Thus far on our trip we had seen Claude Monet’s carefully designed home and studio with its vibrant colors, overflowing amounts of light, and collection of Japanese prints. We also visited the Musée d’Ennery, a small museum of Asian art, tucked away in the 16th arrondissement, that what was once the private residence of collector Clémence d’Ennery. At the Musée Guimet we had the opportunity to see the sprawlingly ambitious exhibition Meiji, Splendeurs du Japon impérial (1868-1912). In one section of the exhibition there is a gallery focused on Japonisme, the intense fascination with all things Japanese. Removing all the labels from the objects, the museum encourage visitors to guess who made the objects on display and where they came from. We can think of an additional question here: how did people engage with these “Japanese” objects? This fall at Penn, noted interior designer Ilse Crawford gave a lecture as part of the 2018-2019 Wolf Humanities Center’s forum on stuff where she discussed the ways in which we live with the objects that surround us and how we make sense of space.The Musée des Arts Décoratifs is a collection of the things we live with.

Founded in 1864 by a group of wealthy French businessmen, the museum’s permanent collection developed mostly from these private collections. Consisting of some 150,000 objects from the middle ages to the present, the museum’s collection includes furniture, ceramics, glassware, costumes and textiles, graphic design, jewelry, metalwork, woodwork, and toys.

The collection is displayed through two primary modes: a chronological overview of technological developments in techniques and ten rooms arranged in thematic groupings and according to chronological period. Period rooms are often assembled under the notion that changes in period/style reflect the zeitgeist of the time. These kinds of spaces offer visitors an immersive experience similar to World Fairs. Period rooms also bring to the fore issues of class and gender as they are often displays of individual property and the private residences of the wealthy. But there is also the other end of the economic spectrum on display at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. Prominent examples of period rooms can be found at the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and our own Philadelphia Museum of Art. But there are some potential problems with these spaces. They can run the risk of oversimplification, verging into the territory of theater sets for entertainment. They also raise the perennial question of authenticity and leave us to wonder how we display these things. How much creative licensee do we take and to what end? And then there is the issue of periodization that assumes a neat, easily recognizable moment that fits into a chronology.

All of these threads come together in the object I selected for my object presentation, Félix Bracquemond’s Rousseau dinner service designed in 1866 and produced by Creil-Montereau Factory. Displayed in Japonisme Salon, the Rousseau set is considered one of the earliest examples of Japonisme in French ceramics combining eighteenth-century shapes with Japanese designs directly from a manga by Katsushika Hokusai.

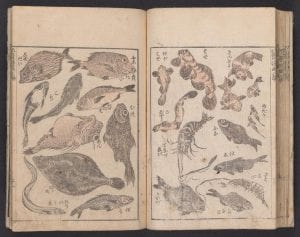

Katsushika Hokusai, Denshin kaishu (Hokusai’s Manga), published 1814-1878, vol. 2 pg. 47-48. Smithsonian Libraries.

Bracquemond was an important figure in promoting printmaking in general and Japanese prints in particular among Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists. In 1856 while in a Paris printer’s shop, Bracquemond came across Hokusai’s manga sketches. The manga comprises thousands of images ranging from flora and fauna, to scenes of everyday life, landscapes, and the supernatural across fifteen volumes. (All fifteen volumes are digitized and available on the Smithsonian Libraries’ website.)

Hokusai’s images were adapted in etchings created by Bracquemond and the resulting prints on paper were cut out and applied directly to the earthenware forms to be fired in the kiln and then hand-painted. All the pieces in the set have motifs arranged in groups of three with a large subject connected to two smaller subjects referencing the pictorial genre of kachō-ga.

Félix Bracquemond, Fish Patterns for the Service Rousseau, 1866, etching. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Félix Bracquemond, Soup plate (part of a set of three), 1866-1875, creamware. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Commissioned by dealer and publisher Eugène Rousseau the set was produced specifically with the 1867 Paris Exposition Universelle in mind and was also shown at subsequent fairs in Paris, Vienna and London. The set was extremely well-received by the public and collectors. Indeed, it was so popular that the design was continuously manufactured from 1866 to 1940.

For its French audience, the set represented a novel design that was appealing not only for its combination of styles but also for its adaptability which permitted consumers across the bourgeoisie and aristocracy to use the set in ways that suited their personal tastes. Bracquemond and the Rousseau set contributed in part to the revival of French printmaking and ceramics. This sense of revivalism happening in France intertwines with a similar ethos in Meiji Japan and its various efforts to present itself among its international peers as a modern nation.

Selected Sources:

“Japonisme.” Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/jpon/hd_jpon.htm.

“Hokusai’s Manga.” Princeton University Library, http://library.princeton.edu/news/2014-12-16/hokusai%E2%80%99s-manga.

“Le Japonisme.” Musée des Arts Décoratifs, https://madparis.fr/francais/musees/musee-des-arts-decoratifs/parcours/xixe-siecle/le-japonisme/.

Bracquemond, Félix. Footed Dish, 1866-1867. Philadelphia Museum of Art, http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/139149.html.

Brink, Emily. “Touch Codes and Japanese Taste: The Material Experience of Félix Bracquemond’s Service Rousseau.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, vol. 18, no. 1, 2018, pp. 108-124.