Courtrooms are places of striking contrasts. The stern formality of the law, the stark walls of the buildings, the austere attire of the officers of the law – everything gestures towards predictability, formality, and cynicism. Yet what frequently unfolds in these steely courtrooms are tales of tenderness, love, unpredictability, passion and much more. Be it a criminal or a civil case, such contrasts erupt with a regularity that is neither surprising nor unexpected.

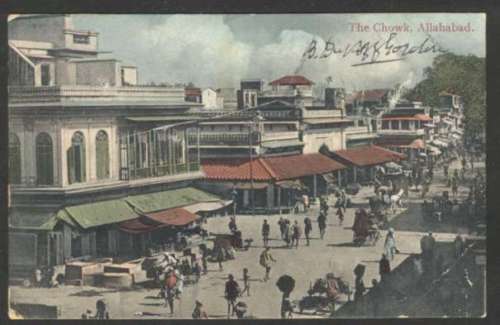

But it is doubtful that the Allahabad Small Causes Court had appeared as anything but a drab tomb to Mr W. Church. An ambitious Eurasian, like so many others of his class, Mr Church found few avenues open to him for upward mobility in Victorian India. A product of the imperial system who were seen by the British overlords to be both an useful labour pool and an embarrassment, the Eurasians were pigeonholed into the lowest echelons of the colonial clerkdom. Whilst the Eurasians were certainly not alone in being pigeonholed as the clerks of the empire, unlike other similar groups – such as say, the Bengali Hindus – the Eurasians did not have access to a society outside the state where they could achieve status and respectability. Indeed, most of the “Indian” clerks, coming as they often did from relatively higher-caste groups, used their clerical connections to supplement their already high social status within their communities. Moreover, many of the latter would work their way up the clerical ladder and then be given titles such as “Rai Bahadur” or “Khan Bahadur” which further contributed to their social status. None of this was available to the Eurasians. Yet culturally, they were encouraged to think of themselves as better than their “Indian” neighbors and akin to their British overlords. The combination of these dynamics produced a curious situation where the ambitions and the actual possibilities open to a Eurasian man were almost orthogonal to each other. Mr Church was a case in point. He was a Court Clerk at the Small Causes Court in Allahabad in the 1870s, but aspired to much greater and grander things none of which were actually within his reach.

Mr Church had married another Eurasian like himself. Indeed, the match, by the intricate systems of Eurasian social hierarchies of the day, was an excellent one since the young Mrs Church’s father was a full-blooded Briton. The British father-in-law, however, had long departed back to the land of his forefathers leaving behind his Eurasian wife and mixed-race daughter. Though he conscientiously continued to send enough money to keep his wife and daughter in relative comfort in the Eurasian settlement at Chunar, he was for all intents and purposes a distant and absent figure in the family. Yet his European identity stood his daughter in good stead and it might well have been the reason the ambitious Mr Church married her in 1873.

The marriage, unfortunately, lasted less than two years. Sometime in the year 1875, Mr Church, tired of his clerical existence, stole the money in the Court treasury that he was responsible for and absconded without saying a word to his wife. Mrs Church, after the shame and ignominy of the ensuing publicity had abated, returned to live with her mother in Chunar upon the money sent by her British father.

Chunar then was far from the dusty gangland it is today. A small cantonment town with a large concentration of Eurasians, it was a well-appointed little community where Eurasians felt at home. Many an Eurasian family chose to move there, away from the hustle of the larger cities of Allahabad, Kanpur and even Calcutta, to live amongst themselves in quiet respectability. Mrs Church, once she returned to her mother, was placed uncomfortably on the fringes of this quiet respectability. Neither married nor divorced, she was stuck in a strange limbo with even fewer options than her desperate husband had had. Years gradually passed by and Mrs Church began to dreadfully countenance a lifetime of loneliness. Her only comfort was that the society at Chunar was a lively one. The Eurasian community throughout Hindustan was known for its love of parties, balls and soirees, and Chunar was no exception. Gradually, Mrs Church began to immerse herself in the social life of her home town. It was thus that she came to be one of the subscribers of a ball in 1879.

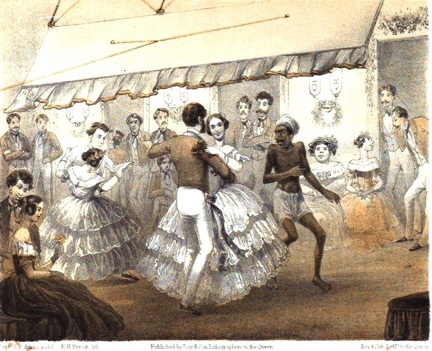

At the ball, the Civil Surgeon of Chunar invited a friend of his, Sheikh Nur Muhammad. Mr Muhammad held a senior clerical position in the Octroi Department, but like many of his class and unlike the Mr Churches of the day, he was also a rich landowner. In fact, Mr Muhammad was the owner of five villages in the pargana of Athgawan in Benares district. Most people respectfully referred to him as Tehsildar Sahib. The clerical job supplemented Mr Muhammad’s income and gave him access to the privileges accruing from association with the state, but it did not define him or his social station the way it had for Mr Church. Aside from his circumstances, Mr Muhammad was a handsome and dashing, if already aging, gentleman. At the ball he danced gracefully but with a flair, and charmed many a young lady. Amongst the latter was Mrs Church. Though she did not dance with him, she recalled years later how she had been impressed by his dancing. Happily for both of them, a common friend introduced the two before the evening was out. Mrs Church could not help her heart beating just a tad faster as she shook the hand of the gallant Tehsildar Sahib.

It was barely a week since the ball when the Tehsildar Sahib called upon Mrs Church and her mother. A man of great refinement and charm, he pleased mother and daughter equally well. Mrs Church’s mother even invited him back before he departed. The Tehsildar Sahib was only too keen to accept the invitation and soon he became a regular visitor in the house. Love blossomed with the breathlessness of sprouts sown too late in the spring. Mrs Church soon found herself, by her own admission, ardently praying to her Lord, Jesus Christ, to make the Tehsildar Sahib fall in love with her. Unbeknownst to her, the flame burnt equally brightly in the old Tehsildar’s heart. The latter, however, remained taciturn, if charming, for months before he made his move. Then one day, upon realizing that Mrs Church’s mother was out, the Tehsildar Sahib made so bold as to walk straight into Mrs Church’s room without having himself announced. This minor indiscretion was, of course, a serious breach of etiquette, but Mrs Church was already too deeply in love to notice. The shrewd suitor, however, had intended the breach as a deliberate test of where he stood and, needless to say, was happy with the results. That his breach had not angered the lady told him all he wished to know. The next day, he returned. And this time, following etiquette, he paid his compliments to the mother, before seeking out Mrs Church on the veranda. It was late afternoon in October, 1879, and the shadows had already begun to lengthen. The doves sat cooing in their coves as the last rays of the setting sun withdrew from the courtyard. The whitewashed walls were now a patchwork of shadows and light. And it was in that checkered world of white and black, that the dashing old Tehsildar popped the question to the still beautiful but not-so-young Mrs Church.

Her Lord had heard her prayers. Mrs Church was delighted beyond all measure and immediately accepted without waiting for her mother’s approval. Overwhelmed with joy and grateful for being saved from the slow but inexorable descent into old age and penury, she asked if there was anything at all that she could do to make her future-husband happy. The grand old lover, with all his grace and reticence suggested that she might give up the European fashion of dress in favour of the Muslim attire. Naturally, Mrs Church was only too happy to oblige.

But of course, not everything went as smoothly. For starters, Mrs Church’s mother, though she was very well-disposed towards Mr Muhammad, did not approve of the old Muslim gentleman as her son-in-law. There was also the issue of the absconding Mr Church. After many enquiries it transpired that though he had not kept in touch, he was still alive and well. Moreover, a marriage such as the present one evoked very strong feelings in the small and conservative Eurasian community at Chunar. After months of trying thus, the bride and groom decided to move the wedding to the more cosmopolitan Benares.

Early in 1880, Mrs Church left her mother’s home and arrived at the house of one Mr Inayet Hussain in Benares. She was accompanied on her journey from Chunar to Benares by Ashraf Hussain, a son of Mr Muhammad’s through a previous marriage, and an ayah. Inayet Hussain was a colleague of Mr Muhammad’s in the Octroi Department and his closest friend. It was decided that he would act as Mrs Church’s guardian till the wedding. It was at Mr Hussain’s house that Mrs Church embraced Islam and changed her name to Mehar-un-nisa. She also adopted the purdah at this stage and happily confined herself to the zenana, appearing no longer to any other man but Mr Hussain and his son, Sabt Ahmed. About 15 days after this, she was married by a Kazi to Mr Muhammad and moved into his house in Benares. Sabt Ahmed and another friend of Mr Hussain’s acted as the necessary witnesses to the nikah.

By all accounts, Mehar-un-nisa’s married life was a short but happy one. Nur Muhammad died sometime in 1887 but he left Mehar-un-nisa with substantial landed property and an young son, Kabir-ud-din. Her stepson, Ashraf, remained on good terms with her and continued to transact business relating to the ancestral lands jointly. The absconding Mr Church too had passed away in 1886. Mehar-un-nisa’s father passed away four years later in 1890.

In early 1891, a legal challenge by Ashraf’s mother, Gauhar-un-nisa, and another ex-wife of Nur Muhammad, Umdat-un-nisa, along with their respective daughters, Aziza and Hafiza, attempted to have Mehar-un-nisa’s marriage and inheritance annulled. Despite winning the case at the lower court on the grounds that the marriage had violated some of the finer details of the Islamic marriage law regulating marriages between married converts and Muslims, the challengers eventually lost the case at the High Court. The Allahabad High Court held that the long and happy domesticity between Mehar-un-nisa and Nur Muhammad clearly proved that everyone concerned had accepted the marriage as valid at the time. They also thus recognized Kabir-ud-din as Nur Muhammad’s legal heir. Ashraf supported his stepmother’s claim throughout. Eventually, the family settled out of court and divided the property equally amongst the three wives.

Nur Muhammad and Mehar-un-nisa’s marriage was hardly made in heaven. Yet there was something incredibly romantic and hopeful about it. Muhammad’s two earlier marriages, going by circumstantial details, were the kind of carefully calibrated, socially respectable marriages that were the norm in elite Indian landholding families. Love had very little to do with such marriages. For a man like Muhammad, himself caught between the two worlds of the Ashrafi adab of Awadh and the Anglo-Indian culture of the Raj bureaucracy, such marriages possibly did little more than provide legal heirs to inherit the ancestral lands. Neither Gauhar-un-nisa nor Umdat-un-nisa would likely have been impressed, as Mehar-un-nisa was, with Nur’s waltzing skills. The entire world of Anglophone culture, its dances, its literatures, its etiquette, and above all, its romance which Nur had imbibed in the course of his professional life yawned like an abyss between him and the world of Athgawan pargana that he had left behind. Likewise, Mehar’s earlier life as Mrs Church had left her with neither love nor money. The heavily constricted world of Eurasian respectability, already impoverished of choices, had narrowed further for her with her first husband’s embezzlement and disappearance. The money her British father sent her mother was literally the only thing standing between her and utter penury. In other words, neither Nur nor Mehar had too many choices or chances of finding happiness and companionship.

That they found each other and were able to have a life together, for no matter how short a time, I feel, saved them both. Ill-matched in age, wealth, and of course, faith, they were the couple that was not supposed to be. And yet, they were. They lived happily and had a child. Nur, in his last years knew the companionate marriage and conjugal love that had eluded him all his life and Mehar found both the love and financial security that had been out of her reach earlier. Their impossible love story was one of those footnotes to the Empire. It was a love story that would not have happened had the exigencies of British imperial power not brought together the daughter of a British soldier and son of an Awadhi landlord at a ball in Chunar.

Though we do not hear of Mehar-un-nisa any further after 1891, chances are she lived out her old age happily as a Muslim lady of rank in the polite society of Benares. But one wonders about young Kabir. Did he ever think of his forever-absent British grandfather? Did he learn to waltz like his father? Or did he, like so many young, aristocratic Muslims from Awadh, attend the Aligarh Muslim College and join the Muslim League?

hallo website thanks to its exposure to truly benefit all.

People of Kolkata are enriched with cultural information,This is the another example.Cheers,Keep doing such a nice work.