Risk & Sharing: Inquiry by Video Game

A paper by Hillard Kaplan, Eric Schniter, Vernon Smith, and Bart Wilson was just published online at Proceedings of the Royal Society – B, and it’s really interesting. To pique your interest, I am going to start with a screenshot from the experiment.

In this study, students at ChapmanUniversity controlled avatars in a little video game-like environment, and could choose, in each of several rounds, whether to “hunt” or “forage.” Hunting meant choosing going to the left side of the screen, where there were high-variance high-payoff targets; foraging meant choosing going to the right side of the screen, where your payoff was essentially certain, but low. When you were done hunting or gathering, you could shoot your meat or potatoes from the storage bin in your heart – at least that’s what it looks like to me – to put it in your pot (i.e., consume it, which gave you points) or, importantly, to give it to another person’s avatar. Here, Yellow Avatar has put 12 units of food into her pot, which can hold a maximum of 18 units. Units are converted to cash at the end of the experiment. Avatars could chat with one another when they got sufficiently close to see one another’s chat bubbles, which appeared just beside the avatars’ head.

Kaplan et al. were interested in the explanation for why people share, especially, among hunter-gatherers, hunted food items. Their study was designed to distinguish between two different ideas. The first one is that sharing is insurance against risk. Because the hunt is not always successful, sharing buffers this risk. If I give you food when I’m successful but you are not, and vice versa, then we’re both better off. A second view is the “tolerated theft” view, which holds that “sharing” is really due to the fact that when I have hunted successfully, because of diminishing returns, it’s not worth it for me to defend my hunted items if you’re hungry and try to take it. Related, some have suggested that men hunt in order to signal their worth in order to gain benefits in the mating market.

As an empirical matter, hunted foods are shared a lot more than gathered foods. There is still debate about the reason for this. The authors write:

The goal of our virtual world laboratory experiment was to test the risk-reduction model of food sharing, under controlled conditions in which there was no scope for tolerated theft or gains from signaling quality.

Because they do not allow theft in the interface, if sharing of hunted items is observed, then they suggest that this works against the tolerated theft model. Their goal was to test a number of predictions, including (1) people who hunt – pursue the High Variance (HV) resource, in their game – would share more than people who forage, (2) people who share will do so with those who previously shared, (3) reciprocal sharing relationships will spontaneously form. Along these lines, one thing that I like about the study is that the first author is an anthropologist and, in certain respects, the paper reverses the trope that some of us are accustomed to hearing with a certain degree of regularity from anthropologists, about how limited in value lab experiments with undergraduates are; Kapan et al. write: “Compared with field studies, the advantage of a laboratory experiment is its ability to implement sharper controls and narrow the interpretation of observations.” (p. 2).

Before summarizing the results, I just want to note that this sort of method seems to have tremendous potential. In addition to the fact that having subjects play video games probably makes it easier to recruit for later experiments, the advantage of this sort of study is that it allows interactions among subjects to emerge spontaneously and endogenously. If you thought that, for example, the idea that sharing high variance resources but not low variance resources was the result of a lengthy process of feedback on different norm regimes, then you might have been surprised to see this norm emerge so quickly in different groups of subjects. So, while the setting is controlled in a certain sense, there is also room for a lot of interesting dynamics among subjects.

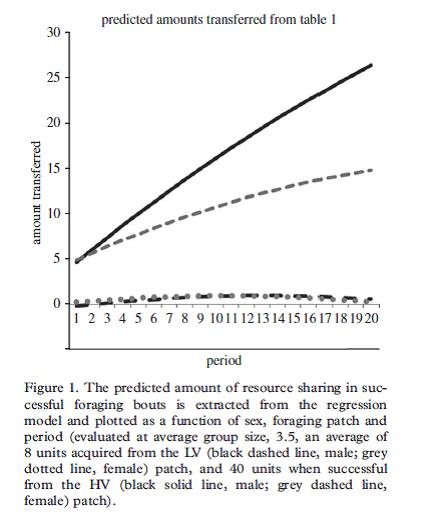

Figure 1 depicts some of the results, showing, based on their statistical model, the amount shared as a function of sex of subject and foraging patch (HV vs LV). Over time, the amount shared goes up, with sharing of high variance resources eventually dwarfing sharing of low variance resources. There’s also a sex difference (even though avatars were unisex).

The authors conclude that because theft was not possible, tolerated theft can’t explain why people transfer. Instead, they suggest, people are predisposed to identify gains in trade that are available in such ecologies, where I can buffer my bad fortune in period X by sharing my high variance resource in prior periods. People kept track of who shared with them, and subjects preferentially shared with these individuals. This was in the absence of any Hobbesian enforcement mechanisms to enforce covenants.

In their conclusion, they suggest that:

participants draw on social exchange adaptations to fashion a solution to a generic problem of risky and unstable return rates. The results also suggest that the current disinterest in pair-wise reciprocity in favour of alternative concepts, such as ‘strong reciprocity’, may represent a premature rejection of the most important developmental force in human cooperation; in spite of sex differences, welfare improves through sharing and people do not appear to throw away resources for display.

In any case, an interesting and, I think, important study. I look forward to more like it.

Citation

Kaplan, H. S., Schniter, E., Smith, V. L., and Wilson, B. J. (2012). Risk and the evolution of human exchange. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.2614

Comments (4)