What Does PZ Myers Despise?

A quick followup to my remarks in the previous post… PZ Myers despises something. It turns out that the panel discussion I recently mentioned has been transcribed, and according to the transcript (from which I take all quotations), Myers says:

I’m interested in evolutionary problems, and that’s how evolutionary psychology came to my attention. I’ll just say ahead of time: My bias is, I despise it.

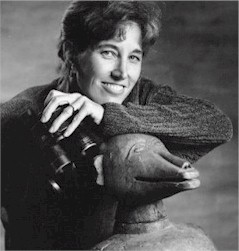

Despise…He doesn’t disagree with it, or take issue with its findings. His objection is visceral. Reading the transcript and his remarks elsewhere, however, it’s fairly clear he does not, really, hate evolutionary psychology. He hates what he thinks evolutionary psychology is. Actually, there’s evidence he likes the field. Take, for instance, his view of Sara Hrdy’s work. Hrdy has played an active role as an officer in the Human Behavior and Evolution Society (HBES) and was recently awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award by this group, which is arguably the world’s leading collection of evolutionary psychologists. Wikipedia calls Hrdy “an American anthropologist and primatologist who has made several major contributions to evolutionary psychology and sociobiology.” (That’s Wikipedia, not me, placing her in these categories.) Indeed, here she is in this picture taken at the recent HBES conference – organized by Deb Lieberman and Mike McCullough – smiling next to Doug Kenrick, Leda Cosmides, and Steven Pinker, among others. If she’s not at the epicenter of evolutionary psychology, it’s hard to know who is. Of Hrdy, Myers gushes:

… people like Sarah Blaffer Hrdy who does a lot of cultural anthropology. I think it’s phenomenal stuff.

(Greg Laden, also on the panel, similarly holds up a central member of the community as an example of good work in the field, Dan Fessler, former co-editor-in-chief of Evolution and Human Behavior. Laden says: “There’s actually some good studies, some good evolutionary psychology studies that people who claim it help [inaudible] have done. Just go to the UCLA department of anthropology and look at Dan Fessler and Boyd and so on…”)

So if Myers loves Hrdy, who does he despise? In the transcript, Myers explicitly discusses an example. He is, I’m fairly certain, referring to this paper by Morton et al. in PLoS Computaional Biology (“Mate Choice and the Origin of Menopause”) when he says:

This is a common theme in many of these popular evolutionary psychology articles too, is that women are the passive recipients of the male genetic heritage. There was this recent thing. Maybe you’ve heard about the menopause study?

This paper wasn’t, however, written by evolutionary psychologists or anthropologists, but rather the good guys in Myers’ world view: biologists (at McMaster, in this case). The paper did not appear in one of the field’s journals, but rather in PLoS. I don’t have a particular view about the work, and I suppose by some stretch it could count as evolutionary psychology, but only by a stretch, and the work seems far more distant from the center of the discipline than, say, Hrdy’s work.

Myers, then, is a bit like the Dave Chapelle character Clayton Bigsby, the Black White Supremacist. In this (salty, NSFW) sketch (note, some might find this sketch offensive), Bigsby plays a blind black man who, not knowing he’s black, becomes a leader of the White Supremacist movement. Like Myers, he’s filled with a lot of rage, but doesn’t really know who or what he hates. Myers thinks he hates evolutionary psychology, but when he gets specific, he loves people at the center of the field, and hates papers that lie outside of it.

You can see this as well by his other remarks. As Pinker mentioned in his replies to Myers’ comments, Myers seems to despise spatial modularity. Myers (incorrectly) thinks that evolutionary psychology is committed to the idea that different functions of the mind are spatially localized. He thinks this is what we mean by “modularity.” (I’m partial to this paper on modularity, for obvious reasons.) Myers says:

I read one paper by an evolutionary psychologist that was trying to pin down this idea of the modules in the brain. Okay, they were going to show us that there actually are these modules in the brain. And the one they found was the amygdala.

According to the transcript, this was followed by [audience laughter] and then:

Okay, now maybe you don’t know, but the amygdala is everywhere. Fish have an amygdala. So how can you justify saying that this is a site for a specific adaptation for human beings when it’s something so universal.

From this, it’s clear that Myers doesn’t understand the way the term “modularity” is used in evolutionary psychology. The fact that he thinks that the fact that “the amygdala is everywhere” is relevant to this discussion is startling. (I should say for the record I have no idea what “paper by an evolutionary psychologist” he’s talking about. If anyone knows, I will be pleased to add a note here and link to it. For the record, I’m guessing that the paper in question was not, in fact, written by someone who self-identifies as an evolutionary psychologist and that the paper did not, in fact, appear in one of the field’s journals.) The point is that by referring to “a site for a specific adaptation” he reveals, again, that whatever it is that he despises, it’s not evolutionary psychology. (He also says: “You know, there is not a coloring-in-the-lines module in the brain. There is not a module that says you like broccoli, right? It’s much more complicated.” I concede these statements are all true – especially that it’s complicated – but of course these are non-sequiturs, given that no one has made any such claims.) Another panelist, cognitive neuroscientist Indre Viskontas said: “if you’re trying to say that the brain is modular and this region does that. Well, it totally depends!” reinforcing the idea that the confusion regarding modularity was not limited to Myers on the panel.

Another thing the panel apparently doesn’t like about evolutionary psychology is the EEA concept – the environment of evolutionary adaptedness – which I’ve discussed before. Greg Laden, another panelist, breaking tradition, identified a source for a claim about the field, writing:

…in the original Adapted Mind, the book that put out the first papers on evolutionary psychology, there is actually an article explicitly stating the EEA concept as being the savannah of the Serengeti. It says this is the environment in which people like the bushmen would have been living for two million years. And the paper explored our interest in bonsai trees and certain other landscaping things.

From the last sentence, it’s clear he’s referring to the chapter by Orians and Heerwagen, “Evolved Responses to Landscapes.” While it’s true that they wrote: “The savannas of tropical Africa, the presumed site of human origins…” but, and I can’t stress this enough, the “presumed site of human origins” is not the same as the EEA concept. Like modularity, the EEA concept is a technical term, and has been laid out in such exquisite detail – including in the Psychological Foundations of Culture chapter in the book Laden refers to — it really is striking that critics of the field still manage to get this wrong. Indeed, the abbreviation EEA doesn’t appear in the Orians and Heerwagen chapter (according to my Amazon and Google searches inside the book). (I tried to help Laden out on this issue back in December of last year.)

Myers also objects to what he takes the field to be because he seems to think that the discipline endorses genetic determinism. From his remarks, it’s clear that Myers is stuck in the old dichotomies, especially genetic as opposed to flexible. He says: “It’s got to be plastic. I don’t think it’s genetic.” Because he takes the field to be saying that behavior is fixed/genetic/inflexible, he thinks the field is wrong because the brain is plastic/flexible. Related, he also said: “There isn’t a one-to-one mapping of genes to behaviors, but they assume it is. They always argue that it is.” Since we always argue this, Myers should be able to document this claim easily, but of course he can’t, because it’s just not true.

While most of what Myers takes evolutionary psychology to be is wrong, partially explaining his hostility, I concede that there could be points of genuine disagreement. First, Myers said: “if you’re doing evolutionary biology, I expect you to look at the genes, okay?” This is a genuine difference. Because evolutionary psychologists focus on hypotheses regarding function, the evidence is typically design evidence, following the logic laid out by George Williams. Indeed, many of us think that there was plenty of good evolutionary biology being done before anyone knew that genes existed. Charles Darwin, for instance, managed pretty well. Myers’ insistence on genes when studying behavior, however, doesn’t really set him up against evolutionary psychology so much as animal behavior and behavioral ecology more broadly. As I and others have pointed out, inferring function from form – morphology or behavior – is business as usual in animal behavior. Insisting on genetic evidence, then, isn’t a complaint specific to evolutionary psychology. (This difference in views might help to explain the expanding Coyne/Myers debate.) Denying that one can infer a trait’s function from its form puts one out of step with the mainstream biological community, as I’ve discussed before, using Futuyama’s textbook as evidence.

And, just for completeness, I should say I have no real idea what to make of these remarks:

…when you actually find evolutionary psychologists who are willing to talk about the real data and get down to the basics, they can’t point to anything that’s unique to humans in the last 10,000 years. They have to go to things like the amygdala or breastfeeding. You know, that’s a mammalian characteristic. We’ve got 80 million years of that to discuss. It means that the stuff they’re talking about, the very specific stuff that they’re testing on college students, they don’t have genetic or biological evidence for any kind of difference.

By the way, of the several hundred people at HBES who were “willing to talk about the real data,” exactly one mentioned the word amygdala, and two mentioned breastfeeding. Anyway, Amanda Marcotte, who I’ve discussed before was also on the panel. She said:

I often, very frequently, get requests to debate an evolutionary psychologist in a public forum, and I always decline and offer to refer them to a biologist who is willing to debate them. And they always take a pass. And I think that’s very telling–that they want to debate a journalist, somebody with no PhD, no science background, who likes science but doesn’t really understand it to the same extent that the rest of the people on this panel do.

I’m a bit surprised that she has “very frequently” been asked to debate evolutionary psychologists. This forum would have been a perfect opportunity, yet the organizers chose not to invite a single evolutionary psychologist. Out of curiosity, readers, have any of you, ever, “taken a pass” at debating a biologist?

Anyway, to return to Myers, he closes with this:

There is a sound basis, a material, biological basis to how the brain works, and I agree 100% with that. And I will say that even I am doing research on genes and behavior in my lab, but I do it on fish, where you can do real experiments. Come on.

Aw, just, just come on… Anyway, to pick up on Hugo Mercier’s comments in my prior post, it’s probably true that there are better labels than the one I chose to use. Are there good terms to use to refer to people who are evolutionary psychologists in at least some sense but (think that they bitterly) disagree with parts of the enterprise?

Is Debating Creationists of the Mind Worthwhile?

Readers occasionally ask me why I don’t write about creationism, as some prominent evolution-minded bloggers do. To me, the benefits of discussing creationism is limited because my sense is that on this issue, there is little room for persuasion and therefore little value to continued discussion. People who adopt supernatural beliefs, it seems to me, tend to adopt them for reasons other than their evaluation of the relevant evidence and logic, so presenting evidence and logic has limited persuasive value. This debate really ended a century ago, when the Enlightenment teed up supernaturalism and Darwin spiked it. The discussion is, to my mind, over, and dissenters are simply history’s stragglers less interested in discovering truth than defending a worldview. Why bother fighting?

I suppose that things aren’t, really, as absolute as I’ve presented it here. Occasionally students tell me that taking my evolutionary psychology class changed their minds – or at least made them think about changing their minds – about their prior religious commitments. Still, my sense is that readers of this blog are unlikely to be creationists to begin with, further limiting the value of sharing any thoughts I might have about the topic. So I don’t.

Recently, I discussed some remarks by PZ Myers, who might be called – though I’m sure he would object – a creationist of the mind. (This term isn’t original with me. Anyone know who coined it?) By this I refer to the view that the theory of evolution by natural selection ought to be used to inform the study of the traits and behaviors of every living thing on the planet except the bits of the human mind that cause behavior, especially social behavior. Again, I’m not saying he’s literally a creationist; I’m saying that there are some who are very comfortable insisting that evolutionary ideas inform biology in all other domains except the human mind. This view is not unprecedented. Ed Clint directed my attention to this quotation from Alfred Wallace:

Because man’s physical structure has been developed from an animal form by natural selection, it does not necessarily follow that his mental nature, even though developed pari passu with it, has been developed by the same causes only.

So, Myers and people like him are in distinguished company. In any case, on the heels of my prior post, the question was raised: why do I bother?

Fair enough. I concede there is some justice to this view. Is pointing out Myers’ errors any more useful than trying to persuade creationists? The rest of my remarks here are some thoughts on this question.

First, the con side. Like creationists full stop, creationists of the mind take their positions for reasons other than looking at the relevant evidence. This is clear from the emotion that pervades their remarks about the discipline and, more convincingly, from the way they characterize the discipline. As I’ve shown elsewhere, critics’ errors about the field show that they haven’t understood the most basic assumptions that underlie the field. For instance, the complaint that PZ Myers recently voiced, that evolutionary psychologists assume a one-to-one mapping between genes and behavior, sinks to the level of “pants-on-fire” along the veracity scale, and such moves are in essence parallel to the old canard, “if we evolved from apes, why are there still apes?” from certain creationist quarters. This misrepresentation, so at odds with reality, betokens a willful disregard of the facts of the matter, illustrating that resistance to the field comes from a source other than the ideas of the field itself. Genuine critics – Fodor I think provides such an example – engage the logic that underlies the discipline and the relevant empirical evidence. Given that creationists of the mind’s opposition comes from a source other than their evaluation of the field, there would seem to be little value in trying to persuade.

So goes the con side, and I take the point. If creationists of the mind cannot be convinced that there is value to using ideas from evolutionary biology in formulating hypotheses about human psychology, then why engage them when there are other ideas to write about?

Having thought about this from time to time, I came down on the pro side, but I’m willing to be convinced otherwise.

First, there is counter-evidence to the claim that critics cannot be persuaded: Jerry Coyne’s conversion I think serves as a powerful example. His journey from staunch critic to defender of the discipline illustrates that smart people who know a lot about biology can be persuaded. Some of the field’s critics might be induced to read the primary literature, as Coyne did. More deeply, Coyne’s public change of heart, I think, will make it easier for others to say they were wrong. Indeed, my sense of the comments on his blog illustrate the point. I haven’t studied the comments systematically, but I have the impression that his critiques of evolutionary psychology elicited enthusiastic cheering and agreement from his readers, but these readers don’t seem to be posting objections to his new view, indicating, perhaps, either that they too have changed their minds, or that they are less willing to voice their dissent.

Related, there is already evidence that Myers is very sympathetic to evolutionary analyses of human behavior, even though he’s very bad at it when he tries. He applied an evolutionary sort of analysis to try to explain people’s positions on abortions, reasoning this way:

…it is in the man’s reproductive interests to have his genes propagated in any one pregnancy, while it is in the woman’s reproductive interests to bail out and try again if conditions aren’t optimal for any one pregnancy. This conflict is also played out in culture, as well as genetics — pro-choice is a pro-woman strategy, anti-abortion is a pro-man position. Sometimes, politics is a reflection of an evolutionary struggle, too.

From this, it is clear that Myers is clearly open to using fitness interests to explain policy positions – “Sometimes, politics is a reflections of an evolutionary struggle” – though he gets it wrong in the empirical sense that there’s basically no sex difference on this issue, and the best explanation around suggests that it’s more complex.

Second, I think punting on people like Myers underestimates modern readers and their ability to draw their own conclusions. Blogs are not hidden behind paywalls, and part of their raison d’être has to do with their being a forum for discussion among readers. Public blog dialogs are not private missives; they are a place for public discussions to start. So if Myers cannot be induced to engage with the field, this is not to say that his readers cannot be. “Shepherd of Internet trolls” he might be, but while many of his readers are likely to adopt his position and cheer his willfully ignorant bashing of the discipline, he has many readers, including dissenting commenters, many of whom link to information that undermines Myers’ claims. Some readers will follow these links, and look at the relevant source material for themselves. It seems to me that it’s a mistake to think of the blogosphere as a Clash of the Titans – Myers versus Coyne – with readers as spectators. A principal virtue of the blogosphere is that it’s a game everyone can play. If Myers cannot be persuaded to read in the discipline as Coyne did, that is not to say that some members of his audience cannot be.

Related, the creationists of the mind are not, to my way of thinking, like the garden variety creationist community. The fact that people read Myers’ blog, for instance, indicates an interest in science and the natural world. Similarly, the people from the community that brands itself “skeptics” are, I should think, curious, and interested in knowledge. Members of such communities are worth persuading, if for no other reason than they might eventually be in a position to contribute in one way or another.

Finally, it seems to me that in the modern scholarly climate, engaging creationists of the mind is sort of part of the job. If being a scientist entails a commitment to try to build and spread true ideas, then maybe there is also an obligation to try to defend against the spread of false ideas. Today, blogs are a major idea conduit, arguably more substantial than scientific journals in their ability to propagate ideas, good and bad. It feels like abdication to say that because such and such a community is stubborn, I will pretend not to notice them. My good friend and colleague Angela Duckworth has been persuading me of the importance of grit, the ability to persevere in effortful pursuits. If that means playing a never-ending game of Whack-a-Mole with the bad ideas of creationists of the mind, well, it seems to me that we have to be determined to get a little gritty.

What are Evolutionary Psychologists Talking About? An HBES 2013 retrospective

The 25th annual meeting of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society took place last week, from Tuesday the 16th to Saturday the 20th in South Beach, Miami. Deb Lieberman and Mike McCullough’s heroic, herculean efforts paid out in spades; the conference was intellectually among the richest ever and went off with no major logistical difficulties, though the weather could have been a touch better at the front end.

The quality of the plenaries, talks, and posters was, in my opinion, at an all-time high. I felt that in particular the student presentations I had the chance to see were exceptional, foreshadowing continued good things ahead for the field.

As always, characterizing the shape of the conference is a challenge, so I’ve adopted the same tactic I used for the Social Psychology conference (SPSP) back in January, looking at word counts from the program to get a lay of the land. This is only an imperfect way to try to capture the essence of the meeting, so take it all with a few grains of salt.

Ignoring the little words, the first item of substance, just as in the SPSP case, is social (289), with sexual (228) a somewhat distant second. Evolutionary (220), human (176), and sex (175) appear next. The term “sex” appears in various contexts – e.g., “sex differences,” “sex of subject,” etc. – and so doesn’t necessarily mean much, but “sexual” I think really does reflect what people are looking at, such as sexual strategies and sexual behavior. (I’d be interested in knowing what words pop out of an analysis like this one for the animal behavior conference. Anyone?)

The next substantive word is probably the biggest surprise: children (143). (Childhood also came in strong, at 60.) This represents, to me, one of the most dramatic shifts in the meeting, the increasing emphasis on development. The word appears because so much of the work drew on children as participants. Further, one of the plenary addresses was by a developmental psychologist Renee Baillargeon, and was, in a word, fantastic. Baillargeon reviewed evidence that very young children have intuitions and expectations about relatively complex social/moral concepts such as reciprocity, fairness, and ingroup/outgroup dynamics. For instance, young infants expect members of the same group to take revenge on behalf of a member of their own group against an outgroup member. In any case, members of the community seem increasingly to be looking at development, and I’ve previously highlighted the work of Annie Wertz, which is superlative; I was similarly very impressed with Kiley Hamlin’s presentation. The emerging increasing attention to development is not just visible at the conference: the winner of the best paper prize in the Society’s journal (see below) was also developmental.

Mate (136) and mating (123) are just downstream of children, with cooperation (128) in the same neighborhood, illustrating the community’s continued intense focus on this perennially interesting and controversial topic. In his remarks, David Buss made the astute observation that there were eight sessions about cooperation in the program but only one session on coercive violence. Aggression, for instance, mustered only 23 appearances, less than half that of humor (51). (Evolutionary psychologists seem to be obsessed with sex and non-violence… Heck, even the single session on violence included Steve Pinker’s presentation, which focused on how much less of it there is than there used to be.)

Attractiveness (120) comes as no real surprise, and terms for talking about social behavior fit in around here – group (113), partner (99), relationships (80) – as do terms that seem to reflect the roles that information-processing and game theory play in theorizing: strategies/strategy (97/68), information (96), cues (87), competition (75), mechanisms (64), and cognitive (57). Theory (113), evolution (92), psychology (92), evidence (92), reproductive (87), and hypothesis (86) make strong showings for obvious reasons. The continued attention to social groups other than just western populations was obvious to me as I attended talks, and is reflected in the frequencies of cultural (88) and culture (45); these terms do three times as well as genetic (34) and gene (10), which might surprise those who think that evolutionary psychology ignores culture but is obsessed with genes. Learning (51) was similarly well represented.

There was no shortage of discussion of punishment (86); the frequencies of facial/faces (81/50) show the continued interest in this topic, which was also the subject of Brad Duchaine’s excellent plenary address, which focused on various lines of evidence speaking to the question of whether there is face-specific architecture in the human mind. Some other words that caught my attention: status (62), disgust (56), health (56), testosterone (50), kin (49), economic (45), and orgasm (43). I thought moral/morality (44/23) would do better. Very generally, it seemed to me that there was more attention at this conference than in the past to hormones, health, emotions, and medicine, though I’m basing this only on these counts and my general sense.

I pause here to note some differences between the present list and the social psychology list. In particular, HBESers showed far less interest in stereotypes (2), prejudice (5), or identity (7), relative to the social psychology crowd. There were some appearances of the word self (72), but this term was far more popular with the social psychologists.

Between frequencies of 40 and 25, here are some terms that caught my eye:

40 species

40 investment

40 attractive

39 personality

39 disease

38 cooperative

38 biological

35 voices

34 genetic

34 environments

34 emotional

33 stress

33 heterosexual

33 dominance

32 threats

32 ovulation

32 aggression

31 romantic

31 adaptation

30 religious

30 political

30 emotions

30 copulatory

29 violence

29 preference

29 mechanism

29 birth

28 sperm

28 mates

28 maternal

28 costly

28 cognition

28 attraction

27 judgments

25 prosocial

25 couples

I’m not sure why, but there’s something amusing about the fact that coffee and brain both came in at 25.

So, that’s the crayon sketch of what the group is talking about. Here’s what the group values. Each year, several awards are given out. [UPDATED] the winners of the New Investigator award, which is given to the graduate student with the best paper are:

Kelly Gildersleeve: Meta-analytic Review of Cycle shifts in women’s mate preferences: Findings from complete set of 72 Published and unpublished effects

Michelle Ann Kline: How to learn about teaching: An evolutionary framework and empirical tests from Fiji

Next, the winner of the Poster Competition was Delphine De Smet for Gender differences in sibling detection: A facial EMG study of incest aversion.

The postdoc competition is open to anyone within five years of their PhD, and the winner is…

Jennifer Smith, for her paper, Evolution of cooperation among mammalian carnivores and its relevance to hominin.

(Smith is in a biology department, and my sense was that the proportion of biologists grew at this year’s conference though, again, I don’t have any actual data.)

Lifetime award winner, Sarah Hrdy

Next, the HBES Lifetime Career Award for Distinguished Scientific Contribution “is awarded to HBES members who have made distinguished theoretical or empirical contributions to basic research in evolution and human behavior.” This year’s (very deserving) winner is Sarah Hrdy.

Finally on the issue of awards, one of the most pleasant duties I have in my role at the Society’s journal, Evolution and Human Behavior, is announcing the winner of the award for the best paper, the Margo Ings Wilson Prize. which was established to honor the memory of one of the Society’s finest and dearest members, Margo Wilson (in memorium). Each year, the members of the editorial board choose the best paper of the previous year to receive this honor, which carries a cash prize of $1,500 to the first author. As always, the board’s decision was difficult due to the very high quality of the journal’s papers. Earning the position of first runner up for the prize was:

Lieberman, D., & Lobel, T. (2012). Kinship on the Kibbutz: coresidence duration predicts altruism, personal sexual aversions and moral attitudes among communally reared peers. Evolution & Human Behavior, 33(1), 26-34.

But the winner of this year’s award in Maciek Chudek and colleagues’ paper:

Chudek, M., Heller, S., Birch, S., & Henrich, J. (2012). Prestige-biased cultural learning: bystander’s differential attention to potential models influences children’s learning. Evolution and Human Behavior, 33(1), 46-56.

A few minor points. At this year’s conference, thanks to Lisa DeBruine, the Society (finally) has a facebook page. I hope that the page proves to be useful to members. (Please join, y’all.) On that note, if you have good photos from the conference you don’t mind sharing, please send your favorites to me and we’ll post some to the page.

Thanks again to Mike McCullough and Deb Lieberman for putting together an excellent conference, and to all the people, including students, competition judges, and administrative staff who put in countless hours into making the conference a success. Next year the conference will be held in Natal, Brazil, and registration will open in just a few months.

And, finally a blog note. I hope to get one or two more posts up, but I’ll be spending much of August convalescing, so I’ll be taking a break of a few weeks from posting.

This One Goes to Eleven, PZ Myers, and Other Punch Lines

There’s a great scene in the film This is Spinal Tap which gave rise to an expression that has so penetrated popular culture that it gets its own Wikipedia entry: “up to eleven.”

The film is a satire, following the fictitious band, Spinal Tap, documenting their travels and, to be sure, idiocies. In the scene, a member of the band is discussing an amplifier which is “very special” because the dials go to eleven, rather than the more traditional ten. “You’re on ten, all the way, up…” Nigel Tufnel explains, “Where can you go from there?… If we need that extra push, we go to eleven…” Marty (played by Rob Reiner) asks the obvious question: why not simply label the top-most setting ten? Nigel is clearly stumped, and can only weakly repeat that, well, this amp goes to eleven. (The scene, of course, can be found on YouTube, and you can watch it if you’re willing to endure the brief but inevitable advertisement.)

When you need that extra push…

Wikipedia tells me that this expression, going to eleven, “has come to refer to anything being exploited to its utmost abilities, or apparently exceeding them.” This is not, I should say, my experience of how the expression is used. I find that people use the expression to refer to a case in which an interlocutor seems manifestly, obtusely, even obstinately unable to see the logic of a relatively clear and unarguable point.

Which brings me to the question: why have Jerry Coyne’s views about evolutionary psychology changed so drastically while PZ Myers’ views have ossified?

I’ve been reading what Coyne has to say about evolutionary psychology for some time. Two and a half years ago, I wrote about how Coyne criticized the field as being not only wrong, but not even science. I found his hostility to the field – chastising us for not “policing” ourselves properly for instance – particularly puzzling given that his approach to non-humans is the same as the field’s approach to humans.

Coyne’s views have, if I may, evolved. In June of 2011, he maintained his hostility to the field broadly, but he did rise to the defense of Darwinian Medicine:

While I now think that Darwinian medicine is a useful and intriguing discipline, its practitioners must be careful not to fall into the same trap that’s snared many evolutionary psychologists: uncritical and untestable storytelling.

What a difference a couple of years makes. This past December, Coyne changed his tune, writing:

…those who dismiss evolutionary psychology on the grounds that it’s mere “storytelling” are not aware of how the field operates these days.

And, much more recently, just a few days ago, Coyne penned a blog post entitled “A defense of evolutionary psychology (mostly by Steve Pinker)” in which he defends the field — mostly, as he remarks parenthetically, by quoting an email from Pinker – against an as-yet unreformed foe of the discipline, PZ Myers.

Myers’ remarks derive from a post he wrote stemming from his appearance on a panel at something called “Convergence Day,” which seems to be a science-fiction and fantasy convention. I confess I find it surpassingly strange that there was a panel on evolutionary psychology at a science fiction conference, and quite a bit stranger that Myers would have been a participant on such a panel, given that he is, as his remarks indicate, innocent of any knowledge of the field.

Coyne sent Pinker some of Myers’ remarks that he made both in the post and the comments section, and Pinker provided some replies. What caught my attention was – to return to the business of going to eleven – the wholesale confusion Myers shows about the field. As I’ve remarked in the past, critics of the field, when they err, are not slightly missing the mark. Their confusion is deep and profound. It’s not like they are marksmen who can’t quite hit the center of the target; they’re holding the gun backwards. (See comments #9 and #10 on Myers’ post for remarks about what he takes the assumptions of the field to be.)

For instance, Myers gets the notion of modularity thoroughly wrong, taking it to be a spatial, rather than functional concept: “That behavioral features that have been selected for in our history are represented by modular components in the brain – again with rare exceptions, you can’t simply assign a behavioral role to a specific spot in the brain…” Consider this view he hangs on the field: “I’d also add that most evo psych studies assume a one-to-one mapping of hypothetical genes to behaviors. . .” And, thirdly, he writes: “Developmental plasticity vitiates most of the claims of evo psych.” As Coyne puts it, “’developmental plasticity’ does not stand as a dichotomous alternative to “evolved features.” Our developmental plasticity is to a large extent the product of evolution…” To readers with knowledge of the field, these claims about the field are easily seen to be just silly.

Given how many times each of these arguments – modularity, development, etc. – have been made in print, blogs, and talks, Myers’ continued confusion about them strikes me as goes-to-eleven baffling. Also baffling is how an organizer of a panel could invite him to participate given he demonstrates that he’s unaware of the most basic theoretical commitments of the field. (I don’t read Myers’ blog, but my completely naïve sense from reading the comments was that there was less piling on by his readers than I had seen in the past, and, in fact, one commenter linked to Coyne’s post. What comments there were on the topic of evolutionary psychology seemed to focus mostly on the gene/culture dichotomy. Interesting.)

Part of the reason that this struck me was that a couple of days before Coyne’s post appeared, a very short piece by Frans de Waal ran on big think. Entitled, “We Don’t Need an Evolutionary Explanation for Everything,” de Waal criticizes Randy Thornhill and Craig Palmer’s book, A Natural History of Rape, writing that the book “suggested that since men occasionally rape – but of course it’s not all men but a minority of them – it must be a natural phenomenon and it must have adaptive significance.” His complaint: “My problem with that kind of view is not everything that humans do needs to have an adaptive story.”

It’s hard to know precisely what de Waal means by having “adaptive significance,” but it sounds to me that his worry is that that it’s a mistake to assume that rape (or other traits) is an adaptation, and he understands Thornhill and Palmer to have done so. As I and others have repeatedly pointed out, they left this an open question, writing: “Although the question whether rape is an adaptation or a by-product cannot yet be definitively answered… ” (p. 84) and one section of their book was called, “Human Rape: Adaptation or Byproduct?”

The broader point is de Waal’s implication that there is some community of scholars out there – evolutionary psychologists, I presume, judging from his remarks in his closing paragraph – that assume that every trait is an adaptation. Again, given the countless times that various authors have clarified this point, the recurrence of this charge in general and the Thornhhill/Palmer charge in particular strike me again as incredibly puzzling.

As I indicated above, what strikes me about the sorts of errors that Myers makes about the field is that they demonstrate so little interest in trying to engage with it at even a cursory level, trying to understand the basic assumptions and key distinctions in the field. My sense is that Coyne’s change of mind came in no small part because of his decision to read something in the primary literature, in particular a paper by Confer et al. Now, Myers claims to have read in the primary literature, but the sorts of fundamental mistakes that Coyne identifies clearly belie this claim.

Which is why Myers’ remarks about the field always have, and always will, go to eleven.

[Edited to correct typos.]

APA, SCOTUS, & DOMA. And Mike Huckabee

Today Americans celebrate Independence Day, the anniversary of the day the founders of this nation backed their military rebellion against the constitutional monarchy with the fierce and fiery words of the Declaration of Independence. Many Americans view Independence Day as not only the birthday of their distinctive democratic republican form of government, but also the birthday of a certain set of freedoms, not the least of which has to do with the freedom to trample as a group on only a certain set of only certain other people’s (minority) freedoms.

The recent news cycle in the U.S. has devoted a certain amount of attention to one particular freedom which the Respective States may no longer abridge, the freedom of someone to enter into a marriage contract with a member of the same sex, the result of the recent Supreme Court decision on the issue of gay marriage, including their ruling on the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which “defended” marriage in the same way that smashing someone else’s radio “defends” yours.

Anyway, I’ve been interested in how people justify and motivate their positions on this contentious issue. A bit less than two years ago, I wrote about what I take to be the somewhat peculiar stand taken by the American Psychological Association (APA) toward gay marriage. Our friends at the APA were in favor of legalizing the practice, basing their position on the issue of harm. First, they said, the debate about gay marriage makes people feel bad. So that’s one reason to just legalize it already and end all debate. (Let’s see how that works out…) Second, they said, is that marriage is psychologically beneficial for the (gay) couples that enter into it. (Note the distinction between the claim that it’s good for society, broadly, and the claim that it’s good for the people who do it, narrowly.)

So, as good social scientists, they based their position on data: findings that many people would be better off, psychologically, if gay marriage were legalized.

Indeed, last week the APA hailed the decision as “a triumph for social science,” and continued to emphasize not any moral principle having to do with freedom, but rather the evidence, as the basis for its position.

In contrast, Mike Huckabee, former candidate for the nomination for the Republican presidential ticket in 2008, responding to the recent decision, based his opposition to the decision on moral consistency, saying:

If we’re determined to change the definition of marriage to accommodate how people feel and what they wish to do because of their mutual consent, then we should immediately release those incarcerated for practicing polygamy or bigamy…And, frankly, let’s make all consensual adult behaviors legal, whether prostitution, assisted suicide, or even drinking 16 ounce sodas in New York City.

Those unfamiliar with American politics might not immediately recognize it, but Huckabee was being sarcastic. He was not, in fact, advocating making prostitution or polygamy legal. (Those not familiar with New York politics might also need that last bit, the thing about sodas, explained to them.)

So, the APA opposes DOMA because the Act makes some people unhappy. Huckabee opposes overturning DOMA because of a slippery slope argument. If, he invites us to suppose, we let people do as they wish, where will that lead us, he asks, hands wringing. (Note: he is not, actually, wringing his hands in the video; “mutual consent” is as 2:26.) His argument seems to be that if we adopt this as a moral principle — letting people do what they want (as long, one presumes, as they aren’t hurting anyone, and there are no harmful side effects, etc.) – then we’re going to have to let people do some things that we just obviously don’t want to let people do, such as engage in polygamy, prostitution, and excessive soda consumption.

Huckabee isn’t the only one to worry about this slippery slope. Justice Sotomayor seemed to be worried as well. During oral arguments, she asked Ted Olson:

If you say that marriage is a fundamental right, what State restrictions could ever exist? Meaning, what State restrictions with respect to the number of people, with respect to — that could get married — the incest laws, the mother and child, assuming that they are the age — I can — I can accept that the State has probably an overbearing interest on — on protecting a child until they’re of age to marry, but what’s left?

In Sotomayor’s question is more or less the same idea implicit in Huckabee’s remarks, namely that whatever basis we use to let people marry members of the same sex, that basis better not force us to let people marry more than one other person, or a close blood relative, because those things are icky and we’d rather not let people do things that make us feel icky. Recall that the founders left Congress open to oppress minorities in certain respects, so the government is within its rights to keep its boot on the necks of would-be polygamists.

At this point it might be worth mentioning that as far as I can tell, the court didn’t base its opinion on either the data, as the APA would have it, or the notion of “mutual consent,” as Huckabee had it. I’m not a legal scholar, but I understand that the court’s basis was something to do with federalism and or “equal protection,” a clause in the 14th amendment.

Which brings me back to my main point, which is consistency. I and others have suggested, here and there, that people are often inconsistent in their moral views, using moral principles more or less as they become convenient to support the position they have already adopted for some reason or other. In this case, I don’t pretend to know Huckabee’s own moral principles, but it seems to me that he – and Sotomayor – have a good point which all of us academic freedom-loving liberals ought to ponder. (In contrast, I think the APA’s argument is a terrible one.) If we think that women ought to have the right to enter into a long-term contract with another woman, a contract which includes, presumably, sexually intimate acts, should we not also think, for example, that women ought to have the right to enter into short-term contracts – with men or with women – for shorter periods of time, a contract which includes, presumably, sexually intimate acts?

And, related, it seems to me that we ought to be careful in putting our chips where the APA places them. Suppose that research shows that the discussions of father/daughter incestuous marriages are causing psychological harm. Will the APA come out in favor of legalization? Suppose research shows that people in plural marriages are happy, and children in such marriages are well adjusted? (And, to return to a point above, it could be that polygamy is good for people in it, on average, but bad for the broader society.) What position will the APA take then? (For what it’s worth, the New York Times recently had an interesting piece on the result of the fact that prostitution is still a black market transaction in most of the country.) My sense is that the APA is less wedded to consistency than Huckabee seems to be.

Anyway, happy independence day to all you Americans out there, and I encourage you all to spend some time today thinking of the contracts and voluntary mutually beneficial transactions you think the government ought to continue to suppress as we celebrate our “freedom.”

Cultural and biological evolutionary perspectives on disgust – oil and water or peas and carrots?

Guest blogger, Josh Tybur

Today’s post is by my friend and collaboroator, Josh Tybur. His biography appears at the end of the post. – Rob Kurzban

Disgust is, at present, a hot topic in psychology. It is also a topic that has become thoroughly “evolutionized.” That is, with a few exceptions, most researchers, whether they label themselves evolutionary psychologists or not, agree that disgust toward things like maggot infested carcasses and juicy piles of vomit has a specific function that has been shaped via natural selection: to motivate the avoidance of the pathogens potentially contained within the disgust-eliciting object.

People are not only disgusted by corpses and vomit, though. They self-report disgust and make disgust faces when they think about having sex with a close relative, when they watch sexually explicit videos, when they hear about others having sex with a close relative, when they hear about people stealing from old ladies, and when they hear about others swindling people out of money. A job for disgust researchers, then, has been to develop and test theories that can explain why and how so many things seem to elicit disgust.

In a recent paper, some colleagues and I argued that, although researchers generally agree that a comprehensive understanding of disgust must use an evolutionary perspective, two of the core contributions of mainstream evolutionary psychology have not been all that well integrated into disgust research and theory.

First, we suggested that some well-cited hypotheses of non-pathogen-avoidance evolved functions of disgust (e.g., to neutralize reminders that humans are animals, and the purported existential terror that accompanies such reminders) seem unlikely given the posited adaptive problems that would have shaped the evolution of disgust. We also discussed alternative selection pressures that may have shaped the evolution of disgust.

Second, we suggested that researchers have typically not adopted one of the key insights offered by evolutionary psychology: that of how modular, functionally specific information processing mechanisms should be structured for psychological adaptations to be executed. We argued that increased attention to both of these issues can be useful for generating testable hypotheses regarding both the form and the function of disgust (see Cosmides and Tooby’s primer on evolutionary psychology for a review of these principles, and a nice example about dung beetles and disgust).

Paul Rozin and Jon Haidt (hereafter RH), who have had tremendous impact on disgust research, recently wrote a commentary on our proposal in Trends in Cognitive Sciences. In their piece, RH suggested that our approach can be useful, but that it is limited “because [it] ignores the powerful role of cultural evolution.” RH concluded their commentary by stating, “Cultural and biological evolution…should not be seen as providing mutually exclusive views. We urge an integration.”

Now, I find cultural evolution pretty cool, and my co-authors and I took some efforts into crediting its importance in our proposal. Indeed, a quick search of our paper revealed 19 instances of words containing “cultur*” (excluding references and headings), including some explicit references to the importance of cultural evolution:

Other aspects of cross-cultural variability in disgust could arise via cultural evolutionary processes

individuals must acquire culturally evolved information…they need to acquire information from their social group to deploy disgust in a fitness promoting fashion

if rules evolve culturally (Richerson & Boyd, 2005), expressions of moral disgust could be targeted toward violations of culturally specific rules

We never wrote – and I hope that we didn’t imply – that cultural and biological evolution are mutually exclusive perspectives, or that cultural evolution should be ignored when investigating disgust. Still, RH pose an interesting question: how can a consideration of cultural evolution help us understand disgust? I’ll briefly mention two ideas, both of which concern pathogen disgust and food.

First, how might cultural evolution influence which cues are taken as input into the pathogen disgust system? Readers who have traveled internationally (especially to non-WEIRD countries, if you happen to be WEIRD yourself) – or anyone who has seen Bizarre Foods with Andrew Zimmern – know that many of the foods happily eaten in other cultures can seem pretty disgusting to people from other cultures. Why might cultural variability in the types of food that elicit disgust exist?

We suggested that putting things in the mouth increases the probability of pathogen acquisition compared to not putting things in the mouth, and swallowing things increases this risk further. The best pathogen avoidance strategy, then, is to never put anything in the mouth. This type of strategy, while good for mitigating the fitness costs imposed by infectious disease, is poor for getting calories and nutrients. But how do you know which things you should put in your mouth and ingest? Generally, this question underlies the omnivore’s dilemma, a term coined by Paul Rozin (and adopted as the title of a great book by Michael Pollan).

It’s probably a good idea to watch what other people are eating when you’re young, and to further engage in a little trial by error to see if some things that seem similar to “acceptable” foods (e.g., novel berries) have a nice taste, which presumably informs the probability that they contain calories (good) or toxins (bad). Hence, the information processing structures that underlie learning what foods one should eat, and what foods should elicit disgust, should have evolved to take both individual experience and socially (i.e., culturally) transmitted information as input.

The types of foods that someone sees other people eating – and the rituals that go into acquiring and preparing those foods – are presumably shaped by cultural evolution. If certain rituals are more successfully transmitted in a particular ecology than other rituals, then the types of potentially edible plants and animals that are viewed as “disgusting” versus “delicious” can vary quite a bit across culture.

Second, how might cultural evolution have contributed to the evolution of the information processing structures underlying pathogen disgust – that is, the universal psychological architecture of interest to evolutionary psychologists?

Dan Fessler and Carlos Navarrete have summarized the literature suggesting that aversions to meats are easier to condition than aversions to non-meats, that food taboos involving meat outnumber food taboos involving non-meats cross-culturally, and that people only eat a small proportion of the total meats available in the local ecology. Presumably, the cultural evolution of tool use and hunting techniques resulted in humans consuming more meat. Greater consumption of meat in turn led to new vulnerabilities to pathogens. This in turn constituted a selection pressure that might have then shaped the information processing structures underlying pathogen disgust to process “meat” stimuli in a functionally specialized manner.

I’ll close by posing a few “food for thought” questions:

In what other ways might cultural evolution have shaped the information processing structures underlying disgust?

Why might some things elicit disgust more consistently across cultures than others?

And – as a bonus for those who are familiar with the animal reminder theory of disgust advocated by RH, but not favored by others of us – what information processing structures might underlie animal reminder disgust?

References

Fessler, D. M. T., & Navarrete, C. D. (2003). Meat is good to taboo: Dietary proscriptions as a product of the interaction of psychological mechanisms and social processes. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 3, 1–40.

Rozin, P., & Haidt, J. (in press). The domains of disgust and their origins: contrasting biological and cultural evolutionary accounts. Trends in Cognitive Sciences.

Tybur, J.M., Lieberman, D., Kurzban, R. & DeScioli, P. (2013). Disgust: Evolved function and structure. Psychological Review, 120, 65-84.

Josh Tybur is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Social and Organizational Psychology at VU University in Amsterdam. He received his PhD in evolutionary psychology from the University of New Mexico in 2009. His research is currently focused on understanding some of the puzzles posed by disgust, and how the solutions to these puzzles can inform our understanding of food preferences and aversions, mating psychology, and moral judgment.

2012 Impact Factors – Evolutionary Psychology and Evolution & Human Behavior

The 2012 Impact Factors (IF) – one measure of the influence of a scholarly journal – have been released. Impact factors are controversial, and what they are measuring is richly debated. I have no strong position on this issue, though in general I applaud the proliferation of different metrics for evaluating journals.

In any case, for better or worse, the new 2012 IFs are out. Evolutionary Psychology, the journal that hosts this blog, leapt from last year’s 1.055 to 1.704, the highest the journal has ever achieved. The present Impact Factor puts Evolutionary Psychology in the neighborhood of Personality and Individual Differences (1.807), European Journal of Social Psychology (1.667), Sex Roles (1.531), and, another evolutionary journal, Human Nature (1.814). A nice neighborhood. Kudos to the editorial team, especially Todd Shackelford, who has worked tirelessly over the last several years to put the journal on the path that it is currently traveling.

The other journal I’ll mention is the official journal of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society, Evolution and Human Behavior, which increased from 3.113 in 2011 to 3.946, also the highest it has ever been.

The other journal I’ll mention is the official journal of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society, Evolution and Human Behavior, which increased from 3.113 in 2011 to 3.946, also the highest it has ever been.

One way to put this value in perspective is to place it among journals in social psychology. Set against the 60 journals listed in the Journal Citation Reports, Evolution and Human Behavior would rank 4th, behind Personality and Social Psychology Review, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, and Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (4.877). In anthropology, E&HB would be third of the 83 listed, behind Journal of Peasant Studies (superstar paper: “Globalisation and the foreignisation of space: Seven processes driving the current global land grab” by A. Zoomers, cited 144 times according to Harzing’s) and the Journal of Human Evolution (4.094). (Current Anthropology is at 2.740, which surprised me because I thought it would higher.) Ranked against economics journals, E&HB would be 4th of the 332 listed by JCR. (The journal is grouped by Reuters under Biological Psychology, and sits second, below Behavioral and Brain Sciences with its whopping 18.571 Impact Factor.)

The bulk of the credit for these numbers goes, of course, to the authors of the papers. Still, I do think that it’s worthwhile to take a moment to note that the present quality of the journals, such as they are, owes a tremendous debt to the prior editors of the journals. I have some slight worry that some of the younger generation in the field might not know that Martin Daly and Margo Wilson edited Evolution and Human Behavior (starting before, in fact, it was called Evolution and Human Behavior) from 1997 to 2005, and are to be credited with setting the journal on its present trajectory. Steve Gaulin, Dan Fessler, and Martie Haselton are similarly no longer actively editing, but they each and all shepherded the journal through the 2000’s. The present group of editors stands on the shoulders of the efforts of all of these scholars who came before, and I, for one, am deeply grateful for all their hard work.

“Pathological Altruism”: A New Idea that Robert Burns Discussed in 1785

[UPDATED, fixing a bad mistake the first time ’round. Sorry. In my prior version, I indicated that Oakley required that the results of the acts be hard to predict, rather than what she actually said, which is that they are easy to predict. I regret the error.]

What a panic’s in thy breastie!

The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has a collection of papers, based on a colloquium “which aims to survey what has been learned about the human “mental machinery” since Darwin’s insights.” I haven’t read all of them, but I think it likely that readers of this blog will find some, even many, to be of interest.

One paper did catch my attention, in part because it touches, if only gently, a topic I’ve mulled before having to do with the strangely contentious issue of how to define the term “altruism.”

Before I get to the paper, here is a recent remark by John Tooby in the context of the recent Edge discussion of group selection on the issue that amuses:

For example, using the definition of selfishness and altruism that biologists use, a loving and self-sacrificing mother is acting selfishly, while a drug addicted mother who starves her children to give all her money to her dealer is an altruist (i.e., she is lowering her own fitness in a way that increases a nonrelative’s).

Now, one might quibble with the former part of the example, insofar as mom is increasing her own inclusive fitness as well as baby’s, thus making the action (still somewhat oddly) “cooperation,” but the addict does seem to conform to the definition of altruism insofar as one is committed to definitions that refer only to the fitness effects of a given behavior.

A key advantage of the behavioral definition of altruism, for which we have Hamilton to thank, is that it takes a term rooted in folk psychology and frees us from having to worry about the perennially tricky notion of intentions. Because the definition refers only to behavior, we don’t need to worry if mother wanted to help her child (or the drug dealer), and equally we don’t have to worry if a worker ant wants to aid her colony-sisters. Defining altruism in behavioral terms, while subject to certain sorts of worries, at least purges intentions from the whole business.

And now to the PNAS article. Barbara Oakley, in a piece called “Concepts and implications of altruism bias and pathological altruism,” seems to have surrendered any clarity gained by behavioral definitions. She writes:

Pathological altruism can be conceived as behavior in which attempts to promote the welfare of another, or others, results instead in harm that an external observer would conclude was reasonably foreseeable.

Pathological altruism – in contrast to garden variety altruism – turns on intentions. In particular, for something to be pathologically altruistic, the doer of the deed must have the intention of helping. Further, mental states are important for the second condition, having to do with what a third party could “reasonably” foresee. When I try to put this slightly more formally, it seems to me that she means that PA is defined thusly:

- I do X AND

- I intend to benefit you by Xing AND

- doing X caused result R, a (net, long term) harm to you AND

- R was foreseeable.

[I updated this because I got condition 4 backwards when I originally wrote this. My apologies to readers and to the author. I’ve removed all the bits I got wrong. I hope.]

It seems to me that while Oakly has identified something interesting, that something already has a name. Actually, it has several names, such as “myopic,” “short-sighted,” or perhaps “ being impatient.” The phenomenon is essentially that people sometimes choose to pursue short term goals (keeping brother out of pain and out of trouble with the boss) even though this conflicts with achieving some long term desirable outcome (ending brother’s addiction to painkillers).

When Oakely moves to the non-human animal world, the link between observations and behavior is even more obscure. She suggests that “pathological altruism can be thought of as a pattern of nurturing or beneficial behavior with evolutionarily unsuccessful consequences,” seemingly switching the definition away from her previous commitments, and uses the example of “the unwitting hosts of brood-parasitism, as with the wood thrush who devotes substantial resources to raising the offspring of cowbirds.” It’s not clear to me that any of the key elements of pathological altruism are satisfied here. And, of course, this area has been well explored and explained with concepts like manipulation and deception in the literature in behavioral ecology.

As for the bottom line, Oakley is explicit about what this might be: “The bottom line is that the heartfelt, emotional basis of our good intentions can mislead us about what is truly helpful for others.” This is almost certainly true. Because the world is complex, and because behaviors have effects at different time scales, there are many ways in which my (intended) help in the short term will make you worse off in the long term. As Adam Smith and (many) others have noted, the Law of Unintended Consequences virtually guarantees this, and is unlikely to be repealed any time soon: interventions from the scale of the well-meaning brother to international aid – made with the best of intentions – often lead to pervasive harm and suffering. (I myself find this idea to be interesting, and have discussed it from time to time.)

The same is true, of course, for the effects of my behavior on me because my choices have cascades of consequences. That is, choices I make to make me happy in the short term – eating cake, watching television, venting my spleen – have long-term negative effects. Am I being pathologically selfish?

To return to the point above, definitions are important, and it seems to me that this is especially the case in the context of talking about “altruism” and related concepts from biology when talking about humans. With humans, it is more important than in other species to be vigilant about using intentional language because it is with humans that it is most tempting. While the definition of altruism some use might not be optimal, Oakley’s foray into coining new terms seems to me to take steps backwards; my hope is that this use of terminology isn’t broadly adopted. (For a relatively recent paper on some of these issues, see West et al., 2007).

In short, the fact that pursuing short term happiness sometimes, maybe even often leads to negative longer term consequences, it seems to me, has little to do with either pathology or altruism. One reason for this is that indulging many of our short term appetites have long-term negative consequences, a topic I and others have discussed in various places. Moreover, because the world is complex, sometimes when we try to help, we harm instead. So, yes, people make mistakes. For instance, one mistake that a person might make is confusing a new idea for one that has been around for a very long time. These things do happen.

Oakley places no small importance on her idea, writing that “pathological altruism, in other words, is not a minor, inconsequential offshoot of the study of altruism but instead is a topic of overwhelming scientific and public importance.” So it’s all Kind of a Big Deal. If the real point is that things don’t go as well as we had planned, well, my good friend Bobby Burns, I think, said it best:

But Mousie, thou art no thy lane,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!– From “To a Mouse,” 1785

(But, seriously, check out the other papers in PNAS.)

Is Theon Greyjoy Like a Secret?

I’m writing this post having just come back from beautiful Annville Pennsylvania, the home of Lebanon Valley College (motto: “Now with more corn!”) and this year’s meeting of the annual Northeastern Evolutionary Psychology Society meeting. I was fortunate to attend a number of interesting talks, though, with all due respect to this year’s lineup, I have to say that I found more to love at last year’s meeting, though it should be borne in mind that at last year’s conference, held at Plymouth State University (motto: “Education. Without the Income Tax!”) during one of the breaks I went to a chili eating contest on campus which was hot, hot, hot.

Anyway, I’m back at Penn now (motto: “Hey. At least we’re not in New Haven“), and I thought I’d write about one talk that particularly caught my attention, by Jack Demarest and Joanna Raymundo, both of Monmouth University (motto: “Not too close to Newark!”), entitled, “Crossing the line: When does having “just a friend” become potential infidelity in extrapair relationships?” and this year’s first runner-up for the award for most punctuation marks in a title, coming in at three, just shy of Barry Kuhle’s impressive four. (The abstracts can be found in the program.) This will connect to Theon Greyjoy by and by, but it’s true you have to work for it a bit.

As you might guess from the title, the authors were interested in the continuum of acts that your mate might engage in, and the point at which increasingly intimate acts cross the line from acceptable to unacceptable, according to their student sample. That is, we all know that people would say that having sex with someone else is “unacceptable” in the context of a relationship, but what about, to use their favored example, lap sitting? Over or under the line? They gave subjects a list of seven acts that one’s partner might engage in with an opposite sex friend, and asked respondents to rate how “acceptable” each of the acts would be. If my notes are right, the acts included: going to class together, having lunch, going to the movies, having dinner together, going to a bar at night, excessive texting, and having intimate conversations that he/she does not share. (Lap-sitting was left off the list, presumably as an avenue for future research. I might also note that it seems to me that “excessive texting” prejudges the issue, as it already implies that it’s too much, as opposed to just a lot.)

It turns out that the line is crossed fairly early in this list, with going to class and having lunch rated below the midpoint for acceptable, while the rest weren’t. Subjects were particularly irritated with mates texting with a opposite sex friend and having intimate private chats with them.

I don’t think these findings are too surprising, though as with many unsurprising findings there is something nice about having some measurements instead of just shared intuitions about how it would come out. The authors also found some sex differences, with women rating the behaviors more unacceptable.

The talk got me thinking a little bit about secrets, which, in previous work (with Peter DeScioli) turned out to be important in the context of friendship: the extent to which people reported sharing secrets with a friend was a strong predictor of the strength of that friendship. Secret sharing did better than seemingly important variables such as the length of the friendship and the frequency with which the friend was seen. Why do secrets make friendships strong? And why are people so irritated when their friends and mates share secrets to which they themselves are not privy? And what is the relationship between the answers to these two questions?

Clearly one danger posed by secrets is that damaging information about oneself might be moving from one person to the other. This is transparently a reason to be wary of secret-sharing, but I don’t think it’s the whole story. Suppose you found out that your mate shared a secret along the lines that they had cheated on their SATs, tortured a bunny, or voted Republican. Even sharing secrets of such dark deeds that have nothing to do with you would, I think, be found irritating by most people.

What am I hiding in my big cloak?

So, another way to think about secrets is that they’re like hostages. Consider Theon Greyjoy, a character in Game of Thrones, heir to the throne of the Iron Islands, raised by the Starks in Winterfell. (For non-watchers of the show, you should simply think of this as one member of one coalition being held hostage by another coalition.) By having a hostage at Winterfell, the good behavior of the Iron Islands was ensured because if the Islands acted aggressively, the hostage could be killed. When hostage exchange is mutual, as was common in Europe in the Middle Ages, groups or coalitions has good reason to trust their would-be ally because each one was vulnerable to the other. If I know that you know that I can harm your hostage if you betray me, then I can be much more confident that you won’t do so.

Secrets might work a bit like this. When I tell you a secret that would damage me if it got out, I’m in effect giving you a hostage to kill (information to disclose) if and when you wish. Making myself vulnerable in this way can actually be a strategic advantage in that you now know that I’m unlikely to betray you, out of fear that my secret will be revealed. My guaranteed loyalty to you makes me a better ally than one whose loyalty could not be assured. If we both share secrets with one another, then we are bound to one another reciprocally, potentially making our friendship strong and stable.

This is all well and good, but of course the key point is that while alliances are good for the people who are in them, they represent threats to others. In political contexts, whether the fictitious Game of Thrones or real international relations, others’ alliances represent threats because the participating coalitions can join forces and gang up on you: that’s the whole point of alliances. To the extent that one thinks that friendships are alliances (as opposed to, for instance, exchange relations), as some of us do, others’ close friendships with your friends are threats to you as well. This explains why it’s so irritating to find out that your best friend is sharing secrets with someone else: the strength of that friendship alliance between your best friend and another person constitutes a threat to your best-friendship. It’s bad to lose your place at the top of someone else’s list of friends.

And of course this holds for the mating domain as well, in which you really don’t want to lose your place at the top of the queue. I think this is a part of the reason that sharing secrets carries a sense of intimacy and why people don’t want their mates sharing secrets. Doing so is a way to build the strength of the relationship because secrets are like hostages, ensuring each party that the other will remain loyal. And you don’t want your best friend or your mate loyal to others, especially not more than they are to you.

As with real hostages, the solution is not without problems. Just as hostages can die, secrets can lose their value, say, if the information becomes widely known or is for some reason no longer relevant. For instance, the world can change in such a way that the secret is no longer damaging if it gets out: knowing that someone was (secretly) gay might in the past have been a powerful thing to know, but now it’s not much more scandalous than knowing someone is (secretly) a Cincinnati Bengals fan. This situation can be particularly vexing if one person in a pair’s secrets becomes powerless while the other’s does not, leading to a power asymmetry where once there was equality.

It’s important to note that explanation is unsatisfying for some kinds of secrets. Information that isn’t dangerous to the speaker if it got out, for instance, isn’t well covered by this explanation, yet my sense is that people wouldn’t want their mates secretly sharing even innocuous information with a potential rival suitor. If you found out your mate was exchanging literary critiques with an opposite-sex friend, but doing so secretly, this would still likely be vexing. We care about the fact that both parties are communicating secretly in and of itself. It could be that this is simply because by the very nature of secrets, one doesn’t know the content of the information exchanged, and so anything passed along secret channels is a potential threat. And, of course, there’s a recursive property: the fact that one is passing secrets to someone else is itself a secret, adding to the potential to erode trust.

Ultimately, what is and is not acceptable in relationships probably boils down to the perception of risk to the relationship. Going to class with someone doesn’t signal to either party or others than there is anything special in the relationship, and constitutes only a relatively minor threat. But when I give you one of my secrets, I simultaneously signal my trust in you and give you leverage, both of which can be to my advantage, and, consequently, to others’ disadvantage.

So that’s the secret of secrets.

But don’t tell anyone.

Are All Dictator Game Results Artifacts?

You walk into a laboratory, and you read a set of instructions that tell you that your task is to decide how much of a $10 pie you want to give to an anonymous other person who signed up for the experimental session.

This describes, more or less, the Dictator Game, a staple of behavioral economics with a history dating back more than a quarter of a century. The Dictator Game (DG) might not be the drosophila melanogaster of behavioral economics – the Prisoner’s Dilemma can lay plausible claim to that prized analogy – but it could reasonably aspire to an only slightly more modest title, perhaps the e. coli of the discipline. Since the original work, more than 20,000 observations in the DG have been reported.

The first thing to be careful to mark about the DG is that running such a game does not, of course, in itself, constitute an experiment. The Dictator Game, in isolation, is better understood as a measuring tool. It measures, in some sense, generosity. If you like to think that people have “(pro-)social preferences,” – that people are happy when others are happy (as I am) – then measuring how much money a person gives to another individual in the carefully controlled setting of the DG is one way to assess the strength of this preference.

The DG can be, and has been, used as a control condition. So, for instance, early work used the DG as a control condition for the Ultimatum Game (UG), which is like the Dictator Game except that the first player’s proposed split can be rejected by the second player, in which case both get nothing. Comparing the DG and UG, so the logic went, allows the experimenter to measure how much more people propose in the UG because of the fear of the offer being rejected as opposed to, loosely, simply being generous. The DG, in this sense, controls for pro-social preferences as an explanation in the UG.

All but one implementation of the Dictator Game, as far as I know, until recently, have had something potentially important in common: the people playing the game know that they were in an experiment. This circumstance, of course, is very difficult to avoid, and obviously this claim can be made of the vast array of methods used across the experimental social science literature. To be sure, conducting experiments on subjects without them being aware of the fact that they are in an experiment is difficult, not to mention potentially unethical. Still, some of us have wondered for some time if there is something special about this fact when it comes to the Dictator Game. After all, we each are in Dictator Games every time we walk into the world with money in our pockets. We could, if we wished, split the cash we’re carrying with a stranger in the street. My casual observation of my own behavior suggests that if my pro-social preferences were measured this way, I would come across as stingy indeed or, as economists would have it, “rational.”

Further, there is something pragmatically odd about the “game.” (Even Wittgenstein might have balked at calling the Dictator Game a “game,” and he famously cast the net for this term broadly indeed.) Subjects in this experiment are faced with one decision, one lever to press, or not press, as it were. Subjects who give nothing are in the peculiar position of coming to a lab, reading instructions, and then, roughly, doing nothing at all and collecting their loot. It’s easy to imagine that subjects think there’s all something funny about this, and feel some urge to push on the single lever the experimenter has given them to play with, if only a little bit.