Artist: Kawamura Bunpō (河村文鳳, 1779-1821)

Title: Kanga shinan nihen 漢画指南二編 (Instruction in Chinese Painting, Part Two)

Publishers: Yamatoya Kanbē 大和屋勘兵衛, Fushimiya Tōemon 伏見屋藤右衛門, Hishiya Magobē 菱屋孫兵衛

Block Carver: Inoue Jihē 井上治兵衛

Date: 1811

Medium: Woodblock printed, ink and color on paper

Gift of Arthur Tress, Arthur Tress Collection, Bunpō 3 (formerly Box 2, Book 3)

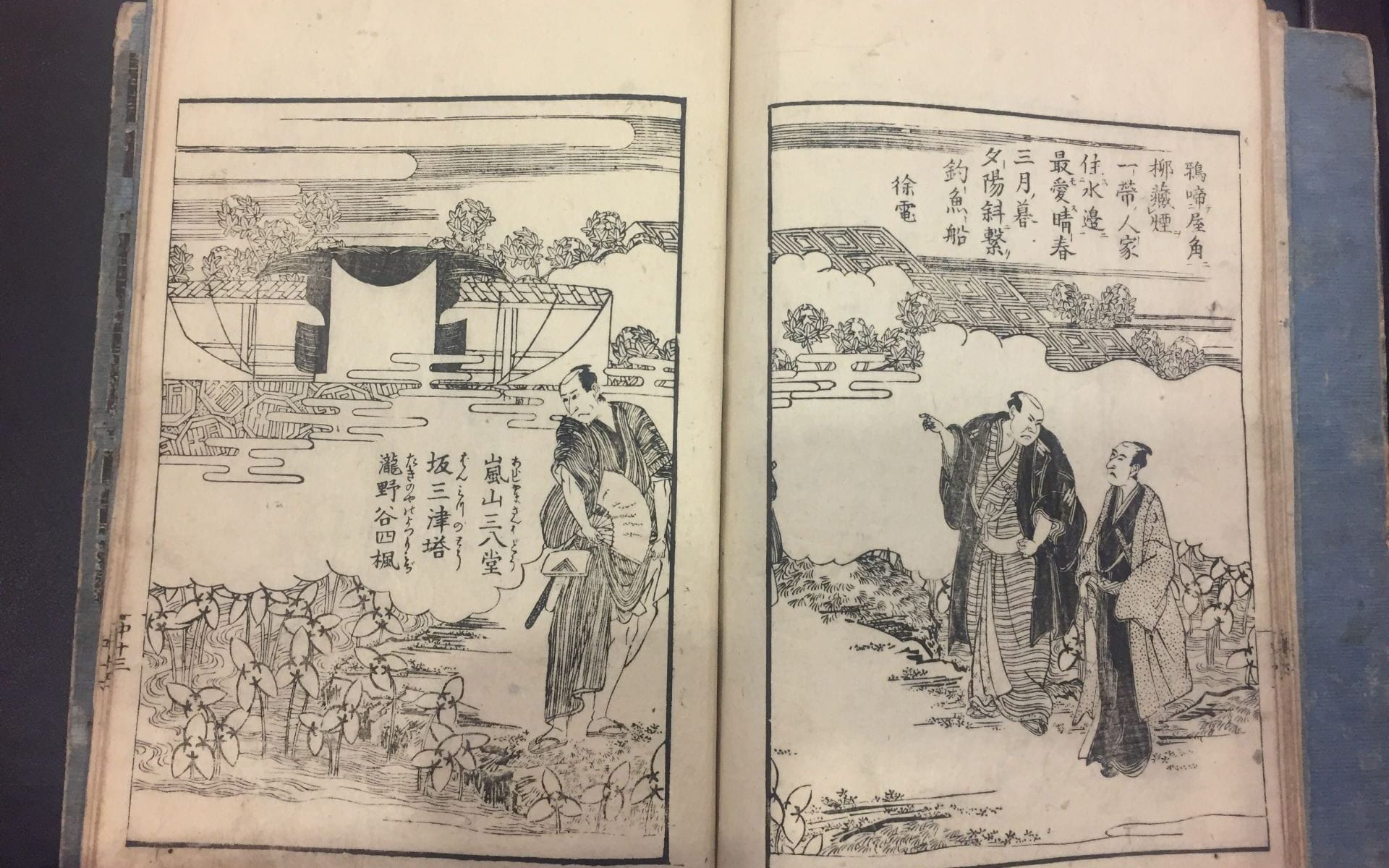

Like other painters of his generation, Kawamura Bunpō was not able travel to China due to period prohibitions but learned about Chinese painting and culture via printed books, paintings, poetry, literature, and other media.

Entitled Kanga shinan nihen (漢画指南) or Instruction in Chinese Painting, Part Two, this book was designed as the sequel to the Kanga shinan, a book featuring designs by Takebe Ayatari (建部綾足, also known as Kan’yōsai 寒葉斎1719–1774), published in 1778. As historian Ellis Tinios notes, Ayatari’s Kanga shinan “. . . was so highly regarded that the Kyoto publisher Hishiya Magobē (Gosharō 五車楼) reprinted it in 1811 using the original blocks. At the same time, he commissioned Kawamura Bunpō to produce a second part (nihen)” (Tinios). The colophon includes the name of block carver, Inoue Jihē, attesting to the publisher’s commission, too, of this highly appreciated artisan in the production of this exceptional book.

The three-volume title presents a variety of Chinese-style elements for aspiring painters, from studies of trees, grasses, and dwellings, to figures and landscape vignettes, all labeled in Chinese. The publisher called it ““a tool for the study of Chinese painting,” adding that “if you take this book as your manual for the study of Chinese painting, without a teacher, on your own, you will be able to master a marvelous style of Chinese painting” (translated by Tinios).

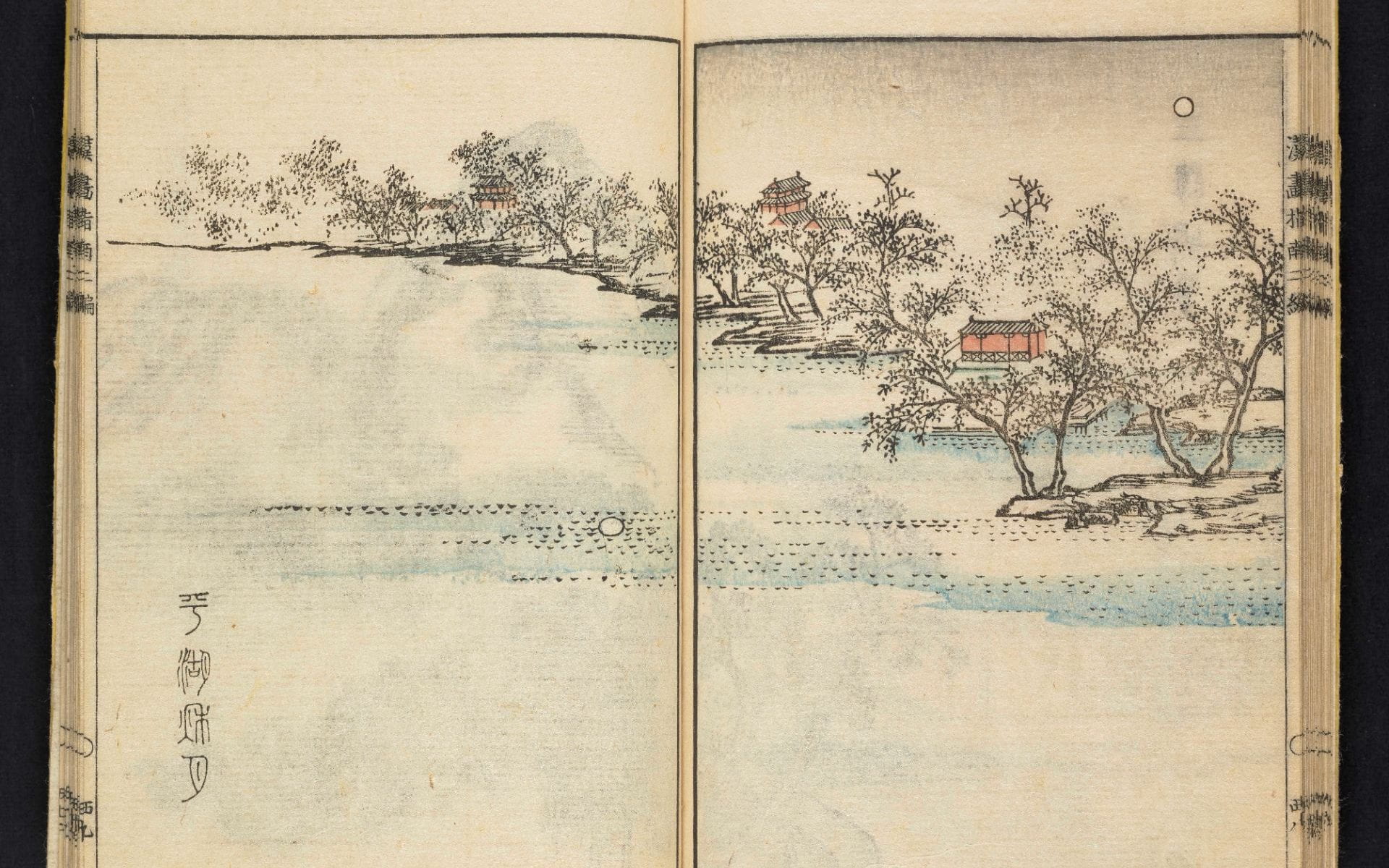

In the third volume, Bunpō ends the sequence of selected studies and indicates a new sequence with an opening showing a view through a window of a plum tree in moonlight on the right and a stele with an inscription reading “Views of West Lake” (西湖の図) on the left.

In the final twenty-one openings, Bunpō adapts views of the renowned West Lake in China, in scenes such as the one shown at the top of this post.

Long appreciated for its great beauty, the site of West Lake was a painting and poetry theme in China since the Song dynasty. The subject became well known in Japan, employed by Japanese painters since the Muromachi period. What is rather remarkable about Bunpō’s sequence is how closely the compositions match those included in a Chinese book, Nanxun shengdian 南巡盛典, the Great Canon of the Southern Tours compiled by Gao Jin and others, published in 1771. This Chinese book documenting Emperor Qianlong’s tours in the south was imported to Japan in 1774 (Ōba 1967). How Bunpō came to know this Chinese title remains an open question, but the connection demonstrates how much Japanese painters relied upon Chinese printed books for source material.

Other copies:

British Museum

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Pulverer Collection of Japanese Illustrated Books, Freer and Sackler Galleries

Portland Art Museum

Selected Reading:

Masaki Itakura, Egakareta miyako: Kaihō, Kōshū, Kyōto, Edo (Tokyo: Tokyo Daigaku Shuppankai, 2013).

Ōba Osamu, Edo jidai ni okeru tōsen mochiwatarisho no kenkyū (Kansai Daigaku shuppanbu, 1967).

Ellis Tinios, “Commentary,” Kanga shinan nihen, The World of the Japanese Illustrated Book, (https://pulverer.si.edu/node/372/title/1)

Ellis Tinios, Kawamura Bumpō: Artist of Two Worlds. Leeds, U.K.: Leeds University Gallery, 2004.

Written by Tim Zhang, edited and posted by Julie Nelson Davis, March 17, 2022