On the 30th of May 1867, a worried father walked into the Entally police station. No name, leave alone an image, of the paternal figure has survived. But it is not impossible to imagine the deep disquiet that would have hung heavily, like the mid-summer sweat, upon his aged brow. The prospect of having to deal with the colonial police force would have likely done little to assuage his perturbation. It was exactly a decade since the conflagration of 1857 and the Capital’s police force was still organized along quasi-military lines. Entally, along with Chitpur, Bhabanipur, and Garden Reach were each placed under an independent Superintendent of Police, while men bearing military ranks ran the Calcutta Police itself. In short, the police force was a daunting militaristic institution and not one to which common people turned for help if they could avoid it. Yet, this was precisely where our worried father went. It was his last resort.

His young son had been missing for a few days now and the old man, despite his best efforts, had failed to locate the youth. The missing lad was a young healthy man in his twenties and had returned only recently from a trip to Mauritius. A few days ago he had stepped out to meet an old acquaintance of his, Apoo. That was the last the old man saw his son. Having first waited and then looked all around for his son, he had finally turned to the police.

Two days later, on the 1st of June 1867, a constable came by and asked the old man to accompany him to the police ‘dead-house’, as the morgue was then called, in Alipur. Alipur and Entally were entirely distinct suburbs of a fast-growing Calcutta at the time. Not to mention a long way off. We can only imagine with what foreboding and trepidation the old man must have made his way to Alipur. The agonizingly long journey along roads baked by the heartless summer sun must have transformed the brooding sense of dread into an overwhelming desolation. Once there, his worst fears came true as he recognized the badly decomposed corpse he was shown to be that of his dear son.

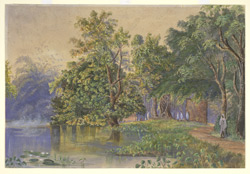

The young man’s corpse had been found that morning in a pond within a large garden in Entally owned by Apoo. At the time of discovery the corpse was already badly decomposed but it still bore the distinct marks of a physical assault. There were stab wounds on the forehead, the left arm, and the shoulder. The police had arrested Apoo and some others connected to him and transferred the body to the morgue, pending identification.

The officers at the morgue, as soon as the old man had identified his son, registered a case of possible homicide and asked the Entally police to release the body for a post-mortem. Notwithstanding these instructions, however, the Entally police cremated the corpse soon after. They also inexplicably released the suspects they had apprehended.

Major Reveley, then Deputy Commissioner of Calcutta Police, upon reviewing the homicides in the city came upon the case and attempted to follow it up. It was then that he realized the corpse had been cremated without a post-mortem and the suspects released without any charge. Upon further inquiries, he found that one of the suspects apprehended at a neighboring police station had actually begged to be sent to Entally since, as the man put it, he “knew the sahib there”. An irate Major Reveley immediately took up the inquiry personally.

To his great consternation, he found that the Superintendent of Entally Police, Mr. Joseph Younan, and the investigating officer were both clearly corrupt and had been heavily bribed. The culprit, Apoo, was a wealthy Chinese man who owned a large estate in Entally. He was also in love with a beautiful Bengali woman named Fulia, whose brother, Khetra, owned a local sweetshop. In fact, both Fulia and Khetra had witnessed the murder.

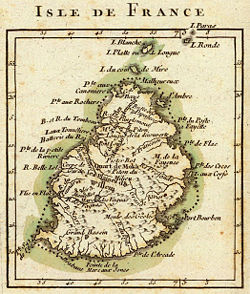

The unnamed dead man was also a member of Calcutta’s small Chinese community. The two men, both Calcutta Chinese, had possibly met for the first time in Mauritius. Mauritius, at the time, had begun importing indentured labor from India. A few local businessmen had followed the labor trail to the island. Some had even become labor contractors themselves. A few of the Calcutta Chinese were also involved in these ventures and it is likely that it was one of these business ventures that had taken Apoo and his victim to Mauritius. Both had after all travelled back and forth from the island to Calcutta for relatively short durations and appear to have been comfortably off in Calcutta. All circumstances that suggest they were businessmen rather than indentured laborers.

The Chinese community in Calcutta had been growing since the eighteenth century. By 1857 there were about 500 people of Chinese descent living in Calcutta. In the city, they were concentrated around the neighborhoods of Dharmatala and Kashaitala. Most of them were ethnic Hakka hailing from around Meizhou in Guangdong. In Calcutta, by the middle of the nineteenth century, they worked as shoemakers, carpenters and hogslard manufacturers. British imperial policy had vigorously promoted the consumption of opium in China as a cynical financial enterprise. The Calcutta Chinese too had been affected by this growing culture of opium smoking leading a handful of them to open up opium dens in Calcutta. With the opium had come the gambling dens. The city’s Chinese community had thus developed a seamy underbelly nurtured by the imperial appetite for ever-larger profits.

Apoo ran one of these clandestine gambling dens in Calcutta. Major Reveley found three witnesses who would testify at the trial. These included an unnamed gardener who worked for Apoo, an Indo-Portuguese man named Rodriguez who too worked for Apoo, and most dramatically, Khetra. The picture that emerged from their testimonies was a staggering portrait of lurid vice, reckless violence, and utter lawlessness. On the night of the murder, the dead man along with a couple of others, it seemed, had been drinking and gambling at Apoo’s house when a quarrel broke out. The reasons for the quarrel are not clear. The chisel of an educated imagination, however, might well crack the stony silence of the archival record.

It was, for instance, apparent from the testimonies that the victim was not a regular gambler and had not previously visited the vice dens of Entally. Perhaps Apoo had lured the young man he had befriended in Mauritius into joining the gambling table and lose his money. Fulia’s role too is unclear, though she was charged for the murder alongside Apoo. Might she have used her charms to persuade the dead man into sitting at the gambling table that night? Once he was at the table, the sequence of events is easier to surmise. As a novice, he would almost certainly have lost money. Given that he was drinking as well, he might well have lost a fair bit of money. Perhaps the lad realized too late that he had lost his money and feared how he would explain the loss to his father. His father had insisted that he knew every detail of his son’s movements till the night of the murder. Obviously, the gambling and the loss would have been difficult to hide from a father so observant of his son’s life. Probably fearing his father’s wrath, the youth demanded his money back. But Apoo was of course no ordinary layman. He was a vicious vice lord. He would have never agreed to the demand and had most likely tried to evict the dead man – which action perhaps had led to the fatal altercation. Apoo, we know from Khetra’s testimony, first threw a punch at the deceased before clobbering him with a sisoo-wood rolling pin and finally stabbing him. Khetra went on to describe how Apoo had murdered his erstwhile friend and then hidden the body in the lime-house on his property for a few days, before dumping it in the tank.

Clearly Apoo and his minions were operating beyond the law and with a recklessness that smacked of connivance with the law-keepers. Major Reveley certainly concluded that police corruption was a major part of the sordid saga. Vowing to clean up the force, he sacked the inspector who had been in charge of the case and demoted Superintendent Younan to the rank of a first-class inspector as well as suspending him for a period on disciplinary grounds. Finally, it seemed justice had prevailed.

But justice hardly dared to show her face in the shadowy underworld of colonial Calcutta’s gaslit streets. Despite the Major’s best efforts, the trial collapsed for lack of concrete evidence linking Apoo to the murder. The eyewitness testimonies were contradictory and the physical evidence, such as the bloody rolling pin the Major had recovered, inconclusive in the absence of the body. On 27th August 1867, Mr S. Wauchope, the presiding magistrate, acquitted both Apoo and Fulia for lack of definitive evidence. The notorious duo walked freely back to resume control of their empire of vice.

To add insult to injury, in the fall of 1868, Major Reveley retired from the force on health grounds and returned to England. Major Graham now took charge. One of his first tasks upon assuming office was to reinstate Mr Younan and the dismissed inspector. Apoo and Fulia had already returned to rule the shadows once more, but now their power was absolute. The bereaved father, after his brief moment in the archival spotlight, returned once more to mourn his dead son in obscurity. Perhaps he retired to the serenity of the temple of Kwan Ti in Dharmatala where a number of elderly Chinese men spent their twilight years in quiet contemplation.

Today Calcutta’s once thriving Chinese community has gradually dwindled. With them have gone the Indo-Portuguese, the Anglo-Indians, the Armenians, the Jews, and many others. Cramped and overcrowded streets have long replaced the airy gardens and serene ponds in Entally. Old men no longer bide their time at the temple of Kwan Ti. Gaslights too have long burnt out and been replaced by the harsh neon glares. Yet, crooked cops and underworld dons still daub the city; and gamblers of various hues keep rolling their myriad dice as the grabby Younans of our times keep turning a blind eye.

I wonder if, late on summer nights when the neon lights tire of their own harsh glow, a nameless young Chinese man, still redolent of his sun soaked days on faraway shores, might not still be roaming the streets of Calcutta in search of justice that he was denied. Or perhaps he is still cowering in the caliginous alleys of loss and filial shame, once again wagering his life for a better life.

Gevry interesting article sir.