Rachel D. Goldstein, W’22

A place where textbooks filled with cocaine are delivered, a building where students coordinated the kidnapping of their peers, a location of an arson attack: All three can be found at a single site on the University of Pennsylvania’s campus, the Psi Upsilon fraternity house. As seen by fall 2021 protests outside this building, colloquially called the “Castle,” Psi Upsilon’s home has become an unintentional monument to the University administration’s (un)willingness to discipline fraternities on campus. As detailed in this report, the University seems to favor a certain kind of student body—wealthy, well-connected, racially diverse—represented by Psi Upsilon.

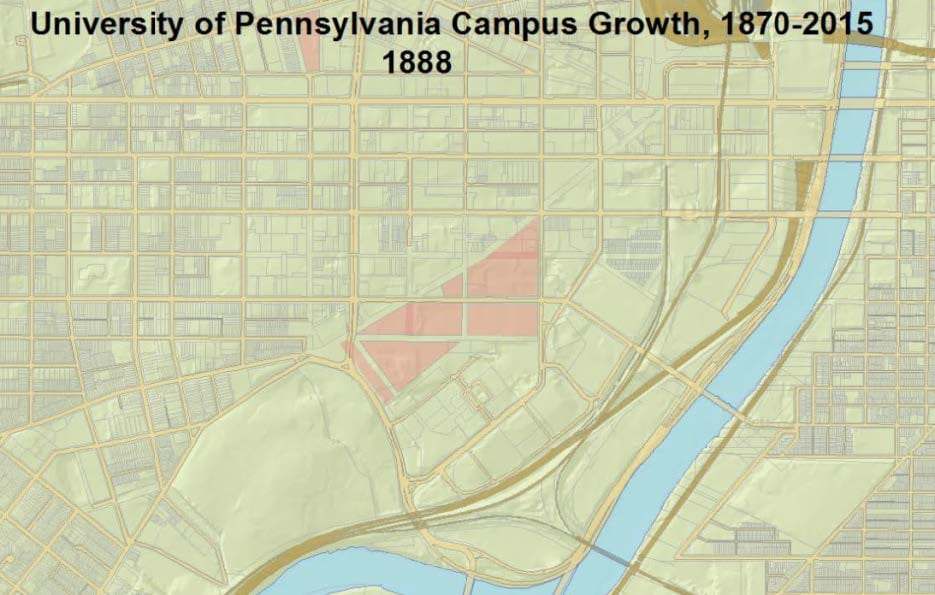

Since its construction, the events taking place within Psi Upsilon have reflected the values of administrators at the University of Pennsylvania. In the late nineteenth century, the University valued established academics and men’s betterment through education. In 1888, the Psi Upsilon fraternity bought the land where an old Y.M.C.A. building had stood at intersection of 36th and Locust and Woodland Ave (College Notes, 1890). To replace this community center, the fraternity began a $30,000 building project, which involved taking down the entire Y.M.C.A facility. From here, Philadelphia architects Hewitt & Hewitt designed “the first building to be built as a fraternity in the United States” (Geldon, 1998). The exterior is made of limestone and was donated by a Psi Upsilon brother Joseph Price.

The interior of the house, which has always been hidden not only to local Philadelphia residents but also to most the University’s student body, did not remain empty for long. Within a month of the renovation’s completion in 1890, Psi Upsilon fraternity members began to host social gatherings (Daily Pennsylvanian, 1890). The first of these events was a reception and housewarming party hosted by the wives of Psi Upsilon members. The party welcomed Charles Dudley Warner, noted author and friend of Mark Twain, to the fraternity house, which opened to all University of Pennsylvania students, who at the time were all male (Daily Pennsylvanian, 1890). Although the event was organized and “graciously hosted by member’s wives,” there is no reference to women being allowed to attend the event. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Castle continued to host authors, politicians, and athletes, and house the male members of the organization (Confident, 1918). As the University’s goal at the time was to educate men, the space that Psi Upsilon occupied and its practices were a direct reflection of this aspiration.

Today, the Castle’s superior location at the center of campus, compared to all other student houses, is part of what makes it so notable. However, during the Great Depression, the house’s location was no more desirable than that of any other fraternity. In the 1930s, Locust Walk did not exist, and the building was located across from “a big area of asphalt,” where students would “rush and dodge automobiles and trolley cars” (Morris, 1928). During this era, there are no references in the Daily Pennsylvanian to Castle’s location being preferable to other fraternities. As Locust Walk developed over the 20th century to become the center of campus life, however, the space occupied by Castle became more coveted.

The University’s ability and willingness to control fraternities at various points in the twentieth century is reflected through their interactions with Castle. During, World War II, the Dean of the Office of Student Affairs asked civilian students in fraternities to vacate their houses. This policy included Psi Upsilon, alongside thirty other fraternities (Daily Pennsylvanian, 1942). This instance marks the first time in the fifty years since this building’s completion that the Psi Upsilon chapter would not be inhabited by its members. It also marks one of the few times where the University was able and willing to truly regulate and influence the behavior of fraternity members.

The University’s control over fraternity’s and overall ability to influence these groups diminished rapidly over the second half of the twentieth century. One reason the influence of the University diminished is likely due to the increased amount of students participating in Greek life on campus. In 1946, when Psi Upsilon members moved back into the house, all fraternities on campus experienced staggering amounts of new pledges (Daily Pennsylvanian, 1946). In 1951, the first reference of women from sororities being invited into Psi Upsilon was described. Although women had been able to attend the University’s College of Liberal Arts for Women since 1933, there were no references in the Daily Pennsylvanian archives of women being invited to fraternity house parties until after 1950. Clearly, the presence and participation in Greek life had grown beyond men to women by the 1950s, which likely only increased the influence that Greek life had on campus, and the inability of the University to regulate their behavior. In 1951, Psi Upsilon was one of “thirty-one houses that exhibited an excellent spirit of cooperation by participating in this all-University function [fraternity beer parties]” as it invited female co-eds into their house for Ivy Week (Daily Pennsylvanian, 1951).

During the 1950s, the University’s first unsuccessful attempt to monitor the behavior of fraternities on campus occurred. The University administrators enacted a “social probation at the beginning of the year because of scholastic difficulties” on Psi Upsilon and six other fraternities (Daily Pennsylvanian, 1956). Although the Daily Pennsylvanian wrote extensively about the athletic programs of these fraternities, it is not until this article in the late 1950s that academics are mentioned in relation to fraternities. Therefore, one can assume, that the purpose of these fraternities for the first half of the 20th century, was primarily as a social and athletic club. Further, it is likely that the University was not particularly focused on the athletic performance of the fraternities during the World Wars and Great Depression.

When the University has challenging social and economic issues, it chooses not to regulate the fraternities. For instance, after the 1950s, the University returned to its previous practice of not regulating the fraternities. This can be seen as there are few references to Psi Upsilon from 1960 through the late 1970s, or any other fraternity in the Daily Pennsylvanian Archives, beyond reporting of their sports scores. This is likely due to the newspaper’s focus on more salacious and dramatic events like the Cold War, race relations, and economic tumult since the fraternities, regardless of their persistent rowdy behavior, were not being disciplined.

The University’s willingness to regulate fraternities shifted moderately in the 1980s. This is likely because the nature of the fraternities’ misconduct had become illegal in the court of law, rather than offensive to the students or faculty. A Daily Pennsylvanian article described the presence of “dealers and heavy users” on campus as well as the fact that “if there is one drug being abused on campus, it’s coke” (Gladstone, 1981). The article also described “a flurry of drug busts on campus in recent months one of which occurred this spring at Psi Upsilon fraternity” (Gladstone, 1981). The University, likely due to the legal ramifications of this misconduct, attempted to police these fraternities. Their lackluster punishment, “an administrative warning for drug cases” resulted in Psi Upsilon showing “no efforts to participate in a drug awareness workshop, required by the board last May” (Liu, 1982). The University’s disregard for the rule-breaking lasted, even as the notoriety of these scandals mounted. For instance, Castle’s drug abuse continued in 1985 when “cocaine was packaged in hollowed-out books and sent to the Psi Upsilon fraternity. The cocaine in this instance was not recovered” (Lane, 1987).

The most dramatic incident came in 1987, when Alexander Moskovitz, a Wharton senior, was arrested and indicted on “on 13 drug-related counts, including charges that he masterminded two major shipments of cocaine to the University” (Lane, 1987). The University did not punish Castle for this incident, even when the police gleaned new evidence from this arrest which helped explain “the 1985 discovery of a cocaine package at the Psi Upsilon fraternity” (Lane, 1987). The University believed the brothers alleged story that when they realized that the package was a “hollowed-out Spanish reference book containing 350 grams of cocaine, with a street value of approximately $200,000,” that before they could report the incident to the police, “Moskovitz came into the house inquiring about the shipment” (Lane, 1987). The University also believed students when they stated that Moskovitz “offered them $5,000 to give him the box” but that they refused this offer (Lane, 1987). The cocaine from this shipment was never recovered. Further, the University believed the brothers account of Moskovitz going “into a tirade, threatening the lives of the brothers and the safety of the house” and “threatening to ‘smoke the house’ if he was not given the drugs,” without any proof beyond the members’ stories (Lane, 1987). Even when the fraternity brothers admitted to giving Moskovitz the package, the University conducted no follow-up investigation or punishment for this action. Perhaps because following Moskovitz’s departure, the brothers called the police, the University found their actions redeemable. Although the police later determined that “the tactic of transporting cocaine in hollowed-out books” meant that someone in Castle had likely been buying drugs from Moskovitz, Penn did not sanction the fraternity (Lane, 1987). The University expelled Moskovitz when he was arrested but did not punish any of the members of Castle, a group which is known for being particularly wealthy and well-connected. The University’s unwillingness to punish Psi Upsilon student reflects their laissez-faire approach to certain members of the student body. The Moskovitz incident clearly suggests a University priority of maintaining enrollment of wealthy, well-connected students.

Even as it turned a blind eye to privileged students, the University worked to increase student diversity on campus. In 1988, Castle members served on a diversity committee, “Blacks at Penn,” a group that was looking to address the “hot issue” of increasing Black representation (Mitchell, 1988). Castle was unique at the time for the racial diversity found in its membership, a fact that remains true. At this panel, Castle advocated for diminishing the differences between Black and white Greek organizations, since both organizations could take members of either race should they choose to (Jackson, 1988). Beyond its preference towards wealthy and well-connected students, the University has and continues to value diversity. The Castle, which from the 1980s through today has embodied all three of these values, is in alignment with all University’s goals.

Regardless of their common aims, the University could not turn a blind eye to the actions of the Psi Upsilon members forever. On January 19, 1990, University officials and Public Safety officers began “investigating a bizarre incident involving Delta Psi and Psi Upsilon brothers last weekend in which one fraternity member was abducted” (Hilk, 1990). During this incident, “several brothers from Psi Upsilon abducted a brother from Delta Psi, holding him for an unknown amount of time” in an act of “retaliation for a dispute which arose during a Castle party” (Hilk, 1990). I spoke with current members of Psi Upsilon and was readily informed that “the guy abducted had called one of our brothers the n-word the night before” (Goldstein, 2021). A later Daily Pennsylvanian article noted, “Despite the racial remarks that were allegedly made to the victim, the incident is not being investigated as racially motivated” (Lutton, 1990). One unnamed University student during the 1990 incident stated that the rivalry between Saint A’s and Castle “originally started off as traditional fraternity rivalry, however, as one fraternity changed, the other didn’t. By change I mean diversify. It all sort of erupted into chaos with the racial incidents that happened at A’s … It added a new dimension to the rivalry” (Lutton, 1990).

When the University moved to punish the “fraternity brother and a pledge who were arrested on charges of kidnapping,” it attempted to spread the punishment across multiple members of the fraternity. As a punishment for “allegedly blindfolding the victim, putting a bag over his head, and taking him to an unknown area to handcuff the victim to a tree” and “playing tapes of Malcolm X speeches to the victim” as well as calling “him anti-Semitic and racist,” all 27 active members of the Castle were charged with “collective responsibility” by Constance Goodman of the inter-fraternity judiciary committee. The brothers were no longer allowed to live in their house (Lutton, 1990). The University’s penchant for protecting Psi Upsilon was not entirely gone, however. Goodman advised the Castle to “keep a low profile and not have parties until this incident is resolved” (Lutton, 1990).

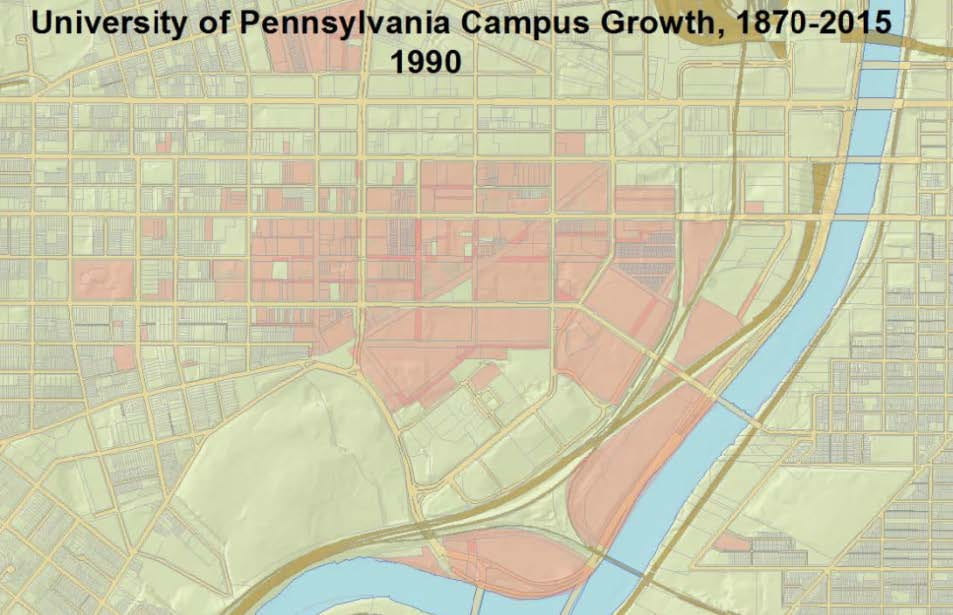

President Sheldon Hackney’s decision to suspend Psi Upsilon seems to have been part of a goal of “diversifying the main artery of student housing on campus” (Jung, 1990). Students at the time of Castle’s removal questioned the University’s change in stance towards disciplining fraternities. Theta Xi fraternity President Ed Pedicone said, “It seems like the Castle’s being suspended has happened at a convenient time for the University to address the whole diversification issue,” and “I hope [diversification] didn’t have anything to do with the decision, but I really can’t be the judge” (Jung, 1990). Previously, when Locust Walk was not as central to Campus, the University did not care as much about Castle and likely even found some of their goals pertaining to advancing diversity to be admirable. In fact, one administrator said “this particular fraternity has undertaken with particular effort to diversify, and I think that is important” (Jung, 1990).

Although the University temporarily removed the brothers, the administration’s ability to socially renovate Locust Walk was stymied by previous legal agreements. In 1951, had signed an agreement that “the University owns and controls the property under the condition that it is used as a residence;” however, “the Psi Upsilon graduate chapter has “reversionary” rights” (Lutton, 1990). This means that “the house will revert to alumni control if the conditions of the agreement are violated,” so “if the University uses the building as office space, control of the chapter would be given to the alumni” (Lutton, 1990). Essentially, the University had to keep the building as a dorm, and must continue to do this to maintain ownership. In 1990, the University’s Assistant General Counsel Steve Poskanzer described the lease agreement as “an unusual reversionary agreement,” and added that “the agreement does not talk about what happens if they get kicked off campus because it was not written with that in mind” (Lutton, 1990). This legal agreement shows that the University had been largely disinterested in controlling the fraternities in previous decades.

Part of the reason the University was so slow to refill the house relates to issues presented by Psi Upsilon’s alumni. Although the University owns seven of the ten Greek houses in the center of campus, “the administration does not have free rein with any of the properties, even ones that it legally owns” because “when the fraternities turned over the houses to the University years ago, they each set legal stipulations that strictly define and limit the University’s power over them” (Culbertson, 1990). Clearly, the University was not prepared or ever expecting to have to regulate these fraternities.

With these challenges present, the house remained empty for the entirety of the 1990–91 academic year, even as several student groups vied for the “must luxurious spot to live on campus” to belong to their group (Jung, 1990). Finally, “after several protests by student groups who said that the fraternity-dominated composition fostered racist and sexist sentiment along the walk,” the University announced that only a “non-fraternity or sorority group of students will move into the former Psi Upsilon fraternity house” (Jung, 1990). This decision was widely unpopular, and sorority leaders wrote to the Daily Pennsylvanian to say “putting women on the Walk would be a major step towards diversification” (Patel, 1990). Further, many students and administrators at the time of the announcement felt that the University was making the lack of diversity on campus worse. Hackney said, “Unfortunately we have just kicked the most diverse group on Locust Walk off campus” (Ochs, 1990). It is clear that in the 1990s, Castle had defined itself through the diversity of its membership, that was not apparent in its fraternity neighbors.

Even in 1990, Castle had become “the symbol in debate over the Walk” and “a microcosm of the whole diversity on the Walk issue” (Culbertson and Patel, 1990). Student perception of the suspension of Castle and their removal from their home was largely mixed. Andrew Teagle, a University undergraduate wrote that “everyone forget[s] why they were kicked off? They aren’t complete and utter meanies. There are a lot worse around here. They just screwed up and got caught” (Teagle, 1990). In this way, Castle became an unintentional monument once again as “some students saw Psi Upsilon’s eviction as a way to begin diversification,” while other students saw the administration’s “delaying the process of filling the spacious building” as “reflecting the University’s sluggishness in addressing diversity on the Walk” and went so far as to describe the president as “neglectful” (Culbertson and Patel, 1990).

The University’s goals were once again reflected in the group they chose to eventually fill the house. Finally, after a year of the building being vacant, “President Sheldon Hackney announced that a Community Service Program will fill the former fraternity house” that was “dedicated to service to the wider community” (Patel, 1991). One goal of the new house was to “strengthen the University’s ties with the West Philadelphia community” as “the new program will provide a formal center and could serve as a rallying point for students interested in community service” (Patel, 1991). Although, in the same statement Hackney announced that “when Psi Upsilon is allowed to come back, we expect they will be able to reclaim what is rightfully theirs” and that the community service program was only allowed to live there on “a temporary basis” (Patel, 1991). Students felt that Hackney’s actions to diversify Locust Walk were insufficient and “a group of faculty, staff and students formed a coalition which petitioned Hackney to act more aggressively in putting student residences on the Walk and evicting fraternities who do not behave” (Culbertson, 1992).

While the University had been interested in replacing the residents of Castle with a tangible symbol of their philanthropic goals, it did not go so far as to prevent Castle members from acting as they pleased, so long as it was not in the house. During the legal fights over the house, the brothers of Castle had formed a “secret” off campus fraternity known as the Owl Society, or more colloquially as “Owls” (Lutton, 1991). The name “Owls” was chosen as the Psi Upsilon symbol is an owl and the logo for “Owls” is an owl with one eye open, rather than the two eyes open that Psi Upsilon’s logo has (Goldstein, 2021). Additionally, “Owls” was “comprised primarily of former Psi U members” (Lutton, 1991). In 1995, “the Inter-fraternity Council granted conditional recognition to the Psi Upsilon fraternity” as the committee was impressed with “some very good positive ideas in the agreement they presented to us especially with academics and philanthropy” and wanted “a strong national fraternity with strong alumni backing” (Feigenbaum, 1995). Also, during this meeting, it was shared that in 1950, “the fraternity and the University entered into an agreement in which ownership of the property was given to the University;” however, “the agreement said that if Psi Upsilon ever lost its house, the University would have to provide the fraternity with another property and pay for moving costs” (Feigenbaum, 1995) The article continued to describe the agreement’s specificity as it detailed the potential new spaces on Locust Walk that the fraternity could choose the for the University of “build and pay for a new structure to be erected” for the brothers (Feigenbaum, 1995). Clearly the financial implications of permanently removing the Psi Upsilon brothers from their Castle were not pleasing to the University. Further, the presence, and thriving nature of Castle during the entire probationary period, under the new name “Owls” shows the University’s removal of Castle was largely performative and more for their own goals, rather than out of a desire to regulate the behavior of wealthy, well-connected students.

The University’s attempt to regulate the fraternity brothers was largely unsuccessful, as there is nothing in the house today to show a change in members’ behaviors. Upon reinstatement, a “Psi Upsilon consultant said he was working to organize the new chapter by building a core group of prospective members man by man instead of accepting an entire group” (Marcisz, 1995). Regardless, when the Psi Upsilon brothers were able to return to their Castle in 1998, “displacing Penn’s community service residential program,” the brothers placed “a stuffed deer’s head and elk’s head” in the living room and dining room, both of which remain present in the house today (Lucey, 1998). The brothers claimed that their “biggest accomplishment was surviving the 2.5-year process to get back on campus” and how they were thankful to “Chapter alumni” who were “contributing financially” and “helping the brothers refurnish the house, which the University had renovated substantially in 1991, shortly before the community-service program moved in” (Lucey, 1998). These renovations cost the University over $500,000 (Lucey, 1998). Aside from the brief time when members could not throw parties in the house, the regulations that the University imposed on Psi Upsilon members had very positive implications for the members.

The University has not attempted to regulate Psi Upsilon to such an extent ever again. From 1998, until the 2010s, there are no reports of misconduct or suspensions by Psi Upsilon members. Rather, Psi Upsilon’s exterior and interior were featured in multiple movies, including Kimberly and Transformers: 2. In 2015, the Castle was back in the spotlight as an “Owls” brother lit a fire on the Psi Upsilon house (Nickey, 2015). No one was hurt and the fire was quickly extinguished. The student was asked to leave the University, but not expelled; he was able to graduate from Georgetown University. Once again, the University showed its prowess for enacting different standards for wealthy, well-connected students, which members of both Castle and “Owls” almost universally are.

The most recent instance of the University not disciplining fraternities was inspiration for this paper. In September, 2021, the Daily Pennsylvanian wrote of an “alleged assault of a Penn sophomore” at the Psi Upsilon house (Daily Pennsylvanian, 2021). The alleged incident resulted in a series of protests outside of Psi Upsilon and a petition with approximately 1,000 signatures for the University to evict Castle. As of December 2021, the University has not made a single statement about the event, and the Daily Pennsylvanian editorial board wrote that the University’s lack of response “allows Castle to operate with impunity” (Daily Pennsylvanian, 2021).

The reluctance to share the investigation process of this incident has enraged many students and been seen by many as the University’s way of protecting wealthy students. Psi Upsilon briefly stopped hosting parties, much like in 1985, but has recently resumed their normal activities, with University provided registered door managers, which shows the University’s acknowledgement of these functions (Goldstein, 2021). Castle has once again become an emblem of the University’s lack of transparency and inaction regarding disciplining students.

After spending three and a half years at Penn, I believe that a similar history could be told of many other fraternities on Locust Walk. The findings in this report suggest that Castle members are not solely to blame for their reckless behavior, because decades of non-regulation have led to a sense of impunity. Episodes of ineffective punishment have reinforced that sense. This report has shown that the University prioritizes certain kinds of students, and is willing to take unconventional, even irrational approaches, to protect them.

Bibliography

“Army And Civilians to Move into University Dormitories.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 14 Sept. 1944, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Binder, Gary. “Two Frats Placed On Probation By U.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 24 Oct. 1979, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

“College Notes.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 9 Oct. 1890, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu

Confident. “NAVAL MEN ASSIGNED TEMPORARY QUARTERS.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 9 Oct. 1891, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Culbertson, Emily. “Ownership Not Final Word in Frat Debate.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 9 Nov. 1990, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Culbertson, Emily, and Roxanne Patel. “Castle House Has Become the Symbol in Debate over the Walk.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 7 Dec. 1990, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Culbertson, Emily. “The Daily Pennsylvanian, Volume CVIII, Number 62, 30 June 1992.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 30 June 1992, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

“Fraternity Leaders Urge Cooperation in Relief Contributions.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 7 Apr. 1936, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Feigenbaum, Randi. “IFC Approves Reinstatement of Psi Upsilon Future of the Castle Still unclear4.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 15 Mar. 1995, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Geldon, Ben. “The Night the Castle Crumbled.” The Daily Pennsylvanian, The Daily Pennsylvanian, 9 May 2019, https://www.thedp.com/article/1998/04/the_night_the_castle_crumbled.

“Greek Beer Parties.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 3 May 1951, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Hilk, Matthew. “U., Public Safety Investigate Alleged Frat Kidnapping.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 25 Jan. 1990, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Jackson, Olita. “In the Bond.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 3 Mar. 1988, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Jung, Helen. “U. To Decide Fate of Frat House.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 3 May 1990, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Jung, Helen. “Psi U Next Steps.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 14 May 1990, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

LaMonica, Paul. “Psi U. Will Reapply for Recognition Frat Could Return next Fall.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 26 Oct. 1993, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Lane, Randall. “4 Pounds of Cocaine Found in U. Mailroom Package Addressed to Frat, Romance Languages.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 14 Apr. 1987, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu

Lane, Randall. “Coke Shipment Tied to Earlier Activities.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 17 Apr. 1987, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu

Lane, Randall. “$1 Million Coke Shipment Discovered at U.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 1 July 1987, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu

Lane, Randall. “Campus Cocaine Kingpin Indicted by Grand Jury Student Held in Million-Dollar Shipments to Williams Hall, Castle.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 30 July 1987, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Lane, Randall. “Dealer’s Arrest Sheds Light on ’85 Cocaine Delivery to Fraternity.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 30 July 1987, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Liu, Nina. “Sigma Nu Probation May End Advisory Board Cites Improvement.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 23 Apr. 1982, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/

Lucey, Catherine. “Once Again, Psi Upsilon’s Home Is Its Castle.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 1 Oct. 1998, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Lutton, Christine. “Castle Charter Revoked Frat to Vacate House Monday.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 3 May 1990, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Lutton, Christine. “Judge Blocks Castle Punishment.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 11 May 1990, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Lutton, Christine. “Psi U Nat’l Pushes Ban on ‘Owl’ Group.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 2 Apr. 1991, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Marcisz, Chris. “Psi Upsilon May Return to Castle.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 3 Nov. 1995, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Meszaros, Jack. “Frats.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 30 Jan. 1975, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Mitchell, Brent. “Briefs.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 5 Feb. 1988, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Morris. “A Park, with No Parking.” Daily Pennsylvanian , https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Nickey, Lowell Neumann. “Updated: Student Arrested in Castle Arson Investigation.” The Daily Pennsylvanian, 29 Oct. 2015, https://www.thedp.com/article/2015/10/student-arrested-in- connection-to-castle-arson.

Ochs, Stephen. “Pres.: Castle to House Non-Frat Group.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 10 Sept. 1990, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu

Patel, Roxanne. “Castle Will Become Living-Learning House Program Will Focus on Community Service.” The Daily Pennsylvanian 28 February 1991 – Daily Pennsylvanian Digital Archives, 28 Feb. 1991, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Patel, Roxanne. “Sorority Unlikely to Live in Castle.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 12 Sept. 1990, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Patel, Roxanne. “Hackney Says Frats on Walk Won’t Be Moved Pres, Officially Charges Committee.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 20 Sept. 1990, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu

“Probation Ends for Six Houses.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 22 Feb. 1956, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

“PSI UPSILON RECEPTIONS.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 27 Nov. 1890. “Rushing Is Back to Pre-War Status.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 17 Apr. 1946, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu

Siegel, Richard. “British Student Spends Year Here As I-F Guest.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 20 Nov, 1957, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

Teagle, Andrew. “In Which We Say Goodbye.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 14 Apr. 1990, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

The Daily Pennsylvanian Editorial Board. “Editorial: Castle Must Be Held Accountable.” The Daily Pennsylvanian, The Daily Pennsylvanian, 2 Oct. 2021, https://www.thedp.com/article/2021/09/upenn-castle-fraternity-assault-greek-life-editorial.

“Two Castle Members Charged with Kidnapping St. A’s Brother.” Daily Pennsylvanian, 14 Feb. 1990, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu/.

“University War Chest.” Daily Pennsylvanian , 31 Dec. 1942, https://dparchives.library.upenn.edu