Blazing fires cast bright lights. Bright lights evoke stark, hard edges. The gaslit world of shadows is its opposite. Edges appear blurry and ill-defined. Mystery, romance and magic are its bywords rather than definition, clarity and certainty. The year 1857 was a year when the flickering world of shadows was abruptly supplanted by a towering inferno of violence and hatred. Till this day, it is difficult to look towards that year without having to shield one’s eyes from the lurid brilliance of funeral pyres. The line between friends and foes seemed all too obvious and the chance of anything existing in the middle utterly impossible.

Mercifully, blazes that burn too brightly usually go out quickly. So too did 1857. A new dispensation emerged. Some things changed, some didn’t. People counted their losses, heaved a sigh of lament and got on with the business of getting used to the new rhythms of life. The memories of the conflagration of 1857 began to gradually lose some of its deathly pallor and acquire the softer, yellowish tinge of nostalgia. By the 1880s a new generation had grown up since that fateful year and the world had moved on towards gaslights, both metaphorical and real.

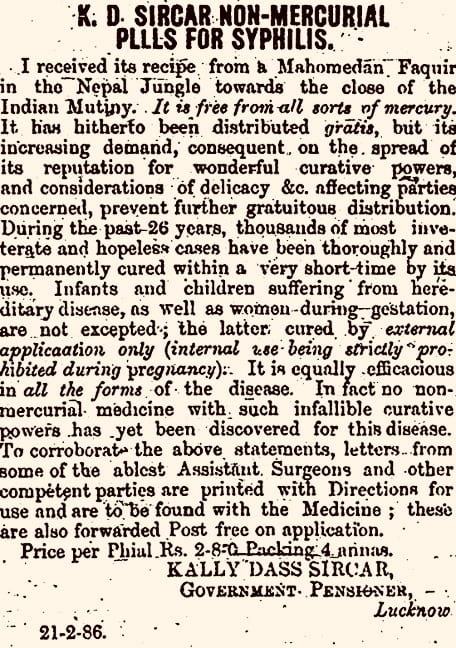

It was in that world of the 1880s that Kally Dass Sircar chose to remind people of the eruptions of 1857. The reason he did this was not to contribute to the then newly emerging nostalgia market for reminiscences of those fateful events. Rather, he did it for the much more practical purpose of selling his medicine, namely, K.D. Sircar’s Non-Mercurial Pills for Syphilis.

Day after day for nearly half a century Sircar ran a lengthy advertisement in newspapers across northern India, from Lahore to Calcutta, offering his pills for sale to the public. The story of these pills, it seemed, were tied up with the events of 1857. Sircar announced that the pills–or their secret–had been given to him by a “Mahomedan Faquir in the Jungles of Nepal towards the close of the Indian Mutiny”. He went on to describe the “wonderful curative powers” of these pills and how over the past 26 years he had helped thousands of men, women and children suffering from the effects of syphilis freely with the medicine. The great virtue of the pills, it seemed, was that they were entirely free of mercury, usually a key ingredient in medicines for syphilitic and other venereal diseases.

The growing reputation and demand that, according to Sircar, had followed from his success had made the continued gratuitous distribution of the remedy impractical and therefore he now chose to offer it for sale to the general public at a modest price. Sircar offered testimonials from government-employed Assistant Surgeons regarding the efficacy of the drug and, in order to prove the bona fide of his claims, signed off by stating that he himself was a “Government Pensioner” residing in Lucknow.

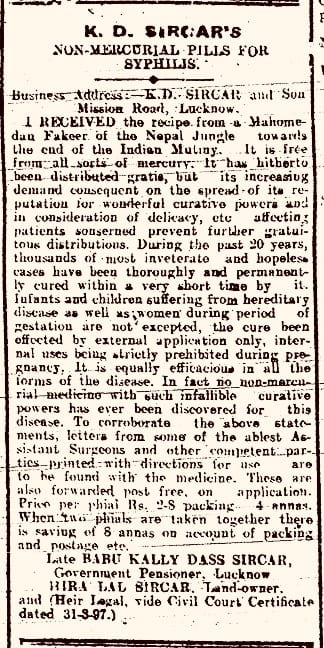

Kally Dass Sircar likely passed away at the very dawn of the twentieth century. But his pills lived on. His son, Hira Lall Sircar, continued to advertise the pills in largely the same vein, only adding the full judicial reference to the certificate of inheritance by which he had obtained his father’s estate. The original lengthy text with which Kally Dass had offered his pills to the public in the mid-1880s continued with only minimal alterations till the Great War under Hira Lall’s name. The advertisements were still to be found in northern Indian newspapers in the early 1920s.

Kally Dass Sircar likely passed away at the very dawn of the twentieth century. But his pills lived on. His son, Hira Lall Sircar, continued to advertise the pills in largely the same vein, only adding the full judicial reference to the certificate of inheritance by which he had obtained his father’s estate. The original lengthy text with which Kally Dass had offered his pills to the public in the mid-1880s continued with only minimal alterations till the Great War under Hira Lall’s name. The advertisements were still to be found in northern Indian newspapers in the early 1920s.

In the latest advertisements in the 1920s, finally, after almost half a century, the lengthy text was abbreviated. Reduced from a somewhat prosaic paragraph to a pithy sentence now, it still proclaimed that the pills, which were available from Mission Road, Lucknow, were “supplied by a Mahomedan Fakir during the Mutiny”. By the 1920s of course much had changed. Nationalists were fighting to rid the country of British imperialists. Hindus and Muslims were increasingly being mobilized against one another. Even the spelling of Sircar’s name had changed to Sirkar. Yet, through all these changes Sircar’s pills had continued to repeat a story that brought together a Hindu man, a Muslim fakir, and loyal service in the British imperial government without any sense of incongruity.

Even as rival sides, by the 1920s, were already telling increasingly partisan stories about the violence of 1857, Kally Dass and his son Hira Lall continued to evoke a more ambiguous set of memories. Unfortunately, we cannot tell if these memories recalled a real encounter in the Nepalese jungles or was merely a piece of advertising fiction. Irrespective of such parsing out of fact and fiction, what we must admit is that the memories retained a public purchase for nearly half a century. In them flickered a world of mystery, romance, and fuzzy boundaries, rather than the stark antagonisms of historical writing.

That Sircar was a denizen of Lucknow, the city at the very epicenter of the conflict is even more poignant. One wonders when Lucknow burnt, why was a loyal government servant like Sircar in the Nepalese jungles? Was he perhaps on a secret mission to track down the rebel leader and deposed Peshwa Nana Saheb who was supposed to be hiding in the jungles of Nepal? Who was the fakir and why did the fakir divulge this valuable remedy to Sircar? If there is more than a touch of the Kiplingesque in such flights of fancy, this is hardly surprising. After all, Kipling himself was a young journalist in the very region where Sircar was running his advertisements. It is almost certain that Kipling himself would have read these advertisements. Are the similarities between the hints of espionage and mystical healing we glimpse in Sircar’s advertisements and Kipling’s Kim entirely serendipitous?

And what about Hira Lall? Why did he have to get a legal certificate to recognize him as his father’s heir? Was he perhaps adopted from a family butchered in the conflict like Tagore’s Gora?

Or perhaps all of it was just a huckster’s ingenious lie?

We will never know. The answers lie forever buried in the shadows of gaslights.