current research directions

cell biology of meiotic drive: genetic cheating in violation of Mendel’s First Law

Every high school biology student learns about the 3:1 phenotype ratio observed by Mendel in his monohybrid crosses of pea plants. Underlying this observation, and at the core of Mendelian genetics, is the concept that gametes are equally likely to carry either allele of a gene. Selfish genetic elements can cheat by violating this principle to increase their representation in the gametes (and therefore in the progeny) by meiotic drive. Examples from a range of eukaryotes show that meiotic drive is a widespread phenomenon that impacts many aspects of reproduction, genetics, and evolution. These violations of Mendel’s First Law should perhaps not surprise us because the opportunity to cheat is inherent in the haploid-diploid life cycle that underlies sexual reproduction in all eukaryotes, with genetic elements competing for transmission to the offspring through meiosis, the process by which haploids are generated. Female meiosis provides the most straightforward way to cheat because only one egg is produced from two rounds of cell division, so selfish elements compete for transmission to the egg. Our studies focus on the cell biology of female meiotic drive, using mouse model systems in which we can directly observe drive and ask mechanistic questions. The significance of meiotic drive for genetics and evolutionary and reproductive biology makes the cell biological questions particularly exciting. Furthermore, understanding how selfish centromeres cheat the meiotic segregation machinery will provide new insights into centromere biology and meiotic cell division. See our papers in this area …

|

Meiotic spindle asymmetry. Signals from the polarized cell cortex (green) in mouse oocytes regulate microtubule tyrosination (white) to generate spindle asymmetry in meiosis I. This asymmetry can be exploited by selfish centromeres to bias their transmission to the egg. See Akera et al. 2017. |

Functional consequences of natural variation in repetitive DNA

Satellite DNA is composed of tandemly repeated DNA sequences that make up large non-coding regions of eukaryotic genomes (e.g. 7% of the human genome) and are among the most rapidly evolving genomic sequences. Recent advances in long-read sequencing technology have made incredible progress in characterizing the genetic composition and diversity of repetitive satellite arrays, but functional consequences of this diversity remain largely unknown. We have developed mouse model systems, taking advantage of natural variation between strains and divergence between closely related species, to study consequences of variation in repetitive DNA. Our studies show that satellite variation impacts fundamental cell biological processes in female meiosis (chromosome segregation, pericentromere chromatin packaging) and in the early embryo (formation and function of centromere chromatin and pericentromere heterochromatin, telomere length regulation). See our papers in this area…

Maintaining chromosomes in the mammalian germline

The extended prophase I arrest (lasting months to decades) in mammalian oocytes raises questions about how chromosome cohesion and centromere identity are maintained. Cohesin proteins and CENP-A nucleosomes, which define the centromere, assemble onto chromosomes before the prophase arrest and must persist through the arrest. Using mouse oocytes as our experimental system, we showed gradual loss of cohesin proteins from chromosomes during prophase I, reduced cohesion function, and age-related chromosome segregation errors consistent with cohesion defects. Our findings established a mechanistic basis for the well-known increase in aneuploidy associated with advanced maternal age. In contrast, we showed that CENP-A nucleosomes are stable for the fertile lifespan of the female (>1 yr) in the absence of any new assembly. This remarkable stability underlies centromere inheritance through the female germline. After fertilization, we showed that new centromere chromatin assembly depends on centromere DNA sequences and on the maternal Cenpa genotype in addition to the established epigenetic pathway. See our papers in this area …

|

CENP-A staining in a mouse oocyte at metaphase I. CENP-A persists at centromeres for >1 year after the gene has been deleted in the oocyte, demonstrating the remarkable stability of centromeric nucleosomes.

See Smoak et al. 2016. |

chemical optogenetic tools to manipulate living cells

Tools for manipulating protein levels at intracellular structures, with temporal and spatial control, will enable the next generation of experiments to dissect dynamic systems in cell biology. Kinetochores are a prime example: multi-subunit complexes whose function depends on dynamic changes in localization of kinases, MT-associated proteins, and checkpoint signaling proteins throughout cell division. We developed optogenetic probes, in collaboration with the Chenoweth Lab, based on photo-caged or photo-cleavable chemical dimerizers. These probes allow us to recruit proteins to individual kinetochores or other intracellular structures with light, with both spatial and temporal precision. We have applied these tools to manipulate checkpoint signaling, molecular motors, and Aurora kinase activity at kinetochores. See our papers in this area …

Mitotic and meiotic chromosome segregation

We use innovative tools and model systems for mechanistic cell biological studies of mitosis and meiosis. For example, we developed FRET-based biosensors to track changes in Aurora B kinase activity in living cells with high temporal and spatial resolution, leading to a widely cited model for how spatially regulated Aurora B kinase activity regulates kinetochore-microtubule interactions. We also established a mechanism for phosphatase recruitment to kinetochores to oppose Aurora B and showed that Polo-like kinase-1 (Plk1) stabilizes kinetochore MTs in opposition to Aurora B. For studies of meiosis, we developed hybrid mouse model systems, taking advantage of karyotype variation, to show spatial regulation of attachments by Aurora A at spindle poles, complementary to tension-dependent regulation by Aurora B at centromeres. Most recently, we used a chemical optogenetic approach to manipulate Aurora B at individual kinetochores and showed that the response to kinase activity depends on centromere tension to induce distinct error correction mechanisms. We used similar approaches to challenge the textbook model for anaphase chromosome segregation by manipulating specific microtubule populations within the spindle See our papers in this area …

|

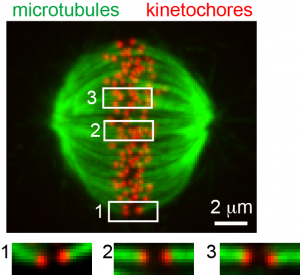

Kinetochore microtubule bi-orientation. A metaphase cell stained for microtubules (green) and kinetochores (red). The image is a maximal intensity projection of a confocal z-series. Insets are optical sections showing bi-oriented sister kinetochore pairs.

From Liu et al. 2012. |

collaborators

Ben Black, Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics

Dennis Discher, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

Dave Chenoweth, Department of Chemistry

Roger Greenberg, Department of Cancer Biology

Andrew Modzelewski, School of Veterinary Medicine

Mia Levine, Department of Biology

Iain Cheeseman, Whitehead Institute and MIT

Alexey Khodjakov, Wadsworth Center

research support (past and present)

National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS)

National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI)

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD)

National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Searle Scholars Award

Discovering the Future Research Grant, University of Pennsylvania

Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania

Physical Sciences Oncology Center at Penn (PSOC)

Penn Center for Genome Integrity

Penn Center for Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases

Emerson Collective Cancer Research Fund

Nano/Bio Interface Center, University of Pennsylvania

University Research Foundation, University of Pennsylvania

Institute on Aging, University of Pennsylvania

Penn Genome Frontiers Institute

Translational Biomedical Imaging Center, Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, University of Pennsylvania

Penn Center for Study of Epigenetics in Reproduction