It has been estimated that a quarter of the entire human population has seen at least one James Bond movie in their life. Nothing distills the Cold War Modern to its quintessence as well as the gizmo-wielding, martini-drinking, serially philandering British spy.

The flagrant individualism, the unbounded hope in the powers of technology, the clear cut black-and-white world defined by an epic battle between good and evil, the paranoia about the enemy within, so on and so forth. Geopolitics professor Klaus Dodds argues however, that much more cogent and immediate political resonances were buried in the actual geography of the early Bond films. It was the specific locales, and not simply the broad abstract themes, in which the political arguments of the Bond movies were embedded. The films defined geographies of fear and anxiety and contrasted them with spaces of comfort, security and belonging.

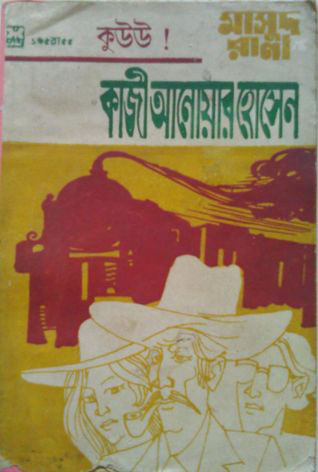

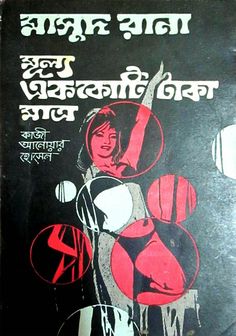

Masud Rana novels were no different. Born in the tumultuous 1960s in East Pakistan, Kazi Anwar Hussain’s adaptation of James Bond for Bengali audiences, also embedded complex political arguments in the geographic locations. But Rana’s politics was not Bond’s politics. Bond was fighting for a declining, but not yet dead, British empire. Whilst Rana fought for a Pakistani state still struggling to establish its territorial sovereignty and integrity. Early Rana novels sought to promote internal cohesion within the two geographically and culturally distinct wings of the then Pakistani state by creating imaginary technological threats which might render both wings equally vulnerable.  Simultaneously, the novels sought to promote a dis-identification between contiguous Bengali speaking areas which were not part of India by casting the geographic and cultural proximity as a source of vulnerability. Finally, the early Rana novels sought to undermine sub-national claims upon territory, such as those of the Chakmas in the Chittagong Hills, by asserting the areas strategic and technological importance of the nation’s common, shared future. In every case, the early Rana novels used complex technological plots to reimagine space.

Simultaneously, the novels sought to promote a dis-identification between contiguous Bengali speaking areas which were not part of India by casting the geographic and cultural proximity as a source of vulnerability. Finally, the early Rana novels sought to undermine sub-national claims upon territory, such as those of the Chakmas in the Chittagong Hills, by asserting the areas strategic and technological importance of the nation’s common, shared future. In every case, the early Rana novels used complex technological plots to reimagine space.

West Pakistan for instance, was ecologically vulnerable to annual locust attacks, but East Pakistan was outside the natural range of serious locust attacks. By imagining a biologically-modified locust created by the Indian Secret Service, one of the earliest Rana novels was able to create a shared territorial imagination that united both wings of the country by erasing the radical ecological dissimilarities between the two wings. Alleged Indian attempts to undermine Pakistani attempts to build a technologically challenging hydroelectric dam in the Chittagong Hills similarly provided the framework for the assertion of Pakistani national claims on the Chakma lands. In short technology and spatial politics were intricately aligned in these early Rana novels.

These early Rana novels deserve to be read, not just as light entertainment, but also a important political documents. Read more about the technospatial imaginaries of the Masud Rana novels.

a work written in a meaningful comprehensive article.

In a more immediate context, a very important question is just when Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson, the producers running the James Bond franchise, will officially announce Daniel Craig’s successor. Surely, it’ll be sometime after No Time To Die is released, which will only extend Craig’s record-setting run as the actor officially attached to the role.