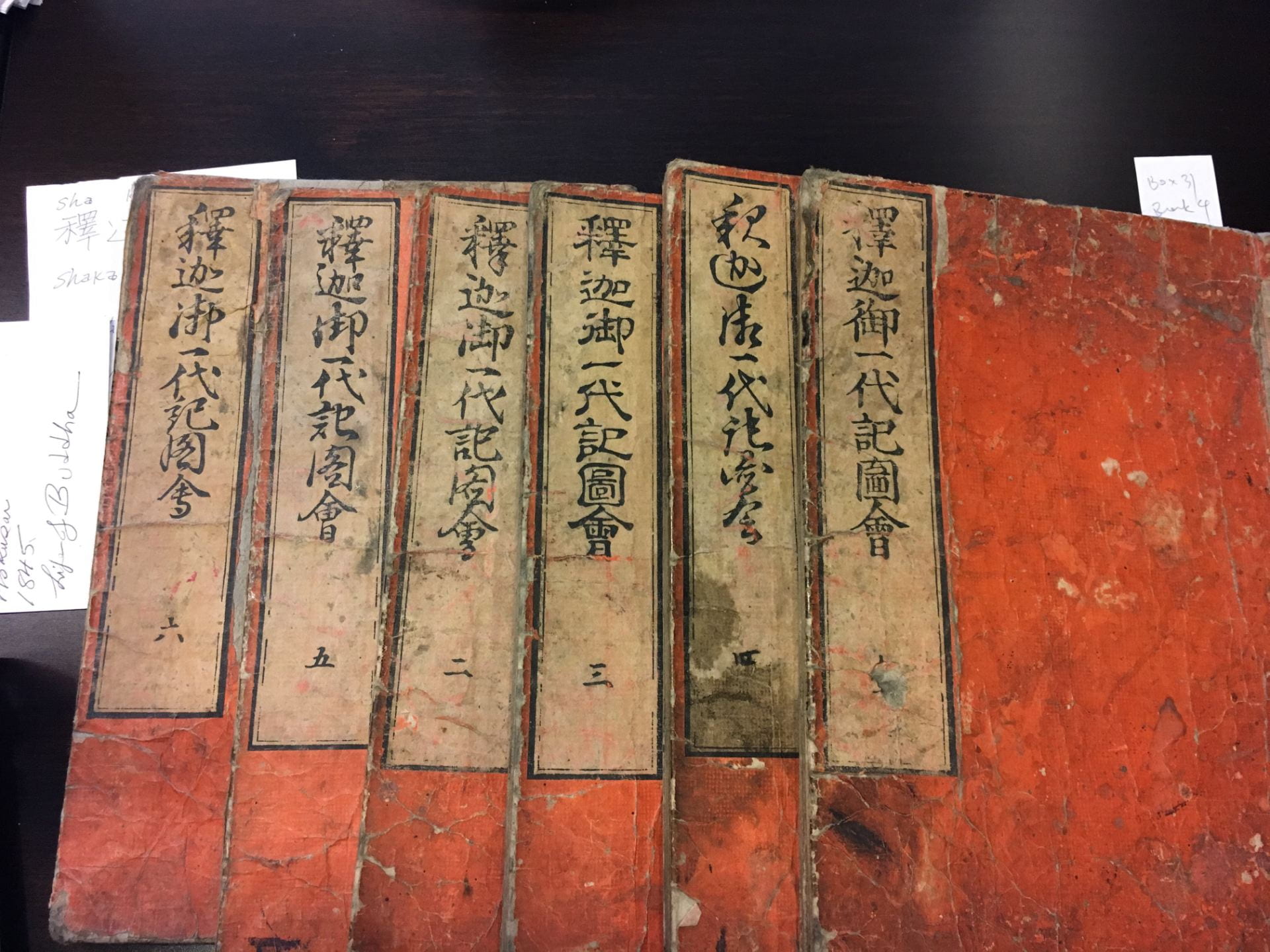

Title: Shaka go-ichidaiki zue 釈迦御一代記図絵 (Illustrated Record of the Life of Śākyamuni), six volumes

Date: 1845, fourth month

Medium: woodblock print, ink on paper

Dimensions: 24.9×17.8cm

Compiler: Yamada Isai 山田意斎 (1788–1846)

Illustrator: Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾北斎(1760–1849)

Preface: Daikō Sōgen大綱宗彦 (1772–1860)

Publishers:

Kyōtō Echigoya Jihee京都 越後屋治兵衛

Edo Yamashiroya Sahee江戸 山城屋佐兵衛

Ōsaka Kawachiya Mohee大阪 河内屋茂兵衛

Arthur Tress Collection (Hokusai 50)

https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977881052803681

See digital images here

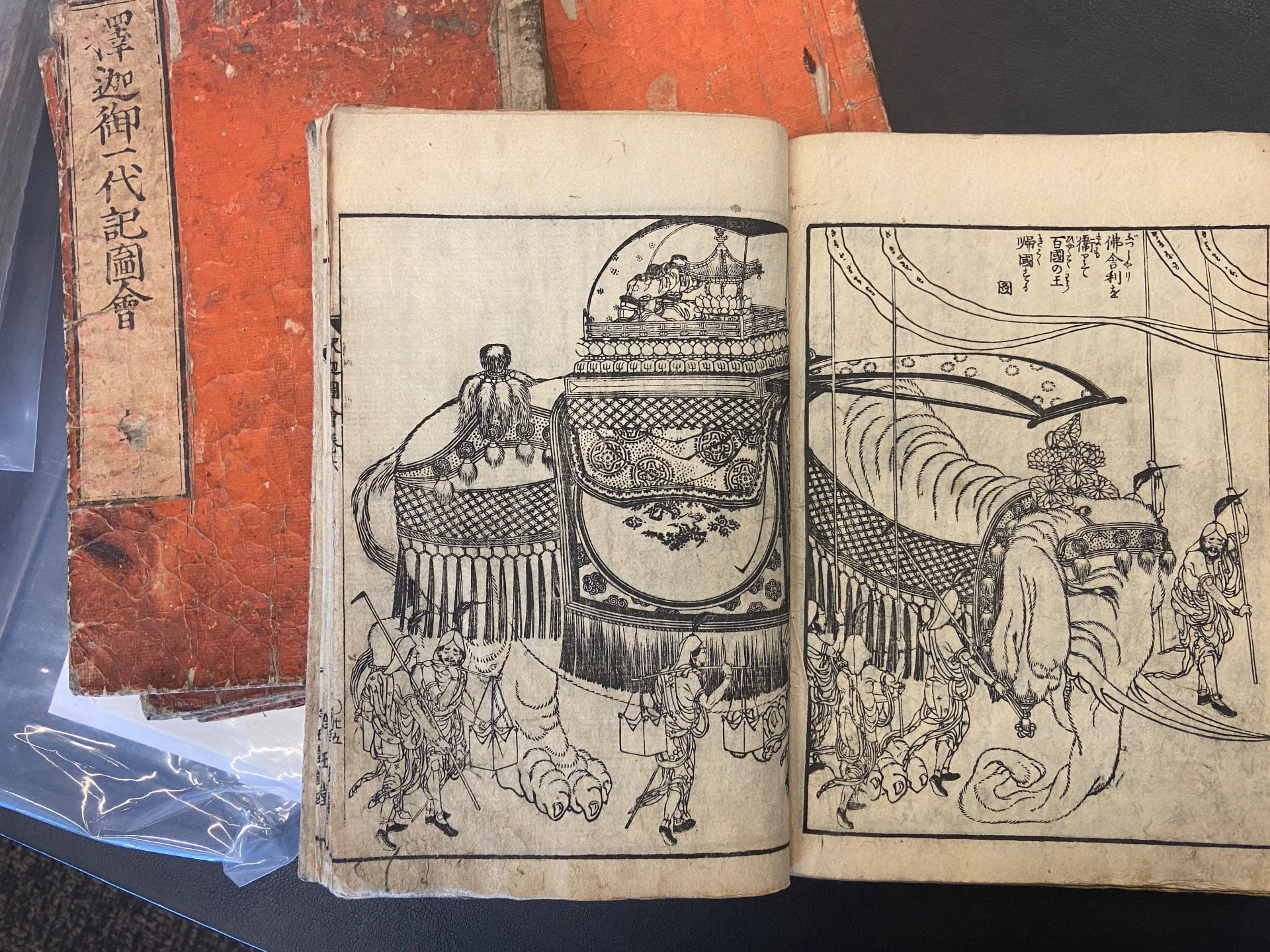

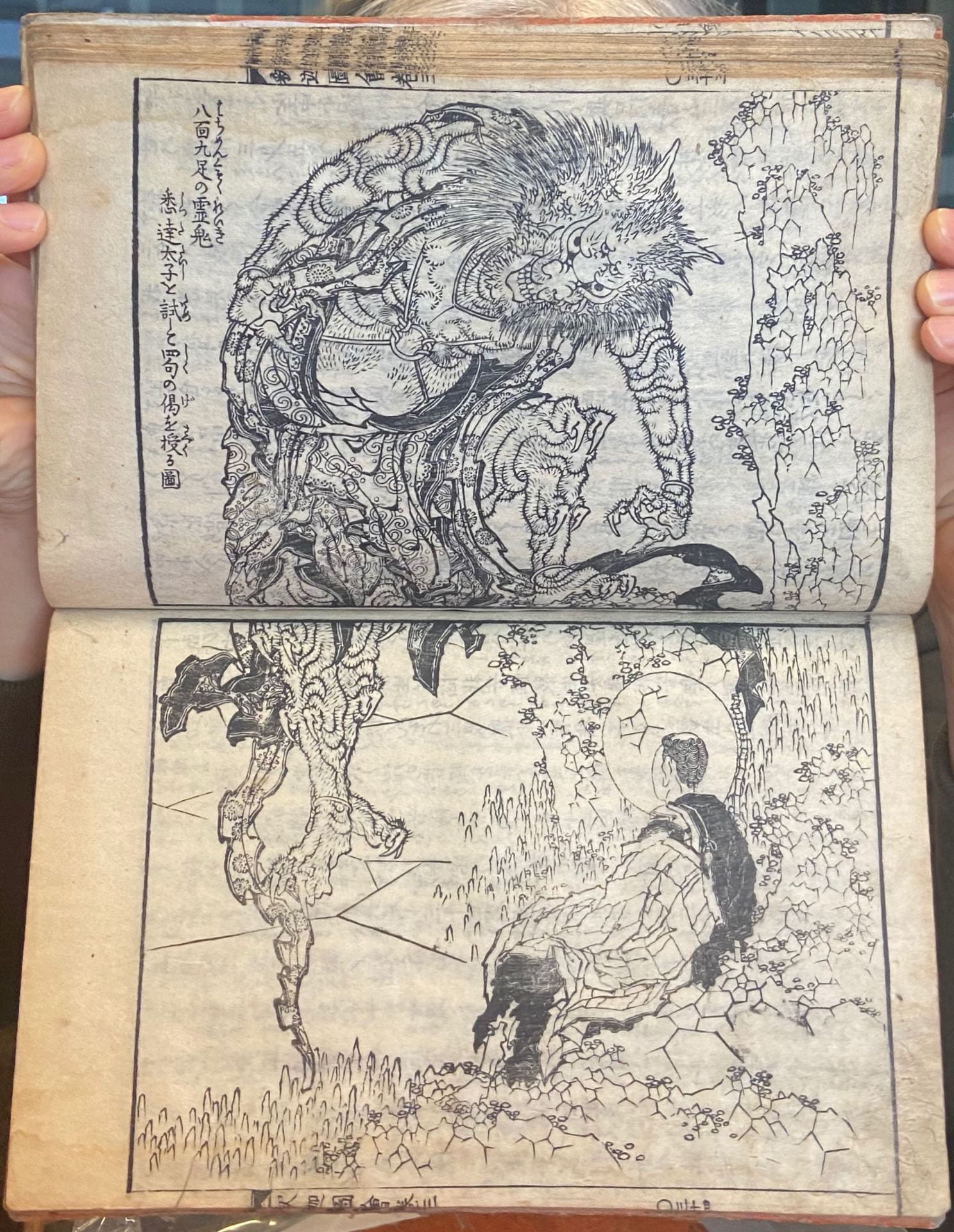

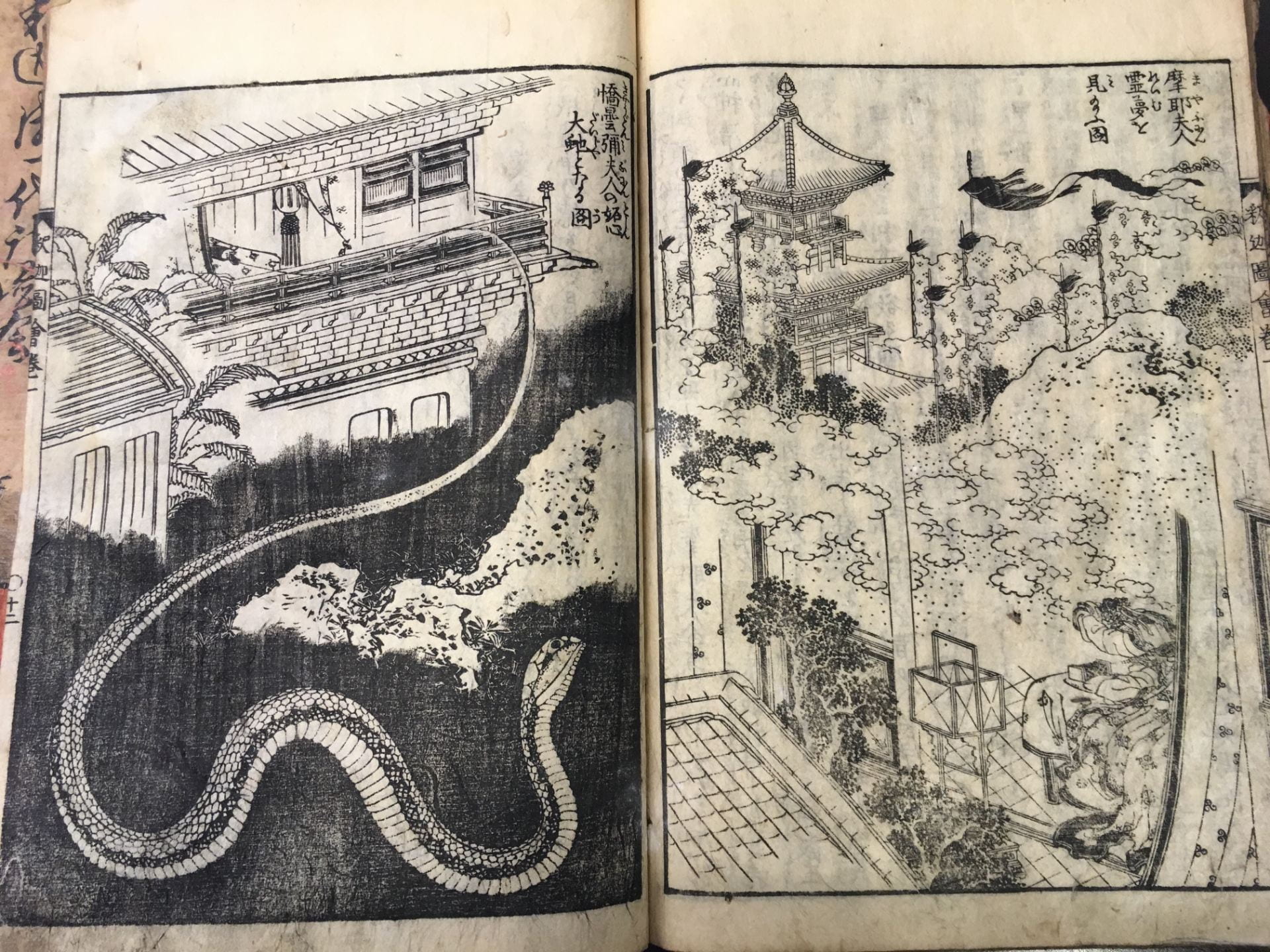

In 1845, Illustrated Record of the Life of Śākyamuni was compiled by Yamada Isai (1788–1846) and illustrated by eminent artist of painting and print, Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849). Executed near the end of both Isai and Hokusai’s lives, the book contains thirty-two monochrome illustrations of episodes from the Buddha’s life story in six volumes. The book begins in the Indian kingdom of Kapilavastu before the birth of the Buddha with an illustration of the court of the Buddha’s father, King Śuddhodana, and ends after the Buddha’s death, with an illustration of the distribution of the Buddha’s relics.

Across Asia, images of the Buddha’s life have shared common narrative structures and iconographical conventions for centuries. There is no single, authoritative textual source for the story of the Buddha’s life, and, historically, visual narratives have been structured around several well-known canonical episodes, spanning the Buddha’s birth as Prince Siddhārtha, through his renunciation of worldly attachments, ascetic practice, attainment of enlightenment, and final death. Although these narratives were eventually standardized into recognizable templates, comprising eight or twelve major episodes, they could also be altered creatively to specific contexts, either by adding new episodes, or by extending the narrative beyond the death of the Buddha.

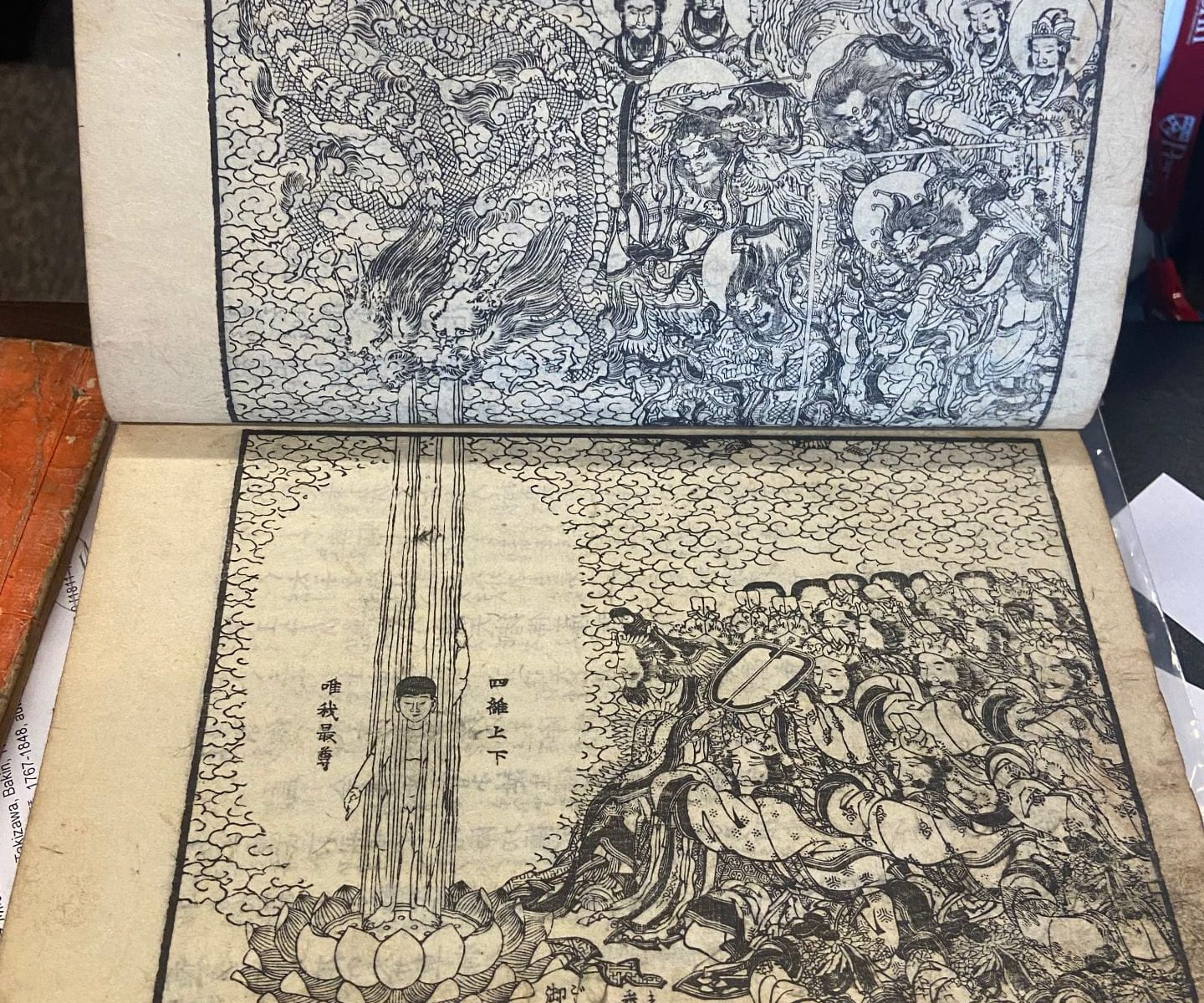

The relationship between Illustrated Record of the Life of Śākyamuni and the canonical episodes of the life of the Buddha is akin to that between historical fiction and history. Hokusai’s illustrations, in particular, give precedence to creative additions over canonical staples. The book, for example, does not illustrate the Buddha’s death, and, instead, focuses narrative attention on the machinations of jealous relatives, otherworldly skirmishes, and scenes of hell. The double-page illustration here depicts the episode of dramatic intrigue that concludes volume 1. The right-hand illustration depicts the canonical episode of Buddha’s conception, as the Buddha’s mother, lady Māyā receives a dream of her pregnancy. In the left-hand illustration, however, Māyā’s sister, Gotamī—who is conventionally depicted as benevolent aunt to the Buddha—is recast as a jealous foil, who, consumed by envy, is transformed into a giant snake. This aspect of the narrative derives not from stories of the life of the Buddha, but rather from the story of Lady Xi 郗 (468–499), would-be empress of the Chinese Liang dynasty (502–577).[1]

Additional Impressions:

- Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties [織田/2/14174 (2101005041–2101005046)]

https://opac.tobunken.go.jp/search/detail.do?method=detail&bibId=900AA16695&bsCls=0

- Okaya Bunko, Nagoya University Library [913.56/Ko/岡谷文庫‐902 (10091278–10091283)]

https://kotenseki.nijl.ac.jp/biblio/100272744

- Yoshida-South Library, Kyoto University

- Tohoku University Library

- Kyushu University Library

- Rikkyo University Library

- Kwansei Gakuin University Library

- Bukkyo University Library

- Kobe University Library for Social Sciences

- General Library, University of Tokyo

- Senshu University Library

- Nara Prefectural Library & Information Center

Selected Reading:

Asano Shūgō 秀剛浅野, ed., Hokusai ketteiban 北斎決定版 (The Definitive Hokusai) (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 2010), 72.

Timothy Clark, ed., Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave (New York: Thames & Hudson, in collaboration with the British Museum, 2017), 252, no. 158.

Posted by Bryce Heatherly

Spring 2021

[1] Across various recensions of her story, which have circulated for centuries in East and Central Asia since in vernacular tales, Buddhist proselytizing literature, and in the ritual text Merciful Penitence of the Ritual Area (慈悲道場懺法), Lady Xi is said to have transformed into a huge snake due to her extreme jealousy. See Rostislav Berezkin, “Narrative of Salvation: The Evolution of the Story of the Wife of Emperor Wu of Liang in the Baojuan Texts of the Sixteenth-Nineteenth Centuries,” Chinese Studies 37, no. 4 (2019).