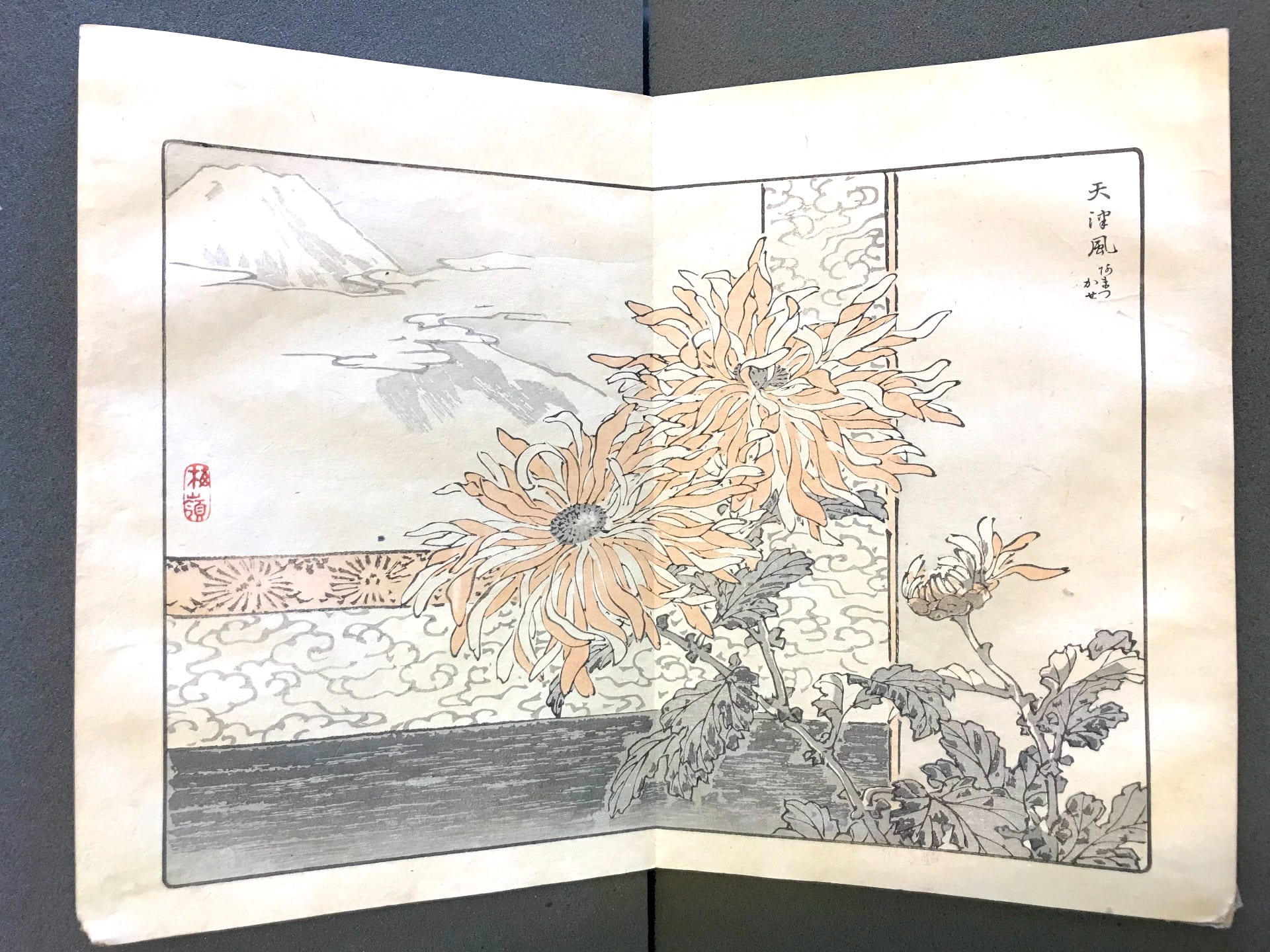

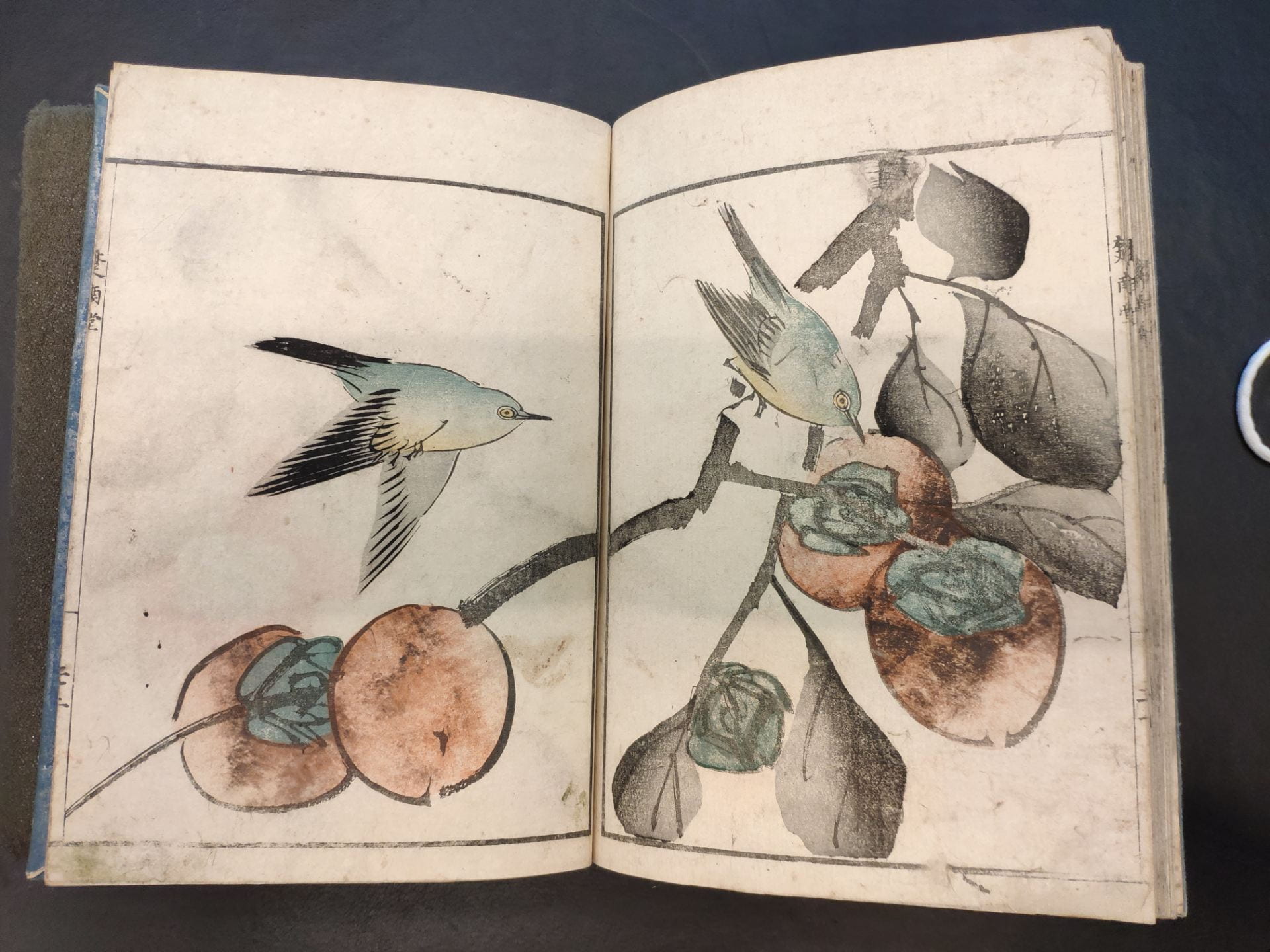

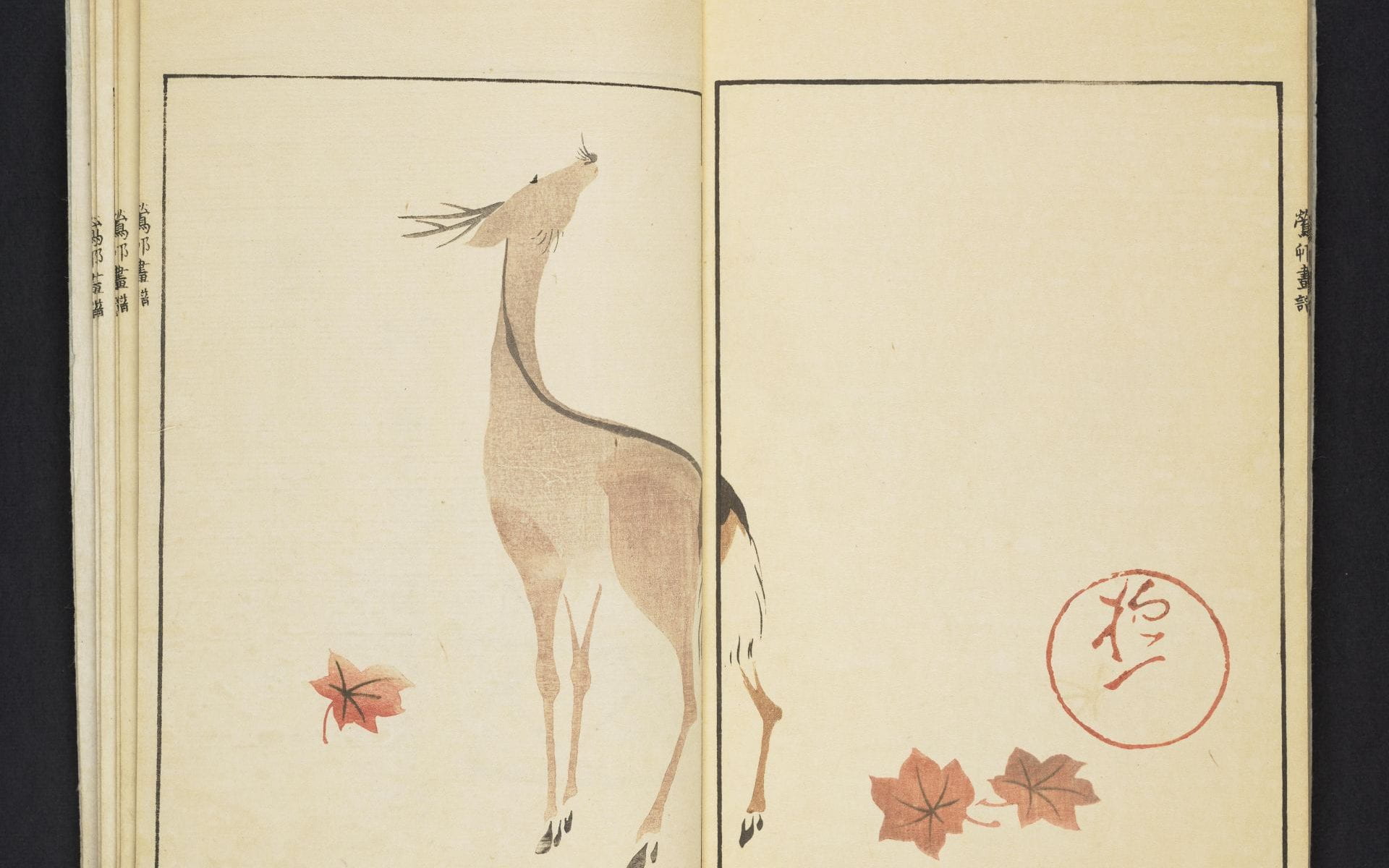

Artist: Kōno Bairei 幸野楳嶺 (1841 – 1895)

Title: Bairei kiku hyakushu 梅嶺菊百種

Date: Vol. 1: 1891 (Meiji 24); Vol. 2: 1892 (Meiji 25); Vol.3: 1896 (Meiji 29)

Medium: Woodblock printed; ink and color on paper

Publisher: Ōkura Magobē 大倉孫兵衛 (1843 – 1921)

Donor: Presented by Arthur Tress. Arthur Tress Collection, Box 11, Item 2 (Volumes 1 and 3); Box 23, Item 9 (Volume 2). https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977502562303681 https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977502745103681

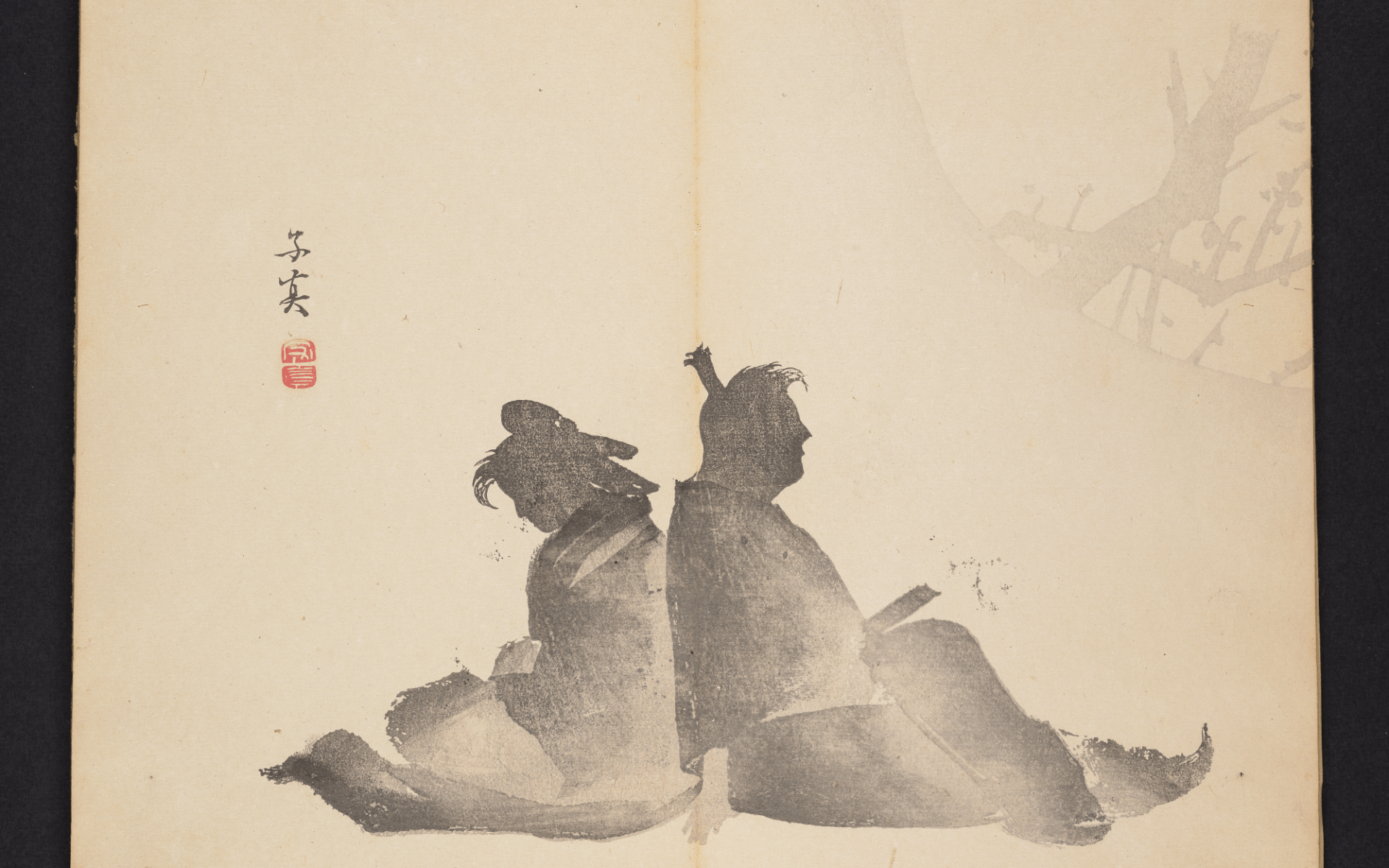

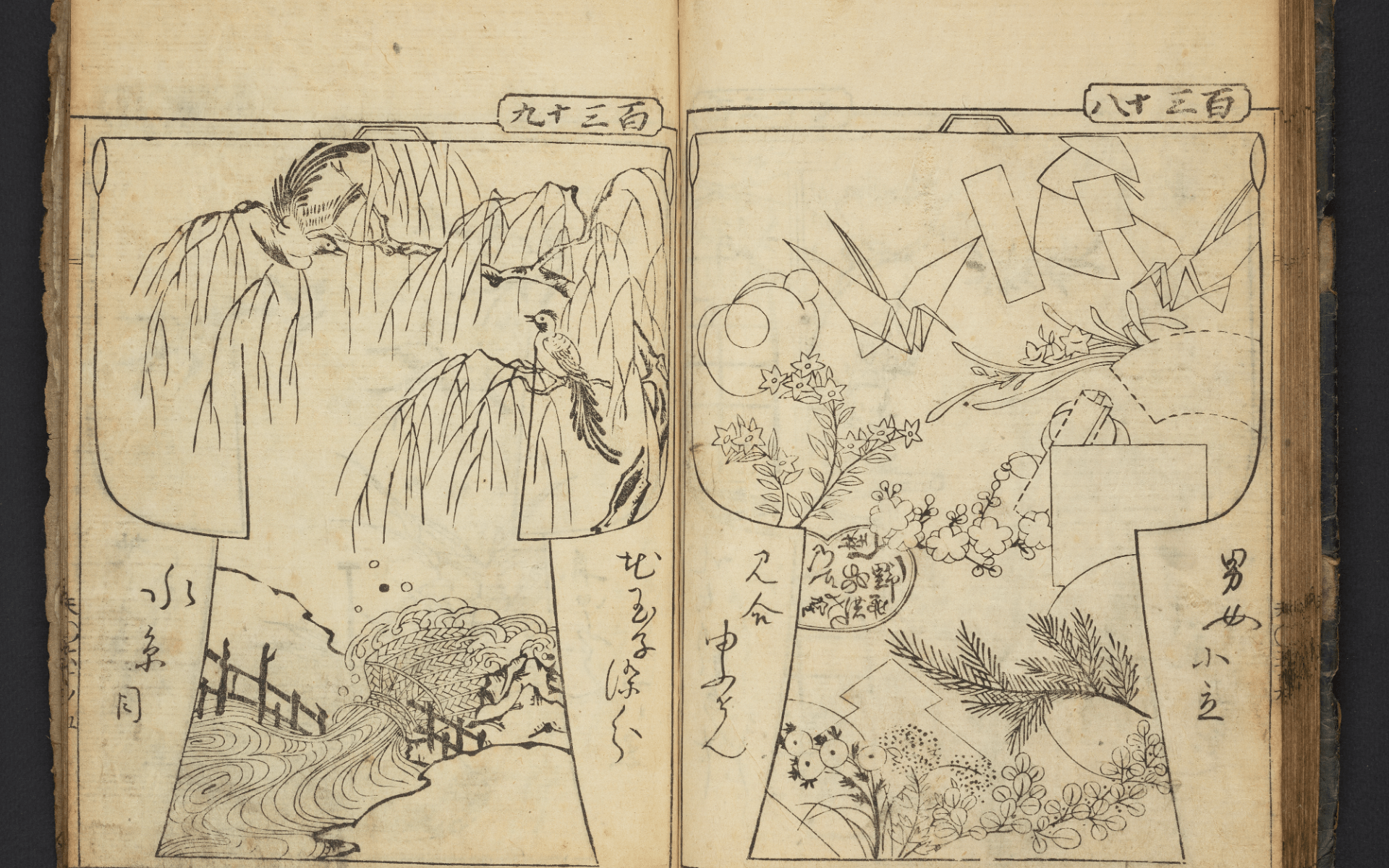

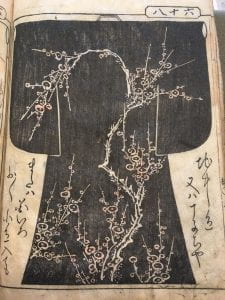

Bairei kiku hyakushu 梅嶺菊百種 “Bairei’s One Hundred Varieties of Chrysanthemum’ is a three volume set designed by the artist Kōno Bairei. The volumes contain delicately printed chrysanthemum flowers framed in different contexts — from wild chrysanthemums blown awry by the wind, to dainty ones in the company of birds and insects. Each print is inscribed with the artist’s seal.

Kōno Bairei began his training at the age of eight with Nakajima Raishō (1796-1871), a Maruyama school artist, and later with Shiokawa Bunrin (1808-1877) of the Shijō school. He was well-known in the Meiji period for his ukiyo-e prints and paid special attention to pictures of birds and flowers (kachō-e). His pictures displayed a keen engagement with western realism and thus had a market in the West as well. In addition to his artistic prowess, Bairei is also known for his role in developing art education. Along with others such as Kubota Beisen (1852-1906) and Mochizuki Gyokusen (1834-1913), he established the Kyoto Prefectural Painting School in 1878. In 1886, he co-founded the Kyoto Young Painters Study Group with Kubota Beisen, with whom he also began the Kyoto Art Association in 1895.

The images displayed here are from volumes 1 and 3. The image on the right, from volume 3, is bursting with movement, heightened by the petals made wild by the wind. On the left, from volume 1, is a beautiful print presenting the iconic Mt. Fuji as a backdrop to Bairei’s chrysanthemums.

Other copies: Pulverer Collection, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington DC; British Museum, London; Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Selected Readings:

Hillier, Jack, The Art of the Japanese Book. London: Published for Sotheby’s Publications by Philip Wilson Publishers, New York, 1987, p.959-74.

Posted by Ayesha Sheth, Fall semester, 2019