The soft blurry edges of a world lit by gaslights was as much a reality as a metaphor for the world of the nineteenth century. The overly crisp outlines and hard edges of the later world of fluorescent lighting were unavailable to the world of the nineteenth century. Perhaps nothing more conspicuously captured this blurriness than the grand ‘festival’ of Muharram.

Muharram in Calcutta

Muharram in Calcutta

According to standard definitions, it is hardly a ‘festival’. It should be an occasion to lament the cowardly murder of Imam Hussein, the grandson of the Holy Prophet, on the battlefield of Karbala, by the evil Shimr. But by the nineteenth-century, it had taken on something of a carnivalesque aspect in urban settings like Calcutta. While forms of spectacular self-flagellation remained conspicuous, the massive processions, special decorative objects like taziahs and taboots, large-scale feasting, and perhaps above all, the demonstrations of sword and stick-fights, turned the occasion into something of an urban carnival. Interestingly in recent times anthropologist Annu Jalais has found Bengali Shias distinguishing between their own more sombre observation of Muharram and the more boisterous, carnivalesque Muharram of lower-status Sunni ‘Biharis’. It is doubtful, however, whether any such attempts to distinguish “proper” Bengali Shi’i Muharram from “improper” Bihari Sunni Muharram were ever made in the nineteenth century.

A nineteenth-century Muharram procession in Dhaka

A Muharram procession in Calcutta

Likewise, while standard definitions identify the observances mostly with Shi’ite Islam, both British and Bengali observers aplenty noted that the crowds that assembled in the processions or performed the various acts of self-flagellation came from all walks of local society, including significantly large numbers of Hindus. The famous Bengali essayist, Annadashankar Ray for instance, recalled that his grandmother had taken a vow to have him, her grandson, engage in a stick-fight during Muharram if her wish was granted. A more obscure memorialist, Satkarpati Ray, recalling his childhood in a smaller Bengali town, also mentioned how Hindus and Muslims both participated in the sword and stick-fights as well as the processions. The only sectarian conflicts he noted were between different neighborhoods (paras) over their processions.

Finally, the actual practices of Muharram also seem blurry. One of the most visible aspects of the Bengali Muharram, for instance, was a form of self-flagellation that involved sealing one’s mouth shut with a modified horse bit or a small spit with a lock. The person who had thus locked her/ his mouth would then perambulate the Imambara’s cenotaph waiting for the lock to fall off. If it did so in the third or seventh perambulation, it was held that the wish would be granted. M. Garcin de Tassy reporting on the practice said that this, along with a bunch of other related practices, was clearly borrowed from the “mummeries of Hindu fakeers”. Whether borrowed or not, the practices clearly shared some resemblances for observers like de Tassy that made them seem connected.

Yet, notwithstanding all the blurriness nor the fact that it was in fact a global event observed across much of Afro-Asia and parts of Europe, the Bengali Muharram also had a distinctive flavor. The taziahs that were carried during the processions were one such local aspect. Made of bamboo, fine paper and tinsel, these large architectural models are meant to represent the tomb of Imam Hussein. Yet they look nothing like the funerary shrine at Karbala. These models seem to be specific to Indian Muharram observances. Historian Pushkar Sohoni points out that even the name, taziah, though drawn from an Arabic root, is peculiar in its Indian usage. In Arabic, the word generally refers to the mourning practices of the Arabic-speaking Shi’is in general. In Persian, it refers to passion plays that reenact the tragedy of Karbala. It is only in India that the word has come to refer to these architectural models. Even more interestingly, Sohoni observes that while in northern India these models are eventually buried at the end of the procession, in western India they are immersed in waterbodies with much fanfare just like the immersion of Hindu idols. Moreover, the actual designs of these taziahs in western India also seem to be akin to eighteenth-century Hindu temple architecture. It remains to be seen whether Bengali taziahs bear similar resemblance to local temple architecture.

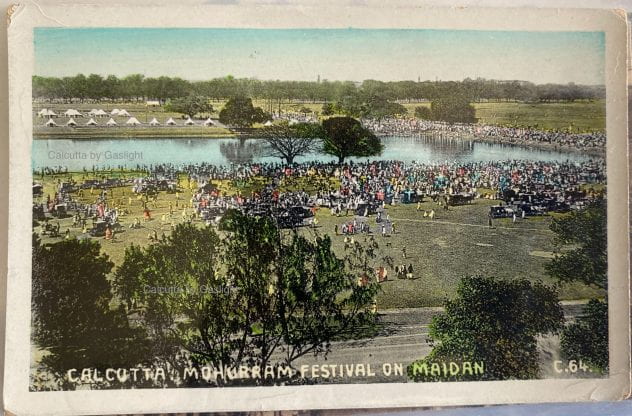

Taziahs on the Maidan, Calcutta

Of all the practices, the one most distinctively Bengali aspects was the stick-fighting or stick-dueling (lathi-khela). A stylized jousting with long, characteristic sticks or poles, the practice was a blend of sport, entertainment, martial art and fitness regime. How it came to be incorporated into Muharram observances is difficult to track with precision, but it was by the nineteenth century a quintessential feature of Bengali Muharram. The centrality of this practice to Bengali Muharram is borne out by the fact that it was also depicted on locally produced postcards.

While postcards depicting Muharram are fairly common and provide a rich visual archive for the occasion in a variety of urban contexts across British India, the vast majority of these depict processions, taziahs, taboots, and such. The only exception to this restrictive visual vocabulary that I know of are the Bengali “stick-dueling” cards. It is thus a delicious historical irony that in these cards, a historically literate printer’s devil illuminatingly rendered ‘dueling’ as ‘dwelling’!