Opaque, murky and shadowy are some of the metaphors one frequently has to invoke to describe the bygone era of gaslights. Yet, some of that past was also lucid and transparent. At least at first glimpse. Nothing exemplified that transparency and lucidity of the past than the diaphanous little images dubbed “transfer pictures” by the Victorians.

A British advertisement for ‘transfers’ in 1881

Transfer pictures seem to have their origins in the 18th century when a French printer and engraver named Simon Francois Ravenet developed a technique for quickly and accurately transferring images onto glass, pottery and other surfaces. The technique came to be known as decalcomanie or decalcomania. The pictures we are interested in however were not exactly these images, but rather a set of colorful images that became hugely popular amongst young children in the second half of the nineteenth century. These latter had to be dipped in water and then pressed on a surface for the image to be transferred. Though the name decalcomania, or “decal” for short, were often used for these water-sliding images as well, they were classed together with other “toys” for children rather than as something used by industrial potteries.

The images, which were mostly produced in Germany in the nineteenth century, were striking and colorful. Sold in sheets usually organized around a common theme, children would peel the individual images, dip them in lukewarm water and then press them face-down upon the surface they wanted to print on. This would transfer the image onto the new surface. Children used these to decorate scrapbooks, exercise books, and occasionally even their own skins. Though mass-produced and commoditized, the flexibility and ease of their use made them a mode of everyday and personalized aesthetic expression for the young.

Tomiolo’s ad published in The Pioneer in April 1882

Hartman’s ad published in The Pioneer in May 1883

Exactly when transfer pictures arrived in British India is difficult to tell with certainty, but by the early 1880s we find the famous Italian optometrist in Calcutta, G.M. Tomiolo, advertising the sale of recently-imported transfer pictures. Unfortunately, we have no records of what the subject of Tomiolo’s images was. Though his advertisements do suggest that the images were available in multiple sizes and to suit different tastes. Another early Calcutta seller, A. Hartman & Co., gives us a better sense of the prices. A large sheet of transfer pictures at Hartman’s cost 6 annas, while a dozen sheets together cost Rs. 3 and 2 annas. Hartman’s sets came contained between 20 and 400 pictures and were said to be “very amusing”. There is also some evidence to suggest that the prices began to fall rapidly. By the second half of the 1880s, Shircore & Co. of Cawnpore (Kanpur) were offering a “Monster Picture Packet” including 500 transfer pictures on varied themes and a range of other pictures such as small photographs, scrap pictures, and Japanese crape pictures for a mere Rs. 1 and 8 annas.

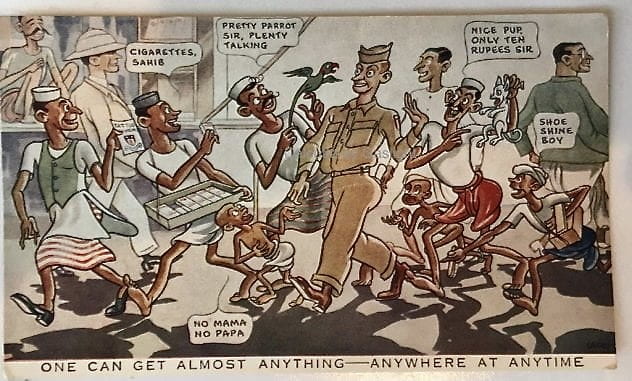

By the following decade, that is the 1890s, there also emerged Indian businesses that specialized in transfer pictures. One such trader was the firm of Roshanali Ebrahim of Colootollah Street, Calcutta. By the early 1920s transfer pictures had become so cheap and so far embedded in local trade that instead of being advertised and sold as independent commodities, they were often given free as promotional gifts along with other commodities. The Baghbazar Ink Factory, manufacturers of ink-tablets that could be dissolved in water to make ink for fountain pens, for instance, gave away free transfer pictures along with purchases around 1922. Indeed, by mid-1940s transfer pictures, often called ‘tattoos’ at the time, were also being hawked on the streets of Calcutta by itinerant peddlers. Calcutta cartoonist Merton Lacey depicted one of these ‘tattoo’ sellers on a small pocket calendar for 1945.

Bazar Postcard advertising Roshanali Ebrahim’s wares.

The emergence of a bazar-trade – and possible local manufacture – might also have had something to do with the health-scare around these pictures from the late 1890s. A widely publicized case, possibly in Germany, in 1896 of a young boy dying after licking several of these pictures brought to light the hazards of this seemingly innocuous hobby. It turned out that the bright colors were obtained by the addition of small quantities of lead. Though the manufacturers insisted that the quantities were minuscule and posed no real threat to children, authorities in Berlin began imposing strict regulations on the manufacture. Within a decade, by 1906, it was being reported that the German industry which had been concentrated in the Nuremberg area was reeling from the regulations and many of the biggest manufacturers had left the trade and shifted to other things. This opened up the door for the emergence of other manufacturers in other countries, including Britain, to fill the void.

Unfortunately, it is not clear what kinds of images were represented on the transfer pictures available in Calcutta. Most of the bazar traders possibly continued to import the pictures from abroad rather than manufacture them locally. But the images could still have represented local themes, as they did in the case of other cheap prints imported from Germany and Austria, such as postcards. Details about the prices charged in the bazar too are more difficult to come by as sellers like Roshanali Ebrahim did not advertise in the more high-brow, and hence better-preserved, newspapers. Yet there is every reason to believe that the emergence of bazar trade in itself might have encouraged a greater localization of the imagery and perhaps even instigated local manufacture.

We do have some serendipitously preserved evidence from the 1940s and 50s to show that by then the images being depicted on transfer pictures had been thoroughly Indianized. An old book of fairy tales that I picked up at a second-hand book store in Calcutta, for instance, has several transfer pictures pasted on various pages of it. Presumably the handiwork of the original child-owner of the book, these images depict a range of iconic Indian structures such as the Qutb Minar, the Red Fort, the Victory Tower at Chittor, the Meenakshi Temple at Madurai, and the Howrah Bridge. Unlike the multicolored images of the Victorian era, however, these are bichromatic images in red and blue, suggesting possibly the development of lower quality and cheaper local production.

These water transferable pictures for children were so popular in Bengal that in due course they were given a specific Bengali name – jolchhobi, literally, “water pictures”. I do not know if they acquired a specific name like this in any other language. In English, as we have seen already, they continued to mostly be called by a variety of names such as ‘transfer pictures’, ‘decals’, ‘water-slide decals’, ‘water-slide transfers’, and even ‘tattoos’. To the extent that giving something a specific name makes it immediately conspicuous and recognizable, the Bengali jolchhobi has clearly made these striking images a lot more discernible than they are for English-speakers. This discernibility has lived on long after the demise of the actual pictures themselves.

The rise of adhesive stickers and easy printing technologies from the 1990s seems to have killed off the transfer picture as a form of childhood entertainment and self-expression. Today’s children do not seem to play with them or even know of them any longer. Yet the term jolchhobi continues to be widely used. There have been multiple music albums, a few poems, and at least one film called jolchhobi. Most of these uses treat the name as a metaphor for the transparency and permanency of memories, but show little awareness of the colorful, magical images that were originally called by it. The transparency of the name itself seems to be a beguiling red herring. Beneath its seemingly obvious, but clearly misleading, evocation of pictures seen in or through water lurk the mostly-forgotten transfer pictures, only to spring their magic upon unsuspecting readers leafing through the yellowed and fraying second-hand children’s books picked up at some dusty old book store or discovered in a musty attic.

A “tatoo” seller (see far left) on the streets of Calcutta depicted on a Merton Lacey pocket calendar.

Delightful dive into the Victorian era’s “transfer pictures” and the art of decalcomania. The whimsicality of these colorful images, popular among 19th-century children, is beautifully captured. It’s fascinating to explore the intersection of art, technology, and play in history, revealing the nuanced facets of transparency in the bygone gaslight era.

Regards,