A new Indian nationalism gradually began to take faltering baby steps around the 1870s and 80s and as the newly nationalistic Indians looked around them for inspiration, many of them embraced Japan as a model. Here was an Asian nation that had rapidly begun to emerge as an equal of European imperialist powers and sought to repay them in their own coin. This fascination with all things Japanese was particularly strong amongst the Bengali intelligentsia who were also at the forefront of the new nationalism. When Japan finally managed to hand out a military defeat to Russia, seen largely to be an European power, in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, the fascination began to evolve into adoration. Artistic collaborations and political contacts began to cultivate a new ideal of Pan-Asianism. Pulp novels evoked deeper cultural kinship between Bengalis and the Japanese. So much so that many Bengalis even began naming their sons after Japanese generals during the decade leading up to the Great War.

This admiration and interest also spilled over in the world of commerce. As Japanese manufacturers in a newly industrializing economy sought out new markets, Indian and Bengali businessmen sought contacts beyond the older European sources on importation. This mutual interest quickly led to the flooding of the markets of Calcutta and beyond by a number of cheap Japanese goods. Japanese-made matches, for instance, almost completely evicted the earlier Bohemian- and Swedish-made matches.

One such cheap product that flooded Bengali markets were Japanese patent medicines. Amongst these, particularly popular was a stomachic called Jintan. Though the medical claims of Jintan have long since waned, the product remains on the market till this day as a breath freshner. The product, created by the combination of cinnamon, clove, cumin, mint, amomi, etc., had been developed in the late nineteenth century by Morishita Hiroshi, the son of a priest.

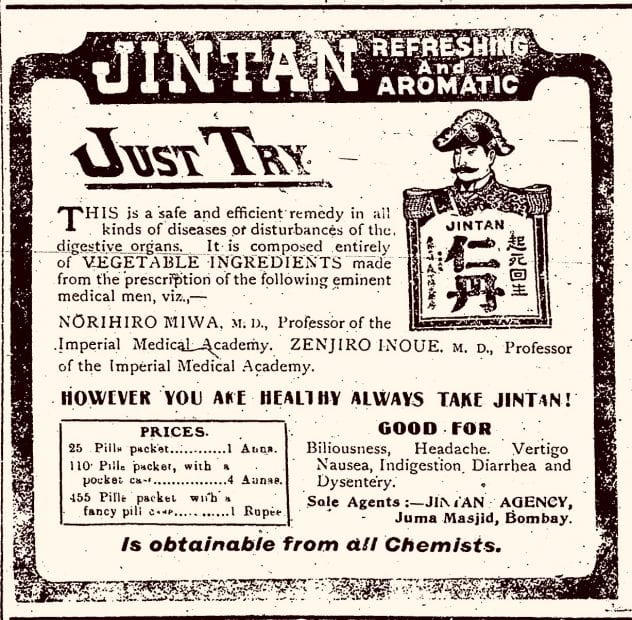

Morishita’s success was in part attributable to his innovative marketing. After the Russo-Japanese War for instance, Morishita developed a highly evocative trademark depicting a Meiji Era soldier. He also backed up extensive print advertising with a variety of gift-schemes and promotional offers. Precisely when Jintan began to be marketed in British India is unclear, but there were certainly voluminous newspaper advertisements for the product in Indian newspapers just prior to the First World War.

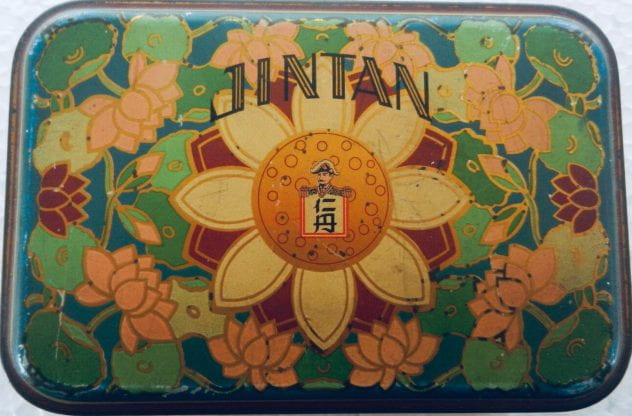

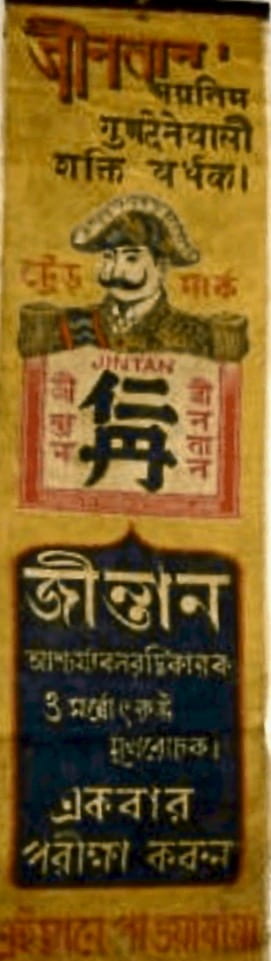

Unfortunately, whereas much of the rich and beautiful Jintan advertising in East and South East Asia has been preserved, in India with the sole exception of small decorated tins in which Jintan pills were marketed, very little of the early advertising has survived. The few tins that have survived however, like the more voluminous newspaper advertisements, are important for showing how Jintan’s signature trademark with the mustachioed Meiji soldier was subtly adapted to the Indian market with the prominent insertion of Indian scripts.

A much more prominent and striking testament of this adaptation can be seen in a small number of paper hand fans that I have managed to find over the years. The paper hand fan itself, as an object, obviously evoked traditional images of East Asia. The early examples also prominently displayed upon them paintings of beautiful women in kimonos waving a similar hand fan. Upon the back, the name of Morishita and the factory in Osaka were prominently displayed.

Later images however, were remarkably different. The Japanese women gave way to sari-clad Indian women and the snow-drenched landscapes made way for luscious tropical gardenscapes. Upon the back too, the prominence given to Morishita and Osaka were replaced by the name and address of the local importer, Partabmull Gobindram of Khangraputty Street, Calcutta. One could no longer tell if the iconic image of a modern factory was the one in Osaka or somewhere in Calcutta. Indeed, with the sole exception of the image of the Meiji soldier and the Japanese kanji for Jintan, no other sign remained of the products’ Japanese origins.

The images used were in fact famous images published by the Raja Ravi Varma Press. I am not certain as to whether the image was actually syndicated or merely copied, but at least one of the images used, namely, Mohini, was a very famous Ravi Varma image that appeared in lithographs, match labels and postcards. Yet, upon looking closely, I think one can discern a faint hint of a Japanese ideal of feminine beauty upon Jintan’s Mohini. I do not know if the Jintan Mohini was in fact used anywhere outside of British India. I would not be surprised if it was, since I have certainly seen match-labels printed in Japan that used versions of the Mohini image.

The Jintan fans are cheap advertising props. Ephemeral and effervescent. Yet, in them we catch a glimpse of the many subtle ways in which Indian and Japanese modernities blended, braided, and influenced each other.

Acknowledgements:- Photographs courtesy Manjita Mukharji.

https://tenziku.com/indiantilefromjapan/#i

[…] is also an interesting article on Japan-India commercial relations. Here it says that the admiration to Japan following its […]