spaces and they were capped by one or more courses of mud brick at or near the tops of the walls. The end result was a platform that appeared solid, but actually contained a network of filled cavities, all underlain by a layer of sand.

Above: Plan of Ibgal of Inanna Level 1 Area A.

The relationship between the network of spaces in the foundations and the now vanished superstructure is unclear. Dr. Hansen suggested that the layout of the filled spaces within the platform may have corresponded to the layout of the buildings built upon it.

Area B: Bagara of Ningirsu

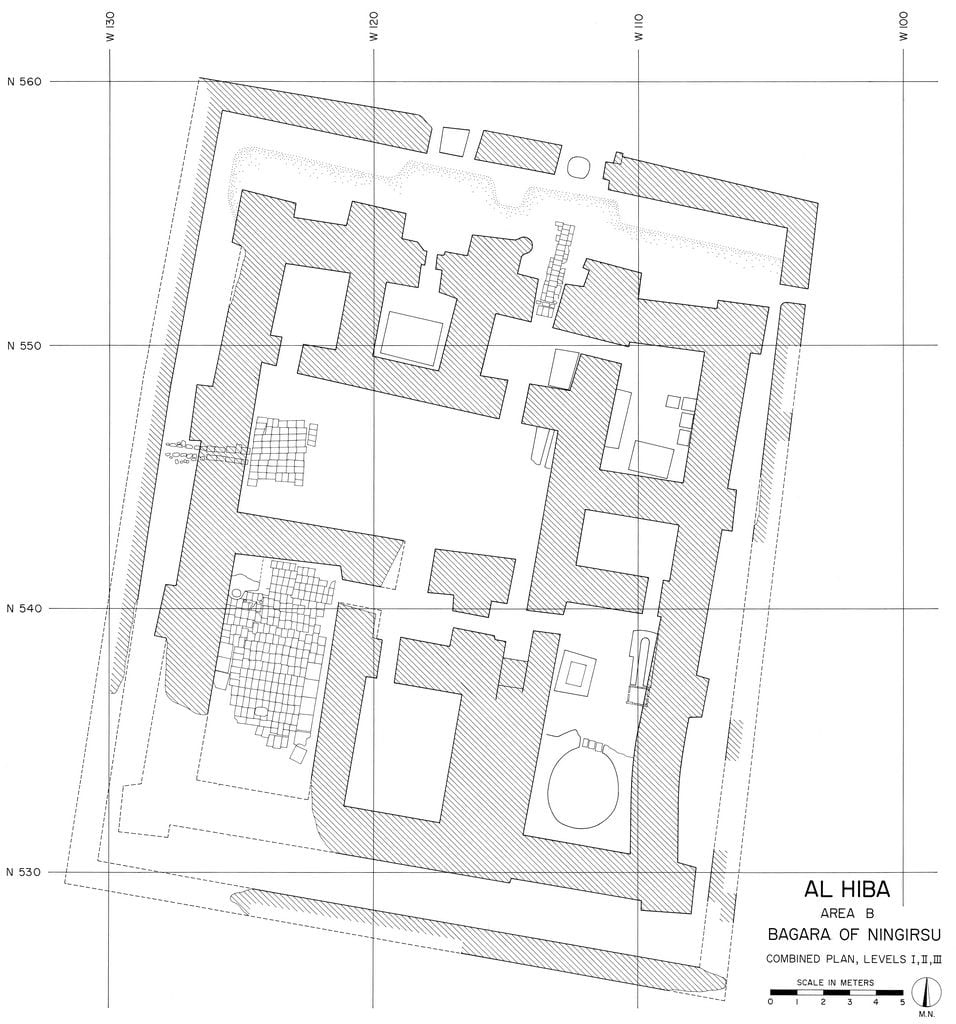

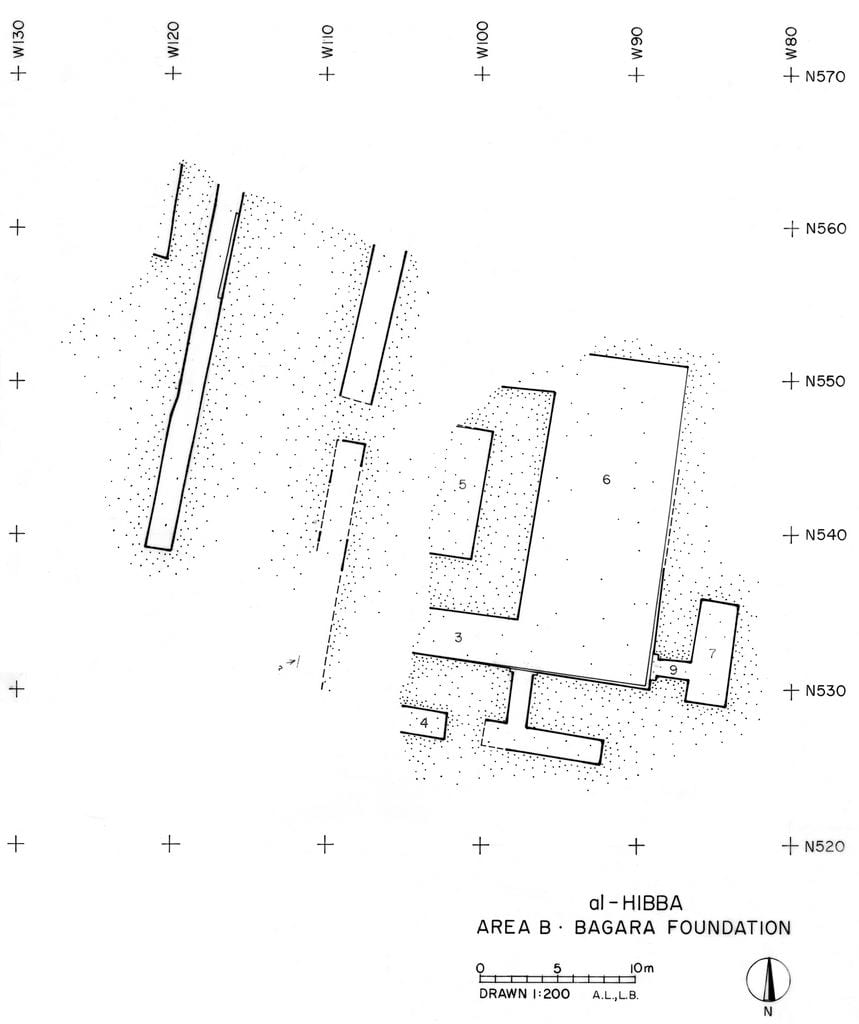

Area B is located roughly 1500 m northeast of Area A. In this zone, the expedition partially uncovered the Early Dynastic III and Isin-Larsa/Old Babylonian remains of a temple complex known as the Bagara of Ningirsu, the head of the Lagash state pantheon.

The Early Dynastic III remains consisted of two adjacent buildings. The western building was a niched-and-buttressed structure within a low enclosure wall. Near the entrance to the building was a bent-axis room with a podium. The finds within this building included multiple inscribed stone bowls, maceheads, and seal impressions. An inscribed dagger from the earliest excavated level bore the name of Eanatum, the third ruler of the Lagash I dynasty.

The Early Dynastic III remains consisted of two adjacent buildings. The western building was a niched-and-buttressed structure within a low enclosure wall. Near the entrance to the building was a bent-axis room with a podium. The finds within this building included multiple inscribed stone bowls, maceheads, and seal impressions. An inscribed dagger from the earliest excavated level bore the name of Eanatum, the third ruler of the Lagash I dynasty.

Left: Composite plan of Bagara of Ningirsu ED III West Building Area B.

On the basis of its size and the presence of multiple ovens in the rooms of the complex, Dr. Hansen suggested that this structure was a temple kitchen dedicated to servicing the needs of the main shrine of Ningirsu, located elsewhere in the Bagara Complex.

On the basis of its size and the presence of multiple ovens in the rooms of the complex, Dr. Hansen suggested that this structure was a temple kitchen dedicated to servicing the needs of the main shrine of Ningirsu, located elsewhere in the Bagara Complex.

To the east, the project exposed three levels of another building with a large oven, baked-brick basin, and many ceramic vats. Fragments of Gudea-period building were preserved above. The excavators interpreted this structure as a brewery. Above: Main Oven in Brewery Bagara in Ningirsu Area B.

Above the Early Dynastic III remains were the baked-brick foundations of the Isin-Larsa/Old Babylonian version of the temple. These construction of these foundations had removed all but a little of architecture in the area that post-dated the Early Dynastic III period. Due to erosion, almost none of the architecture from the “living” levels of the complex were preserved.

Above the Early Dynastic III remains were the baked-brick foundations of the Isin-Larsa/Old Babylonian version of the temple. These construction of these foundations had removed all but a little of architecture in the area that post-dated the Early Dynastic III period. Due to erosion, almost none of the architecture from the “living” levels of the complex were preserved.

Left: Isin-Larsa OB Foundations Area B

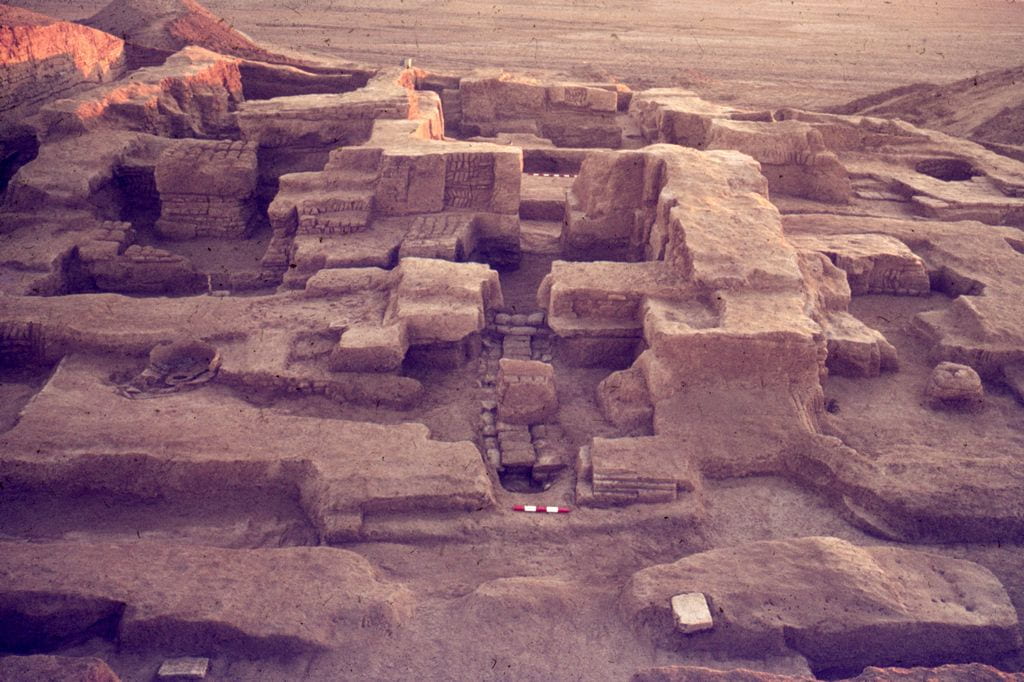

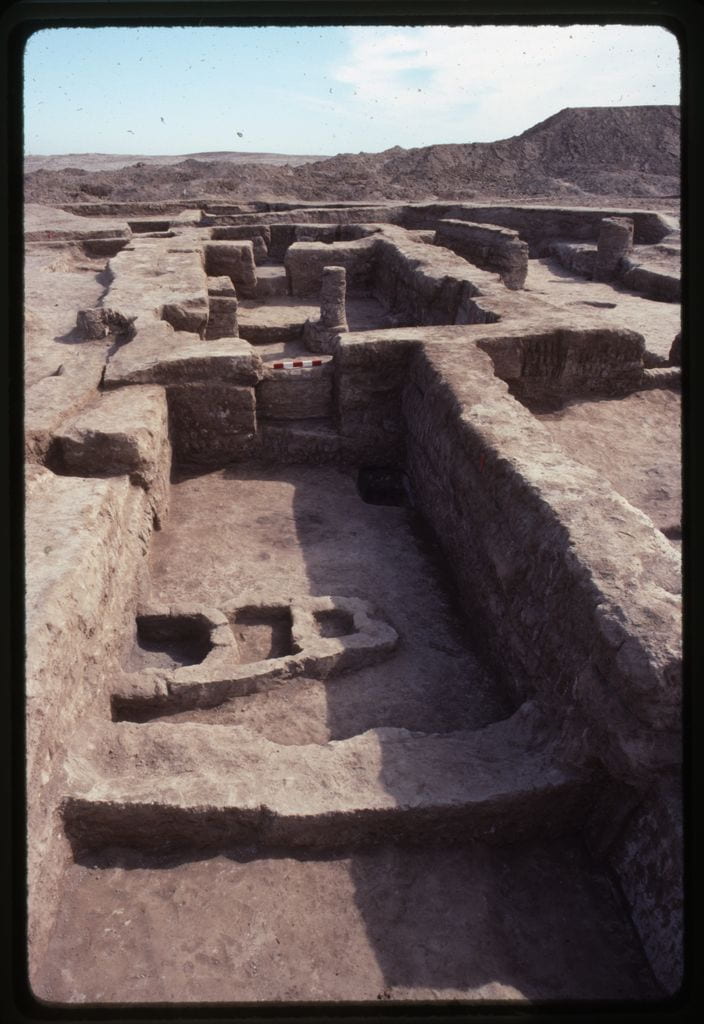

Area C

Excavation in Area C, located 360 m southeast of Area B, occurred entirely during the second second. The excavators were first drawn to the area due to the visibility of burned plano-convex brick on the mound’s surface. Althought they initially expected to find tombs, they instead exposed a large complex of rooms with a surface area of around 1000 m that dates to ED IIIB. Two building levels, IA and IB, were uncovered. During Level IB, the building developed in an agglutinative manner that resulted in warrens of rooms in a variety of sizes. Rather than regularize the building in Level IA, the builders largely preserved the layout of Level IB in their reconstruction.

Excavation in Area C, located 360 m southeast of Area B, occurred entirely during the second second. The excavators were first drawn to the area due to the visibility of burned plano-convex brick on the mound’s surface. Althought they initially expected to find tombs, they instead exposed a large complex of rooms with a surface area of around 1000 m that dates to ED IIIB. Two building levels, IA and IB, were uncovered. During Level IB, the building developed in an agglutinative manner that resulted in warrens of rooms in a variety of sizes. Rather than regularize the building in Level IA, the builders largely preserved the layout of Level IB in their reconstruction.

Above: Brick Arch in Level IA Area C.

This complex contained a large number of seal impressions and tablets. In Level IB, seal impressions and tablets signal activity during the reigns of Eanatum, Enanatum I, and Enmetena. Level IA has less conclusive evidence, but it likely dates from the reign of Enmetena and his immediate successors.

This complex contained a large number of seal impressions and tablets. In Level IB, seal impressions and tablets signal activity during the reigns of Eanatum, Enanatum I, and Enmetena. Level IA has less conclusive evidence, but it likely dates from the reign of Enmetena and his immediate successors.

Left: View of East End of Complex Area C.

Metal Hoard in Level IA Area C

In their preliminary report, the excavators suggested that this complex may have had an administrative function. Dr. Zainab Bahrani later analyzed the structure for her dissertation. She concluded that the complex may have been a craft workshop with different sectors devoted to metalworking, wool processing, reedworking, and possibly scribal education.

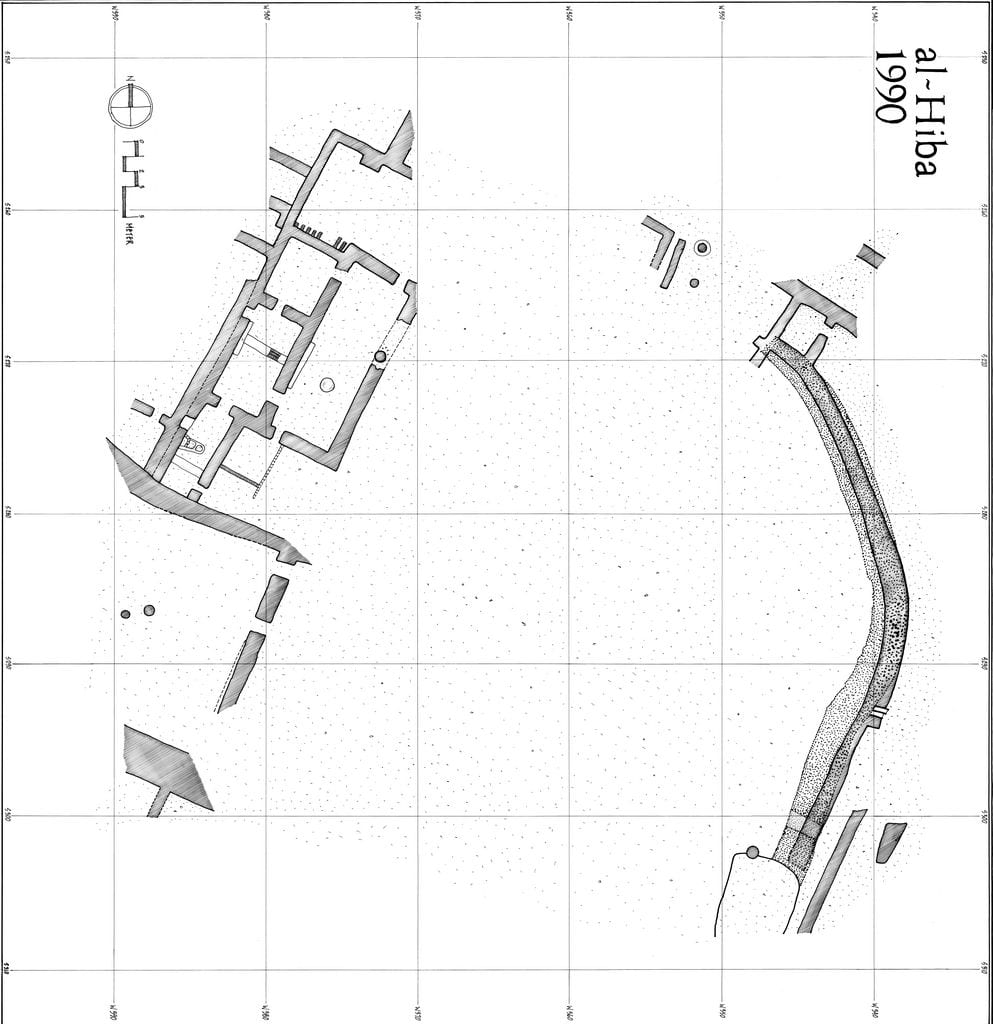

Area G

Area G is located around 800 m southwest of Area B along the western edge of the mound. The expedition spent three season (3H, 4H, and 6H) in this area, where they uncovered extensive ED I deposits. The work focused on two zones separated by about 20 m. The architecture in these two areas was never connected archaeologically.

Area G is located around 800 m southwest of Area B along the western edge of the mound. The expedition spent three season (3H, 4H, and 6H) in this area, where they uncovered extensive ED I deposits. The work focused on two zones separated by about 20 m. The architecture in these two areas was never connected archaeologically.

Left: Composite Plan of Area G Architecture Area G

During 3H and 4H, work occurred in the east zone. The whole area had been cut by pits, intrusive vertical drains, and later burials, but the levels from which these came had eroded away. Beneath the surface, the excavators uncovered a 2 m-wide north-south running wall that curved towards the northwest. This wall was set upon a foundation and had drains at the base of it. Along the east side, a smaller complex of rooms was exposed, which persisted through multiple building levels. A sounding conducted in 4H extended down to the water level and exposed 7 m of ED I deposits.

During 3H and 4H, work occurred in the east zone. The whole area had been cut by pits, intrusive vertical drains, and later burials, but the levels from which these came had eroded away. Beneath the surface, the excavators uncovered a 2 m-wide north-south running wall that curved towards the northwest. This wall was set upon a foundation and had drains at the base of it. Along the east side, a smaller complex of rooms was exposed, which persisted through multiple building levels. A sounding conducted in 4H extended down to the water level and exposed 7 m of ED I deposits.

Above: West Complex, Looking Southwest Area G.

In 6H, the 2 m-wide wall was traced further north and a complex of rooms was uncovered in a zone to the west. At the northern end of the curving wall, a smattering of architecture, including a small room, was exposed. Further west, the excavators dug more extensively. In the western complex, they uncovered 5 building levels (BL A—D). The earliest level (BL A) was only exposed in a few small areas, so little is known about it. Starting with BL B, the general form of the complex was set and would remain similar for the rest of the building levels. The complex was rebuilt in BL C, but some dividing walls were removed in order to create a number of larger spaces. During BL D, a large courtyard was built on the southern end. The north and east sides of the courtyard were bounded by two thick brick walls. The northern wall cut through some of the BL C walls and rested upon a foundation that was similar to that seen in the curving wall in the eastern section. Despite the disruption caused by the construction of the southern courtyard, the rooms to the north continued to be used at this time. Finally, BL E is badly preserved due to erosion, but the parts identified suggest that the complex retained a similar layout to that seen in BL D.

In 6H, the 2 m-wide wall was traced further north and a complex of rooms was uncovered in a zone to the west. At the northern end of the curving wall, a smattering of architecture, including a small room, was exposed. Further west, the excavators dug more extensively. In the western complex, they uncovered 5 building levels (BL A—D). The earliest level (BL A) was only exposed in a few small areas, so little is known about it. Starting with BL B, the general form of the complex was set and would remain similar for the rest of the building levels. The complex was rebuilt in BL C, but some dividing walls were removed in order to create a number of larger spaces. During BL D, a large courtyard was built on the southern end. The north and east sides of the courtyard were bounded by two thick brick walls. The northern wall cut through some of the BL C walls and rested upon a foundation that was similar to that seen in the curving wall in the eastern section. Despite the disruption caused by the construction of the southern courtyard, the rooms to the north continued to be used at this time. Finally, BL E is badly preserved due to erosion, but the parts identified suggest that the complex retained a similar layout to that seen in BL D.

Above: View of West Complex, Looking North Area G.

Excavating the seal impressions Area G

The nature of the remains exposed in Area G are unclear. Their size suggests an institutional affiliation. The material culture found within does not provide much insight. However, seal impressions recovered in BL B and BL C indicate a connection between the complex and access to goods controlled by an administrative authority.

Hansen presented the results of his in preliminary reports and one unpublished doctoral dissertation. When Hansen died in 2007, Dr. Pittman inherited the archive and proceeded to digitize all of the records and systematically study and publish the results of his work. Graduate students participated in this process and the final publication project is now in the last stages of completion. The results will be presented in three volumes of the Aratta series published by Brepols.

The first volume to appear, in October 2021, is the study of the pottery from the Hansen excavations undertaken by Dr. Steve Renette. This new analysis provides an analysis that takes into account more than 80,000 sherds recorded in archaeological context from the Fourth and Third Millennia BCE.

Dr. Darren Ashby completed his dissertation on the temples of Area A and B in 2017, and he is preparing this study for publication. Two further volumes of architecture and archaeology of Areas G and C are near completion. Work on those has been undertaken by Prof. Pittman together with Drs. Ashby, Renette and Giacomo Benati. Marc Marin Webb has contributed the analysis of the architecture of Area C and Area G. Bringing the publication of these legacy excavations to a close provided the impetus to begin a second campaign with new research goals building on past results.