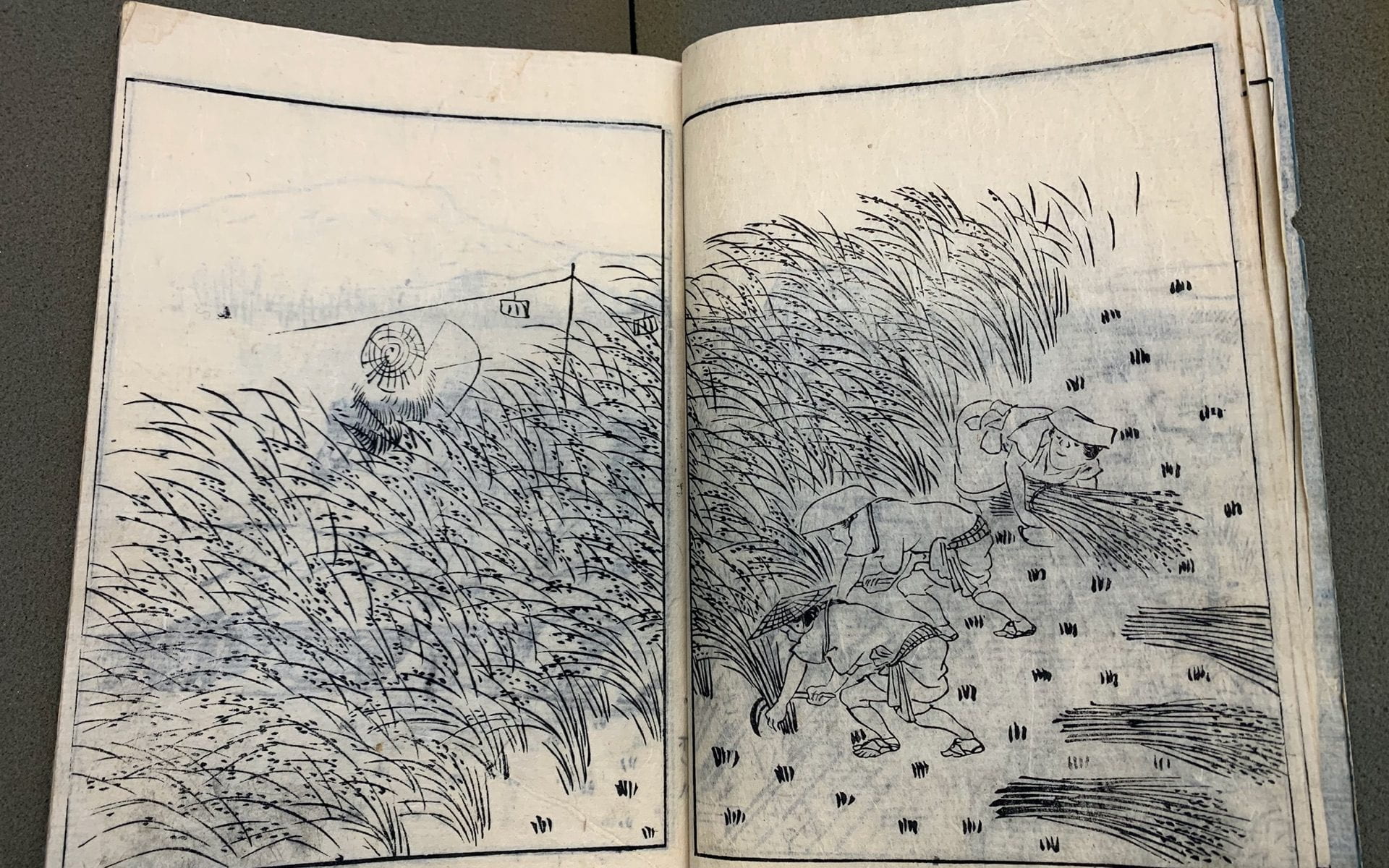

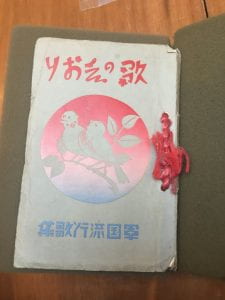

Artist: Unknown

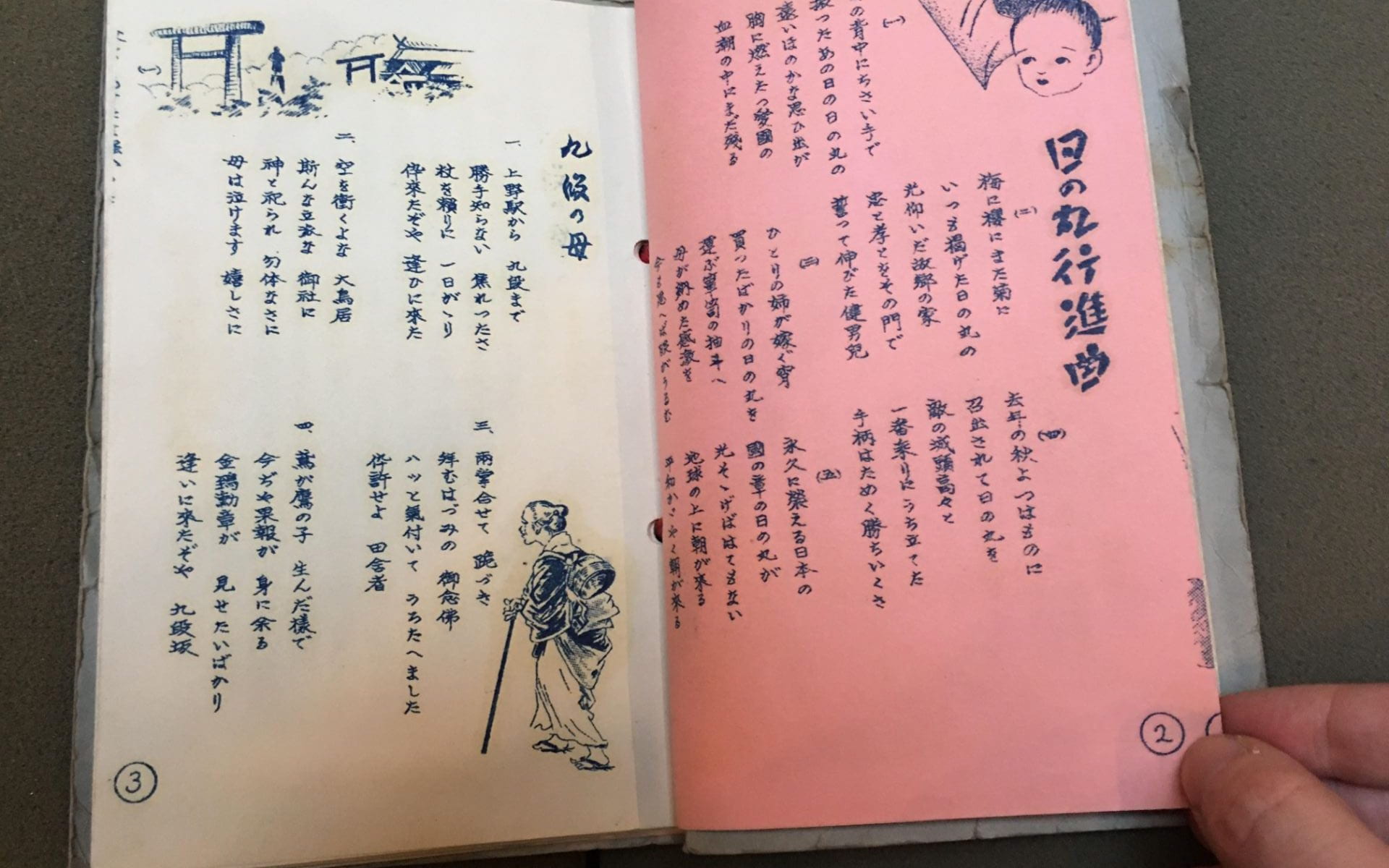

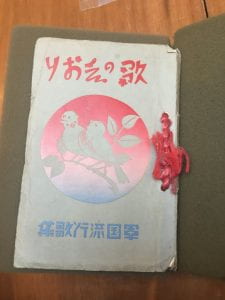

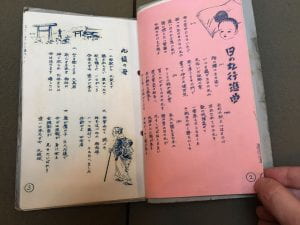

Title: 歌のしおり帝国流行歌集 (Collection of songs popular in the Empire)

Date: 1944

Medium: Mimeograph, ink on paper

Gift of Arthur Tress, Arthur Tress Collection. Box 45, Item 12

(https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977502355903681)

This collection of songs praising the Imperial Japanese Empire is from the Tule Lake Segregation Center, one of the main camps used by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to house Japanese citizens classified as potential threats to the U.S. Government. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, allowing the U.S. Government to relocate and incarcerate Japanese American citizens and residents en masse. Of the camps designated to be used for internment, Lake Tule was reserved for internees who were deemed “disloyal” based on their response to the infamous loyalty questionnaire. According to Jane Dusselier, “internees at Tule Lake lived under the strictest security restrictions of all the camps because, in Fall 1943, the War Relocation Authority designated Tule Lake the segregation center for ‘troublemakers’.”[1] However, as Brian Hayashi notes, the loyalty questionnaire was confusingly worded, and many internees who ended up at Lake Tule simply did so to follow family members who had already been sent there.[2]

Given the camp’s strictness and special designation, the production and existence of this collection of songs seems all the more remarkable. The production of arts, crafts, and materials such as this booklet were widespread within the relocation camps, to the extent that Sam Hayakawa would cite them in 1981 as evidence that the camps were “trouble free and relatively happy.”[3] As Jane Dusselier notes, such a reading of the “forced leisure” in internment camps is problematic “because it suggests that internee artwork is evidence of humane treatment.”[4] The charged content of the material in this book, replete with patriotic and militaristic songs that were popular in the Japanese Empire at the time, suggests it served a political function in the context of the camp itself. This may show the complex dynamics of Tule Lake’s internees at the time. According to Heather Fryer, the shift in the camp’s population in 1943, and its new designation as a center for “disloyal” Japanese Americans produced political tensions between different internee groups: as she writes, “housing shortages, restrictive regulations, and the absence of jobs for new arrivals stoked resentments between the new segregants and the established, ‘loyal’ Tuleans,” from 1943 onward.[5] Ongoing tensions between the camp administrators and newer arrivals spurred the creation of anti-administration extremist groups such as the Sokuji Kikoku Hoshi Dan and the Hokoku Seinen Dan in early 1944, which took a hard line against the U.S. Government and espoused an avowedly pro-Japanese Empire politics.[6] These actions, in turn, prompted the U.S. Congress to pass Public Law 405, which allowed Japanese Americans to renounce their citizenship and be repatriated to Japan. According to Fryer, “Anti-administration factionalists,” within the camp used the law as a pretext to force “unwilling Tuleans to renounce as a political stand.”[7]

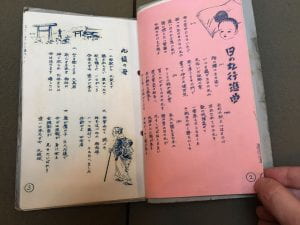

Given the date of the booklet’s production, it is likely it was created in the midst of this political turmoil. At one point, tensions between pro and anti-administration internees reached such a height that one internee, Yaozo Hitomi, was fatally stabbed for working with camp administrators. Its existence may also attest to the camp administration’s relative lack of knowledge and comprehension of internal politics between different groups of internees. Most of the songs collected were major hits in Japan in the late 1930s with themes of love, family, and patriotism. The first song in the booklet, Aikoku shinkō kyoku (Patriotic March) for instance, was released at the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and sold over 1 million copies by 1938.[8] Yet despite the overwhelming presence of songs about patriotism and war, some of the songs collected, such as Otoko no junjō (A man’s pure feelings, 1937) are slow love ballads rather than patriotic marches. One song, the 1940 hit Dare ka kōkyo o omawazaru (1940), a song about longing for one’s hometown, was actually banned at one point on the Japanese mainland for fear it would cause factory workers in cities to lose morale.[9] This diversity of songs suggests multiple possible readings of the booklet; while it was clearly marked as a political text, it was made for entertainment and relieving boredom, as the introduction indicates. Furthermore, the difference in songs included and those that would have been deemed acceptable in the Japanese Empire collections suggests an ideological gap between the books’ creators, one produced through both physical and temporal distance. The book thus serves as a representation and testament to the complex political, ideological, and cultural landscapes produced through the upheaval and trauma of internment.

Further Reading:

Jane E. Dusselier. Artifacts of Loss: Crafting Survival in Japanese American Concentration Camps. Camden: Rutgers University Press, 2008.

Heather Fryer. “‘The Song of the Stitches’: Factionalism and Feminism at Tule Lake,” Signs Volume 35, Issue 3, 2010, pp. 673-698.

Brian Hayashi. Democratizing the Enemy: the Japanese American Internment. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Masanori Tsujita 辻田真佐憲. Nihon no gunka: Kokumin teki ongaku no rekishi 日本の軍歌 国民的音楽の歴史 [Japanese Military Songs: A History of National Citizen Music]. Tokyo: Gentōsha, 2014.

Posted by Patrick Carland

[1] Jane E. Dusselier. Artifacts of Loss: Crafting Survival in Japanese American Concentration Camps. (Camden: Rutgers University Press, 2008) 33-4.

[2] Brian Hayashi. Democratizing the Enemy: the Japanese American Internment. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004): 156.

[3] Artifacts of Loss, 1.

[4] Ibid., 7,

[5] Heather Fryer. “‘The Song of the Stitches’: Factionalism and Feminism at Tule Lake,” in Signs Volume 35, Issue 3, 2010, pp. 673-698: 677.

[6] Ibid., 679.

[7] Ibid., 681-2.

[8] Kokuminka: Aikoku shinkō kyoku (Citizen’s Songs: The Patriotic March) Nihon no Gunka http://gunka.sakura.ne.jp/nihon/aikoku.htm accessed May 1, 2020.

[9] Koga merodei kiki kurabe 12: Dare ka kōkyo wo omawazaru [Comparing old melodies: Dare ka kōkyo wo omawazaru] Tenisu to ran to dijikamera [Tennis, running, and digital camera] Blog post, March 3, 2010 https://blog.goo.ne.jp/mr_asuka/e/681bfe28f1e849421cb7b0beb707c050