Many ancient religions look upon fire with reverence, but no other religion has elevated it as high as Zoroastrianism. Atash, or the Holy Fire, is not only a hallowed medium through which spiritual insights become available to humans, but it engenders the very visible presence of Ahura Mazda, the supreme deity. With such an exalted view of fire within their cosmogony, it is hardly surprising that Zoroastrians would be amongst the first to recognize the importance of the new firesome technology of the matchstick. And who better amongst them to embrace this novelty than the traditional priesthood devoted to the veneration of Atash.

Though Parsis had played an important role in the emerging commercial landscape of the British imperial capital at Calcutta since the mid-eighteenth century, they did not build a temple in the city until 1839. The first Zoroastrian Fire Temple (agiary) was consecrated in that year at 26, Ezra Street. The Seth Rustomjee Cawasjee Banajee Kadimi Atash Adaran, as it was called, had been established by the eponymous Rustomjee Banajee, a pioneering merchant who had moved to Calcutta from Surat. Expectedly, upon setting up the Fire Temple, he brought priests from his native Surat to officiate at the new agiary. Of the three priests who came, the head priest was Ervad Framjee Pestonjee Nalladaroo. Framjee Pestonjee officiated as the high priest of the temple for five years before venturing into business.

Though Parsis had played an important role in the emerging commercial landscape of the British imperial capital at Calcutta since the mid-eighteenth century, they did not build a temple in the city until 1839. The first Zoroastrian Fire Temple (agiary) was consecrated in that year at 26, Ezra Street. The Seth Rustomjee Cawasjee Banajee Kadimi Atash Adaran, as it was called, had been established by the eponymous Rustomjee Banajee, a pioneering merchant who had moved to Calcutta from Surat. Expectedly, upon setting up the Fire Temple, he brought priests from his native Surat to officiate at the new agiary. Of the three priests who came, the head priest was Ervad Framjee Pestonjee Nalladaroo. Framjee Pestonjee officiated as the high priest of the temple for five years before venturing into business.

Framjee Pestonjee’s son, Nawrojee Framjee, was apparently the first Parsi to have been born in Calcutta. Along with his elder brother, Byramjee Framjee, Nawrojee joined his father in business at an early age and in 1870 they formed the F.P. Nalladaroo & Co. The company traded with Italy and Czechoslovakia in the west and China and Japan in the east. The Nalladaroo brothers, and especially Byramjee, were also keen sportsmen. They were founding members of the Parsi Club, originally founded as a cricket club, as well as instituting the Byramjee Nalladaroo Memorial Tennis Cup.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, F.P. Nalladaroo & Co. became one of the first importers of Japanese matches. The firm’s offices were initially at 50/1, Canning Street, and their trading portfolio included, besides matches, rubber, bees wax, musk, and glass bangles. By 1918 however, they had moved to 60, Bow Bazar Street, immediately next to the offices of the famous Bengali inventor and entrepreneur, H. Bose, and his Kuntaline Press.

It is not yet clear how long the firm continued in the matches business, but they were certainly still in business after the First World War. We hear of them as important importers of matches up until the early 1920s, though they may well have continued longer. It was of course during these interwar decades that local match production in Bengal began to grow. During the period of roughly half a century during which the firm of F.P. Nalladaroo & Co. operated, they changed their name twice. Initially, they simply shortened the spelling to F.P. Naladaru & Co., but later changed the name more completely to Nalladaru Brothers.

Throughout this period, they also set up a number of branches throughout east Asia. In 1905 for instance, they had branches in Canton and Hong Kong. But by 1912 the Canton office seems to have closed. The Hong Kong office however, continued to function into the 1920s. During this period several other Calcutta firms, including the other hugely influential Parsi firm of Merwanjee Nanabhoy Mehta also competed for the same east Asian trade. As a result, around 1912 the two biggest Parsi match importers of the city, F.P. Nalladaroo & Co. and M.N. Mehta & Co., got embroiled in a long-running legal battle.

Another interesting aspect of the Nalladaroos operating in east Asia was Nowrojee Framjee’s medical career. Nowrojee had qualified as a homeopath in Calcutta and had been involved in some of the efforts being made in the city and the colony more generally by British Indian homeopaths to professionalize themselves. During his stays in east Asia, he continued to practice homeopathy and even opened up a separate medical practice alongside his business operations. By 1907 he thus had a medical practice at 14, Lyndhurst Terrace in Hong Kong, in a building that also housed one of the two offices of F.P. Nalladaroo & Co. in Hong Kong.

Another interesting aspect of the Nalladaroos operating in east Asia was Nowrojee Framjee’s medical career. Nowrojee had qualified as a homeopath in Calcutta and had been involved in some of the efforts being made in the city and the colony more generally by British Indian homeopaths to professionalize themselves. During his stays in east Asia, he continued to practice homeopathy and even opened up a separate medical practice alongside his business operations. By 1907 he thus had a medical practice at 14, Lyndhurst Terrace in Hong Kong, in a building that also housed one of the two offices of F.P. Nalladaroo & Co. in Hong Kong.

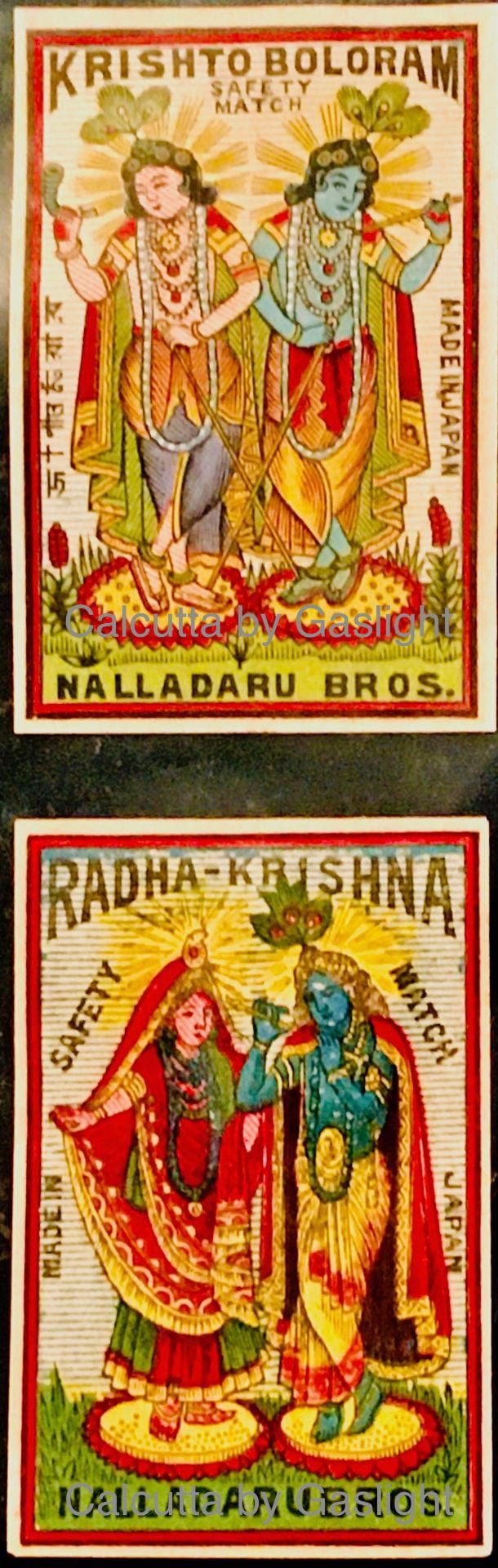

The matchbox labels of the Nalladaroos were strikingly beautiful as well as distinctively Bengali. Notwithstanding their Surti roots, the family seemed to have embraced their Bengali identity. Not only were the legends on their match labels written in Bengali and English, but they also frequently depicted specifically Hindu Bengali deities. This was particularly in contrast to other Bengali match importers with roots in Gujarat, such as the Essabhoys, whose labels frequently depicted Gujarati Hindu deities.

The matchbox labels of the Nalladaroos were strikingly beautiful as well as distinctively Bengali. Notwithstanding their Surti roots, the family seemed to have embraced their Bengali identity. Not only were the legends on their match labels written in Bengali and English, but they also frequently depicted specifically Hindu Bengali deities. This was particularly in contrast to other Bengali match importers with roots in Gujarat, such as the Essabhoys, whose labels frequently depicted Gujarati Hindu deities.

The match-trade in Calcutta was dominated by expatriate family firms. The Essabhoys, the Karimbhoys, the Mehtas, the Bakhsh Ellahies, the Adamjees, and many others came from elsewhere and made the city their home. By expanding their businesses into central Europe and eastern Asia they connected Calcutta to a much larger commercial and cultural geography than simply that of British India. Through them Bengalis accessed and learnt the use of the new fiery tool. Mundane habits such as smoking, lighting, and cooking were forever transformed. Equally, in the process, these families too sank roots and became Bengalized to varying degrees. The Nalladaroos were not exceptional in following this pattern, but the extent to which they embraced the city and its cultural idioms remains unmatched. It is thus all the more saddening that after glowing so brightly through those dimly gaslit decades, they disappeared so thoroughly in the glare of the electric lights that followed. Then again, that’s the thing with a matchstick. It burns brilliantly but all too briefly.