Zack J. Leder, C’22

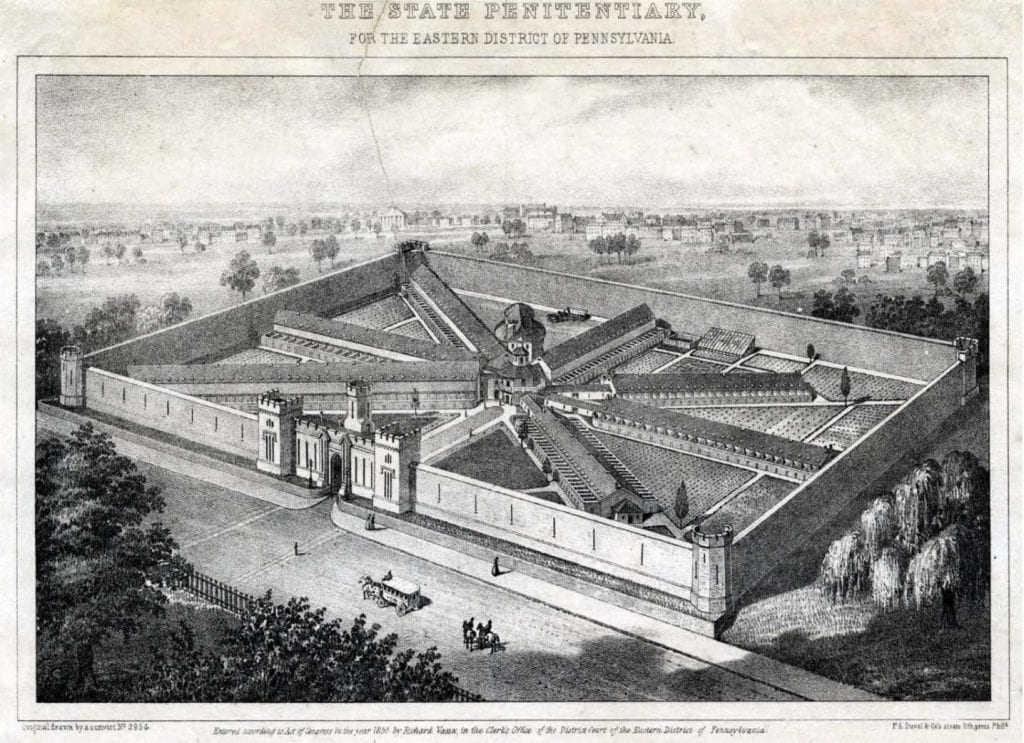

Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary opened in what is now Philadelphia’s Fairmount neighborhood in 1829 and was known as the world’s first true “penitentiary” [1]. In 1821, prison reformers convinced the Pennsylvania Legislature that an isolated site northwest of the city (now Fairmount) would be perfect for the new prison. They believed that building the prison on elevated land away from the polluted industrial center of the city would allow for good airflow, and in turn make healthier prisoners [2]. Designed by John Haviland in “hub and spoke” architecture style, it inspired prison architecture and management around the world thereafter. Eastern State was the first prison to instill the “Pennsylvania model” of imprisonment, where prisoners were subjected to 24 hours of solitary confinement. This then-revolutionary method was designed to mentally break prisoners and inspire true regret in their hearts, instead of punishing them, which was previously believed to be most effective. This mode of imprisonment, first tested at Eastern State, was referenced in famous social theorist Michel Foucault’s 1975 book, Discipline and Punish, as one of the most influential developments in the carceral state [3]. Eastern State once held (in)famous individuals like “Slick Willie” Sutton and Al Capone, but its true historical value comes from its architecture and its significance to the modern penal system.

Once the world’s most expensive and well-known prison, Eastern State was abandoned in 1971, a year after closing [4]. In the decade and a half following abandonment, the grounds became dilapidated and completely deserted. An urban jungle grew within the cell blocks, and the prisoners were replaced by stray cats and crumbling walls [5]. Seeing almost no value in the historic prison, the city was ready to sell Eastern State’s eleven-acre plot to the highest bidder.

This article analyzes the period between 1971 and 1994, when this historical prison went from being a neglected block to a nationally recognized monument. The prison was saved and turned into a museum by a rag-tag group of architects, preservationists and historians known as the Eastern State Task Force. Although the museum now makes measured efforts to “interpret the legacy of American criminal justice reform, from the nation’s founding through to the present day,” [6] this article argues that the very individuals who saved the prison advocated on behalf of the interests of a privileged few and did not consider what could benefit the community as a whole when determining urban renewal plans. This speaks volumes about the city of Philadelphia and its relationship with the intersection of urban renewal, crime, politics, and city finances.

Even though Philadelphia was and still is a city with one of the highest incarceration rates in the nation, the city prioritized financing historic preservation over neighborhood interests. This reinforced the elitist “color-blind” preservation tactics exhibited through Philadelphia’s urban renewal in the postwar era, the effects of which can still be felt today [7]. The people who worked to keep Eastern State alive to preserve it as a historic site made no efforts to incorporate the thoughts and wishes of neither the former prisoners nor the local Fairmount neighborhood residents, many of whom were former prisoners themselves.

Historian Seth C. Bruggeman explains how Philadelphia in particular has an interesting relationship with incarceration:

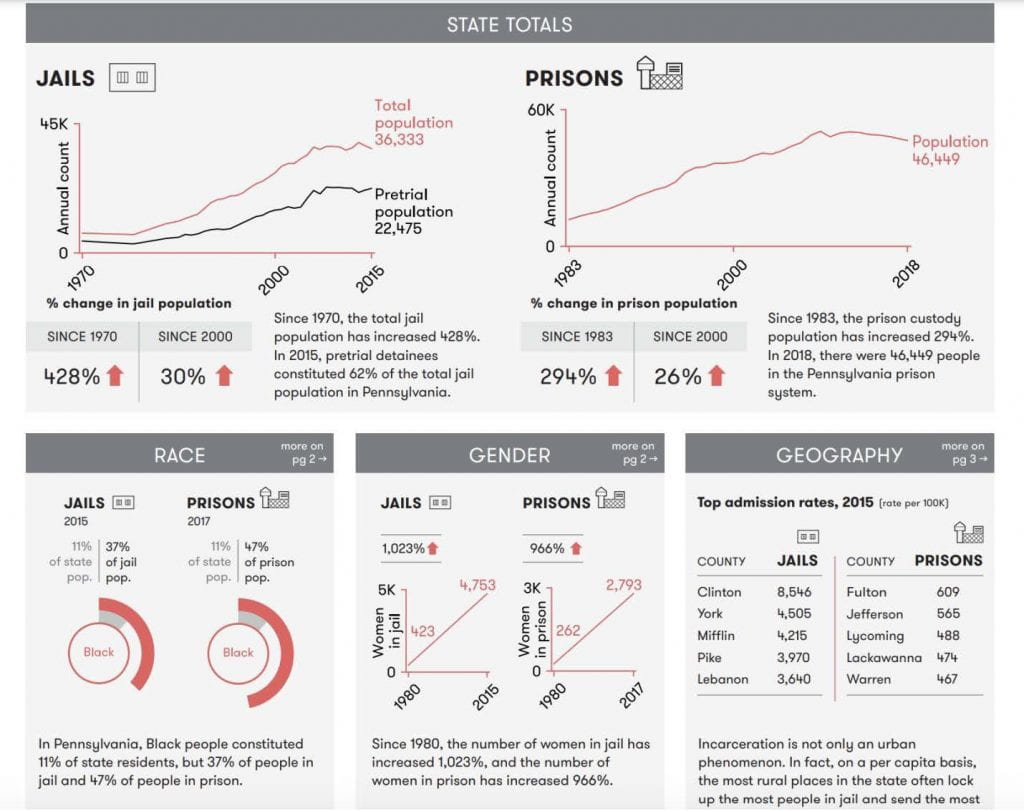

Pennsylvania’s inmate population outpaces all other states’ and owes considerably to Philadelphia’s consistently high crime rates. In fact, as of 2006, Philadelphia had the highest incarceration rate of all US cities… Of all prison museums, then, Eastern State is perhaps the most perfectly positioned to help its community make sense of the astonishing impact that mass incarceration has had on urban spaces in recent decades. And yet so far its efforts to do that have largely failed [8].

This failure that Bruggeman is alluding to can be attributed to the Eastern State Task Force. As Ronald Reagan “D.A.R.E.”d to declare a war on drugs, and as the nation took a deep carceral turn in the 1980s, these individuals were more focused on finding donors to support the creation of a carceral museum than figuring out ways to address incarceration through a museum.

Bruggeman and others point out how various separate moving parts led to Eastern State’s transition from prison to monument. Following World War II, the Fairmount area lost a large percentage of its white population to developed urban centers downtown or mainline suburbs. Real estate developers wanted to cash in on old industrial neighborhoods like Fairmount, where poor minority families were able to be evicted without question. Federal protection of home equity loans heightened the appeal of historic-preservation tax credits that had been available since 1976, creating cash incentives for developing land on historic sites [9]. In addition to developer gentrification, Reagan’s war on drugs had drastic effects on Pennsylvania’s incarcerated population [10].

Pennsylvania in particular was incarcerating African Americans at disproportionate rates, which made more real estate available in areas with high percentages of Black residents. This, coupled with tax incentives and the desire to gentrify, allowed real estate developers to raise rents and displace African Americans to concentrated neighborhoods in the city, which can be seen in the racial compositions of gentrified Philadelphia neighborhoods today [11]. Through the 1980s, the abandoned Eastern State began to stand out as the only old colonial style building in a neighborhood getting transformed by urban renewal—standing out as much as it did when it was first constructed nearly 150 years before.

In 1971, the city acquired title to the prison from the Commonwealth for $400,000. The next two decades saw several efforts to demolish and repurpose Eastern State. In 1974, former Philadelphia chief of police and then mayor Frank Rizzo suggested that Eastern State be demolished to create a criminal justice center for the city [12]. This plan was quickly abandoned, but as the 1980s continued and the Fairmount area saw expanding economic growth, the city transferred Eastern State to the Redevelopment Authority to find commercial use for the 11-acre plot. Several redevelopment plans were brought to the city to figure out how to commercialize the land Eastern State sat on. Proposals for a theme park, luxury apartments, and a shopping center crossed Mayor Wilson Goode’s desk. All were denied. According to a 1988 Philadelphia Inquirer article:

Mayor Goode derailed a $20 million plan to turn Fairmount’s abandoned Eastern State Penitentiary into a shopping center yesterday, saying that development plans would destroy its historic value. At Goode’s request, the Redevelopment Authority voted not to award the project to any of the three developers who had proposed changing the old cell blocks into shops. Goode apparently caved in to pressure from historical preservationists, who had complained that all three proposals called for tearing down some prison buildings [13].

These individuals, who were able to convince the mayor to save the prison from land developers, came to be known as the Eastern State Task Force. The Task Force was composed of an eclectic group of individuals like Temple professor and historian Ken Finkel, the Mütter Museum’s Gretchen Worden, and the National Park Service’s Bill Bolger. The demographics and interests of the Task Force, however, did not reflect the neighborhood. As Bruggeman describes, “Rather, these young, highly educated, and predominantly white culture activists—none of whom were Fairmount natives and few, if any, with ties to real prisoners—took it upon themselves to challenge decades of Pollyannaish preservation in Philadelphia” [14]. The Task Force had to move quickly, as they were only given one day’s notice that Mayor Wilson Goode would be hearing arguments against redevelopment in April of 1988. The Task Force was successful in getting the mayor on their side, who rejected all plans proposed by the Redevelopment Authority due to lack of “demonstrated feasibility.” Eastern State was officially saved from bulldozers [15].

Next came the daunting task of preserving the prison and figuring out what new purpose it should serve. The Task Force became the de facto curators of the prison, but it sat largely untouched for almost two decades, in dilapidated state. Bruggeman discovered that plans arose for Eastern State to potentially shelter drug addicts, serve as a storage center for museums all around the country, or even headquartering the American Correctional Association [16].

In 1991, the Task Force came up with the idea to give tours of the prison around Halloween to raise extra funding. The event was a huge hit, with both the museum and surrounding businesses profiting handsomely. It became an annual tradition. With a final round of funding from the Pew Charitable Trust that same year, major stabilization and preservation efforts undertaken, and the idea of turning the prison into a museum mobilized [17].

Through rounds of fundraising in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Task Force’s goal to preserve Eastern State in its historic glory drew neighborhood-level criticism for lack of inclusion. Although the Task Force deserves credit for keeping Eastern State alive in the first place, their position as wealthy white intellectuals focused solely on historical preservation inhibited outreach. Repeatedly over twenty years, concerns emerged about whether the Task Force listened to stakeholders from the neighborhood. The Task Force sometimes “forgot” to add community members to committees, and delayed projects that required community input as much as possible.

Plans to stir community interest in the 1990s involved beautifying the side of the prison that faced Fairmount Avenue, the section of the perimeter with wealthier residents and more businesses. The proposal did little for poorer neighborhoods that straddled Brown Street and Corinthian Avenue. Although this proposal was later rejected due to the concern that it would create animosity with surrounding neighborhoods, it spoke volumes about the socio-economic gaps created by gentrification. In 1994, neighbors complained about rampant drug use and prostitution in the Brown and Corinthian areas, but the Task Force did not act on the issue until enraged neighbors directly petitioned City Hall to intervene over a year later.

The museum as we know it today finally opened for daily historic tours in 1994, when nearly 10,000 visitors with hard hats (and signed waivers) took tours. Granted, the museum now makes efforts to teach its visitors about unequal rates of incarceration. With the “Big Graph,” visitors can see how massive mass incarceration is. The “Prisons Today” exhibit shows visitors everyday things that could send them to jail if they came from a targeted racial demographic. There is also an exhibit to Jewish life at Eastern State, and even an audio tour remembering the lives of the prisoners, The Voices of Eastern State,” narrated by actor Steve Buscemi [18].

However, at the time of the museum’s founding, none of these ideals or proposals were remotely present in the ambitions of the Task Force, nor the later Historical Commission. Bruggeman sums up this almost purposeful neglect perfectly:

Since the early 1990s, the task force and its descendant—Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site Inc.—have, in fact, mentioned [including more about the neighborhood and former prisoners] frequently with neighbors, former inmates, and past employees during periodic on-site inmate reunions and in conjunction with an ongoing oral history initiative. These projects have provided fascinating insights into Eastern State’s place in Fairmount during the twentieth century and shed light on precisely those questions about race, class, and incarceration that concern the new prison history. It is unclear, though, if they will be enough to persuade neighbors to engage in ‘lively civic debate around current correctional policy.’ Doing that will require more. It will require that Eastern State somehow contend with the legacy of the task force’s formative decision to preserve the penitentiary without first confronting the depth of its living memory [19].

Through a historical analysis of the 23-year period during which Eastern State Penitentiary transformed from an active prison to a deserted wasteland to a museum, a few things stand out. Although this can be considered one of the most significant victories for the historical preservation movement, Eastern State’s rebirth has glaring undertones of white privilege, neighborhood neglect, and racial division. Eastern State’s transformation perfectly situated itself within Philadelphia’s urban renewal narrative: displacing minority-filled neighborhoods to make way for the commercial interests of white professionals, who historically did not call Fairmount home.

[1] Jennifer Lawrence Janofsky, “Eastern State Penitentiary,” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/category/jennifer-lawrence-janofsky/.

[2] Janofksy, “Eastern State Penitentiary.”

[3] Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Pantheon Books, 1977).

[4] “The World’s First True Penitentiary: Eastern State.” DiscoverPHL.com, 13 July 2021, https://www.discoverphl.com/blog/the worlds-first-true-penitentiary-eastern-state/.

[5] Francis X. Dolan, Eastern State Penitentiary (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2007), https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C4453002,114.

[6] “About Eastern State,” Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, https://www.easternstate.org/about-eastern-state.

[7] Timothy J. Lombardo, “The Battle of Whitman Park: Race, Class, and Public Housing in Philadelphia, 1956–1982,” Journal of Social History 47, no. 2 (2013): 401–28, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305920.

[8] Seth C. Bruggeman, “Reforming the Carceral Past: Eastern State Penitentiary and the Challenge of the Twenty-first-Century Prison Museum.” Radical History Review 113 (2012): 171–186, https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-1504975, 171.

[9] Bruggeman, “Reforming the Carceral Past,” 176.

[10] Incarceration Trends in Pennsylvania,” Vera Institute of Justice, Dec. 2019, https://www.vera.org/downloads/pdfdownloads/state-incarceration-trends-pennsylvania.pdf.

[11] Pew Charitable Trusts, “Gentrification and Neighborhood Change in Philadelphia,” 19 May 2016, https://www.pewtrusts.org/research-and-analysis/articles/2016/05/gentrification-and-neighborhood-change-in- philadelphia.

[12] “Timeline,” Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, https://www.easternstate.org/research/history-eastern- state/timeline.

[13] Catherine Lucey, “On This Day In 1988,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 30 Apr. 1988, https://www.inquirer.com/philly/blogs/clout/On_This_Day_In1988.html.

[14] Bruggeman, “Reforming,” 177.

[15] Lucey, “On This Day in 1988.”

[16] Bruggeman, “Reforming,” 178.

[17] “Timeline,” Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, https://www.easternstate.org/research/history-eastern- state/timeline.

[18] “Exhibits,” Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, https://www.easternstate.org/explore/exhibits.

[19] Bruggeman, “Reforming,” 181.

[20] Janofsky, “Eastern State Penitentiary.”

[21] Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, https://www.easternstate.org.

Works Cited

Janofsky, Jennifer Lawrence. “Eastern State Penitentiary.” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/category/jennifer-lawrence- janofsky/.

“About Eastern State.” Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, https://www.easternstate.org/about-eastern-state.

Bruggeman, Seth C. “Reforming the Carceral Past: Eastern State Penitentiary and the Challenge of the Twenty-First-Century Prison Museum.” Radical History Review, vol. 2012, no. 113, 2012, pp. 171–186., https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-1504975.

Dolan, Francis X. Eastern State Penitentiary. Arcadia Pub., 2007.

“Exhibits.” Exhibits | Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, https://www.easternstate.org/explore/exhibits.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Pantheon Books, 1977.

“History of Eastern State.” Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, https://www.easternstate.org/research/history-eastern-state.

“Incarceration Trends in Pennsylvania.” Vera Institute of Justice, Dec. 2019, https://www.vera.org/downloads/pdfdownloads/state-incarceration-trends- pennsylvania.pdf

Lucey, Catherine. “On This Day in 1988.” Https://Www.inquirer.com, The Philadelphia Inquirer, 30 Apr. 1988, https://www.inquirer.com/philly/blogs/clout/On_This_Day_In1988.html.

“The World’s First True Penitentiary: Eastern State.” DiscoverPHL.com, 13 July 2021, https://www.discoverphl.com/blog/the-worlds-first-true-penitentiary-eastern-state/.

“Timeline.” Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site, https://www.easternstate.org/research/history-eastern-state/timeline.