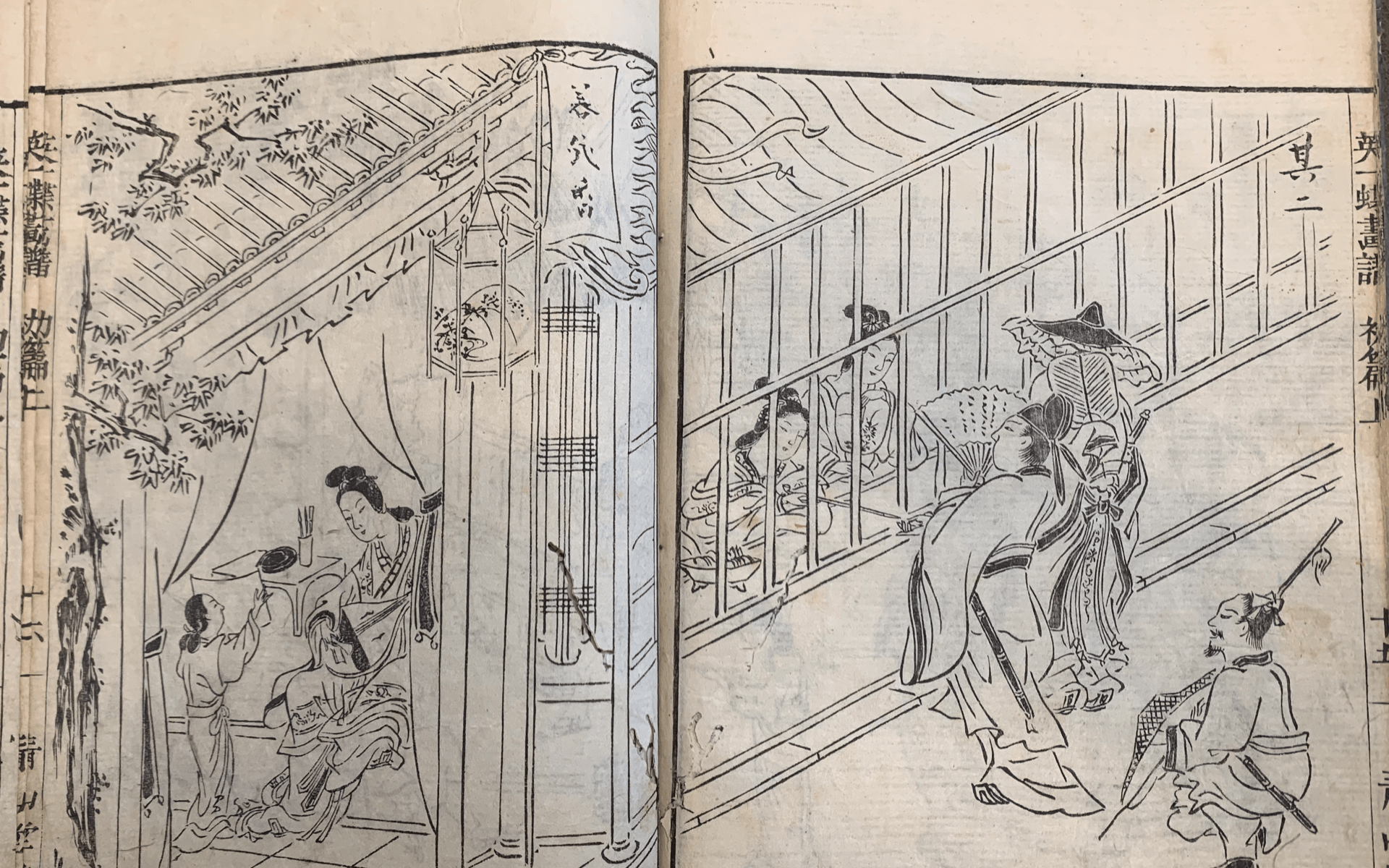

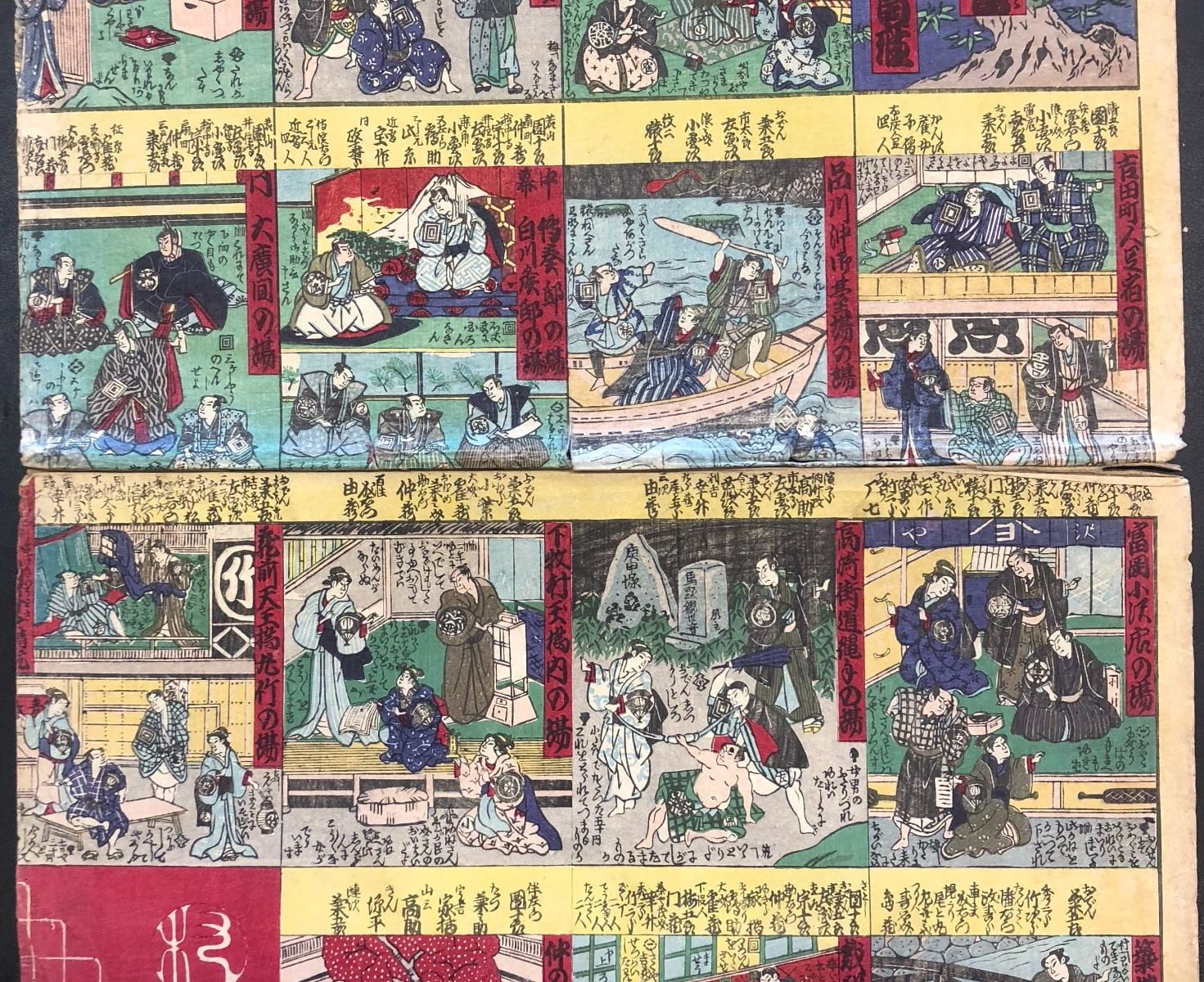

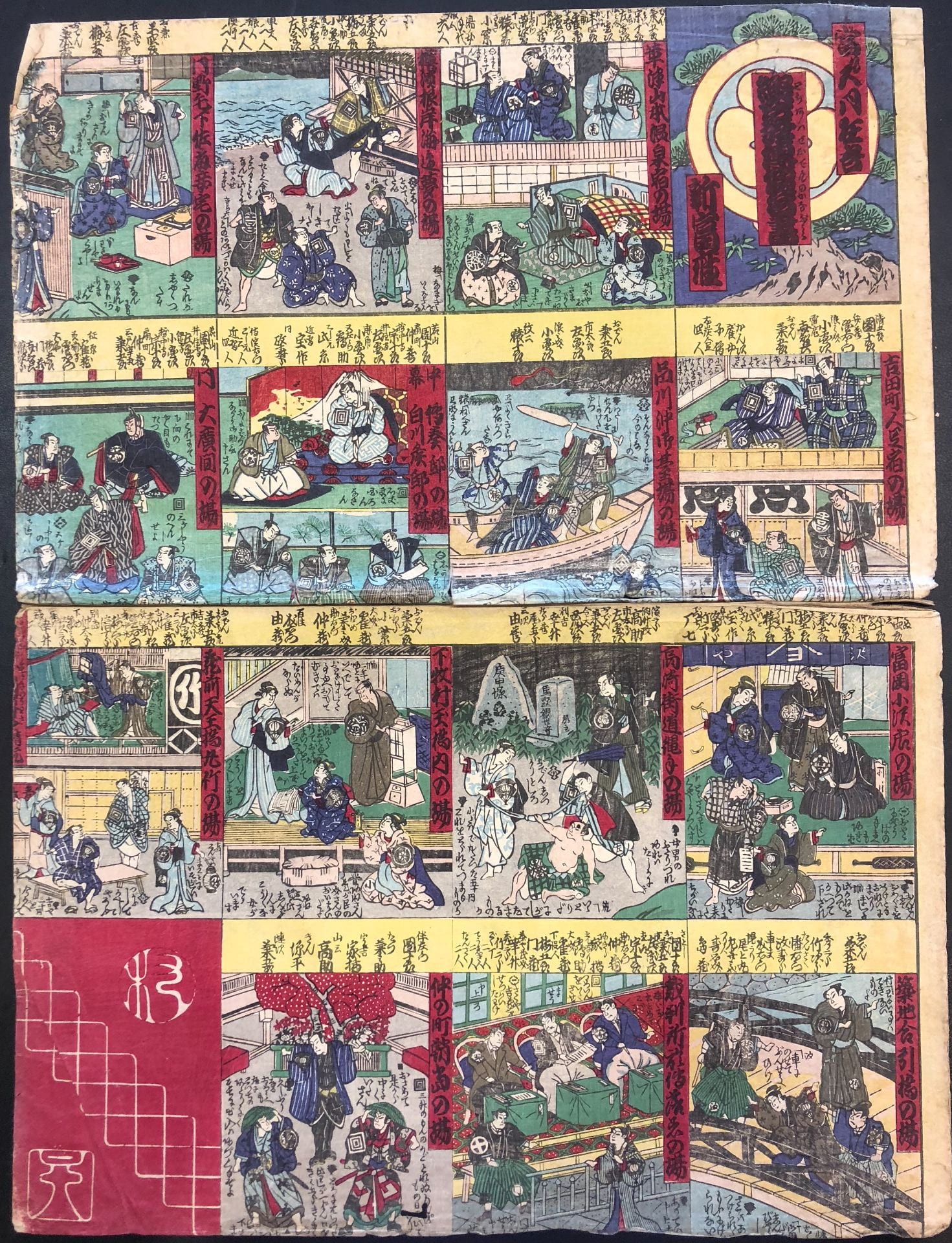

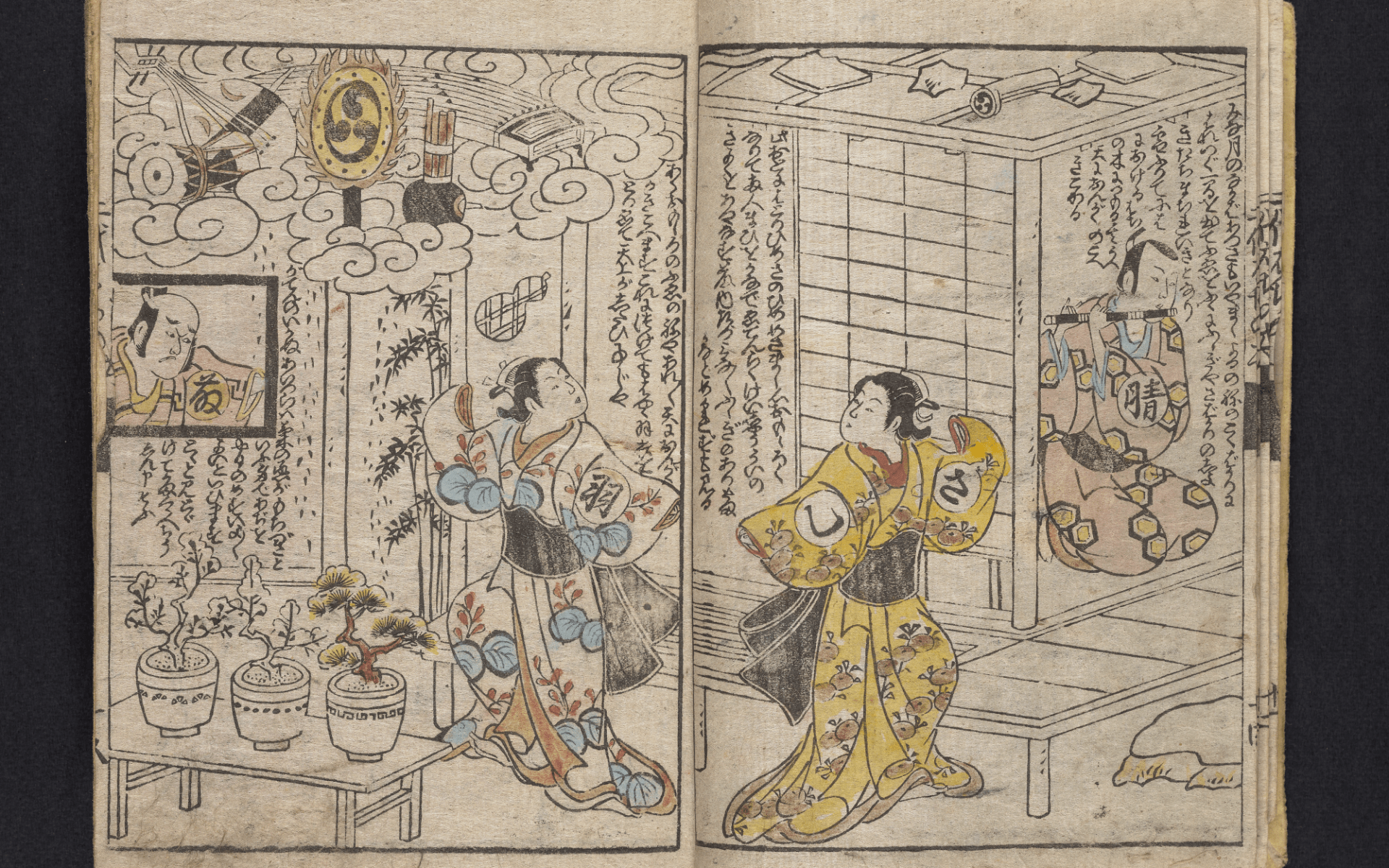

Artist: Suzuki Rinshō 鈴木隣松 (-1803) after Hanabusa Itchō 英一蝶 (1652-1724)

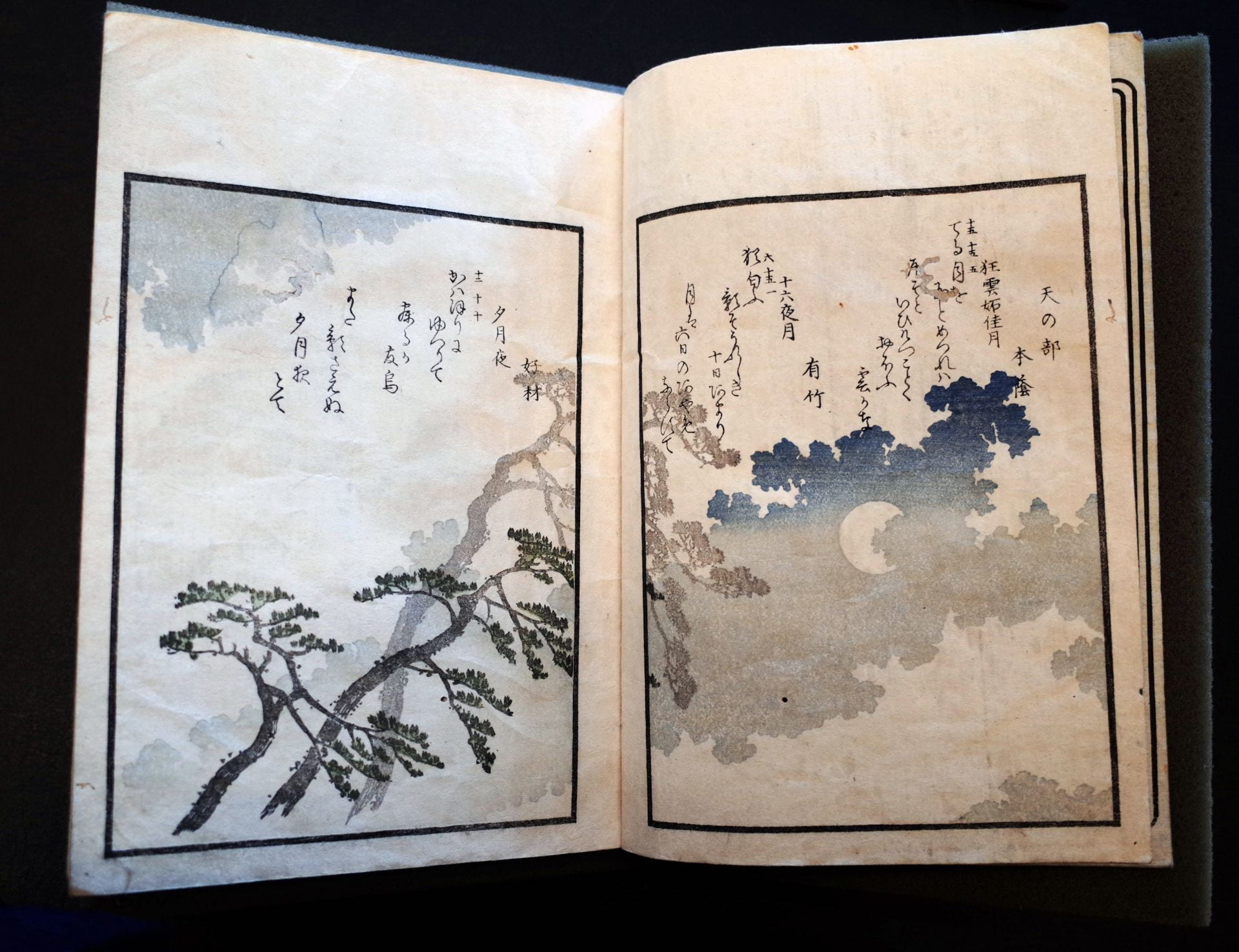

Title: Itchō gafu 一蝶画譜 (Itchō Painting Album)

Alternative Title: Hanabusa Itchō gafu 英一蝶画譜 (Hanabusa Itchō Painting Album)

Date: First month, 1770

Description: 3 volumes

Medium: Woodblock printed; ink on paper; some color in volume 1; paper covers

Dimensions: 8.2cm x 27.0 cm (volume 1 and 2); 8.0 cm x 25.0 cm (volume 3)

Publisher: [Nishimura Sōshichi]

Collector’s Seal: ?sai, ?斎on volume 3

Provenance: Margaret “Peg” Palmer

Gift of Mr. Arthur Tress

Object Number: Volume 1 and 2, Box 16 Item 7

https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977502570303681;

Volume 3, Box 8 Item 18

https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977502575003681

This book features a wide range of themes from Hanabusa Itchō’s (1613–1685) painting oeuvre what is in effect a printed painting album. Many of the paintings are based on Sino-Japanese subjects which were often made by the artists in the Kano studio. These images demonstrate Itchō’s ability to convert traditional subjects into expressive, humorous, and relevant images, many featuring his observations from urban life.

The first image shown here depicts a man visiting the pleasure district. The man, his servant, and the sex workers are dressed in Tang-dynasty costumes. Meanwhile, the window lattices are in the style of Edo-period pleasure districts. Itchō himself was reportedly a visitor to the Yoshiwara, the pleasure district in Edo.

The second image included here is called the Asazuma Boat, after one of Itchō’s most famous paintings. This picture shows a woman waiting to meet her guest on a boat near Asazuma after the fall of the Heike. Suzuki Rinshō seems to have tried to represent the large variation of brushstrokes often featured in Itchō’s paintings. In the preface, Rinshō described these images as giga, playful paintings.

Hanabusa Itchō is known for his use of humor to illustrate the urban experience of commoners in the city of Edo. At a young age, he apprenticed in the studio of Kano Yasunobu in Edo, doing so by order of his local daimyo. He wrote haikai poems and was active in the circle of Matsuo Bashō (1644-1694). In 1698 he was banished to the island of Miyake by the shōgun for eleven years and made his living by selling paintings there. He adopted the name Hanabusa Itchō and continued his artistic practice after he returned to Edo. After Itchō’s death, his student Hanabusa Ippō (1691-1760) published painting albums in the style of Itcho (see Ippō, Ehon zuhen (1752, Tress Collection Box 39, Item 11) and Eihitsu hyakuga (1758). Suzuki Rinshō, a samurai who relinquished his position and studied painting, publishing this and other albums featuring Itchō’s paintings after Ippō’s death.

Other copies of this book are in the British Museum, Harvard Art Museums, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and New York Public Library

Selected Reading

Hillier, Jack. 1987. The art of the Japanese book. London: Wilson for Sotheby’s Publications. 216-221

Wattles, Miriam. The Life and Afterlives of Hanabusa Itchō, Artist-Rebel of Edo. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

Posted by Tim Zhang