Being surprised is one of the great pleasures of historical research. As little as a passing reference in a single document can spark new understandings of a person, event, or era. In 2019, I began research on a book project about the long aftermath of the Louisiana Purchase and the United States’ century-long project of colonizing the vast lands it had ostensibly acquired from France in 1803. Early on, I turned to The Territorial Papers of the United States, a collection mostly composed of government documents published in twenty-eight volumes between 1934 and 1975.1 As I dug in, I thought these papers would provide a solid introduction to U.S. state-building and colonialism but offer few revelations. I also anticipated that the story would begin in earnest in the winter of 1803-1804, after U.S., French, and Spanish officials in New Orleans and St. Louis conducted the transfer ceremonies that formally ceded the colony to the United States. I soon learned that I was wrong on both counts.

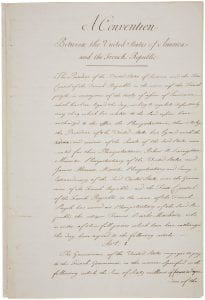

The diplomacy leading to the Louisiana Purchase is one of the best-known events in U.S. history. Scholars have extensively documented western Americans’ demands for access to the Mississippi River, Spain’s geopolitical strategy in the region, and negotiations between the United States and France that led to Napoleon selling Louisiana. In popular books, documentaries, and periodicals, authors frequently call the Louisiana Purchase “the greatest land deal” in the history of the United States, North America, or the world, depending on their audacity.2 Yet, in many respects, the most significant aspects of the Louisiana Purchase began, not concluded, when U.S. and French diplomats signed the treaty in April 1803.

Over the last two decades, a growing number of historians have underscored the complex implementation of the Louisiana Purchase treaty. Scholars focused on what is now the state of Louisiana have emphasized the ongoing negotiations that took place between U.S. officials, American settlers, and Francophone communities.3 Others have noted that, while the Louisiana Purchase treaty culminated one round of diplomacy, it initiated another decades-long process in which the United States negotiated and coerced land cessions from Indigenous nations. Taking those subsequent treaties into account, the purchase price for Louisiana balloons from the oft-quoted figure of $15 million to upwards of $2 billion.4

In my first book, Masters of the Middle Waters: Indian Nations and Colonial Ambitions along the Mississippi, I examined centuries of colonialism in the central Mississippi River valley, concluding in the 1820s as the United States solidified its authority over the region. Yet, I still had unanswered questions about the mechanisms of U.S. imperialism and on-the-ground interactions between U.S. officials, Native peoples, and anglophone and francophone civilians. Under the treaty with France, the United States claimed more than 800,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River, but it would not colonize much of that territory for decades. How exactly did that process unfold? This question sent me to The Territorial Papers, which soon revealed that even the initial enactment of the treaty was more convoluted than I had expected.5

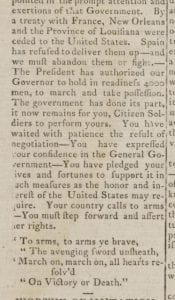

These reports whetted my curiosity. I knew that raising a force of 6,500 troops would have been a substantial undertaking for those three states. After all, in 1803, the entire U.S. Army numbered only about half that many soldiers. I was left with many questions. How far had the states taken these preparations? How did they recruit these volunteers? Beyond the 500 Tennesseans, did any of these men go into the field? To find answers, I had to venture far beyond The Territorial Papers. I examined records from the War Department, official correspondence between the Jefferson administration and state governors, the papers of politicians in the three states, and newspaper accounts. These sources revealed a broad effort by members of the Jefferson administration, state governors and legislatures, and private citizens to recruit volunteers, and they also documented varying levels of success in each state. These undertakings both complicated the standard narrative about the months between the treaty and the transfers and also offered an opportunity to examine the U.S. federal system at work. My research in The Territorial Papers thus set me on a journey that led to my summer 2023 article in Early American Studies.

Although extensive, The Territorial Papers are not exhaustive. The editors of the volumes admitted as much. The records of territorial courts and legislatures were not included, nor were most papers related to either the military or Indian affairs.11 However, the breadth of topics discussed in these volumes makes them a good starting point for many projects, especially those concerned with the actions of the U.S. state. Despite their frequent use by generations of scholars, the documents in them still hold surprises.

Jacob F. Lee is Associate Professor of History at Pennsylvania State University. His first book, Masters of the Middle Waters: Indian Nations and Colonial Ambitions Along the Mississippi, won the Jon Gjerde Prize from the Midwestern History Association and a Best of Illinois History Award from the Illinois State Historical Society. He is currently writing a history of struggles surrounding legal jurisdiction and sovereignty in nineteenth-century Indian Territory.

Read Lee’s article “Do You Go to New Orleans?”: The Louisiana Purchase, Federalism, and the Contingencies of Empire in the Early U.S. Republic” in EAS’s Summer 2023 issue.

- Clarence Edwin Carter and John Porter Bloom, eds., The Territorial Papers of the United States, 28 vols. (Washington, DC: GPO, 1934-1975). ↩

- Based on newspaper evidence, this claim seems to have come into popular usage in 1903, as Americans commemorated the centennial of the Purchase. Since then, it has been widely repeated, sometimes among academics, but especially in non-scholarly venues. In 1997, filmmaker Ken Burns deemed the Purchase “the greatest land deal in history” both in a PBS documentary about Jefferson and in an accompanying article reprinted in scores of newspapers across the United States; Burns, Thomas Jefferson (Alexandria, VA: PBS Home Video, 1997), https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/thomas-jefferson; Burns, “What Jefferson Means Today,” USA Weekend, February 14-16, 1997, 5. For a recent use of this rhetoric, see Laurence S. Smith, Rivers of Power: How a Natural Force Raised Kingdoms, Destroyed Civilizations, and Shapes Our World (New York: Little, Brown Spark, 2020), 43. ↩

- Peter J. Kastor, The Nation’s Crucible: The Louisiana Purchase and the Creation of America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004); Julien Vernet, Strangers on Their Native Soil: Opposition to United States’ Governance in Louisiana’s Orleans Territory, 1803-1809 (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2013); Eberhard L. Faber, Building the Land of Dreams: New Orleans and the Transformation of Early America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015). ↩

- Robert Lee, “Accounting for Conquest: The Price of the Louisiana Purchase of Indian Country,” Journal of American History 103, no. 4 (2017): 921-942; Kent McNeil, “The Louisiana Purchase: Indian and American Sovereignty in the Missouri Watershed,” Western Historical Quarterly 50, no. 1 (2019): 17-42. ↩

- Clarence Edwin Carter and John Porter Bloom, eds., The Territorial Papers of the United States, 28 vols. (Washington, DC: GPO, 1934-1975). ↩

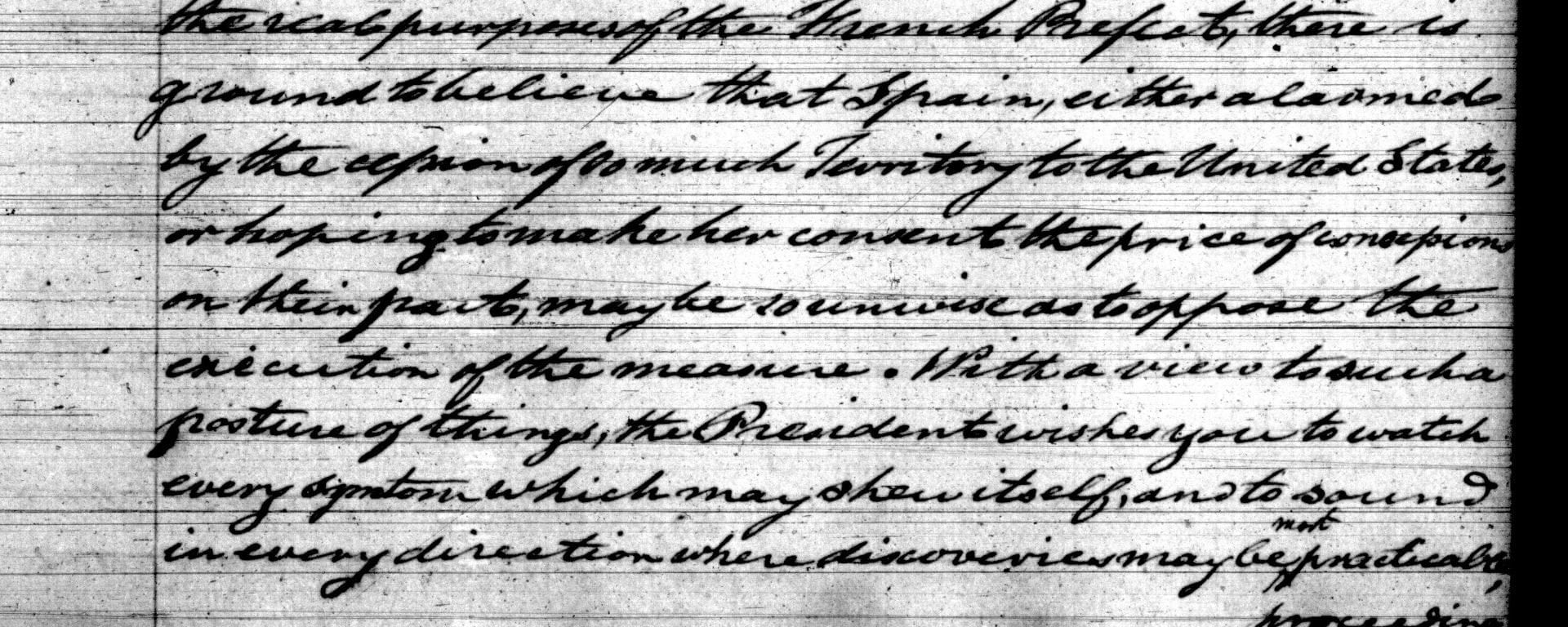

- James Madison to Daniel Clark, September 16, 1803, in TPUS, 9:55. ↩

- James Madison to W.C.C. Claiborne, October 31, 1803, in TPUS, 9:93. ↩

- Henry Dearborn to James Wilkinson, October 5, 1803, in TPUS, 9:71. ↩

- Henry Dearborn to James Wilkinson, October 31, 1803, in TPUS, 9:96. ↩

- W.C.C. Claiborne to Thomas Jefferson, December 8, 1803, in TPUS, 9:136. ↩

- TPUS, 9:iv-v. ↩