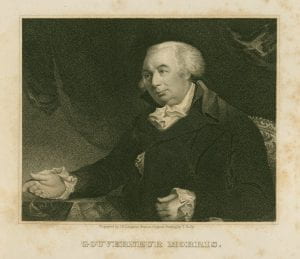

Prior to commencing my journey to a Ph.D., I spent a semester in 2013 studying history at MIT with the remarkable Pauline Maier. While discussing my doctoral project centered on Gouverneur Morris, her audible gasp punctuated our conversation, “Ah! The Gouv!” She then quipped: “Well, it will be a good thing to have a French perspective on Morris’s affairs in France.” It marked the first time I was pleasantly reminded of my French background while delving into American history. As the ramifications of nation-building extend to global connections in the present-day, it is legitimate to wonder what we, as French scholars, bring to the study of the American Revolution.

Epistemological Biases

The American Revolution and the Early Republic have long interested the French. From the moment Louis XVI’s government recognized the substantial opportunities the American Revolution presented for retaliating against their longstanding British adversary, they forged ties with the Americans that they solidified in the military, economic, and diplomatic realms.

Later, these connections deepened, extending into both ideological and cultural spheres. Figures such as the Marquis de Lafayette, François Alexandre Frédéric, duc de La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, and, notably, Alexis de Tocqueville, were all fascinated – albeit differently – by the emerging American spirit, the nation’s burgeoning civilization, and its unique political culture.

However, because the French underwent their own political transformation beginning in 1789, observers of French history couldn’t help but juxtapose the American Revolution against their own revolutionary experience. This comparison served to diminish the American Revolution, which some viewed as not a true revolution, or to align it with the events of 1789 as sister revolutions. Additionally, those interested in tracing the influence of the French Enlightenment also asserted French superiority in terms of revolutionary ideology and expertise.

As French historians penned analyses of the French Revolution, they naturally came to think of the American Revolution as its foil. An early peculiarity among French scholars was their inclination to view the American War of Independence as not just a domestic affair but as an international event. Yet, they also always saw it as less significant than the French Revolution whose exceptionalism fueled their desire to uphold French political grandeur (see the works of Jules Michelet as an example). The American Revolution was indeed a watershed in the history of European (de)colonization, but with France and Great Britain as its main characters.

Globalized Perspectives

In the 1950s, the advent of the Cold War and the ideological standoff between the eastern and western blocs inspired a new school of thought: Atlantic history, spearheaded by scholars like R.R. Palmer and Jacques Godechot. Both American and French historians posited that the two revolutions were part of an interconnected Atlantic movement, emphasizing long-shared Western ideological roots.

From the 1970s onward, more and more French historians specialized in studying the American revolutionary era, contributing new perspectives to constitutional and cultural history (see, for example, the works of Richard Marienstras, Patrice Higonnet, Marianne Debouzy, Serge Ricard, Pierre Mélandri). They questioned the meaning of the American Revolution by exploring individual narratives, whether from the bottom up or top down, with an initial focus on the Framers and later on Huguenots, women, enslaved Blacks, and Native Americans.

To French historians today, investigating the American Revolution is no longer a means to assert the superiority of the French Revolution. Instead, it is a way to scrutinize broader patterns of political, economic, or gendered domination, and to question established paradigms and analyze the complex interplay of this transformative era.

The Language Barrier

Nevertheless, there remains one major obstacle to cross-pollinating scholarship on the American Revolution: many French-language monographs can’t reach an American audience. Consequently, Francophone historians find limited traction on the American stage, even though their work in French sources brings novelty to the field.

Reflecting on my personal experience, my in-depth study of Gouverneur Morris, written in French, still needs to be translated and adapted into English for broader accessibility to an anglophone readership, even though I have published a few articles in English. Nonetheless, the quantity of French sources I consulted for my study adds new dimensions to the conversation on Morris and the Atlantic Revolutions.

To suggest a definitive answer to the question; “What do we, French historians, bring to the conversation that is different from the perspective offered by historians from the United States?” would be presumptuous. However, by overcoming the language barrier (as shown by Greg Robinson in a 2015 article pointing out the absurdly tiny number of reviews for French-language books on American history)1, we could open our research to an English-speaking audience and demonstrate the new, interdisciplinary, and multifaceted interpretations that French historians bring to the study of this event that stem from the specificities of our French academic training and historiographical tradition.

Author’s Note:

I use the term ”French scholars” as a general label to encompass Américanistes with a formation in history, and Américanistes with a civilisationniste background: the former work in history departments and the latter are affiliated with anglophone studies.

Emilie Mitran received her Ph.D. in American and French history in 2019 from Aix-Marseille University. She published a monograph in 2022 (Gouverneur Morris, traducteur de la Révolution française, Rennes: Les Perséides) and currently teaches at the University of Toulon.

Read Mitran’s article “Gouverneur Morris, France, and Republicanism in the Atlantic Space” in EAS’s Winter 2024 issue.

- In the American Historical Review, I found 21 book reviews over the century between 1905 and 2008, including one in the 2000s, four in the 1990s, and two or three in most other decades. https://www.historians.org/research-and-publications/perspectives-on-history/march-2015/francophone-historians-of-the-united-states ↩