Anonymous

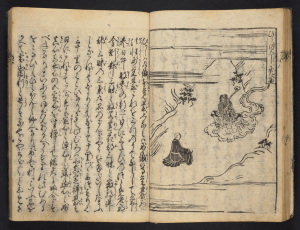

Woodblock for Shaka hassō monogatari 釈迦八相物語

Edo period (1603-1868), [1666]

Woodblock

22.3 x 35.1 cm

Anonymous

Shaka hassō monogatari 釈迦八相物語

Volume 4 (of 8)

Edo period (1603-1868), [1666]

Woodblock printed book; ink on paper

25.5 x 18.2 cm

The ability to capture the hand of the calligrapher and artist alike made woodblock the preferred printing medium in Edo-period Japan. The raw material was key to this process: high quality cherrywood (yamazakura) blocks were supple enough to be carved without splintering or fraying yet durable enough to stand up to hand printing impressions that could number in the thousands. Obtaining this raw material constituted a significant challenge. Trees in climates too cold or too hot produced wood that splintered easily. The wood needed to be prepared through a seasoning process before being used for printing blocks. Good blocks, like this one, were well worth the significant investment and effort, and skilled carvers copied layouts to transform planks and capture the lyrical and expressive qualities of the brush.

The Tress collection includes a block made for two folios from the Shaka hassō monogatari (Tale of the Eight Phases of Shakyamuni), first printed in 1666. The book tells the story of the eight phases of the life of Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha. The collection also includes a woodblock for folios from the fourth volume of this title, offering the rare opportunity to compare block and printed book. The scene shown in both is an episode from the fourth phase of Shakyamuni’s journey, when he renounced the world to become an ascetic. One should be keen to note, however, how the woodblock differs from the opening. Woodblock printing required the carver to render the designs in reverse so that when printed, the text and image would be right way around. Books bound in the pouch or bag binding technique (fukurotoji), like this one, were made by folding sheets of paper and binding the cut edge in the interior of the book. The image showing Shakyamuni’s renunciation is carved on the right side of the block and the text for the preceding page on the left side; when printed, the sheet of paper would be folded and bound, with the two parts of the woodblock providing content for the verso and recto of the folio sheet. This woodblock is also carved on its reverse side, but the text there is from another volume from the same set.

Woodblocks were mobile objects in the Edo period, frequently traded and sold amongst publishers, with each new owner gaining full publishing rights for the block and its contents. This was an advantageous arrangement for both sellers and buyers: sellers could recoup precious capital while buyers could obtain second-hand blocks to expand their publishing repertoire or capitalize on an unexpected hit.

The survival of this woodblock in excellent condition is remarkable. As wooden objects, blocks are susceptible to degradation as well as damage by insects. Many blocks were victim to the fires that were an all-too-common occurrence in cities. Furthermore, the price of high quality cherrywood often led publishers and block carvers to repurpose existing woodblocks. Planing a woodblock down would destroy the image but provide a new blank slate, allowing one block to live several lives and be part of multiple different works before ultimately becoming too thin and fragile for additional printing.

Nicholas Purgett

Selected Readings:

Hioki, Kazuko. “Japanese Printed Books of the Edo Period (1603-1867): History and Characteristics of Block-Printed Books.” Journal of the Institute of Conservation 32, no. 1 (2009): 79–101.

Salter, Rebecca. Japanese Woodblock Printing. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2001.

Sasaki, Shiro. “Materials and Techniques.” In The Hotei Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints., edited by Amy Reigle Newland, 1:323–50. Amsterdam: Hotei, 2005.