The Victorian world was one of clear contrasts and sharp hierarchies. White and black, good and evil, saints and sinners were all clearly distinguished and neatly stacked up. Or so the Victorians told themselves. But gaslights are not conducive to such clear lines. Shadows lurked, confusion prevailed and clarity was much more an aspiration than a reality. Identities, morals, and even facts were often confused and ambiguous. Jules le Grande’s was just such a tale of shadowy identities, mutable facts, and ambiguous morals.

It all began on the dark and dreary night of the 20th of October, 1890. On that night, as a group of poor working class men huddled together in their measly hovel in the small town of Nowgong in the princely state of Ajaigarh in Bundelkhand, they heard a commotion ensuing from one of the grander houses in their neighborhood. Stirred from their winter slumber by the commotion, the men decided to investigate. Upon reaching the house whence the commotion ensued, they were surprised to find the main door wide open. Inside, the men found a scene of bloody slaughter that would make their blood curl.

The house had belonged to an independent lady of means, one Raj Rani, who lived by herself. It was she who had been the object of the gruesome slaughter. Her right hand had been entirely chopped off. Her head alone had fifteen wounds and nearly been entirely severed. Somehow miraculously, despite the violence, Rani was still alive, though of course only barely. She expired soon after the men arrived. Murders were not uncommon in Victorian India, nor was violence. But Rani’s gaping wounds and the wanton violence upon her body testified to a degree of savagery that went well beyond what was expectable under such circumstances.

Scared by the sight, the men who found the body immediately alerted the local police. Since the murder had happened beyond British territories, the police were not the British India police but rather the local police of the Ajaigarh state. They arrived promptly and were accompanied by the local police chief, or to give him his actual designation, the Nazim.

The Nazim conducted the investigation with an alacrity that would have put the legendary Sherlock Holmes to shame. Within an hour or so of his arrival the Nazim had discovered a large number of tell-tale clues. First, there was a bottle of chloroform, a rag with chloroform on it, and a paper cone, all bundled under the poor victim’s bed. Second, behind the house was a rickety bamboo ladder. Third, in the courtyard was an empty scabbard. Somehow the Nazim’s men were able to identify all the things recovered as belonging to Jules le Grande.

Le Grande was known to be a drifter who had worked and lived in several princely states in the Bundelkhand region before taking up a job in the Ajaigarh engineering department at the salary of rupees 25 a month. It was said that he had gotten into some financial difficulties and hence tried to rob Rani. The murder was a consequence of the robbery.

The Nazim immediately proceeded to Le Grande’s house and arrested him there along with a woman he lived with and a visiting friend. Helpfully, the Nazim’s men were also able to recover the sword that belonged in the scabbard found at Rani’s courtyard. They were even able to match the dents on the blade to the dents on the bangles Rani had been wearing. Predictably some clothes belonging to le Grande were also discovered with blood stains on them. The case was as watertight as could be.

The only glitch arose when le Grande claimed that he was an American citizen and therefore could not be tried by the local court at Ajaigarh. Once this claim had been made, he had to be transferred to the jurisdiction of British courts presided over by the British officer who ran the so-called Bundelkhand Agency responsible for relations with the petty princely states of Bundelkhand. This was Colonel Wilson.

Now it so happened that the office of the Bundelkhand Agency was physically situated in the capital of Ajaigarh, namely, Nowgong. Hence the transfer of jurisdiction did not really entail a long-distance physical transfer. So there was no cause for delay. Col. Wilson too was keen to commence the trial. But le Grande’s claim to being an American complicated matters and the trial could not commence immediately. In fact, despite the speed with which the Nazim had solved the murder, the entire winter of 1890-91 passed without le Grande being put on trial. The issue of jurisdiction and what would a ‘jury of peers’ look like proved to be an almost intractable problem.

Eventually, after much delay and persuasion, le Grande agreed to be tried in Col. Wilson’s court with a jury of which at least half were to be European men. The trial commenced on March 14, 1891—perilously close to the ides of March—and concluded in little less than a month on April 7. Le Grande alleged that the entire case against him was fabricated by the Nazim who had a personal grudge against him. The evidence, he stated, had been planted and the blood stains on his clothes came from a cut on his own hand. There were other inconsistencies too. There was no plausible reason given for the excessive violence of the murder. Nor were robbed items ever recovered from le Grande’s possession. In fact, so far as the trial reports go, there was never any mention of an inventory of things robbed at all. Yet the entire butchery was said to have been perpetrated for the sole purpose of robbery.

Notwithstanding such inconsistencies and the all-too-neatness of the Nazim’s proofs, the jury took a mere five minutes to return a verdict of guilty. Col. Wilson immediately passed a sentence of hanging by death on le Grande.

Le Grande now appealed to the Governor General. But this appeal had to be forwarded through the Governor General’s Agent at Indore. Unfortunately for le Grande, the Assistant to the Agent at Indore, upon considering the verdict, declined to forward the appeal to the Governor General. With it, le Grande’s fate seemed sealed. But le Grande had not yet had his last say.

On the night of May 2, 1891, le Grande escaped from Nowgong prison. The jailor had been away that night, and the sentries keeping watch saw him sleeping peacefully on his bed. Only on the next morning, a Sunday, was it discovered that he had filled his prison clothes with bricks and laid them out on his bed as a decoy whilst he enlarged the cell drain and crawled through it to his freedom.

Such a brazen escape after such a widely reported trial was a huge embarrassment for the British authorities in Bundelkhand. A hundred sowars of the 8th Bengal Cavalry were immediately despatched post haste in hot pursuit. Newspapers across the subcontinent reported on the chase. But all to little avail. Three days later, the gallant sowars and their jaded steeds returned empty-handed.

New reports now began to emerge about the elusive le Grande. It was alleged that his real name was not Jules le Grande but Willie Campbell, and he was a swarthy Eurasian. Campbell had allegedly served time for robbery in Ajmer at one point and it was suspected that he may even have served time under other names in Allahabad and Saugor. Moreover, it was now alleged for the first time that le Grande might have been involved in earlier cases of murder as well but successfully eluded punishment.

Le Grande was now described as a master of disguise. A veritable chameleon who had in the past successfully passed himself off as “a Spanish nobleman, a French priest, an English squire, a mild Hindu and a savage Pathan”. His looks were described as that of an “Italian organ-grinder” and his walk that of an “Yankee”. He spoke a variety of languages with fluency and could allegedly change his countenance at will.

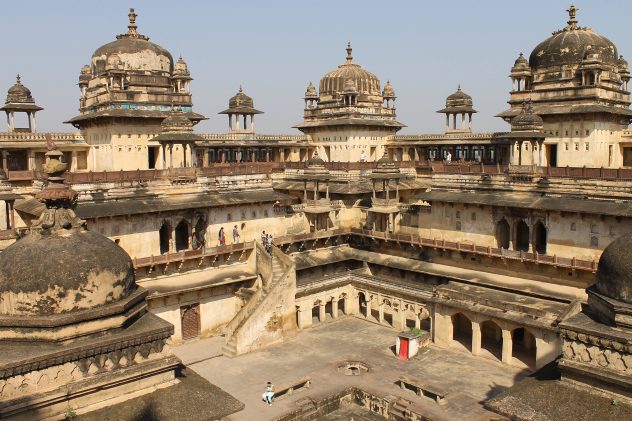

As stories proliferated and official paranoia blended seamlessly with sensational journalism to construct an image of an arch-criminal, le Grande’s run from the law proved shortlived. On May 8, 1891, a visibly distressed and disheveled man was found begging for food in the nearby princely state of Orchha. Arrested as a vagrant by the state police, it was not until a good four days had lapsed that he was identified as none other than the much sought-after le Grande.

From then on things went speedily and unspectacularly downhill for le Grande. He was sent, under a strong guard, from Orchha back to Nowgong on the 15th of May and on the early morning of the 22nd of May, he was executed at the Nowgong Jail. In marked contrast to the sensational headlines he had briefly generated not too long back, one newspaper simply reported the execution, tucked away in an unobtrusive column, under the header “Half-caste Murderer Executed”.

I do not know if le Grande was a murderous villain or a hapless drifter who managed to antagonize people way more powerful than himself. I do not even know if he was indeed called Jules le Grande or Willie Campbell. Yet, reading the official reports in the faint afterglow of the long-extinguished gaslights, there are many things that do not stack up. The savage butchery inflicted on Raj Rani and the apparent lack of any better motive than robbery, the neatness with which the recovered evidence implicated the condemned man, and the speed with which the case was pursued and the execution effected, all alluded to something that did not quite fit. Or, put another way, things seemed to fit too well. Too perfectly, much like well-laid plans often do. And so, questions hover like hungry ghosts. Who after all was Raj Rani? An independent, wealthy woman living alone at the time could not have been a very common phenomenon, and yet we hear so little about her. Likewise, how did the Nazim’s men so swiftly identify the items recovered from the crime scene as belonging to le Grande? What was the personal grudge that le Grande alleged the Nazim bore towards him? What became of le Grande’s partner and friend who were arrested with him? At one point some doubts were also raised about his escape and it was suggested that someone on the inside helped him escape. Who was this alleged helpmeet? Why do we not hear more about him or her? Above all, it is rare that infinitely resourceful arch-criminals find themselves so quickly reduced to such utter destitution and hapless begging at the turn of the tide.

Neither Indian nor European, le Grande drifted between worlds and across all sorts of boundaries. He most likely had walked the thin-edge of the law more than once, but I remain doubtful about his culpability in the murder of Raj Rani. He remains one of those minor characters who both bared and blurred the stark distinctions of the Victorian world. Eternally caught in the rims of that shadowy world, he reminds us at once of the malleability and opportunities the shadows allowed for reinventing one’s self and the injustices that awaited those who could not belong to the light.