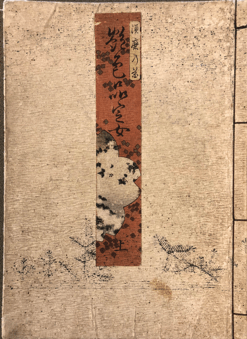

Artist: Utagawa Sadahide 歌川貞秀(Japanese, 1807-1879?)

Date: 1862-1865

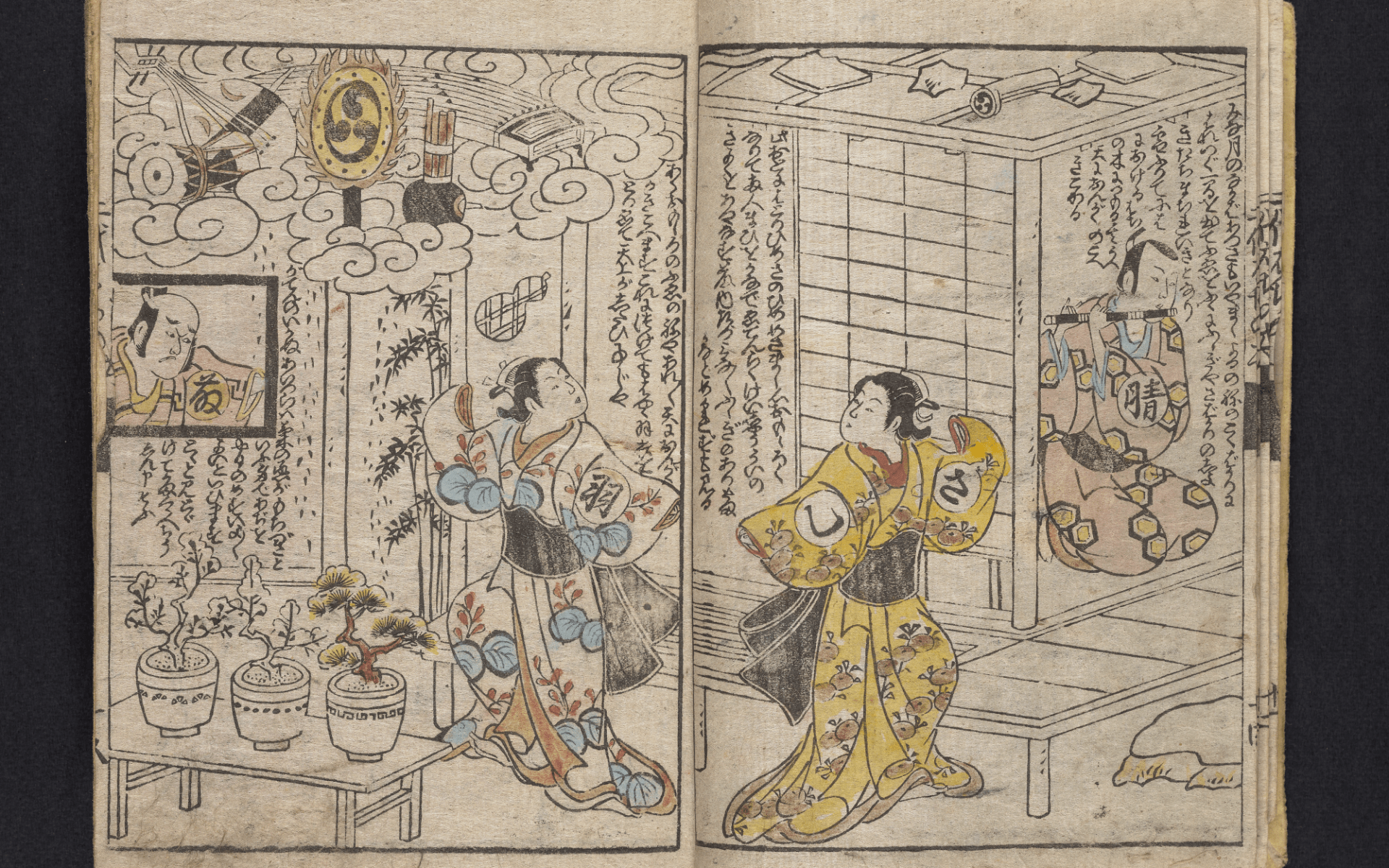

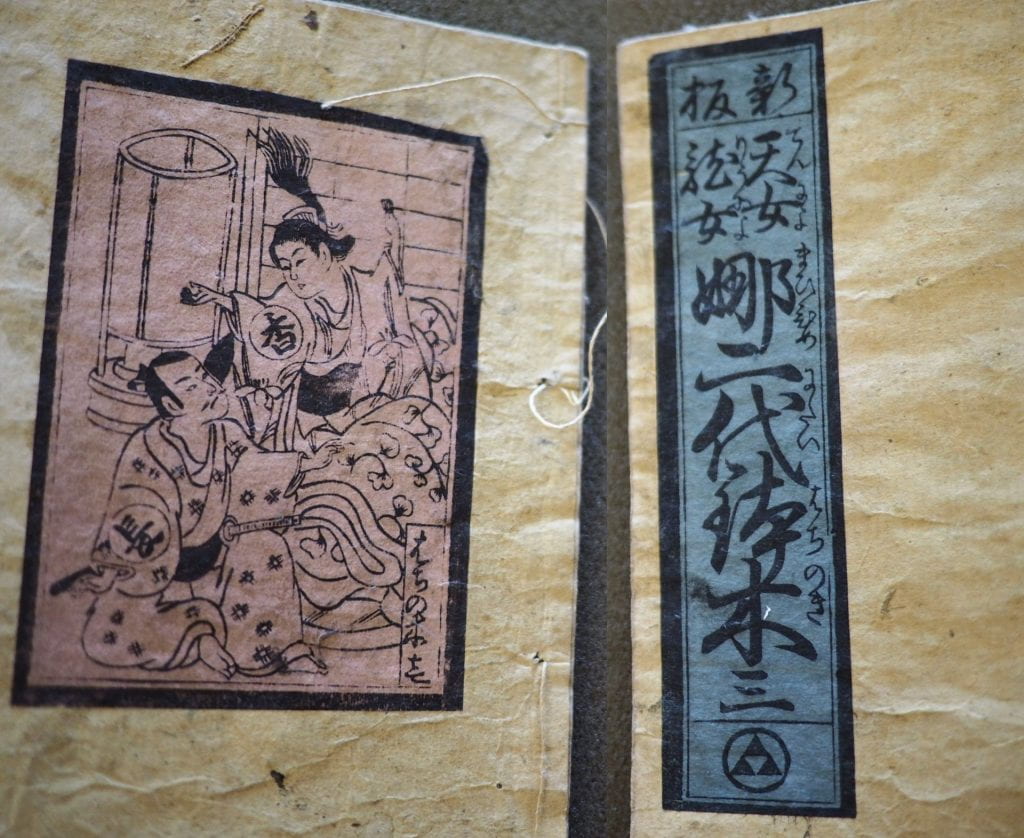

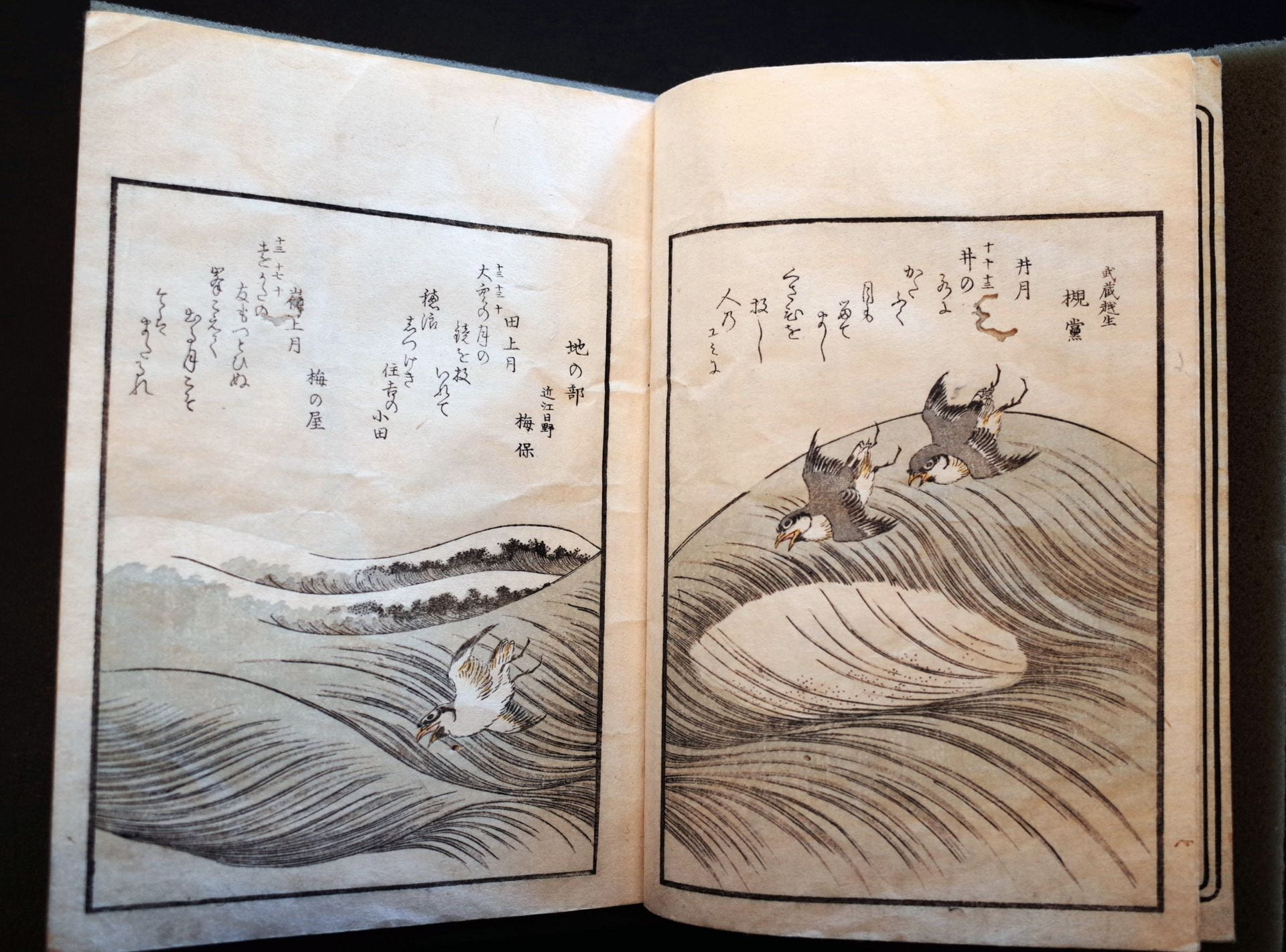

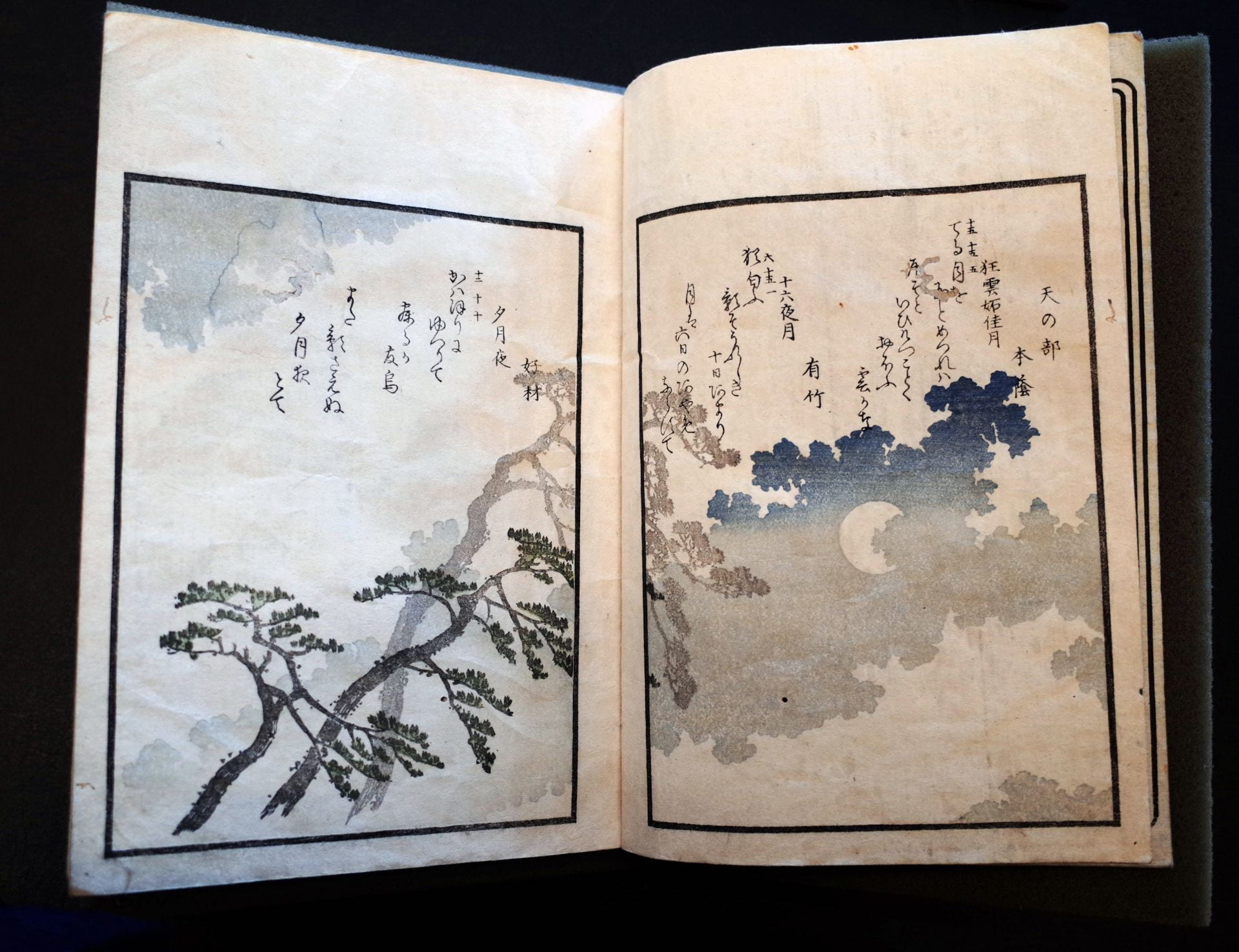

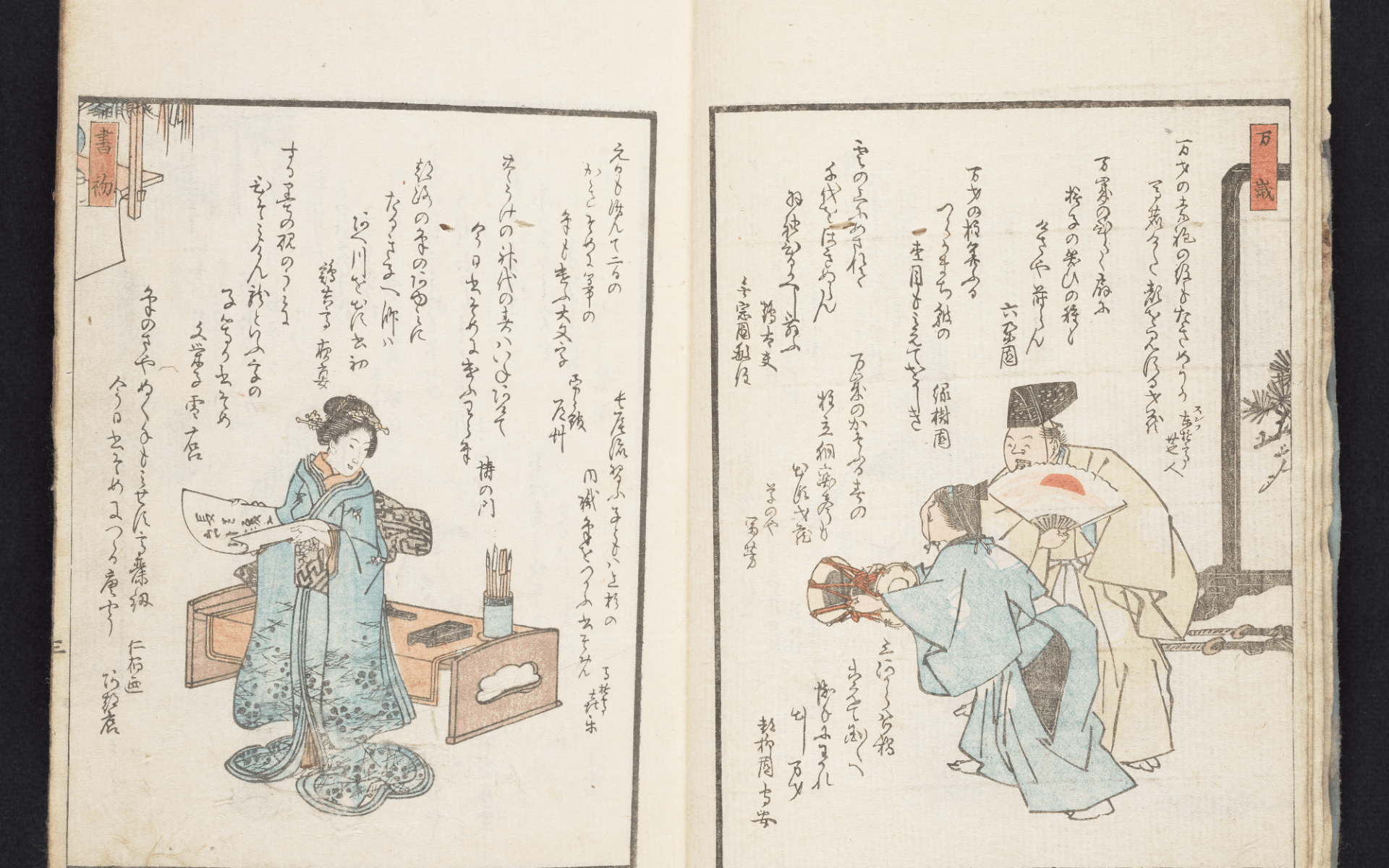

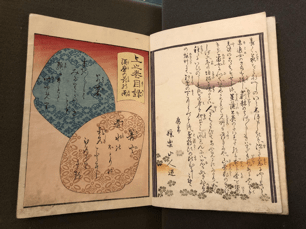

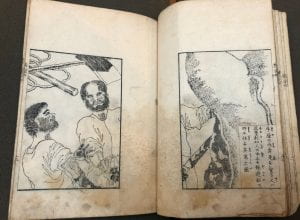

Medium: Black-white woodblock printed book; ink on paper

Description: 6 volumes; 24.5cm; fukurotoji (pouch binding)

Publisher: Unknown

Call Numbers: Arthur Tress Collection. Box 2, Item 19.

Arthur Tress Collection. Box 55, Item 15.

Arthur Tress Collection. Box 65, Item 10.

Gift of Arthur Tress.

This is an illustrated book consisting of 6 volumes, depicting the foreigners and their lifestyles in Yokohama, in its early years of the Yokohama Port opening.

In 1859, a year after an international trade treaty was signed between Japan and the United States, followed by other similar agreements with England, Netherland, France and Russia, a sleepy fishing village of Yokohama was selected to open its port for international trade and commerce. Japanese merchants from nearby regions flocked to the port to take advantage of this new business opportunity, exporting raw silk, tea, and copper. With foreigners from the United States and European countries pouring in, Yokohama became an international city overnight.

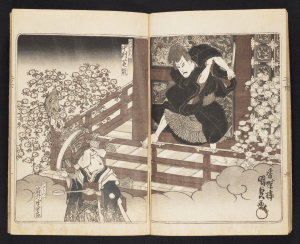

As the news of foreign lifestyles reached further inland, Japanese interest and curiosity towards foreigners grew. Seeing an opportunity in the people’s interest in the lives of the ‘others,’ business-minded publishers in Edo sent Ukiyo-e artists into Yokohama to make prints depicting the new and exciting lives of the foreigners. This type of journalistic prints that became popular beginning in 1860, eventually came to be known as “Yokohama-e” or “Yokohama Nishiki-e,” and it played an important role in informing Japanese as they prepared to take in the influences of the foreign culture.

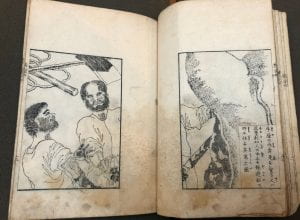

Yokohama Kaikō Kenmonshi was published in 1862, during the peak of Yokohama-e’s popularity. There are only a few other examples of Yokohama-e published in book format, as the majority of it was done in color prints. In this book, the artist/author Sadahide illustrates not only foreign people and objects they brought in but captures scenes of lively interactions and behaviors of the foreigners. Although this book mostly consists of illustrations, there is a significant amount of journalistic writing by Sadahide. There is a depiction of the impromptu dance party amongst the foreigners, what children played with and how they behaved, and description of work performed by the servants and what they ate, to give a few examples. There is even a detailed account of a quarrel he encountered at a bar between the Japanese bartender and a foreign drunkard who demanded top-shelf liquor without having enough money for it. Sadahide, unlike many other Yokohama-e artists of the time, visited Yokohama often to observe and interact with people of various backgrounds to produce this work.

Each of the 6 volumes starts with a full page of the preface, which explains the topics covered in the specific volume. The preface is followed by 13-15 spreads of illustrations with brief descriptions, and each volume concludes with 10-12 pages of texts, describing what Sadahide has seen, overheard and encountered, along with his interpretations and opinions on the matter.

What is most notable and touching about this work is his appreciation and respect for people, no matter what countries they may be from. Sadahide captures all the uniqueness and differences he sees in foreigners and the things they do, but he also captures many similarities between himself (Japanese) and the foreigners throughout the text.

Yokohama Kaikō Kenmonshi became an instant bestseller, and there is no doubt that it had an impact in opening up Japanese minds toward foreign culture as they were getting ready to adopt western ideas in a transitional time. It will continue to be a valuable source not only for art historians or book historians, but also for scholars researching topics such as foreign influences on Japan, international trade and commerce, or history of slaves.

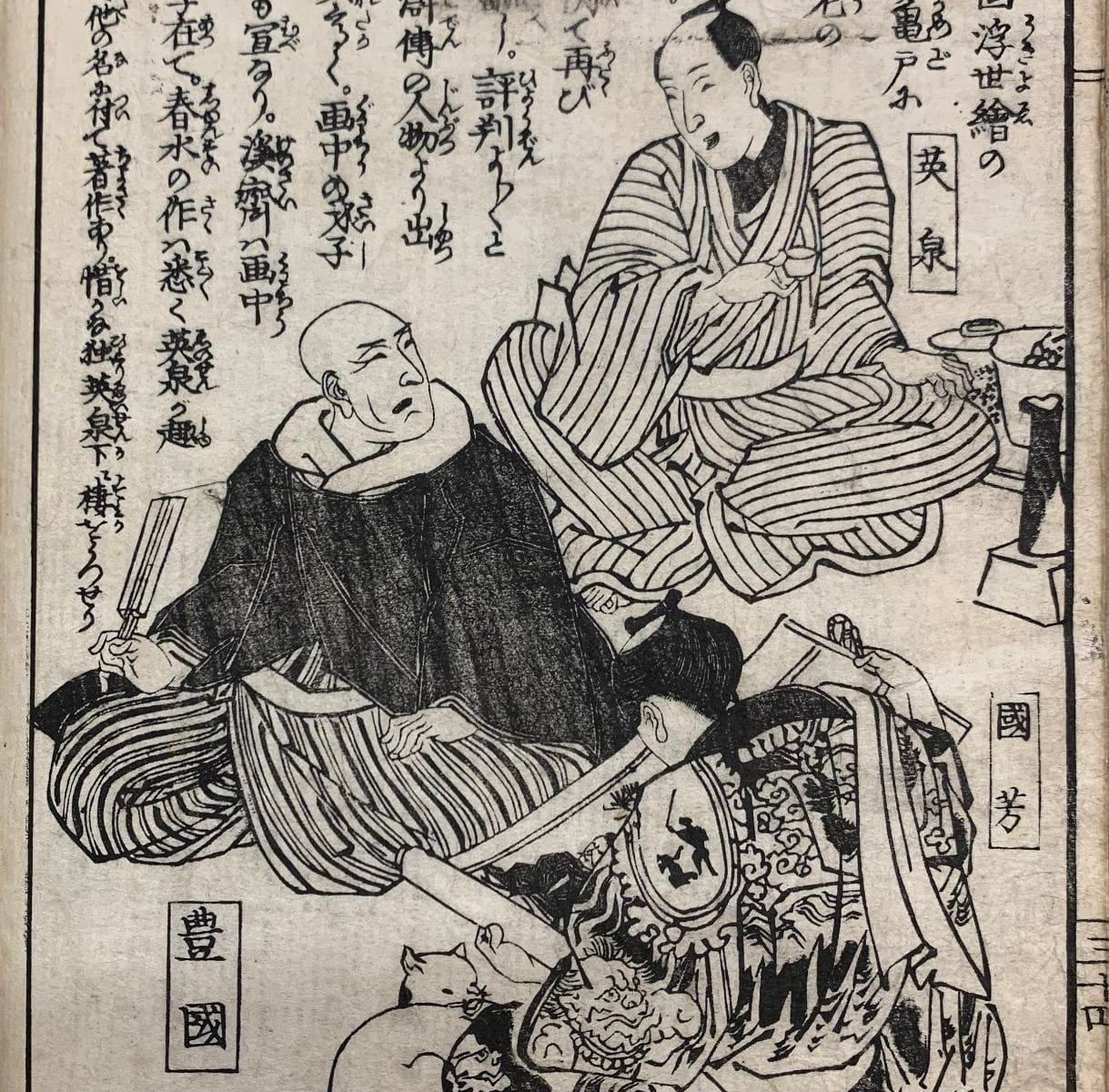

Utagawa Sadahide歌川貞秀, also known as Gountei Sadahide五雲亭貞秀, Hashimoto Gyokuransai橋本玉蘭斎, Gyokuransai Sadahide玉蘭斎貞秀 or Gyokuō玉扇, was born in 1807 (Bunka 4) in Fusa providence (modern-day Chiba) as Hashimoto Kenjiro橋本兼次郎. Sadahide studied under the master Utagawa Kunisada, and he is said to be the most successful pupil of Kunisada. Sadahide’s illustrations were first published in 1821 (Bunsei 4) when he was 14 years old, for a kokkeibon published by Takizawa Bakin’s apprentice.

Sadahide is most known for his Yokohama-e, and considered to be the pioneer of the genre, as the first known print published of Yokohama after its port opened was Sadahide’s Kanagawa Yokohama shin kaikō zu 神奈川横浜新開港図(Newly-opened Port of Yokohama, 1860).

Sadahide was also known for his panoramic landscape and cityscape paintings done in birds-eye-view. Sadahide traveled on foot for days to research the land before he went to work on his large-scale maps.

In 1866, Sadahide, along with 11 other Ukiyo-e artists exhibited their work at the Paris International Exposition and received Legion d’Honneur.

Sadahide continued to work until a few years before he died in 1878 or 1879, when he was 71 or 72 years old.

Other Impressions

The British Museum

Freer/Sackler – The Gerhard Pulverer Collection

Nagoya Hōsa Library

The Met Museum

Waseda University Library

Selected reading/bibliography

Kida Jun’ichirō. 紀田順一郎. “Yokohama Kaikō Jidai no Hitohibo.” 横浜開港時代の人々. Kanagawa Shinbun Sha, 2009.

Munakata Morihisa. 宗像盛久. “Yokohama Kaika Nishiki-e o Yomu.” 横浜開港錦絵を読む. Tōkyō-Dō Shuppan, 2000.

Takumi Hideo. 匠秀夫. “Yokohama Nishiki-e to Gountei Sadahide” 横浜錦絵と五雲亭貞秀. In Nihon no Kindai bijutsu to Bakumatsu. 日本の近代美術と幕末, p.95-184. Chūseki Sha, 1994.

Sugimoto Fumiko and Michael Burtscher. “Shifting Perspectives on the Shogunate’s Last Years: Gountei Sadahide’s Bird’s-Eye View Landscape Prints.” Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 72 no.1, 2017, p.1-30.

Posted by Eri Mizukane

March 25, 2020