Artist: Kawamura Kihō 河村琦鳳 (1778-1852)

Title: Kihō’s Picture Album

Date: after 1826 (Bunsei 9)

Medium: Woodblock printed; ink and color on paper

Dimension: 25.9 x 17.8 x 1.1 cm

Publisher: Yoshida Shinbē 吉田新兵衛 (Bunchōdō 文徴堂)

Arthur Tress Collection, Box 8, Item 15

See digital images

https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977502575803681#franklin-availability

Artist: Kawamura Kihō 河村琦鳳 (1778-1852)

Title: Kihō’s Picture Album

Date: 1827 (Bunsei 10)

Medium: Woodblock printed; ink and color on paper

Dimension: 25.9 x 17.8 x 1.1 cm

Publisher: Yoshida Shinbē 吉田新兵衛 (Bunchōdō 文徴堂)

Arthur Tress Collection, Box 8, Item 7

https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977502569003681#franklin-availability

Artist: Kawamura Kihō河村琦鳳 (1778-1852)

Title: Kihō’s Picture Album

Date: after 1826 (Bunsei 9)

Medium: Woodblock printed; ink and color on paper

Dimension: 25.9 x 17.8 x 1.1 cm

Publisher: Yoshida Shinbē 吉田新兵衛 (Bunchōdō 文徴堂)

Arthur Tress Collection, Box 28, Item 22

https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977502739203681#franklin-availability

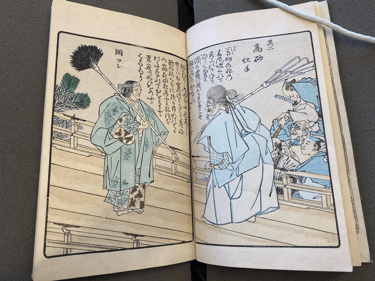

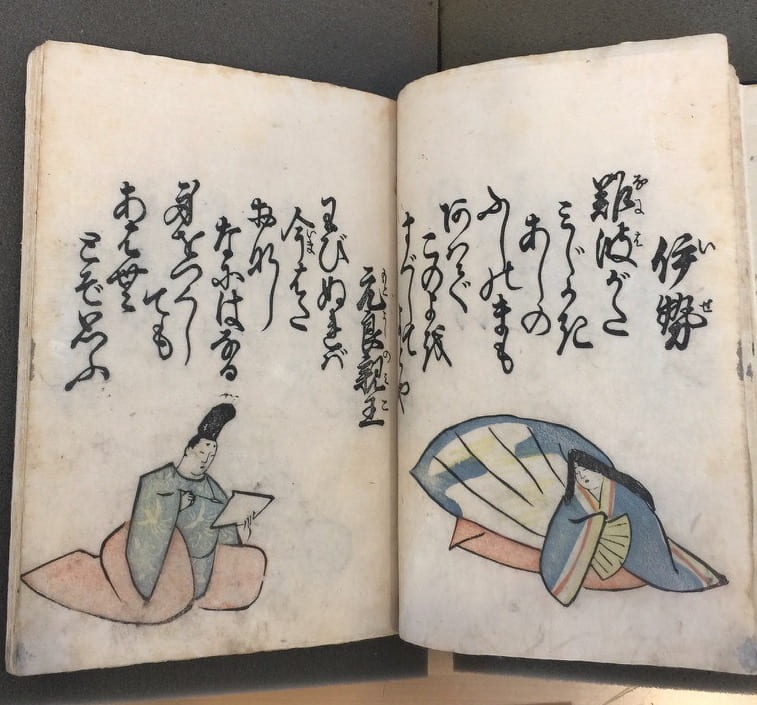

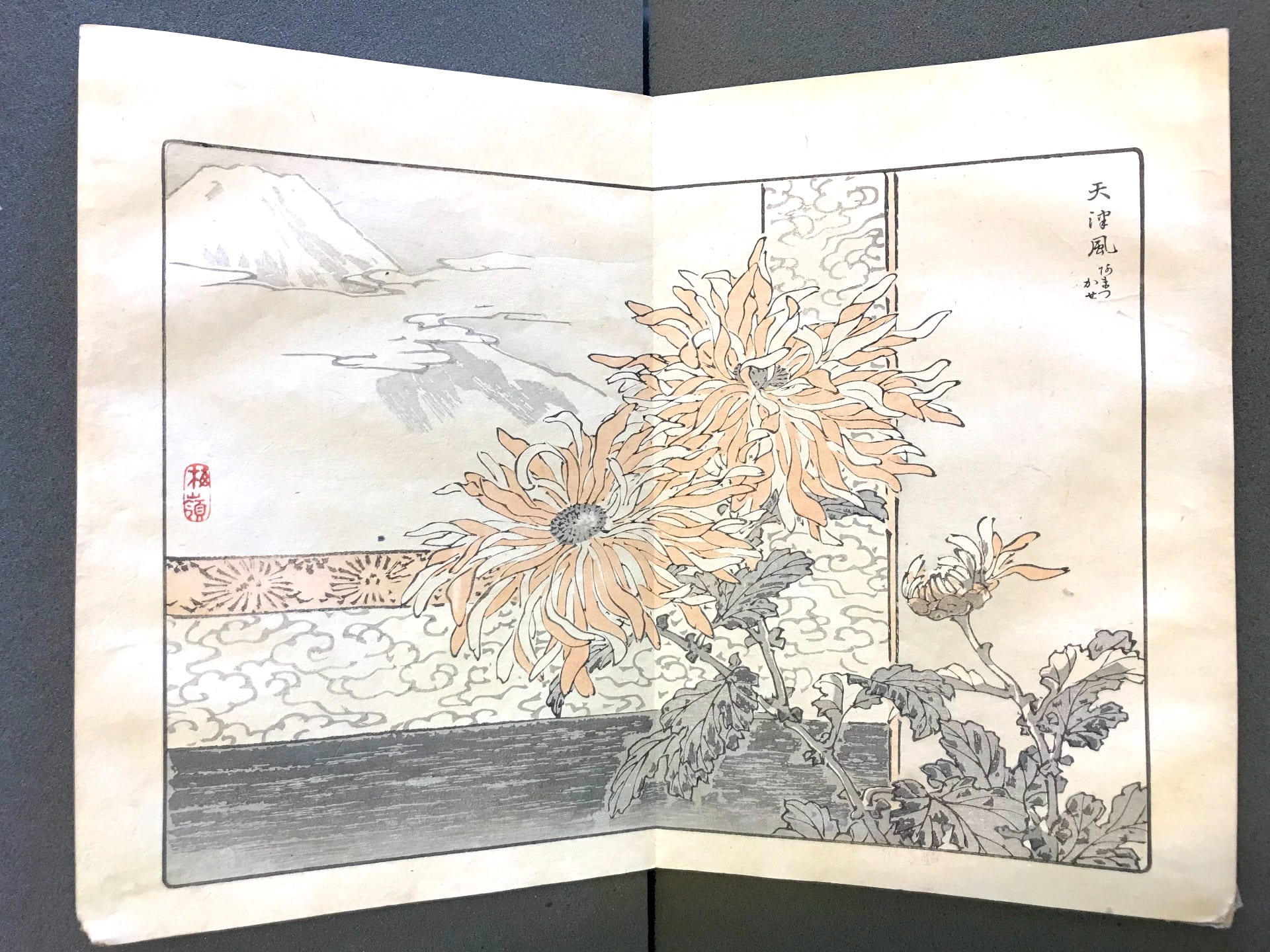

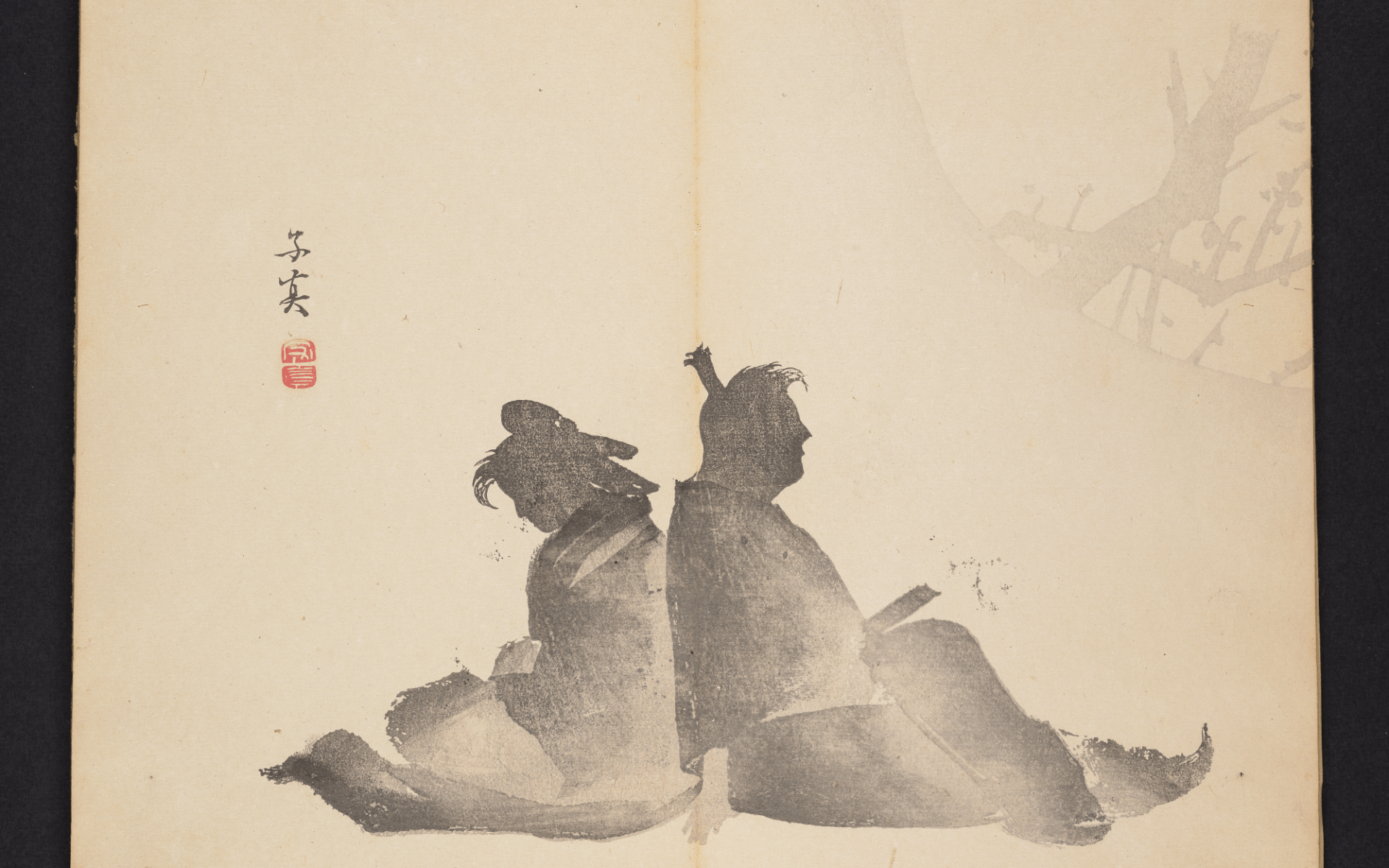

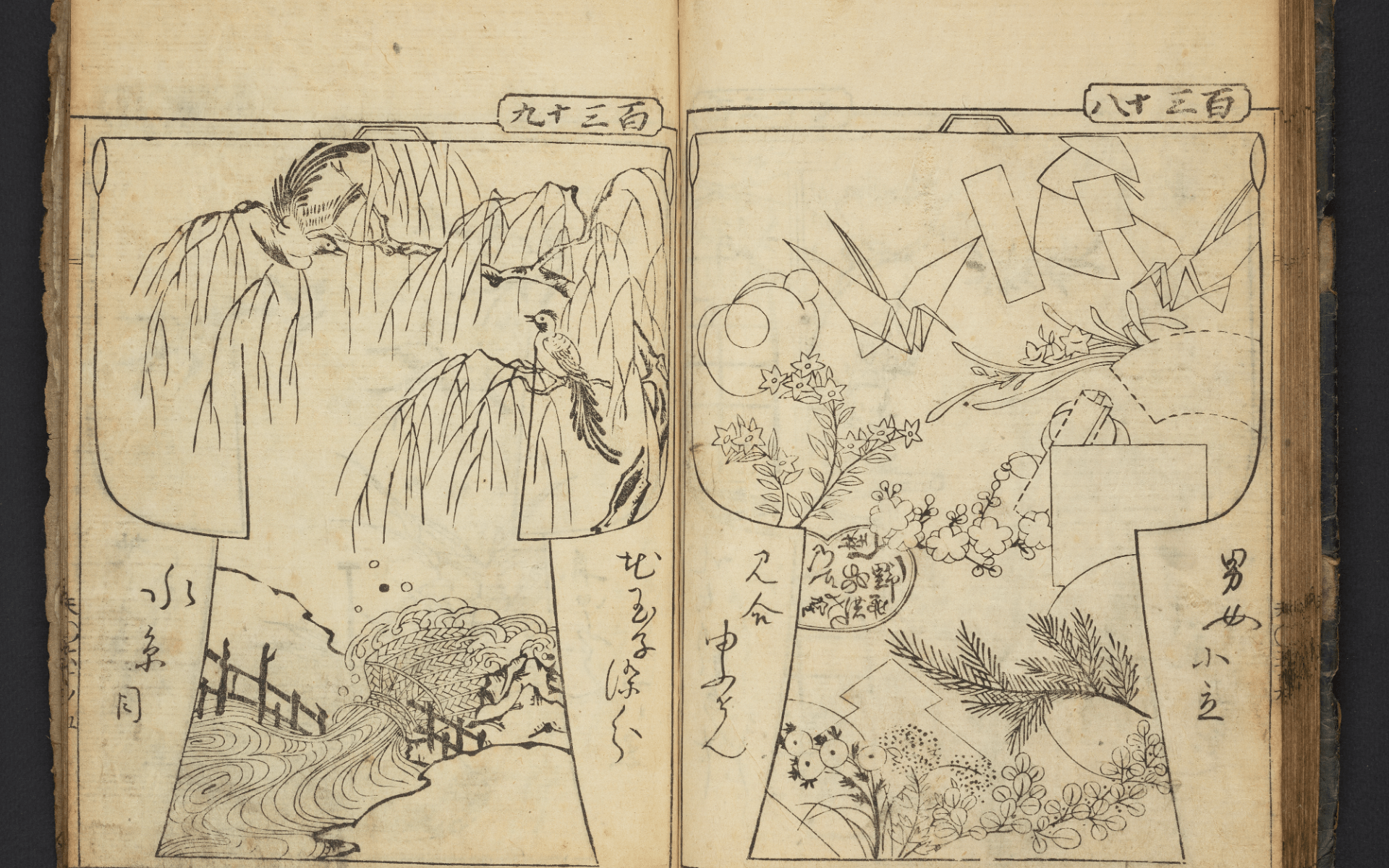

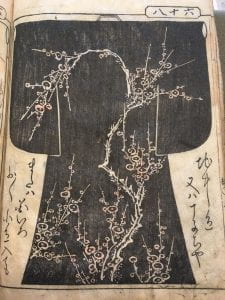

Kihō gafu, a picture album by Kawamura Kihō, contains 30 double-page illustrations of flowers, animals, rural landscapes, and human figures in everyday life scenes. Human figures are shown enjoying bucolic tranquility and revealing a free spirit. Subjects are depicted with ink lines in a calligraphic manner and embellished with lucid pale colors, evoking a Chinese painting style. In some illustrations, the artist abandoned the color-filling technique but applied colors directly to define the shape of the subjects, offering a painterly effect. Kihō gafu also features many inventive compositions, in which the single sheets not only stand as independent scenes but also can be unified as compelling double-page illustrations. In one opening, for example, a bough ascends from the right bottom corner in a diagonal way and traverses the central division into the opposite sheet, in which a little bird is shown hanging itself down from a branch and pecking the red fruits (fig. 1). The bough, rendered with powerful brushwork, is printed so skillfully that it looks like an ink painting, and the little bird is depicted in a delicate manner, balancing the boldness of the bough as well as its visual weight.

Kyoto-based artist Kawamura Kihō was the adopted son of Kawamura Bunpō. Kihō followed in the style of his teacher, Bunpō, adopting his distinctive approach to Chinese literati painting. Many of Kihō’s illustrations thus echo Bunpō’s designs. Kihō gafu was published by Yoshida Shinbē from his shop, the Bunchōdō文徴堂, located in Kyoto. The three titles in the Tress collection include different dates in the prefaces, postscripts, and colophons, demonstrating that these titles were produced over several years. For example, in book 8.7, the preface includes a date of Bunsei 7 (1824), the postscript is dated Bunsei 9 (1826), and the colophon to Bunsei 10 (1827); thus, the earliest date we can give to this printing is 1827. The publication dates of the other two impressions in the collection are unknown, as they do not have colophon dates, but they cannot precede Bunsei 9 (1826) given the date of the postscript included in both impressions. The three impressions of Kihō gafu also display different color and shade patterns, signifying an alteration of color woodblocks in the course of reprinting. In comparison with other two copies, the impression 8.7 seems to have a more romanticized and naturalized palette, including a green color with a warmer tone, the skin color with a lighter orange hue, and the addition of rose pink. Further research will need to be conducted to understand more about what the differences in color and hue might indicate between these three impressions.

Other Impressions

The Gerhard Pulverer Collection, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington D.C

Smithsonian Libraries, Washington D.C

The Metropolitan Museum, New York, NY

The New York Public Library, New York, NY

The British Museum, London

Selected Reading

Hiller, Jack. Introduction to Japanese Prints: 300 Years of Albums and Books. London: British Museum Publications Ltd., 1980.

Tinios, Ellis. “Kawamura Bumpō: The Artist and his Books.” Print Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 3 (1994): 256-91.

Posted by Aria Diao

Nov. 14, 2019