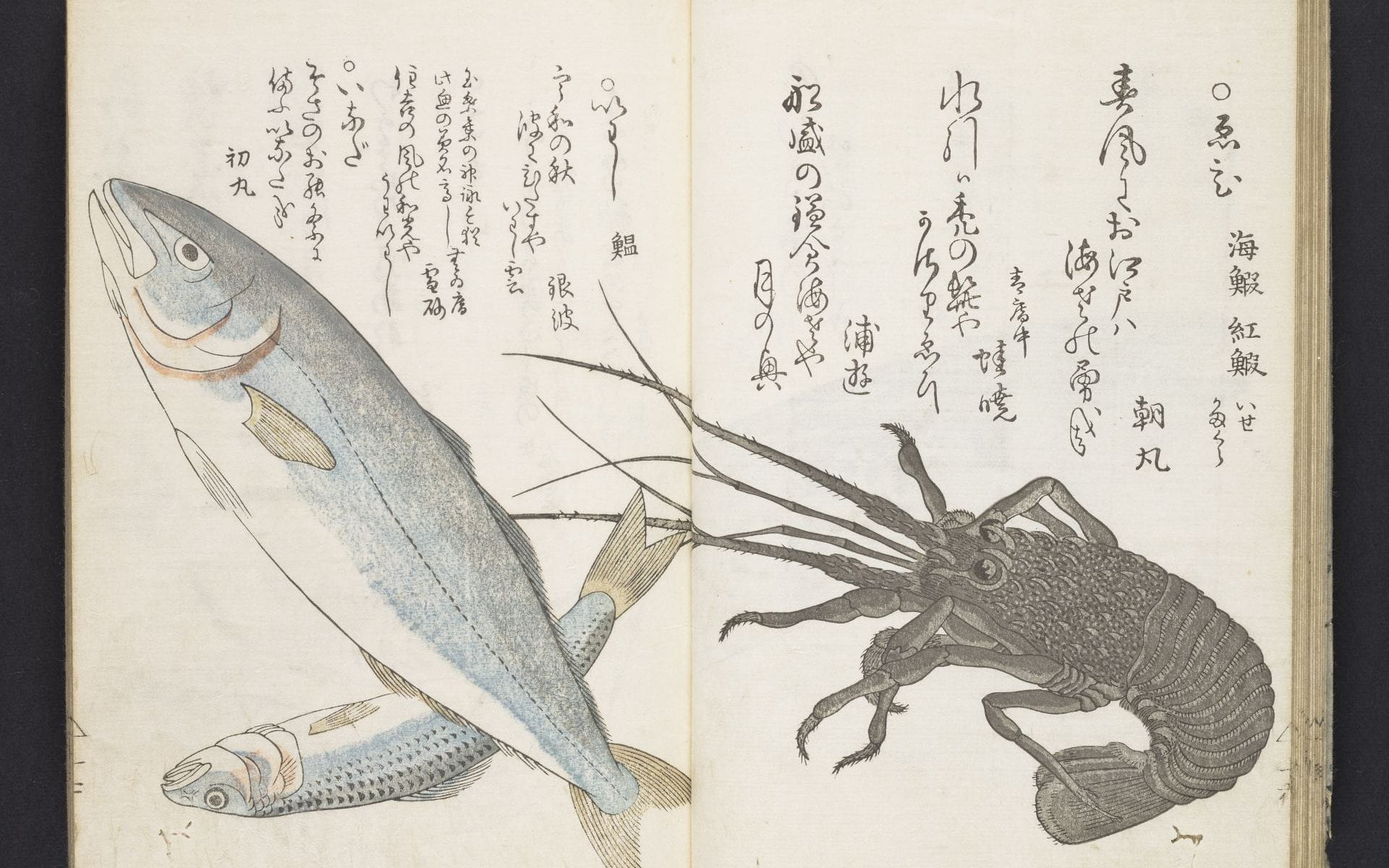

Artist: Katsuma Ryūsui 勝間竜水 (1711-1796)

Title: Umi no sachi 海幸

Date: 1762

Medium: Woodblock printed, ink and color on paper

Gift of Arthur Tress, Arthur Tress Collection of Japanese Illustrated Books, Ryūsui 1

Umi no sachi, or Treasures of the Sea, is an extraordinary two-volume book of poetry matched with lavish color-printed illustrations of fish. Produced in large format on an unusual theme, this project was probably the private production of a poetry circle, rather than a commercial publication.(1) At its core, the work is a compilation of haikai poems. Yet its unusual theme, exceptional printing, and fascinating, deftly executed pictures defy such easy classification.

The first volume opens with a preface by the esteemed Baba Songi (1703–1782), a leading practitioner of haikai poetry in the mid-eighteenth century. Next come three further introductory texts: one by the book’s editor and fellow poet Sekijukan Shūkoku and two by artist Katsuma Ryūsui. Shūkoku’s preface outlines the allusion present in Umi no sachi’s title: the ancient tale of two brothers, Umi no Sachi Hiko (Prince Luck of the Sea) and Yama no Sachi Hiko (Prince Luck of the Mountain), found in the early chronicle the Kojiki (A Record of Ancient Matters, 712).(2) It was typical in the period for such prefaces to provide highly elevated or literary references, such as this classical text, no matter how mundane the content. In this case, it provides the justification for the aquatic theme to follow.

In the main text of the book, each page opening reveals new variety of fish, splendidly printed in color and accompanied by poems for each type. With more than one hundred species represented, the book presents a veritable catalogue of the bounty of the sea, rivers, and lakes. These aquatic creatures range from established delicacies like sea bream, tuna, octopus, eel, and various kinds of shrimp to more exotic subjects like the whale—so vast it is represented by the inky darkness of a page printed in reverse—and the semi-mythical minogame—a hairy-backed turtle and symbol of longevity. Every illustrated fish is also identified by name, sometimes with several Chinese variations, as if to imitate the conventions of natural history texts.

One of the things that makes Umi no sachi so significant in the history of Japanese print culture is that its abundant color printing predates the development of full-color nishiki-e in sheet prints by three years. Every illustration uses at least two printed colors in addition to black; most illustrations display up to five or even six colors. And though profuse and elaborate, the color printing in this book is often quite subtle. A fish might be depicted in three shades of grey, rather than boldly saturated with contrasting colors. Furthermore, each fish, mollusk, or crustacean is approached with a degree of naturalism by artist Ryūsui. Their sometimes startling morphological verisimilitude signals the growing interest in the period in honzōgaku, or natural studies.

Highly appreciated in the period, Umi no sachi was reprinted multiple times by successive publishers. The Tress copy of Umi no sachi comes from the first printing, published by Kameya Tahei in the second month of 1762. These early printings rank among the very finest examples of early multiple color woodblock printing in Japan, enhanced with special techniques like applications of mica which make the fish seem to shimmer on the page.

(1) Their poems and sobriquets appear throughout the book, and though most of these poets are unknown today, it has been speculated that some of the contributors may have been high-ranking samurai See Kira Sueo, “Tashokuzuri ebaisho ni tsuite,” 16.

(2) Both the Kojiki and Nihon shoki contain versions of this story. For an English translation of the story based on the Kojiki, see Ō and Heldt, The Kojiki, 53-60.

Other collections:

Pulverer Collection, Freer Gallery of Art

Posted by Jeannie Kenmotsu, April 6, 2022