It was the 30th of December 1879 and Caesar came home on the Star of Africa. Of course it wasn’t the ancient Roman monarch, Julius. It was an humble seacunny, Trazpero Caesar. Or was it Claspero? Some even called him Trisporong, or simply Proone. Names in the gaslit by-lanes of Calcutta flickered as much as the streetlights. Whatever his name, he must have felt himself to be no less than the Emperor Julius on that day. He had successfully navigated the treacherous sea route from Calcutta to Cape Town and back on his rickety Star of Africa. Finally, after months of toil and uncertainty, he was home. At last he could be together with his beloved, newly married wife, Regina, whom he had left behind. It was five months ago in August 1879 that Caesar had set sail. Throughout those long months at sea he had pined to be home and together with Regina once more.

Caesar was originally from Manila. He was among the many Lusophone seafarers who had sailed along the coasts of the Indian Ocean for centuries. In their names, looks, languages, religions, and métiers they kept alive the histories of the era before the rise of Pax Britannica when the Portuguese had dominated the Asian seas. Roman Catholic communities that spoke various Portuguese pidgins had developed all along the Indian Ocean sea routes. Cape Town, Mombasa, Colombo, Hughli, Pegu, Manila, Malacca, and Macau were like so many beads on a maritime rosary. The decline of Iberian sea power and the ascendance of the British Raj, however, had shuffled the deck of coastal opportunities. As the capital of the mighty new power, Calcutta, came to offer way more opportunities than some of the older ports like Malacca and Manila, the young Caesar decided to move to Calcutta.

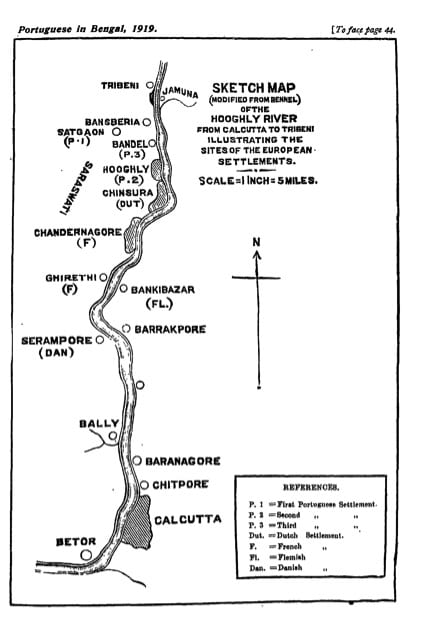

Early Portuguese settlements along the Hughli. [Source: JJA Campos, History of the Portuguese in Bengal]

As a seacunny, that is, a helmsman, Caesar had no dearth of opportunities in the booming maritime world of Calcutta. Soon after settling into the city, he had met and married the love of his life, Regina. They had been introduced by Santiago and it was Santiago who sponsored their wedding a while later. The thirty-year old Caesar was as happy as he had ever been and eagerly looking ahead to a life of professional and domestic bliss.

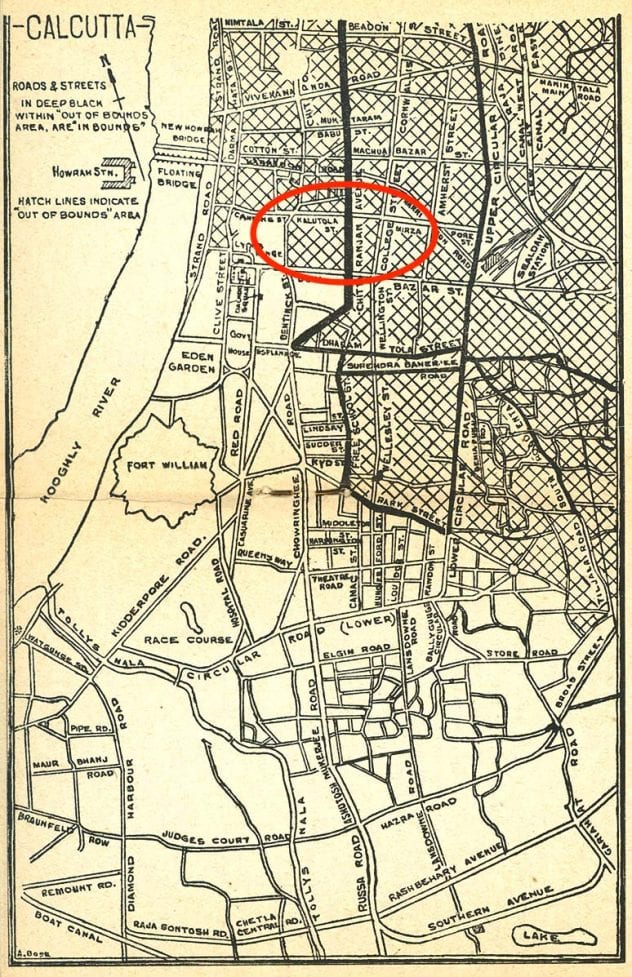

The young couple began their life together at 275, Brindaban Mullik’s Lane. Like many others of their class, Caesar and Regina rented rooms in a large boarding house. There were seventeen or eighteen rooms in the house and several tenants lived there. The landlady, Mrs. Jane Marian Carvelho, also lived at the house, as did the young, Nicholas Gomez, an out-of-work compositor who was Mrs. Carvelho’s nephew. Mrs. Sabina Rozario, Mrs. Carvelho’s sister, also lived nearby and spent much of her time with her sister. Brindaban Mullik’s Lane was only a stone’s throw from D’Cruz’s house in Champatollah and so the Caesars kept close contact with old Santiago as well.

Caesar had felt safe leaving Regina amongst all these people. He arranged for the landlady to pay his wife Rs. 10/- per month as well as giving her food and board till he returned from Cape Town and settled the accounts. The new couple was besotted with each other and Caesar had despaired at having to go to sea and leave his wife. Eventually he had left by consoling himself that he would soon be back. As he rushed from his vessel at the port to his rooms on Brindaban Mullik’s Lane bearing, one imagines, little gifts he must have brought back, he perhaps mused of how happy Regina would be to see him back in time for New Year. Peering through the haze beyond the glow of gaslights, we can almost see him smiling to himself at the thought of surprising his dear wife as he hurried along the busy streets of the mighty city.

But alas! His sweet reunion was not to be. Upon returning home, he found his rooms locked. On enquiring of Mrs. Carvalho, he learnt that while Caesar was at sea, the beautiful Regina had fallen in love with another man, a Bengali lad called Roger Le Roy, and moved in with him. She had even taken the little jewelry Caesar had bought her. As if to make matters worse, he learnt that he had only missed her by a couple of days.Stunned and confused, Caesar returned to his ship rather than spend the night alone in his rooms. There, amidst his shipmates, he drank himself to oblivion. He awoke the following morning with the usual urgency that follows a night of heavy drinking, perhaps with a sense of guilt at having wasted the previous day. Accompanied by four of his shipmates, he returned to his digs early on the morning of the 31st of December 1879. More focused and agitated than he had been the day before, Caesar demanded to know Regina’s whereabouts. Mrs. Carvelho and others informed him that Robert Le Roy and Regina were living at a rented accommodation on the nearby Baitakkhana Street. No sooner had he learnt this that he and his friends stomped off to look for Regina. But finding the couple proved difficult. Either because they were deliberately trying to avoid Caesar or because they were simply out enjoying the New Year’s Eve celebrations, Caesar and his friends failed to meet Regina despite trying for the better part of the day. Disappointed and at a loss once again, he returned home and slept alone in his room that night.

It must have seemed especially cruel that even as everyone else welcomed the new year, that night he, after months away at sea, had to lie alone in a dark room. The sound of people celebrating outside would have mocked his loneliness. Perhaps, he did not sleep at all, but lay awake all night trying to decide upon a course of action. His was not the usual fickle love of seafaring men. He was still as much in love with Regina as he had been when they first met and he pined to see her once more.

On New Year’s Day he rose early. Once more he located his four friends and once more they descended upon Baitakkhana Street to search for Regina and Robert. All morning the five friends scoured the area. Once more, they failed to meet the couple. But they did learn a lot about how the relationship had developed in his absence. How much of this was gossip and how much a true history of events is anyone’s guess. But by the time Caesar returned home that afternoon he seemed sullen and morose.

He remained alone and locked in his room till sundown. Around 6pm he got up and went directly to see Santiago D’Cruz. But since the latter was not home, his mistress offered Caesar a cup of tea. He accepted the tea and chatted with her politely for a while before asking to borrow some money from her. Since he was known to be close to Santiago, his mistress gave Caesar the money he wanted. Having thus obtained the money, Caesar tried to drown his sorrows in the almighty bottle. It seems highly likely that at the tavern he picked up more gossip and some news about Regina. Precisely what he heard has long been drowned in the cacophony of that rambunctious tavern, but around 8.30pm Caesar stormed out of the drinking hole with a new sense of purpose.

Returning home, he found Mrs. Carvelho and her sister Mrs. Rozario sitting in the courtyard chatting with two other tenants, Mrs. Lavinia Francis and Mrs. Virginian Silbrio, who was also called Virginia Stewart. Wordlessly, Caesar walked up to Mrs. Carvelho and stabbed her in the chest with a large knife. Mrs. Rozario tried to stop him and he stabbed her too. A stunned Mrs. Francis tried to intervene and fell back with multiple vicious stab wounds. Hearing the ladies shriek, Mrs. Carvelho’s nephew, Nicholas Gomez now came running into the courtyard. On trying to stop the spurned lover however, Nicholas too received a knife wound on his head. Scared for his life and bleeding, Nicholas ran out trying to find a beat constable. In the meanwhile, Caesar sought out Mrs. Stewart in her room and stabbed her there.

By the time Nicholas returned with the police, Caesar had left the premises. Of the four women, Mrs. Carvelho and Mrs. Francis were already dead and Mrs. Rozario and Mrs. Stewart were sinking fast. The viciousness of the attacks can be gauged by the fact that Caesar had stabbed Mrs. Stewart right in the center of her forehead and the knife went straight through her skull. The police and neighbors removed the two surviving women to the Calcutta Medical College as soon as they could. But both expired later that night.

In the meantime, Caesar turned up at Santiago D’Cruz’s home and called his godfather from the courtyard. D’Cruz’s tenants, Alice and Grace Browne, heard Santiago go out into the courtyard and within minutes heard him cry out in pain. Upon looking out they saw Santiago collapsed on the ground and bleeding profusely. He too had been stabbed.

The local police launched a massive manhunt for the absconding assassin, while a Magistrate, Mr. Gupta, accompanied by a Portuguese interpreter, Joseph Smith, took down the witness statements of the two women on their deathbeds at the Calcutta Medical College. In the shadowy by-lanes of central Calcutta, finding a man was not easy. Sailors were particularly difficult to track down. Despite trying all night, the police were unable to find the Caesar. A warrant had been issued for the dangerous murderer but few entertained any hopes that he would be apprehended. Most assumed that he had probably made his getaway on one of the numerous ships constantly leaving the port of Calcutta.

On the morning of the 2nd of January however, Trazpero Caesar, now the feared murderer of five people, walked nonchalantly into the local Lal Bazar Police Station. It was too early in the morning and the officers were still away. The Station was left under the charge of Prasad Singh, a Head Constable. Singh was alarmed to see the dreaded mass murderer walk in. But to his relief, not only did the man make no trouble, he meekly surrendered himself and confessed to the five murders. The police could hardly believe their luck. They quickly arrested him and put him on trial at the Magistrate’s Court within a week.

At the trial, the prosecution presented a compelling case. Mr. Hume, the prosecuting council, called upon a string of witnesses. Mr. MacKenzie, the police surgeon gave a detailed account of the injuries of each of the victims, before various eyewitnesses told the court how they had seen the murderer attack various victims. Nicholas Gomez delivered the most moving testimony as he spoke of his own plight as well as his efforts to save his aunt. Gomez also emphasized that Caesar was quite sober when he struck his victims.

After Gomez’s evidence, Caesar was asked if he wished to challenge any part of what Gomez had said. But Caesar disarmingly said, “What will I ask the witness? He has spoken the truth”.

Caesar offered no defense for himself. He readily and repeatedly confessed to the murders. But he did give a rationale for why he chose the victims he chose. He was sorry for having attacked Mrs. Francis and Mrs. Rozario. He stated that he was forced to do this because they had intervened in his attempts to kill the others. Regarding the other three victims however, he remained unrepentant. He said he had killed Mrs. Stewart for having given bad advice to his wife. Mrs. Carvelho was killed for having allegedly ‘witchcrafted’ Regina. And Santiago, according to Caesar, had himself had an affair with Regina while he was away. All three, in Caesar’s view, deserved the justice he had meted out to them.

Undoubtedly, the most striking of these allegations was that of witchcraft that Caesar leveled against Mrs. Carvelho. Interestingly, Luso-Asian women such as Mrs. Carvelho had long had a reputation for practicing various sorts of love-magic. The seventeenth-century English merchant, John Marshall, had reported on Luso-Bengali women practicing such magic to charm men. He said he had personally known individuals, especially Dutch merchants, who had been thus charmed. The Italian adventurer, Nicola Manucci, had similarly reported stories about a Cochinese woman named Lunna who was famous for her love magic. So widespread was Lunna’s fame that it was rumored that the great Mughal general, Mir Jumla, was among her clients. These allegations were often wrapped up in allegations of witchcraft. It is quite possible then that Mrs. Carvelho might already have had reputation for practicing some forms of love magic even before the sordid saga of Regina’s elopement. This would explain why Caesar believed whatever rumors or gossip he had chanced upon.

Precisely what motives Caesar thought Mrs. Carvelho may have had for bewitching Regina are more difficult to discern. Were there rumors about Robert Le Roy having paid her to put a spell on Regina? Or did he perhaps think that Mrs. Carvelho simply sought to avoid the additional expense she was incurring from having to provide bed and board to the lady by setting her up with a new man? Another possibility might be that Mrs. Carvelho already had some kind of a reputation as a procuress. It would not at all be unlikely for the landlady of a boarding house inhabited by poor, working class women to also double up as a madam.The allegations against Santiago are more predictable. As a relatively wealthy man of some influence within a small, overwhelmingly poor community, it would not have been difficult to imagine him taking sexual advantage of women in straitened circumstances. Naturally, for the women, especially the sailor’s wives left for months without money or certainty, these liaisons might have provided both a distraction and a way out of the griping poverty. It is possible that such rumors about Santiago were already floating around at local taverns even before Regina’s name came up.

However plausible, what finally made the allegations real enough for Caesar to trigger such vicious slaughters was the depth of his love for his wife. Not once did he blame her for her actions. He saw her as someone who had been manipulated and even preyed on by others. He reiterated to the court – “I am guilty of all the crimes. I do not wish to say anything or be asked anything. I only want to see my wife”.

Edifying as his love might have been, it did not sway the jury and they found him guilty of culpable homicide amounting to murder for all five victims.

Since it was a murder trial, the guilty verdict at the magistrate’s court sent the case to the High Court. There, the court appointed Alexander Souttar as a public defender, while Mr. Bell was the prosecutor. Mr. Souttar convinced Caesar to plead ‘not guilty’ and attempted to convince the jury that the murders were committed in the wake of sudden and extreme provocation. Mr. Bell however, pointed out that the outrage was of “more than ordinary tragic nature” and that the jury had an obligation to put an end to such “frightful crimes” in the interest of “public welfare”. The jury went along with Mr. Bell and found Caesar guilty once more. The Hon’ble Mr. Justice Broughton, who presided over the trial at the High Court, followed the guilty verdict by sentencing Caesar to be hanged to death. The unhappy lover was thus executed on the 9th of February 1880.

Unfortunately, no record survives as to whether his ardent wish to see Regina one last time had been fulfilled before he died.

Excellent!

Thanks, Rajat.