When Prometheus stole fire from the gods, we do not know in what form he actually carried the fire. Most denizens of gaslit cities, however, carried fire in their pockets. That is, in the form of a box of matches. Calcutta was no different. Though local match production in the city did not acquire significant dimensions till after the First World War, throughout the late nineteenth century Calcuttans of every stripe used matches. These matches were imported from Sweden, Austria, Bohemia, and later Japan. A number of pioneering businessman engaged in this import trade. Some of the most successful ones eventually set up their own production units abroad as well and created large, transnational business firms. One of the most successful amongst these men was a Parsi gentleman called Mr. M.N. Mehta.

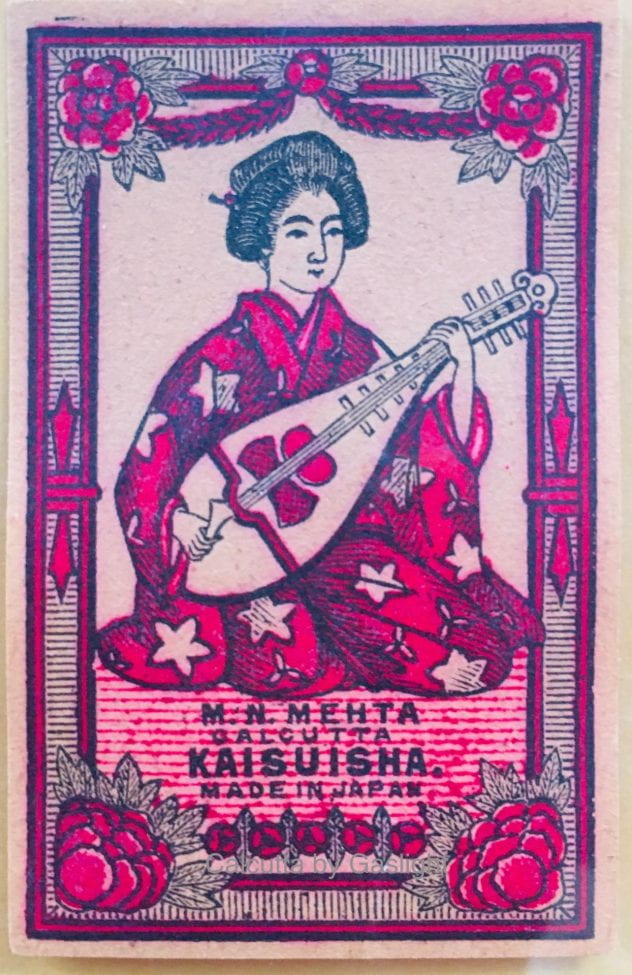

Merwanjee Nanabhoy Mehta was born in Bombay in 1857. After finishing his schooling at the Bombay High School, he initially moved to Calcutta for college but then made the city his home for the rest of his life. He attended the St. Xavier’s College in Calcutta. Two years after finishing college in 1877, in 1879, he joined a small trading company at a modest salary. An ambitious man, the young Mehta did not remain at the firm for long. Instead, with with the help of his uncle, Edalji Naoroji Mehta– at the time an established businessman in China, the young Merwanji aged only twenty years, invested the small capital he had in the China trade. Initially, he imported glass bangles from the Qing empire to the Raj. His business flourished and Merwanjee soon began to diversify his portfolio. While keeping a toe in the China trade, he was soon importing things from Austria, Germany, Great Britain and Japan as well. With the money he made, he also briefly then attempted to set up manufacturing businesses in India. He established a glasswork in Calcutta called the M.N. Mehta Glass Works and a match-making establishment in Ooty. Unfortunately, the manufacturing businesses did not flourish and Mehta soon abandoned them, preferring to focus instead on the import trade. Mehta’s success in the international trade was truly unparalleled. In 1897 he travelled to China and set up offices in Canton. Later, in 1915 he opened offices in Kobe, Japan. By the end of the Great War, Mehta’s business empire stretched from Bohemia to the Land of the Rising Sun. He owned multiple large properties in both Canton and Kobe, apart from in Calcutta. Mehta was therefore one of the key players through whom the Bohemian domination of the Indian match-market was eclipsed by a near-total Japanese monopoly around the dawn of the twentieth century.

When Mehta eventually died on the 14th of July, 1928, he was one of the wealthiest men in the Raj. By that time however, the networks of international trade that had evolved since the late nineteenth century were also in the process of being radically transformed. A combination of new economic policies pushed through by local manufacturing interests such as the Birlas, with support from the powerful new nationalist politicians, and the effects of the Great Depression, led to the demise of many of the international networks of trade that businesses such as Mehta’s depended on. Upon Mehta’s death, his son Pirojshah inherited the massive empire, but not one that was well placed to survive in the new, more nationally oriented commercial age that was emerging. Unfortunately, Pirojshah was not able to replicate his father’s success in this rapidly changing environment and the Mehta enterprise began to collapse with remarkable speed. The massive, multinational business empire that the enterprising Merwanji had established from scratch did not even survive a decade under Pirojshah’s stewardship. By 1935, a mere seven years after Merwanji’s death, the entire business was finally wound up.

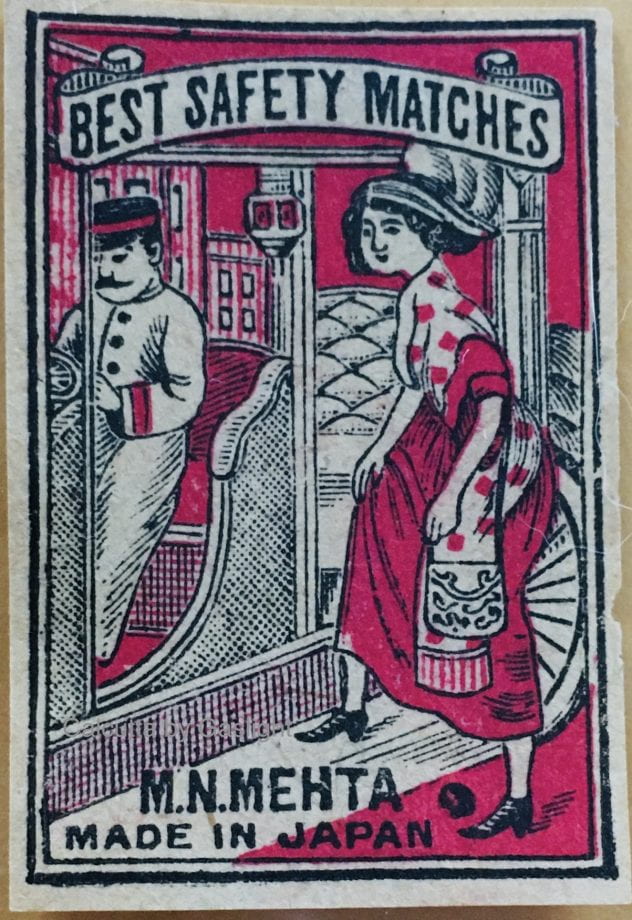

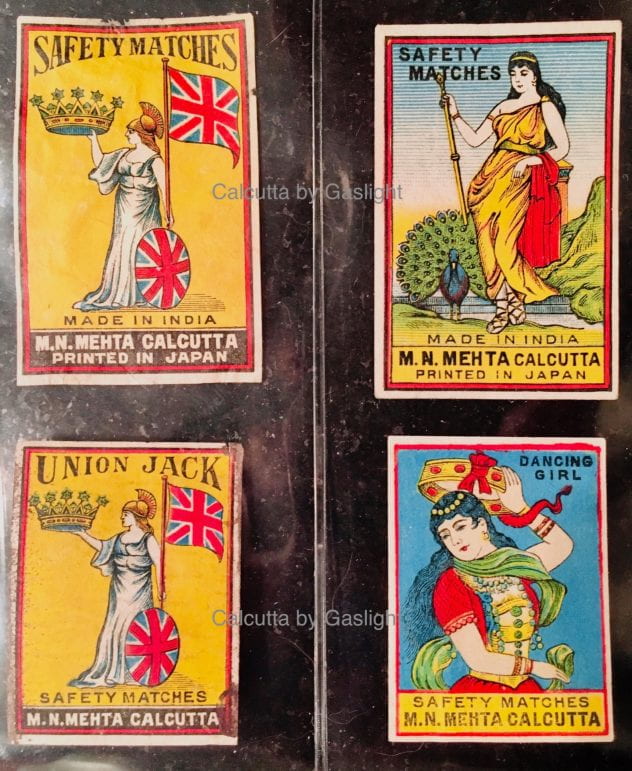

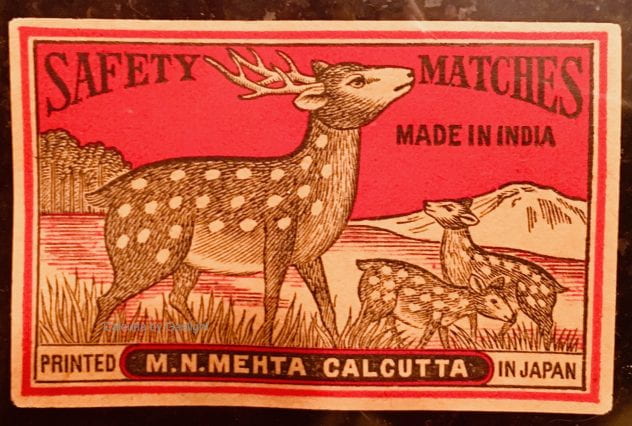

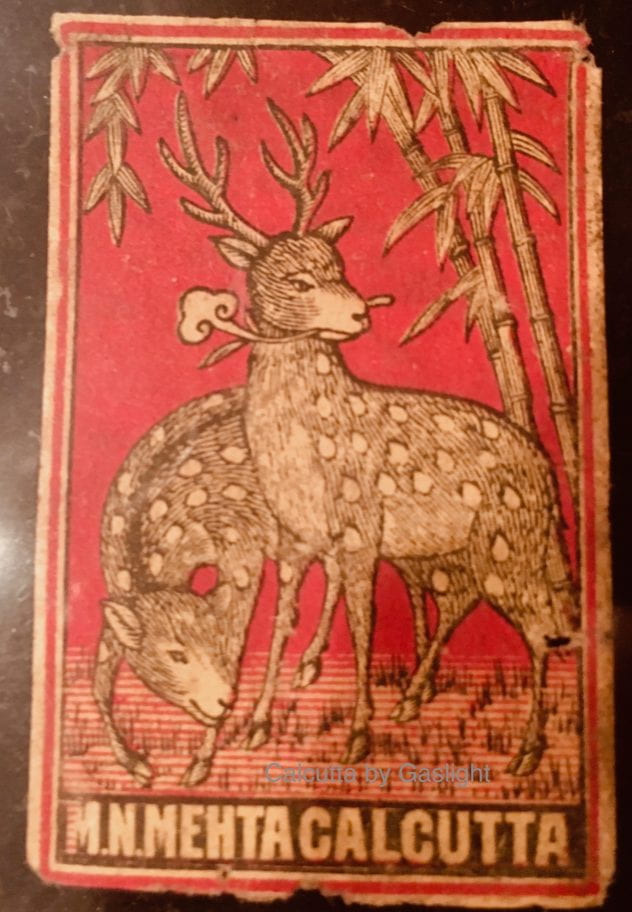

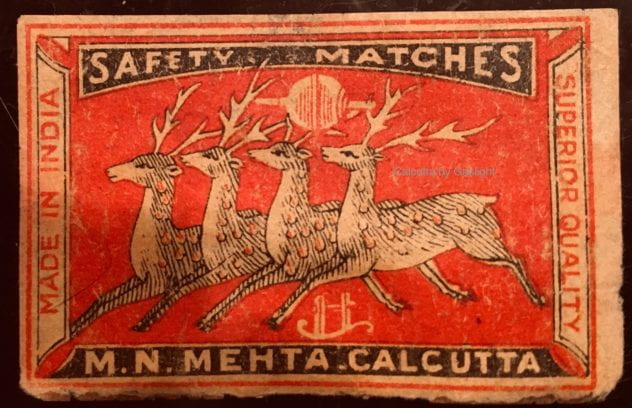

Merwanji Nanabhoy Mehta’s success also bore the distinctive hallmarks of the age in which he thrived: an age marked by a fascinating dance between empire and nation, between cosmopolitanism and localism. Parsi business had embodied this bivalent world, somehow holding together in their person and in their businesses, the contradictory pulls of those times. Indeed, Mehta had belonged to a generation of Parsi stalwarts such as Dadabhai Naoroji and shared the latter’s dual commitment to both the British Empire and Indian nationalism within the Empire. The Mehta family in fact hailed from Navsari, the very town where Naoroji had been born and the ancient town’s cosmopolitan ethos might well have equally influenced both men. Mehta’s matchbox labels, some of the most beautiful one can find from the era, bear testimony to this bivalent politics. Images of Britannia and the Indian National Congress both appear with equal frequency. Indeed he even explicitly advocated the boycott of foreign-made goods and the use of Swadeshi goods.

Merwanji Nanabhoy Mehta’s success also bore the distinctive hallmarks of the age in which he thrived: an age marked by a fascinating dance between empire and nation, between cosmopolitanism and localism. Parsi business had embodied this bivalent world, somehow holding together in their person and in their businesses, the contradictory pulls of those times. Indeed, Mehta had belonged to a generation of Parsi stalwarts such as Dadabhai Naoroji and shared the latter’s dual commitment to both the British Empire and Indian nationalism within the Empire. The Mehta family in fact hailed from Navsari, the very town where Naoroji had been born and the ancient town’s cosmopolitan ethos might well have equally influenced both men. Mehta’s matchbox labels, some of the most beautiful one can find from the era, bear testimony to this bivalent politics. Images of Britannia and the Indian National Congress both appear with equal frequency. Indeed he even explicitly advocated the boycott of foreign-made goods and the use of Swadeshi goods.

Even more interestingly, Mehta’s nationalist labels were not only explicit in their advocacy of economic nationalism, but printed entirely in Bangla, rather than English. Whether this was merely a shrewd businessman trying to cash into a strong sentiment for consuming locally made products, or a genuine commitment to promote both the local and the imperial side by side is difficult to tell. What was clear however, was that Mehta’s businesses were not amenable to any easy historical pigeonholes.

Mehta’s personal cosmopolitanism was engendered in his wide travels. He was in fact a true globetrotter. We have already seen that he had travelled to China since the late nineteenth century. In 1905, the very year that the Swadeshi Movement was re-emphasizing localism, Mehta travelled to Japan, Europe and the United States. He travelled to Japan again in 1915, in the midst of the Great War. Few Calcuttans of the time would have been as widely travelled as Mehta.

Unfortunately, today both the non-dichotomous and nuanced politics that men like Mehta espoused and the enormous mercantile success they achieved have largely been forgotten. But the strikingly beautiful match labels continue to bear testimony to the cosmopolitan life of this Promethean Parsi from Calcutta.

great write-up, and wonderful images. Wonder what the word ‘impregnated’ above Victoria Memorial refers to!

Thanks! Glad you liked it.

“Impregnated” was used in the sense of “infused”, viz. the wood was infused with the chemicals (sulphur or phosphorous) and hence the matches lighted up easier than one other matches.

Interesting article indeed and beautiful match box illustrations!

Thanks for reading, Karin. Glad you enjoyed it.

Great read. Thank You.

I wanted to take a moment to express my heartfelt gratitude for your enlightening article on The Promethean Parsi. Your insightful exploration of the intersection between culture, identity, and the pursuit of knowledge truly captivated my attention. Your meticulous research and engaging writing style brought to life the remarkable contributions and resilience of the Parsi community.

Enjoyed the read, thanks. Especially a Parsi Mehta born in Calcutta in 1958!

I was wondering if any of the actual matchboxes depicted were available for purchase online or otherwise?

Viraf

Dear Viraf,

Thanks for reading. I have most of the matchboxes depicted here. Some of them can still be obtained from specialized sales and auctions. There are quite a few old matchbox collectors and so if you keep a look out, I’m sure you can find quite a few of these in time if not all.

Good luck,

Projit

Great information guys