Artist: Ōnishi Chinnen 大西椿年

Date: 1819

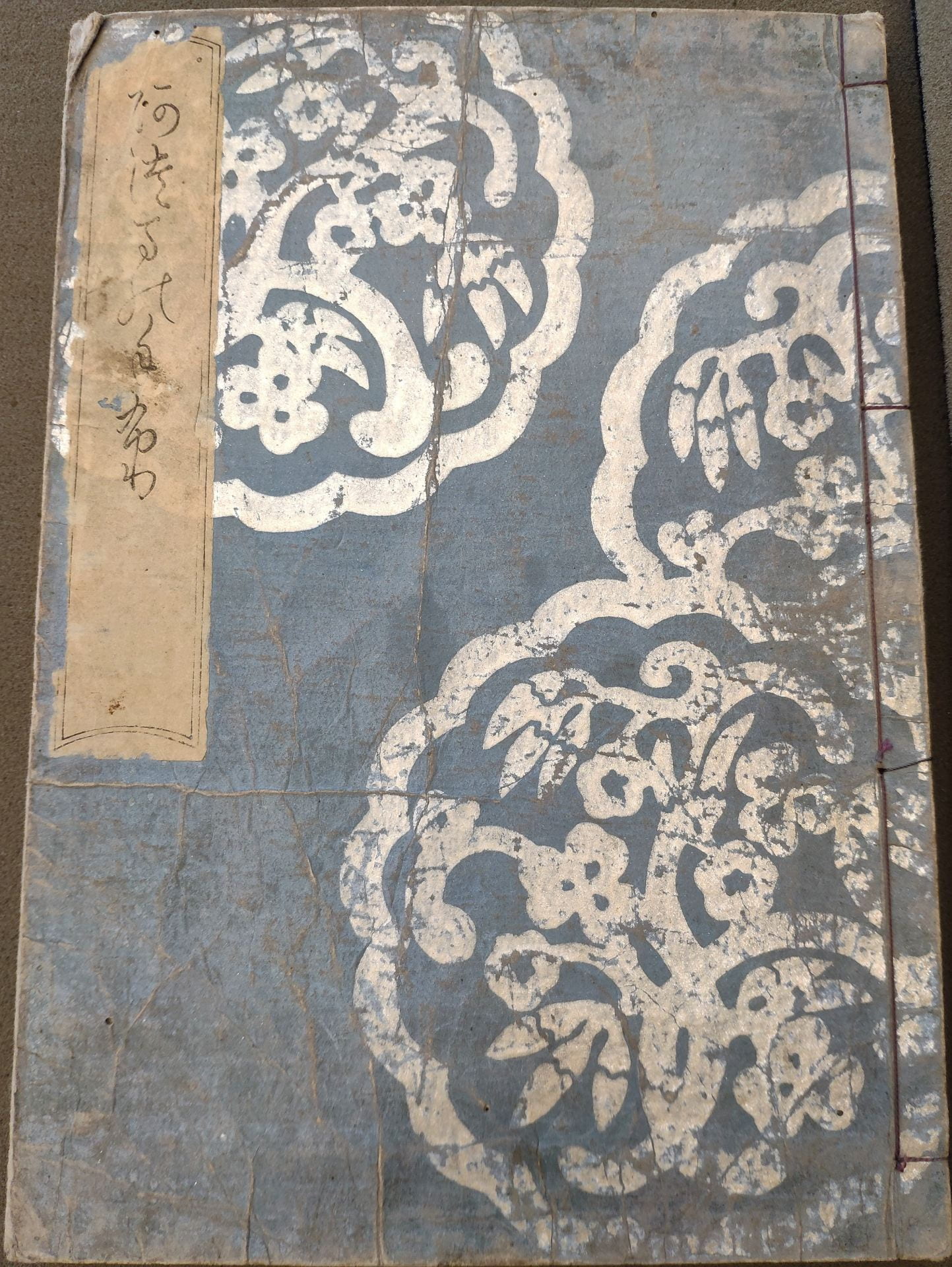

Medium: fukurotoji (pouch binding), woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

Publisher: Osakaya Genbei, Kobayashi Shinbei

Gift of Arthur Tress, Tress Box 22, Item 13, https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977502751403681

Other Known Copies: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Pulverer Collection in the Freer Gallery of Art, National Institute of Japanese Literature, The British Museum

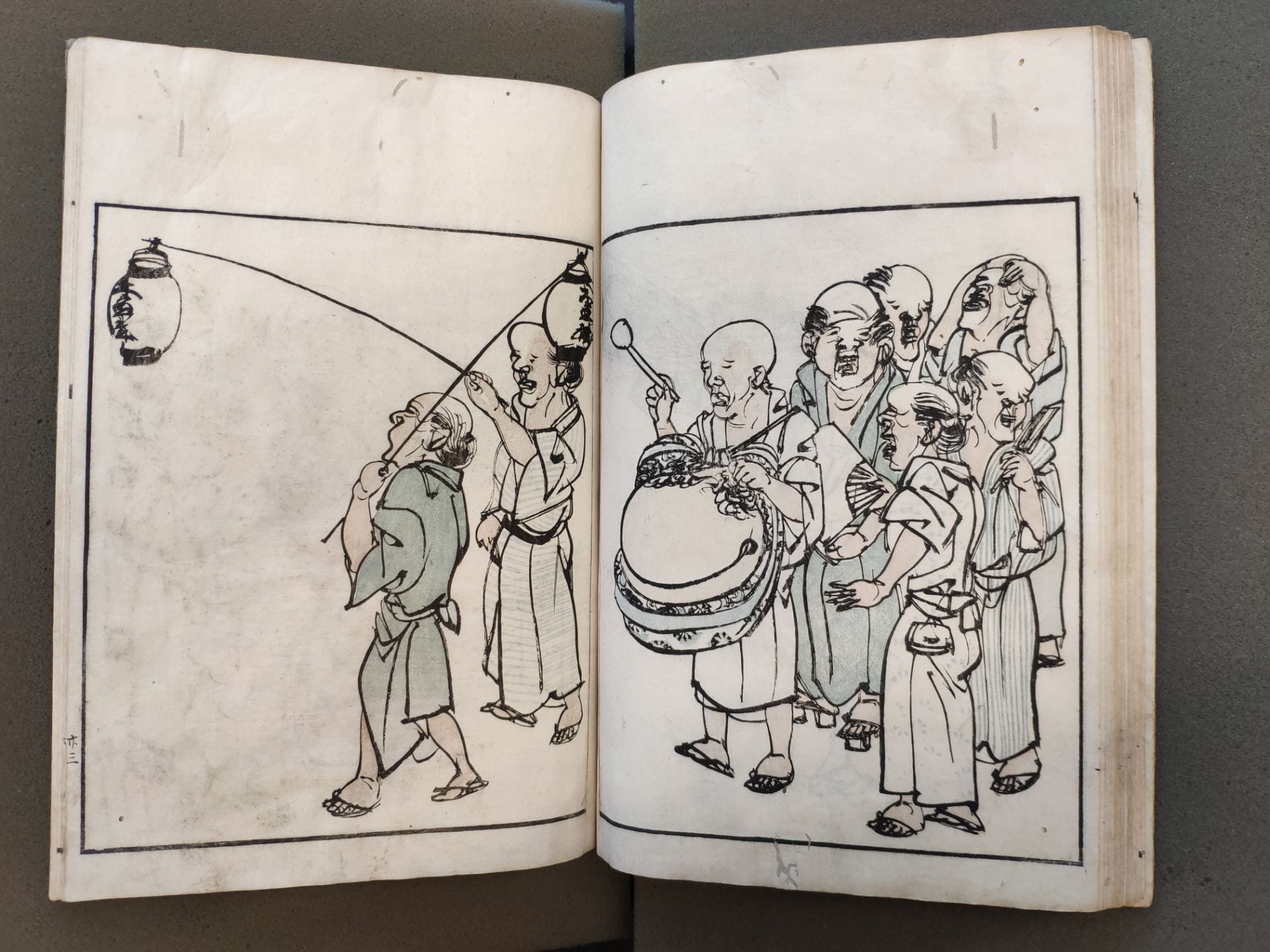

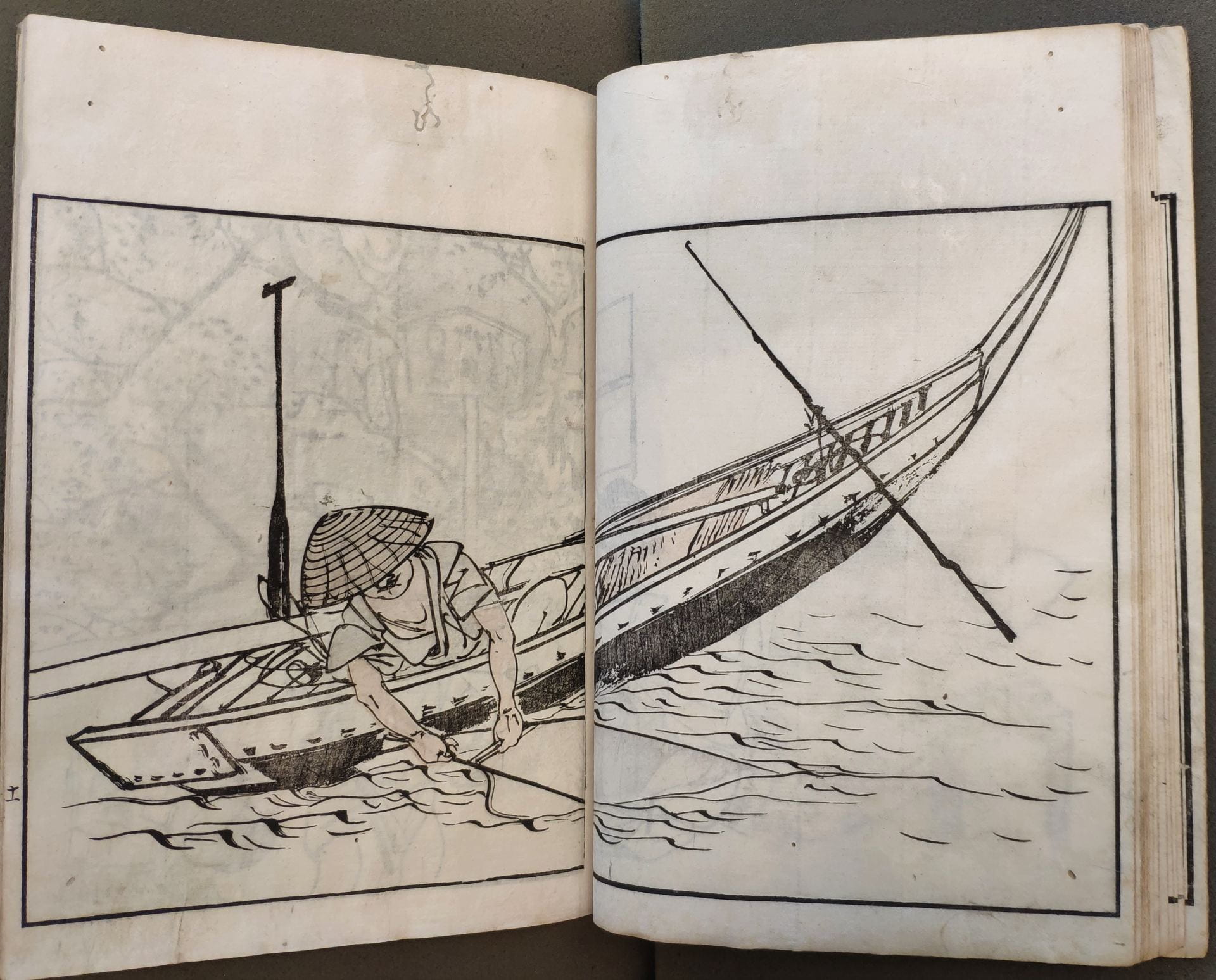

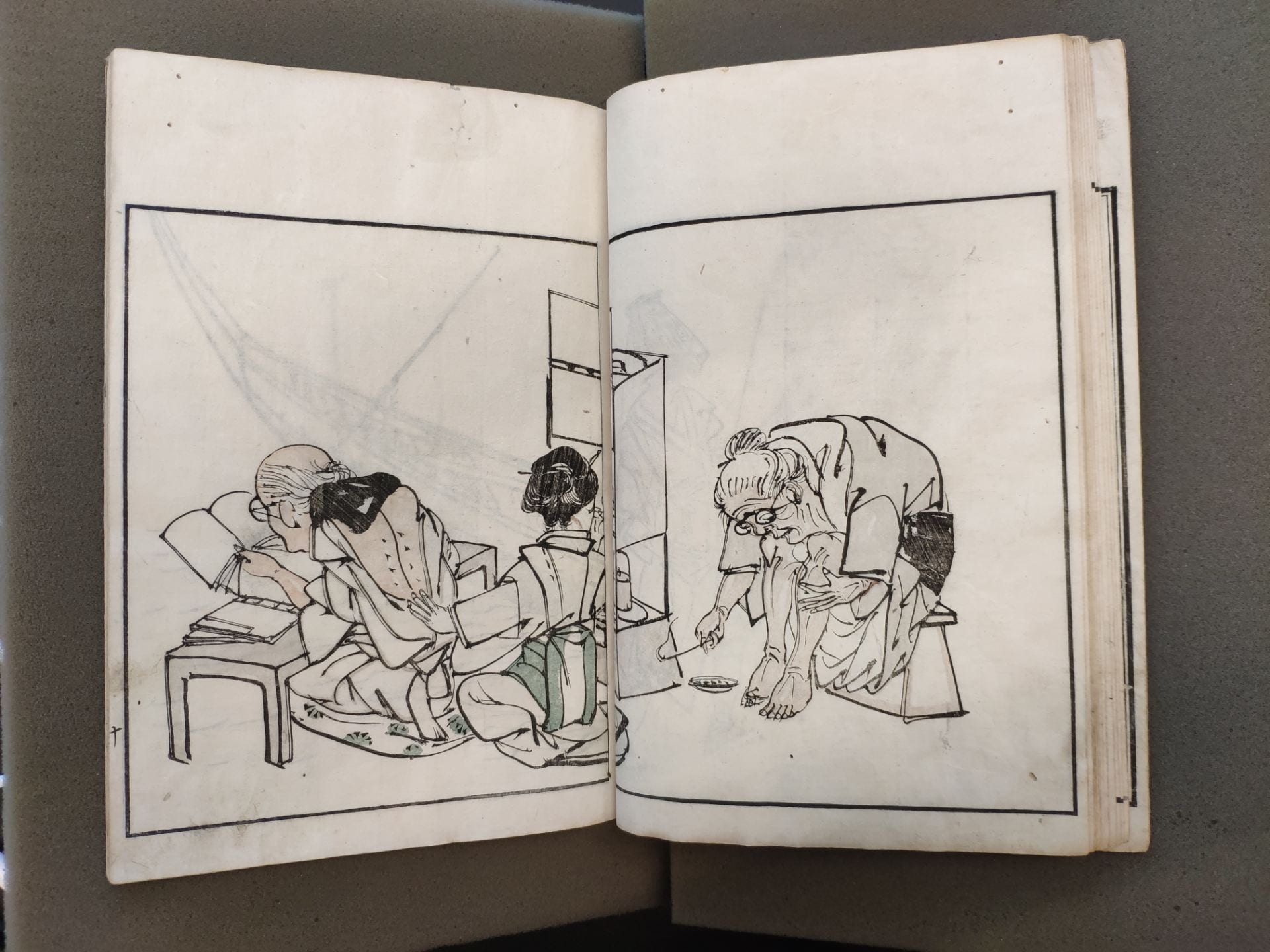

This e-hon, or picture book, by Ōnishi Chinnen (1791-1851) is bound in pale blue paper covers and decorated with large mica roundels stenciled in silver. Titled Azuma no teburi, this is Chinnen’s best known work, and it chronicles the daily frenzy of urban life in the capital: manual laborers ply their trade, women engage in domestic chores, and a toy-seller hawks his wares near playing children. The scenes are rendered with a graphic, highly gestural line that was distinctive of artists trained under masters of the Shijō school. Chinnen was pupil to both Tani Bunchō and Watanabe Nangaku, who repopularized naturalism in their use of birds and flowers as subjects. Chinnen’s lively strokes add a sense of movement and immediacy to his subjects, as if the scenes were drawn from close proximity. The viewer of Chinnen’s work thus becomes like a voyeur, and enjoys the pleasure of gazing unhurriedly at a scene that would quickly pass in the street. This quality illustrates what Jack Hillier calls the peculiar “limpidity” of Chinnen’s drawings. (Hillier 769)

Chinnen was born to a high-status family and worked as an official checker of government rice warehouses at Kuramae. The scenes of Azuma no teburi are topical to Chinnen’s civic occupation and daily work-route through the city. Each scene spans two pages and is framed by a thin black border. In one scene, the border frame is broken when two children play hanetsuki, a badminton-like sport, and their birdie bounces beyond the border. Here, Chinnen visually communicates the interplay between the boundaries of the game and the boundaries of the artist’s print block. By doing so, he engages the reader in a bit of wordplay in a text that has virtually no words. As such, Azuma no teburi broaches the question of its audience. What sort of 19th c. reading public is assumed by the sociological, civic, whimsical themes of Chinnen’s picture book?

Selected Reading:

Brown, Louise Norton, Block Printing & Book Illustration in Japan. London: Routledge, 1924, pp. 106.

Hillier, Jack. The Art of the Japanese Book. New York: Sotheby’s Publications, 1987, pp. 768-70.

Note: Book cover may have Sorimachi Shigeo’s handwriting

Posted by Ann Ho, Fall semester, 2019