Artist: Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾北斎 (1760-1849)

Title: Ryakuga hayaoshie 略画早指南

Date of Publication: 1812 for volume 1, 1814 for volume 2. Publisher: Unspecified.

Medium: Woodblock printed, ink on paper

Dimensions: Chūbon: 18.6 x 13.1 x 0.7 cm

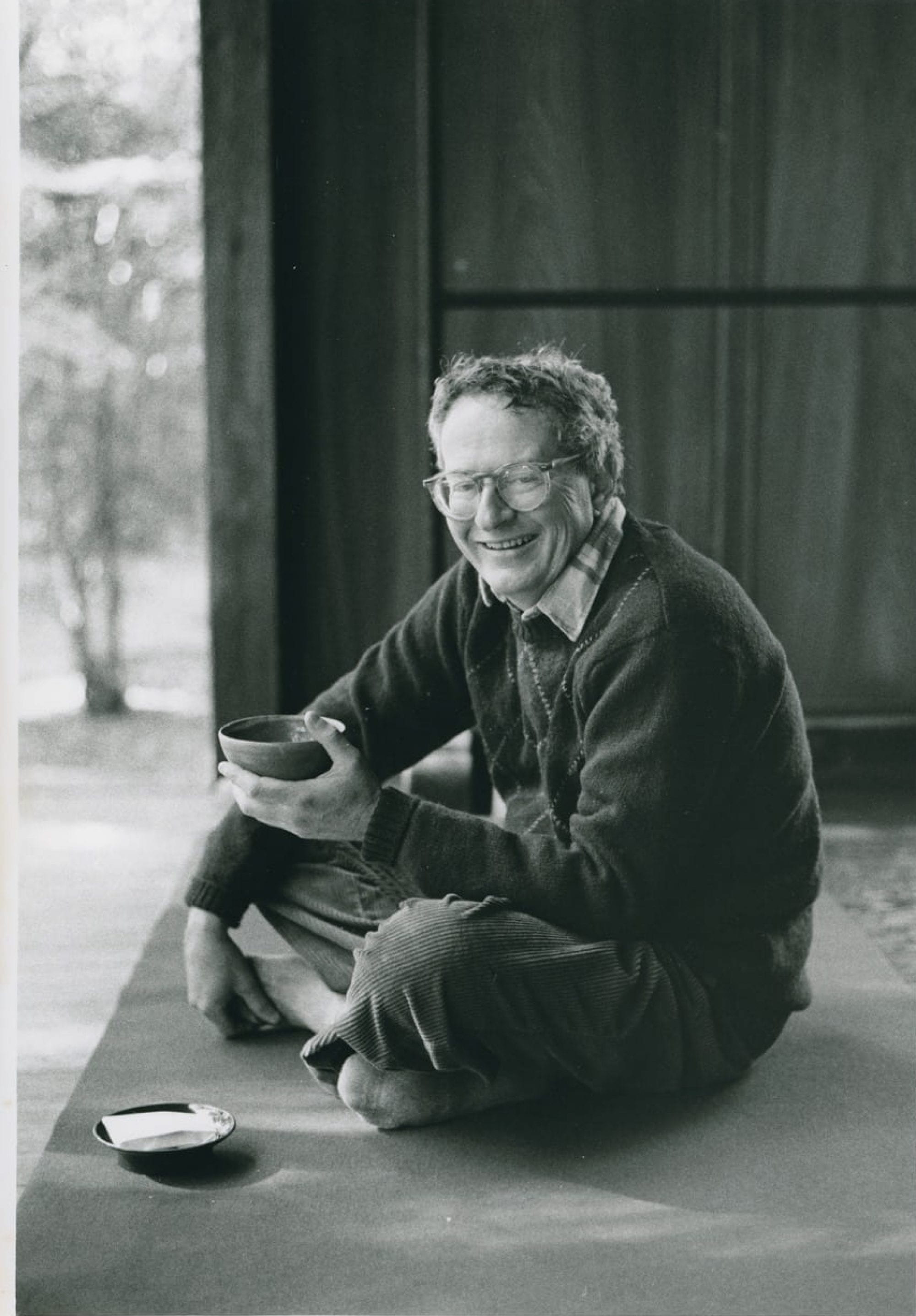

Gift of Arthur Tress

Kislak Center for Special Collections – Arthur Tress Collection. Box 16, Item 10.

See digital images here

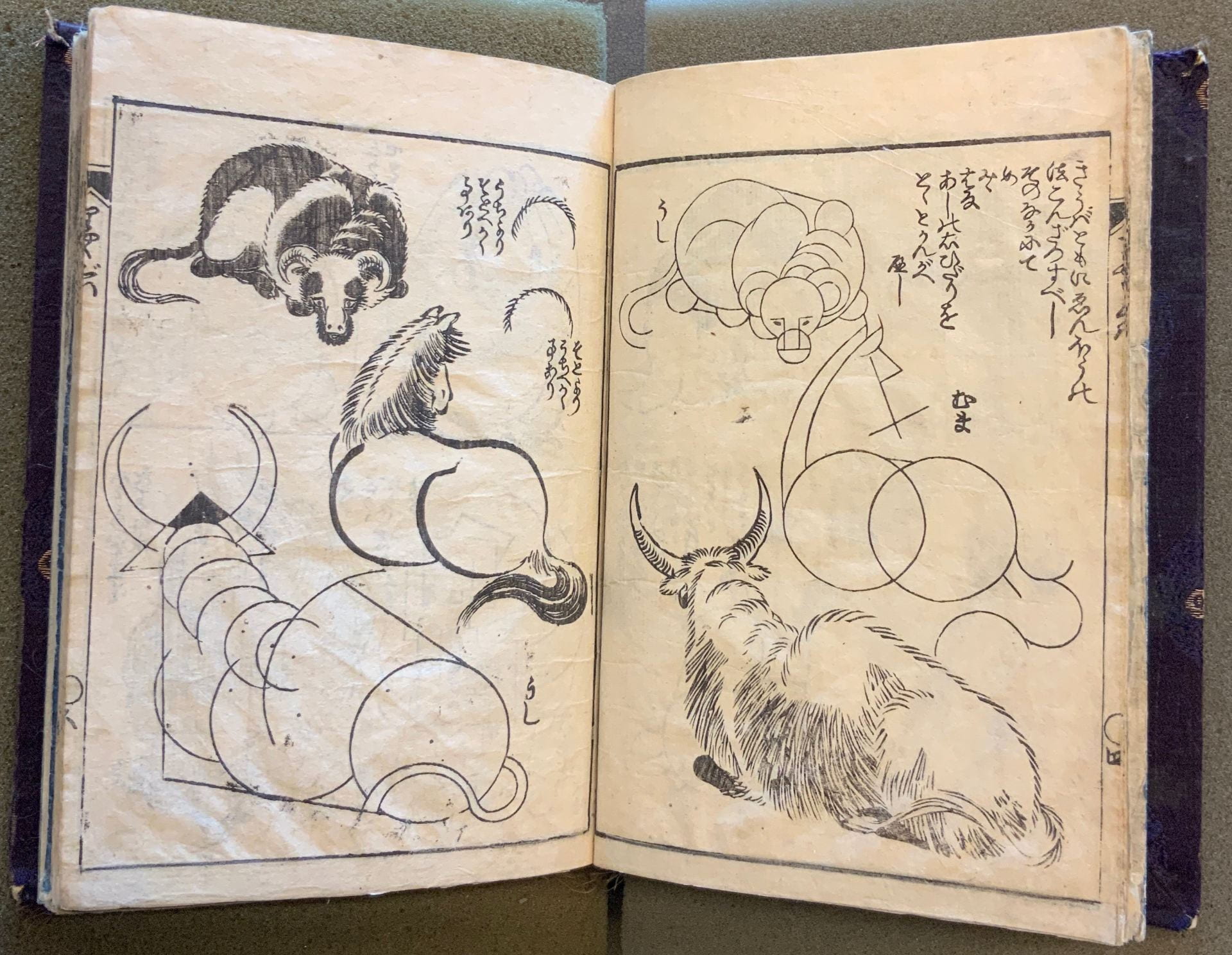

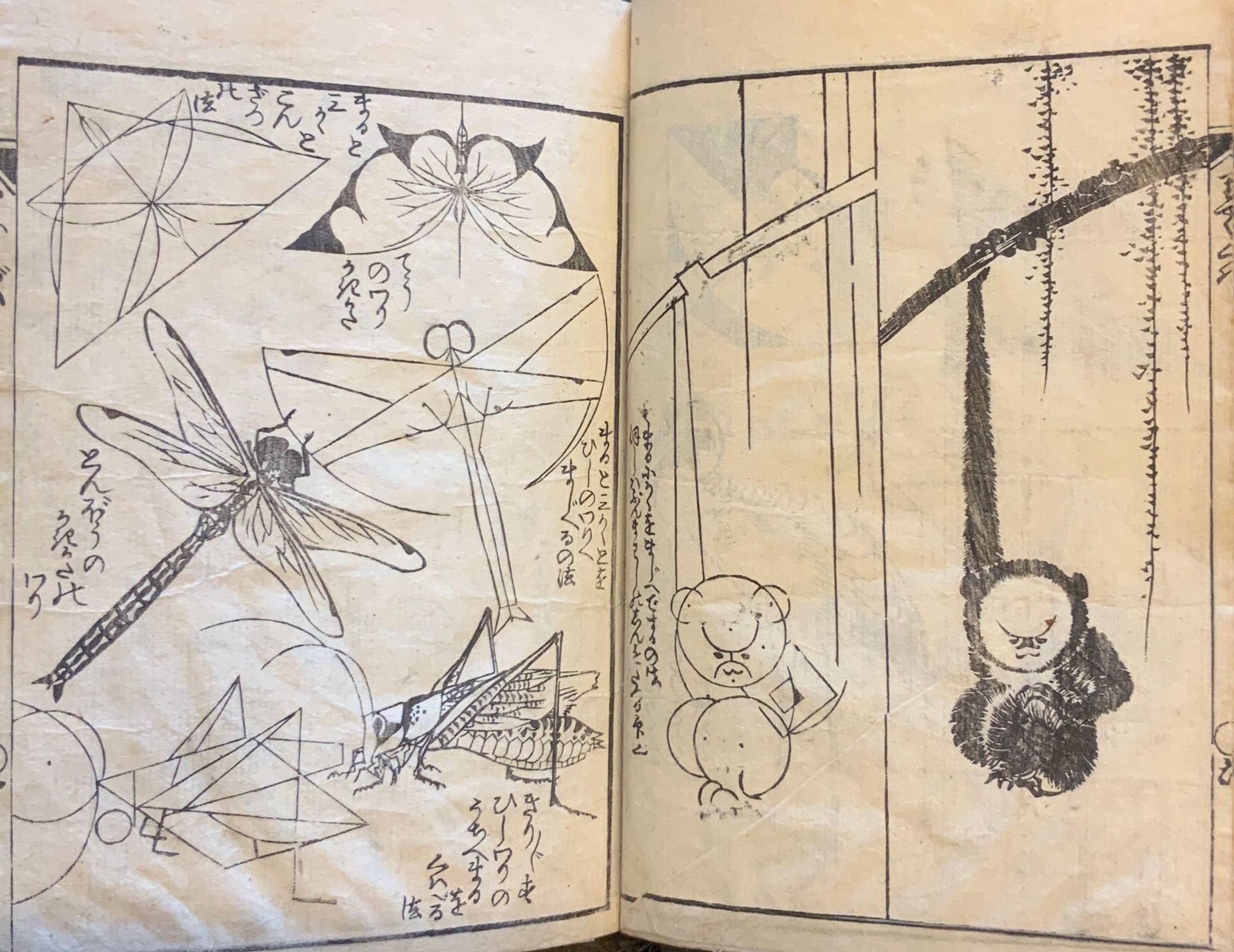

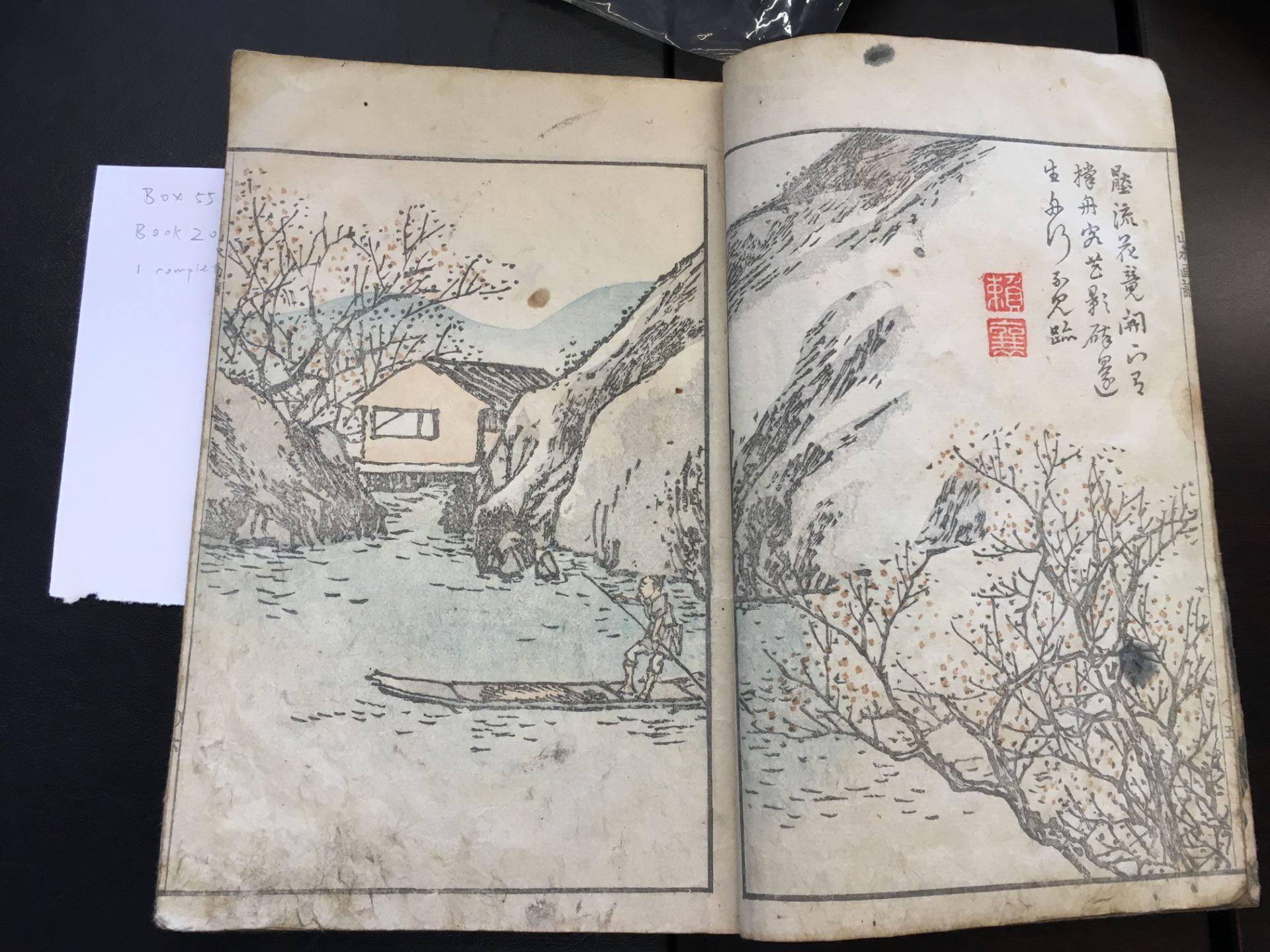

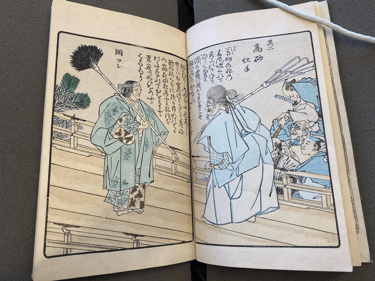

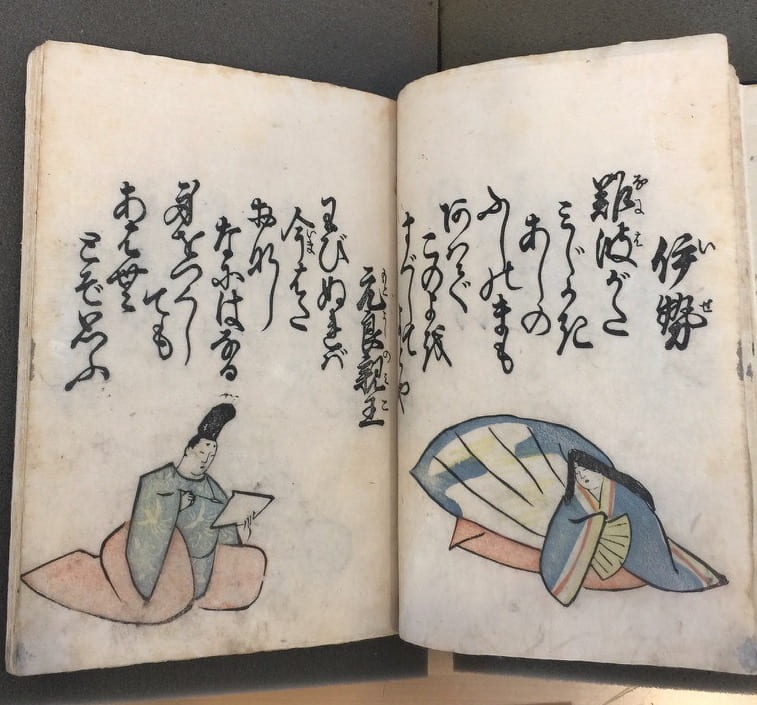

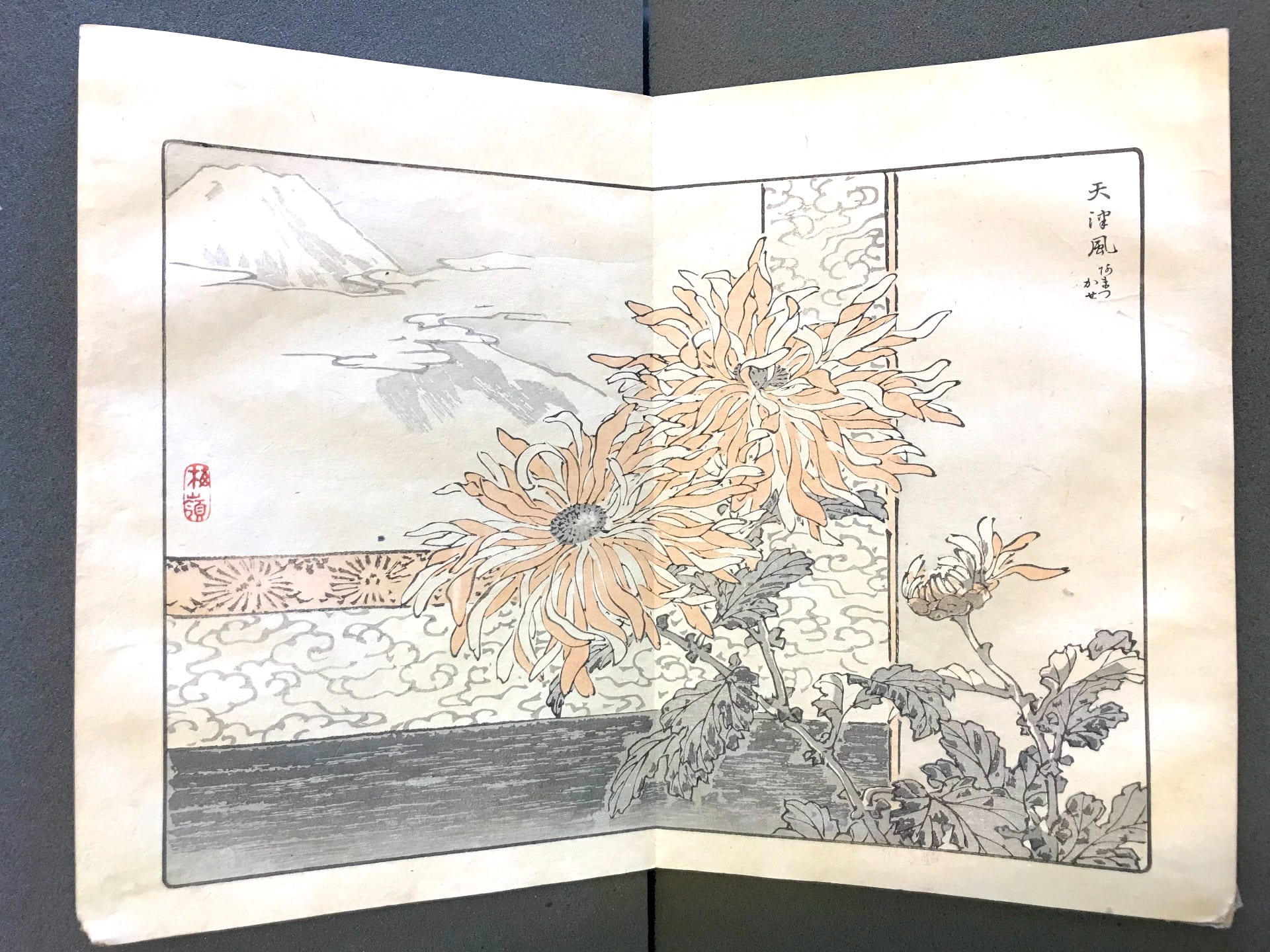

Hokusai designed this book, Ryakuga hayaoshie, as a drawing instruction manual. It was printed in three volumes and in each Hokusai demonstrates principles of design. The Tress Collection includes two volumes from the set. In volume 1, Hokusai breaks the drawings down into simple geometric shapes. Volume 2 focuses on the contours of the drawing and characters. By looking at other collections, we can see that in volume 3, Hokusai diagrams the line strokes and order of making them (see for example, the copy held in the Pulverer collection). The Tress copy was part of an important French collection assembled in the 1880s by E. Gillet. In addition to rebinding the books, Gillet may have also written the extensive notes in French that appear in the back of the second volume, as well as added floral interior and exterior patterns to the books front and back covers.

In Ryakuga hayaoshie, or Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing, Hokusai intended to teach drawing methods to a varied audience. This genre of book was inspired by Chinese models that presented techniques for creating paintings by building on simple to complex forms using simple brushstrokes.

The theme of Hokusai’s first volume is to use shapes and forms to show how to break down complex renderings. As we can see in the illustration from volume one, Hokusai explores a few foundational drawing concepts through beautiful renderings of three animals, in various stages of finished images. Corresponding to the fully rendered drawing of each animal, on the opposite page there is instruction on how to construct the finished rendered form. For example, in the bottom right corner Hokusai shows a finished rendering of an animal, which appears to be some form of bull or yak, and then on the opposite page breaks down the animal’s construction into its simple geometric shapes. These shapes consist of circles, a triangle, and linear lines. These lines act as a basic contour, gesture, and the form of the figure and the geometry that the shape and line represent. It has been reported that Hokusai believed that anything could be rendered from simple shapes. In the top left corner, Hokusai shows how to render animal hair. By following the shape of a circle Hokusai skillfully uses a brush to draw hairlines on the contour of the circular shape. Looking back to the drawing in the bottom right corner (the bull/yak), the shapes are no longer visible and there is more gesture in the illustration, yet the original geometric forms are still evident given the hair in the middle of the drawing creates a circular shape. In addition to this, the top back of the animal shows a circular line, clearly visible through the gesture of hair. We can see the line even though it is not drawn in.

In the second volume, Hokusai uses the theme of Japanese characters as a structure for his drawing, as a method to build gesture and contour line drawing. For example, in the illustration shown here, Hokusai shows renderings of landscapes. Like Volume One, where Hokusai breaks down a drawing from fully rendered form to simple geometric shapes, here he uses a similar method of simplification in explaining how to draw the forms. For example, the landscape shows a hillside, trees, and small man-made structures. Above this landscape, the contour lines in the calligraphy act as the structure of the drawing. Upon further inspection when looking at the fully rendered form any reader can clearly see the calligraphy taking shape of the hills, the tree, and the small structures. Hokusai gave the reader many tools to approach a drawing. Finally, on later pages in the book, Hokusai also teaches the reader how to hold and make lines with a brush. The brush is an extension of the artist and must also be taken into consideration as an area of study.

Also see the commentary for the book here: http://pulverer.si.edu/node/314/title/1

Posted by Derek Rodenbeck

April 15th, 2020