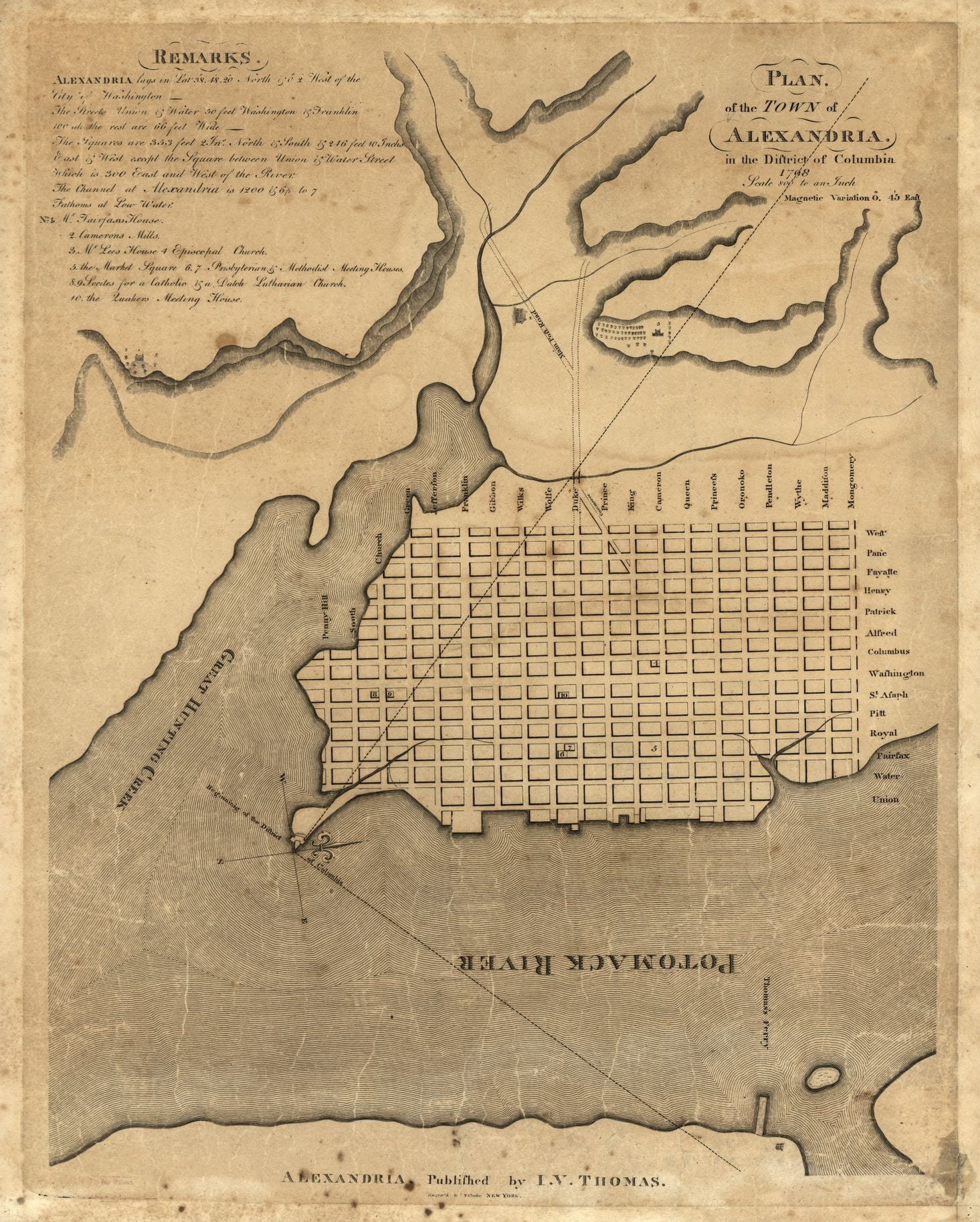

It was an August day in 1768 that the young Scotsman Alexander “Sandie” Wilson was told he would be traveling to Virginia. He had been outside with friends when he was called into his Glasgow home, sat down, and informed of the situation. “Well Sandie,” his father told him, “you must go over seas.” Several months earlier, while discussing his future, Sandie had told his father that he “wou’d like better to go abroad than stay at home.” Now everything had been arranged. Sandie would be sent to Alexandria, Virginia to work at a tobacco store as an assistant. Soon he would be in the Chesapeake, selling goods, managing account books, and buying tobacco.1

I first encountered Sandie Wilson’s letterbooks several days into a 2015 research trip to Glasgow’s Mitchell Library. Based on their catalogue description of this collection, I was not expecting much. I was researching for my essay on bookselling and the tobacco economy in the colonial Chesapeake and had come to Scotland to explore the financial records of the city’s major tobacco firms. I figured Wilson’s letters, even if they did not contain much of use, would provide a brief respite from the scrawled accounts written in the ledgers, daybooks, and inventories I had been poring over. What I did not expect was how integral Wilson and his highly descriptive letters would become to my work and how these texts would force me to think more deeply about how to use different kinds of sources.

I had requested Wilson’s letterbooks, which include material from 1768 to 1786, knowing that he was one of many young men who left Scotland for Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina during the eighteenth century. Like others, Wilson found work for a Glasgow merchant firm, Glassford and Henderson, that sent him to the colonies to work in a store whose primary focus was on the tobacco trade. Yet, these stores functioned, as Ann Smart Martin has described, as “true emporiums,” selling “everything from nails to novels.” The storekeepers who operated them liberally extended credit to planters, allowing colonists to purchase a variety of imported goods, and they collected tobacco in settlement of accrued debts.2

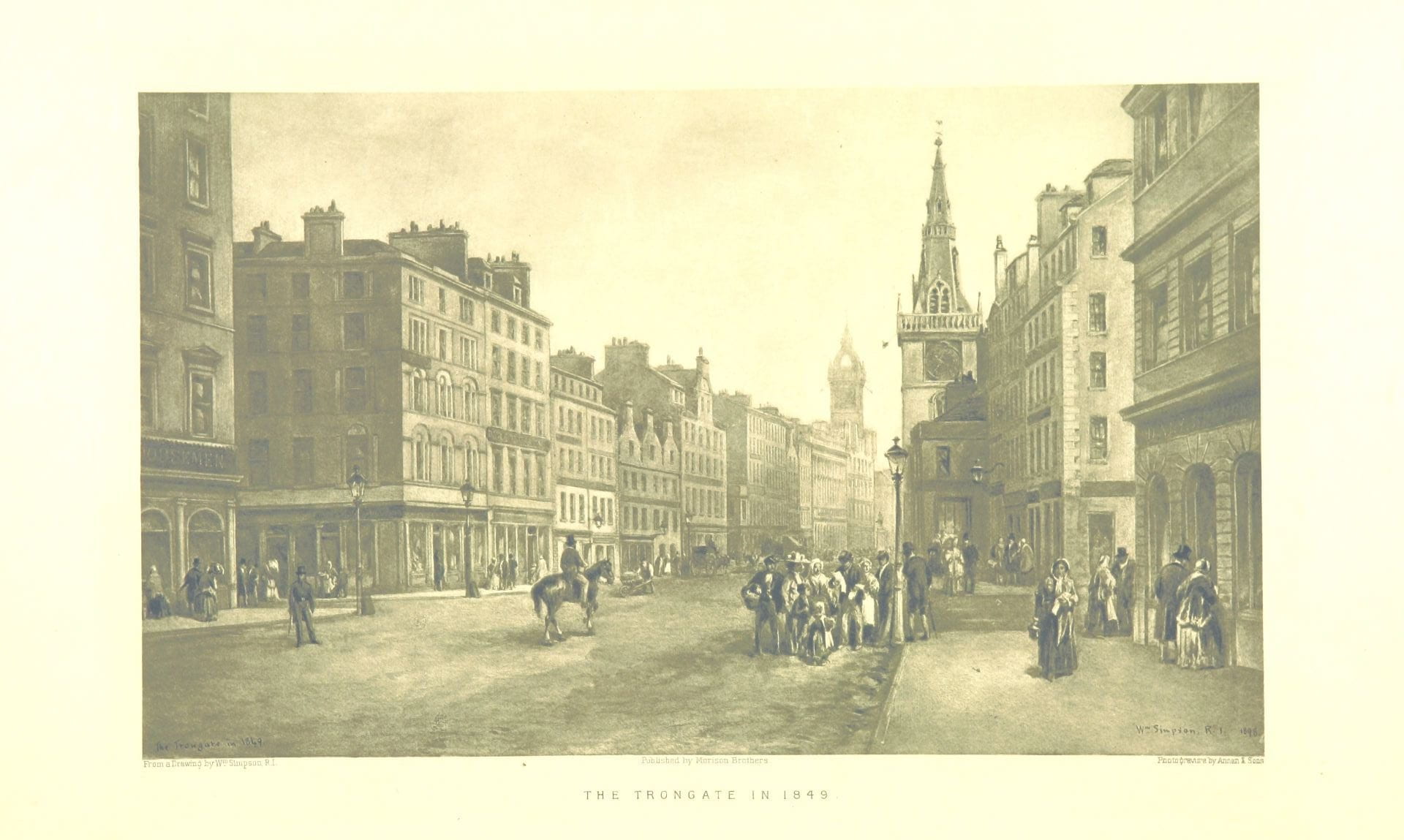

I quickly realized that Wilson’s letters gave me an insider’s account of this trade. Writing to his parents in 1769, he described a typical day. From waking until late in the evening, Wilson was “constantly in the store.” Each morning he had to “put every thing to rights” before waiting on “planters…all day long.” Even after locking up around sunset, his work was not done, as he then spent time “copying accounts” and “posting up the days transactions.” As I continued reading, Wilson’s letters continued to yield surprises. Due to a health crisis, he returned to Glasgow in 1771, but soon became involved in the trade again, this time as a bookseller. With a partner, Alexander Dunlop, he set up a shop on the city’s Trongate street and began to sell books, as he put it, in the “export way.” Dunlop and Wilson sold books to merchant firms like Glassford and Henderson that then shipped them to the stores the firm operated in Virginia and Maryland. Here, in Wilson’s letters, were not only details about the workings of a store in the Chesapeake, but also evidence of the way an Atlantic trade in books fit within the tobacco economy.3

While I had expected to spend only a morning researching in the letterbooks, my work soon stretched to a day and then to much of a week, and I was often surprised by what I found. The bulk of Wilson’s letters, I discovered, were not about business or his time in Virginia. Rather, he wrote most often to several women with whom he had struck up romantic, or at least, flirtatious relationships. These were fun to read, full as they were of gossip, epistolary romance, and real emotion. Wilson estimated that he exchanged over a thousand pages of letters with these women.4 As I read, I followed how Sandie’s affections moved from Flora to Margarette to Sinnie. He was very much a romantic, and his correspondence was highly florid and sentimental prose. In a letter to Flora, he apologized for this tendency, and for his logorrhea more generally:

I beg your excuse for making you read so much nonsense, could I’ve penn’d the rabble of words I’ve shuffled together in the manner [of] a Rousseau, Fielding or Voltaire [I] wou’d have done, that ‘twou’d have been worth my sisters reading, but alas…well I’ve done my best & know my little highland lassie will forgive me.5

Ultimately, Sandie’s letter books paint him as unlucky in love. His correspondence with these women always began with high hopes that this love would be lasting, but then slowly became less intimate, and, eventually, petered out. Both Flora and Margaretta were married by the early 1780s and Sinnie died, apparently of tuberculosis, in October 1784. Wilson blackened two facing pages to mark the event in his letter book, and wrote poetry to commemorate her. Soon thereafter, all of Sandie’s correspondence slowed, and in 1786, after his father died, it stopped altogether.6

The abrupt conclusion to these letters left me with questions. What became of Sandie? Did he ever marry and have a family? Was he successful in business? I found answers not in an additional cache of letters, but an account book of his personal expenses that he kept from the 1780s to the early 1800s. Read chronologically the ledger tells a story of how this hopeless romantic finally found love (or, at least, a suitable marriage) and started a family.

In February 1787, he purchased marriage gloves as well as numerous items for one Christina Lawrie, a Scottish woman who became his wife. By 1789, Christina was evidently pregnant. In September of that year, he purchased “1 pair nursing stays for Christina,” and by October, he had paid five shillings to enter his “daughter Mary” into the kirk session books. The subsequent years’ expenses detail purchases of toys for Mary, visits to family, and even a trip to London. By 1803, when his private ledger ended, it seems that Wilson had found a happy life, one for which he had long searched.

While his letters provided context for the ledgers and account books of Scottish tobacco merchants, ironically, perhaps, it was his ledger that helped narrate, contextualize, and provide a hint of a happy ending for his own life.7 Together, the different types of evidence they provide are valuable entry points into the mental and material worlds of the past. They make it possible to step into someone like Sandie’s world and glimpse, briefly, his business ambitions and private hopes. In their own ways, these sources allow the historian to speak with the dead, providing tantalizing evidence of past lives filled with passion, verve, and curiosity.

Philip Mogen (he/him/his) is a Ph.D. candidate in the history department at the University of Pennsylvania. He studies print culture in the British Isles and British Atlantic.

Read Philip Mogen’s article, “The Scottish-Chesapeake Tobacco Trade and the Economics of Book Importation,” in the Winter 2022 issue of Early American Studies.- Glasgow City Archives, TD1/1070: Alexander Wilson Letterbook Vol. 1: Alexander Wilson to Flora McDonald, 11 March 1777. Wilson was the son of the typefounder and astronomer Alexander Wilson and brother to Patrick Wilson, also a typefounder and astronomer. ↩

- Ann Smart Martin, Buying into the World of Goods: Early Consumers in Backcountry Virginia (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 17. ↩

- Glasgow City Archives, TD1/1070: Alexander Wilson Letterbook Vol. 1: Alexander Wilson to his parents, 7 April 1769; Glasgow City Archives, TD1/1070: Alexander Wilson Letterbook Vol. 1: Alexander Wilson to his parents, 17 December 1769; Glasgow City Archives, TD1/1070: Alexander Wilson Letterbook Vol. 1: Alexander Wilson to Alexander Millar, 21 August 1772. ↩

- Glasgow City Archives, TD1/1072: Alexander Wilson Letterbook Vol. 3: Alexander Wilson to “Georgium,” 10 September 1786. ↩

- Glasgow City Archives, TD1/1070: Alexander Wilson Letterbook Vol. 1: Alexander Wilson to Flora McDonald, 11 March 1777. ↩

- Glasgow City Archives, TD1/1072: Alexander Wilson Letterbook Vol. 3: Blackened pages, 20 October 1784. ↩

- Glasgow City Archives, TD1/1073: Ledger of Alexander Wilson, household and personal expenses. ↩