PCSSM Writer Vanessa Schipani, in reflecting on Penn’s Climate Week, makes an argument for optimism in the aftermath of Hurricanes Helene and Milton and on the cusp of the 2024 U.S. election.

I grew up in Florida and have distinct memories of the destruction Hurricane Andrew inflicted on my state in 1992. I remember hunkering down, my dad nailing plywood over our very Floridian jalousie windows, filling up the bathtub with water, listening to a battery radio by candlelight and hoping our quaint, two bedroom cinderblock house would hold up. Luckily for us, it did.

My extended family in Miami were less fortunate. Meteorologists initially expected Andrew to make landfall closer to Broward County, where we lived, but at the last minute the storm ‘wobbled’ and hit Miami-Dade County head on instead.

My aunt and cousins lost their roof and had to live with my grandparents for a long while after that to get back on their feet. Unfortunately, they were far from alone. At the time, Andrew was the costliest hurricane ever to hit the United States, later to be topped by Hurricane Katrina, which still holds the record by a long shot.

To Floridians, hurricanes, including their unpredictability, have long been a part of life. But something felt different to me about Milton and Helene. For one, my family in Asheville, North Carolina – the same aunt and cousins who lost their home to Andrew – thought they were safe from major hurricanes by moving to the mountains. The fact that they weren’t was a wake-up call to them and unfortunately to many of their neighbors.

When it came to Milton, the difference between past storms and this one first became apparent to me when I watched a clip of veteran meteorologist John Morales come to tears while describing how Milton “dropped 50 millibars in 10 hours.” For those who aren’t familiar with how scientists measure hurricane strength, this might seem like an odd thing to get emotional about.

So, here’s a primer: There’s an inverse relationship between a hurricane’s atmospheric pressure, measured in millibars, and its windspeed. This is due to the fact that gases, which make up the air, move from high- to low-pressure areas; so, the lower the hurricane’s pressure compared to outside the storm, the faster the storm’s windspeed.

When Milton’s pressure dropped rapidly, as Morales said, its windspeed rapidly increased – so fast, in fact, that it set a record: In just two days it went from a tropical depression to a Category 5 hurricane faster than any other storm in history, where most of that growth occurred over the 10 hour period that brought Morales to tears.

Still choking up, Morales also pointed to a driver of that rapid growth: “The seas are so incredibly hot, record hot,” adding, “you know what’s driving that.” You guessed it, it’s climate change.

Why are warmer oceans fuel for hurricanes? Because they cause hurricanes to drop in pressure, which then causes windspeeds to rise. Warm oceans also cause hurricanes to carry more rain because warmer water evaporates, making the air more humid. And more rain means more flooding.

The storms themselves were enough to make me question whether we’d be able to get ourselves out of this mess. But the conspiracy theories about the storms really tested my ability to hold out hope.

Some questioned whether the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) would have enough funds to help North Carolina and Florida recover (they do). Others claimed the storms were geoengineered in some way with the goal of targeting a specific part of the country (they weren’t).

In a weird twist, the conspiracy theorists were right about something – that humans were involved. As Yishan Wong, CEO of Terraformation, a forest restoration company, tweeted: “Conspiracy theorists who keep saying there’s ‘no way’ the hurricane could have intensified so much without some human cause are so close to getting it.” This irony was more painful than funny to me.

Then, over the course of attending two events put on by Penn’s Center for Science, Sustainability and the Media (PCSSM) during Penn’s Climate Week from October 14-18, I found reason to keep my chin up. The first event I attended on October 14 examined how we can get more scientists, engineers, and healthcare professionals – in short, data-driven people – into office.

The event featured Shaugnessy Naughton, the President of 314 Action, an organization with that exact goal, and Monica Taylor, Chair of the Delaware County Council and an Associate Professor of Public Health at Temple University, along with Michael Mann, PCSSM’s Director. Parrish Bergquist, an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Penn, interviewed the group.

Naughton’s story inspired me because she identified a problem – that there weren’t enough scientists in office – and, even after failing to win a race for Congress in Pennsylvania’s 8th District, persevered and founded 314 Action. So far, the organization has helped elect three U.S. Senators and over a dozen members of Congress, and has endorsed countless scientists running for state legislative and municipal offices.

“When you think about the issues facing our world and our country – climate change being at the top of that list – there isn’t an issue that doesn’t benefit from having scientifically-minded people at the governing table, not just waiting to be tapped as advisors,” she said during the event. “It’s been a challenge because scientists assume they shouldn’t be involved in politics, but this model has really failed us.”

She and the other speakers all agreed that we have to start thinking differently about who comes to mind when we visualize an ideal politician – this goes for scientists, but also for women, young people, and people of color.

An essential part of fixing this broken model and training scientists to run for office, said Naughton, is improving their ability to communicate with the public, in particular communicating scientific uncertainties and responding to the public’s values in ways that keep their trust. I couldn’t agree more. In fact, this is the basis of my own research. It was a relief to see others understand the vital importance of science communication to sustaining democracy.

Taylor, who received training from 314 Action, has gone on to incite real change in her county, including founding a public health department and a sustainability office. “Those offices are going to be there for generations to come,” she said. While there are costs to being in the limelight, like always having to be on, even when you’re at Target, “creating this long-term change is a really big reward,” she added.

We often pay more attention to federal elections, but voting isn’t just a federal affair. Taylor’s success is a reminder that local elections can have substantial impacts on our lives as well.

Later in the week on October 17, I also attended an event with Dan Utech, the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and Director Mann on the progress the Biden administration has made in addressing climate change.

“We have to hold in our mind two seemingly contradictory facts,” said Mann at the beginning of the event, “that we haven’t made enough progress and yet at the same time that we’ve made a lot of progress.”

This sounds right to me. As Dan Lashof, Director of the World Resources Institute put it, President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is “the most comprehensive climate legislation the U.S. has ever seen.” However, “Earning top marks in climate action…will require continuing timely and equitable implementation of the legislation while taking additional action to fill policy gaps,” he added.

In addition to discussing some of the details of the IRA, Utech and Mann also discussed another Biden initiative, American Climate Corps, which aims to put young people to work to combat climate change. So far, the initiative has recruited over 15,000 people. Along these lines, Biden also set up a Youth Advisory Council at EPA with the aim of making “youth engagement a priority” in resolving environmental issues, Utech said.

Director Mann also asked Utech about federal agency responses to Hurricanes Helene and Milton and the conspiracy theories surrounding them. Utech pointed out that agencies, such as FEMA and EPA, have started to respond directly to misinformation on social media, in addition to deploying people on the ground after disasters.

“FEMA and EPA and other parts of the response are trying new things, including actively batting misinformation down as it comes into view,” Utech said.

Part of the Biden administration’s goal when putting individuals in leadership roles in administrative agencies, Utech told me after the event, was to make sure they were led by people who excelled at communicating directly with the public, both in person and on social media. This goes for EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan as well, he said, who’s probably had the most prolific social media presence of any EPA administrator.

Let’s take a second to think about the common thread that runs through both of these events. They tell a story of individuals working painstakingly hard to not only combat climate change but also the misinformation and disinformation that comes with it, both of which put people’s lives at risk. Yes, we have a lot of work ahead of us. Yes, there are others who knowingly and unknowingly are hurting this effort. But there are still a lot of us who care, who aren’t going to give up.

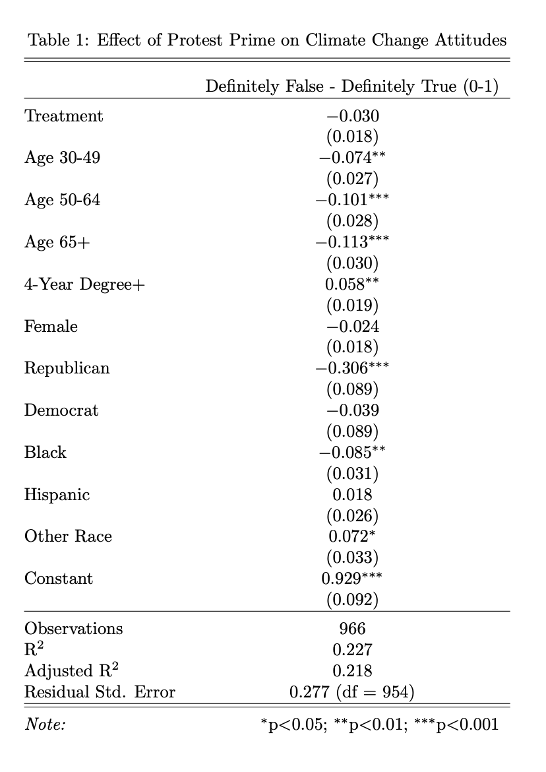

I agree with Director Mann when he said during the second event that “today the primary threat to climate action isn’t denialism, it’s nihilism, the notion that it’s too late to do anything.” While I admittedly don’t have empirical data to support this, I think it’s nihilism that drives many of us to conspiracy theories to begin with.

I want to acknowledge that I understand that temptation. In the aftermath of Helene and Milton and with the upcoming election, I feel that temptation too. Tired as we all are in 2024, still waiting for the barrage of disasters of one form or another to stop, nihilism tugs at you.

But giving in to nihilism is a choice I’m not going to make. Instead, I’m going to continue making my own contributions to fighting climate change and saving our democracy, including voting in the next election. Democracy isn’t a given. It’s something we must actively keep alive and nurture. The same goes for our planet.

As Director Mann alluded to at the end of the second event, when Benjamin Franklin was asked by a group of citizens what sort of government he and the other founders of the U.S. Constitution had created, he responded: “A republic, if you can keep it.” In other words, whether the republic lives or dies is in our hands. All is not yet lost.