Katsukawa Shun’ei 勝川春英 (1762-1819), Utagawa Toyokuni 歌川豊国 (1769-1825)

Shikitei Sanba 式亭 三馬 (1776-1822), author

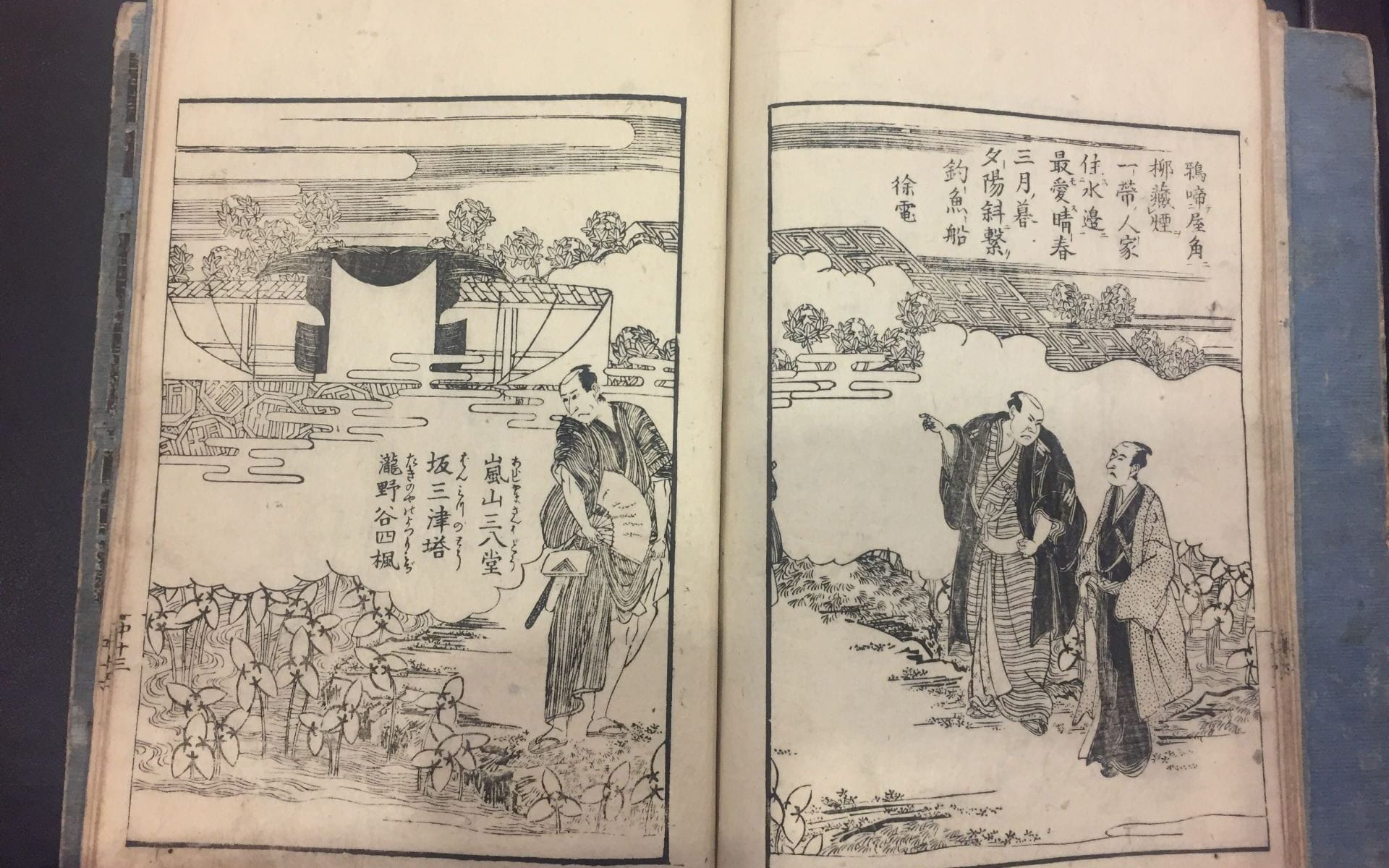

Shibai kinmō zui 戯場訓蒙図彙

Volumes 5-6 (of 8), 2 volumes bound as one

Edo period (1603-1868), 1803

Woodblock printed book; ink on paper

23.9 x 16.1 cm

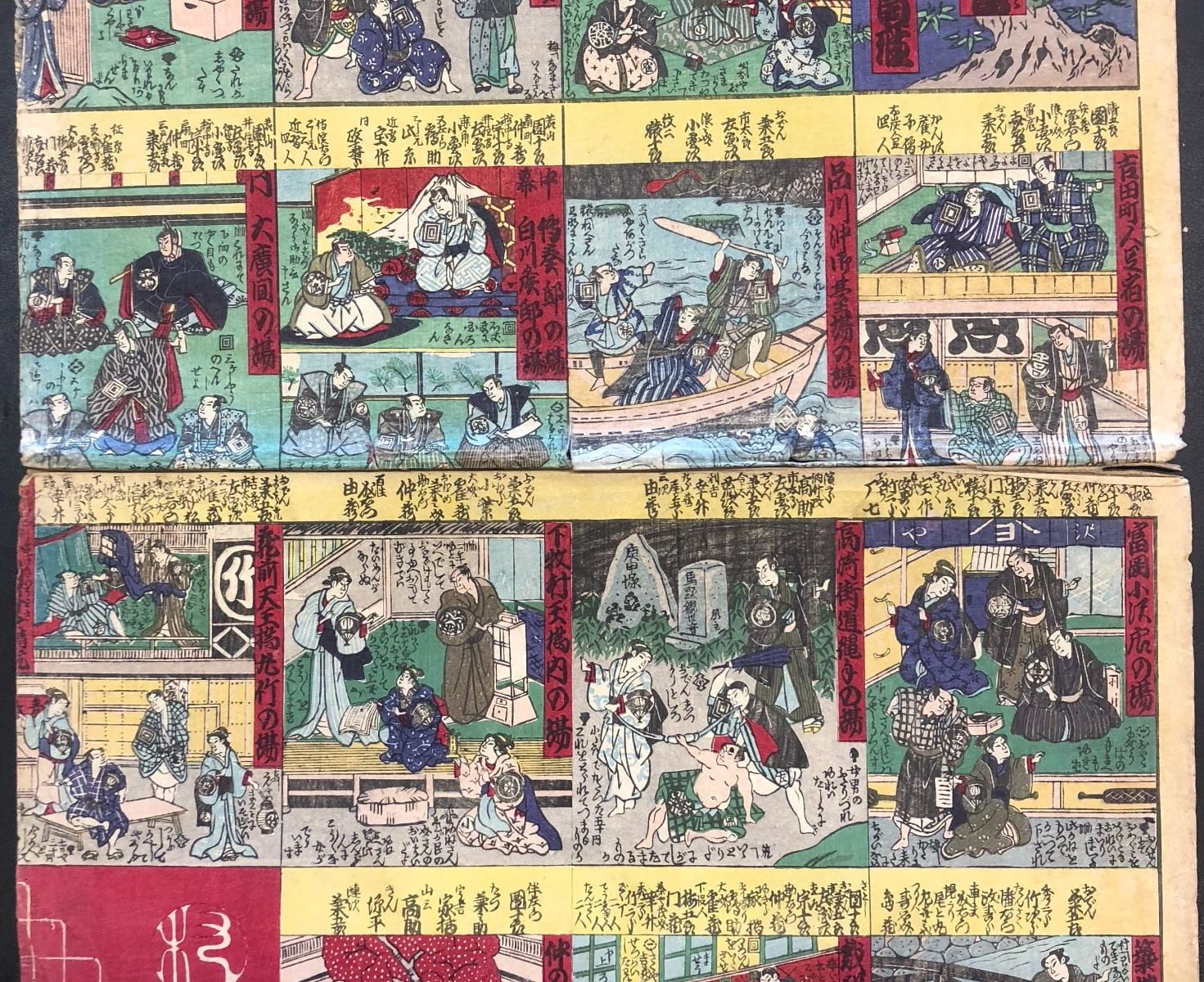

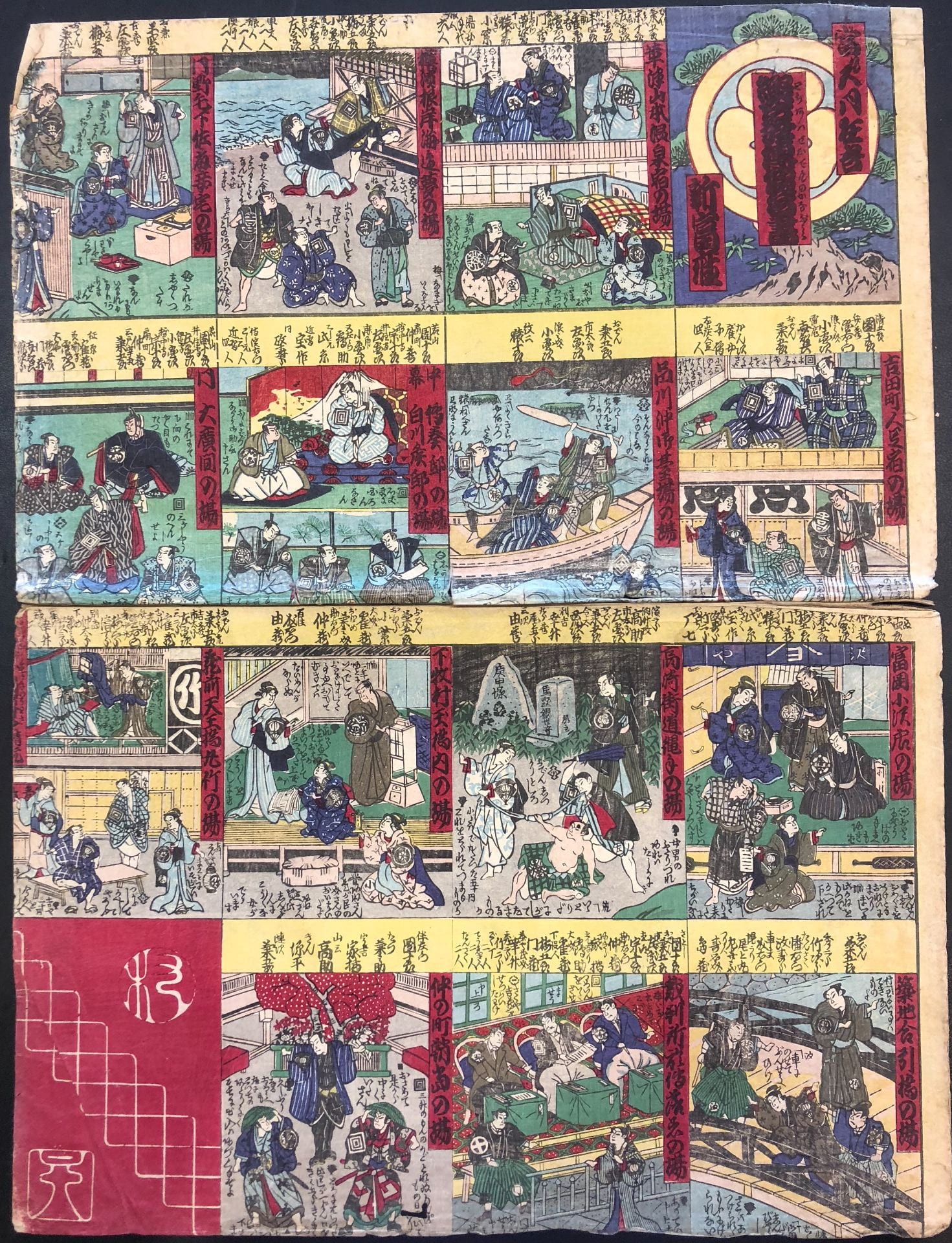

A comprehensive guide to the backstage world of Edo theater, Shibai kinmō zui attests to the significant role kabuki played in the popular culture as both an independent art form and a stimulus for literary production. Such books about the theater (and especially kabuki)—which modern scholars have broadly labeled as gekisho—take a remarkable variety of forms, from seasonal playbills to annual actor critiques.

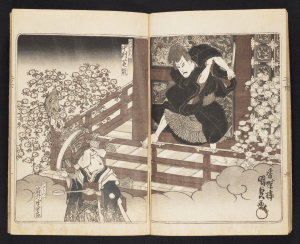

An illustrated encyclopedia of the theater, Shibai kinmō zui would have granted readers access to the backstage life of kabuki in book form, its pages replete with images and accounts of the hidden mechanisms through which plays were brought to life. Novel illustrations of stage effects, actors backstage studying their lines, and depictions of props are but a few examples. In the opening shown, Shun’ei and Toyokuni present a range of disembodied hair and beard styles. At the bottom center of the right page, they depict the towering hairstyle to accompany a fearsome hannya mask, used to represent a female demon. On the left page, the prim and proper styles of a variety of female characters are juxtaposed with the hairstyle of an old woman at the bottom right.

Kikuchi Hisanori, best known by his pen name Shikitei Sanba, is regarded as one of the great writers of kokkeibon, a variant of comedic literature that emerged during the mid to late Edo period. Sanba employed a tongue-in-cheek parody of the conventional encyclopedia to detail everything about kabuki theater. As comprehensive as it is humorous, this novel marriage of form and content also utilized the cultural capital of two eminent artists in the realm of kabuki: Katsukawa Shun’ei and Utagawa Toyokuni. At once a parody, an encyclopedia, and a guidebook to the backstage world of kabuki, Shibai kinmō zui exemplifies how permeable the boundaries between different cultural forms and traditions were in early modern Japan.

Francesca A. Bolfo

Selected Readings:

Akama, Ryō. Zusetsu Edo no engekisho: Kkabuki hen. Tokyo: Yagi Shoten, 2003.

Gondō, Yoshikazu, Takeshi Moriya, and Isoo Munemasa, eds. Kabuki, Nihon shomin bunka shiryō shūsei. Vol. 6. Tokyo: San’ichi Shobō, 1973.

Leutner, Robert. Shikitei Sanba and the Comic Tradition in Edo Fiction. Harvard-Yenchingld Institute Monograph Series 25. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985.