Originally published by Peter Coy for The New York Times op-ed Aug. 23, 2023.

Gresham’s Law says that bad money drives out good. If you have two coins with a face value of $1, you will spend the bad one that contains 25 cents’ worth of metal and stash away the good one that contains $1 worth of metal.

Something like Gresham’s Law is at work in the carbon offset market, which was set up to fight climate change. Bad carbon credits are driving out good carbon credits. And that’s a big problem for the effort to curb the greenhouse gas emissions that are heating up the planet and wreaking havoc from the Arctic to the Antarctic.

An Aug. 16 report for clients of the British bank Barclays put a positive spin on the problem but contained some worrisome information.

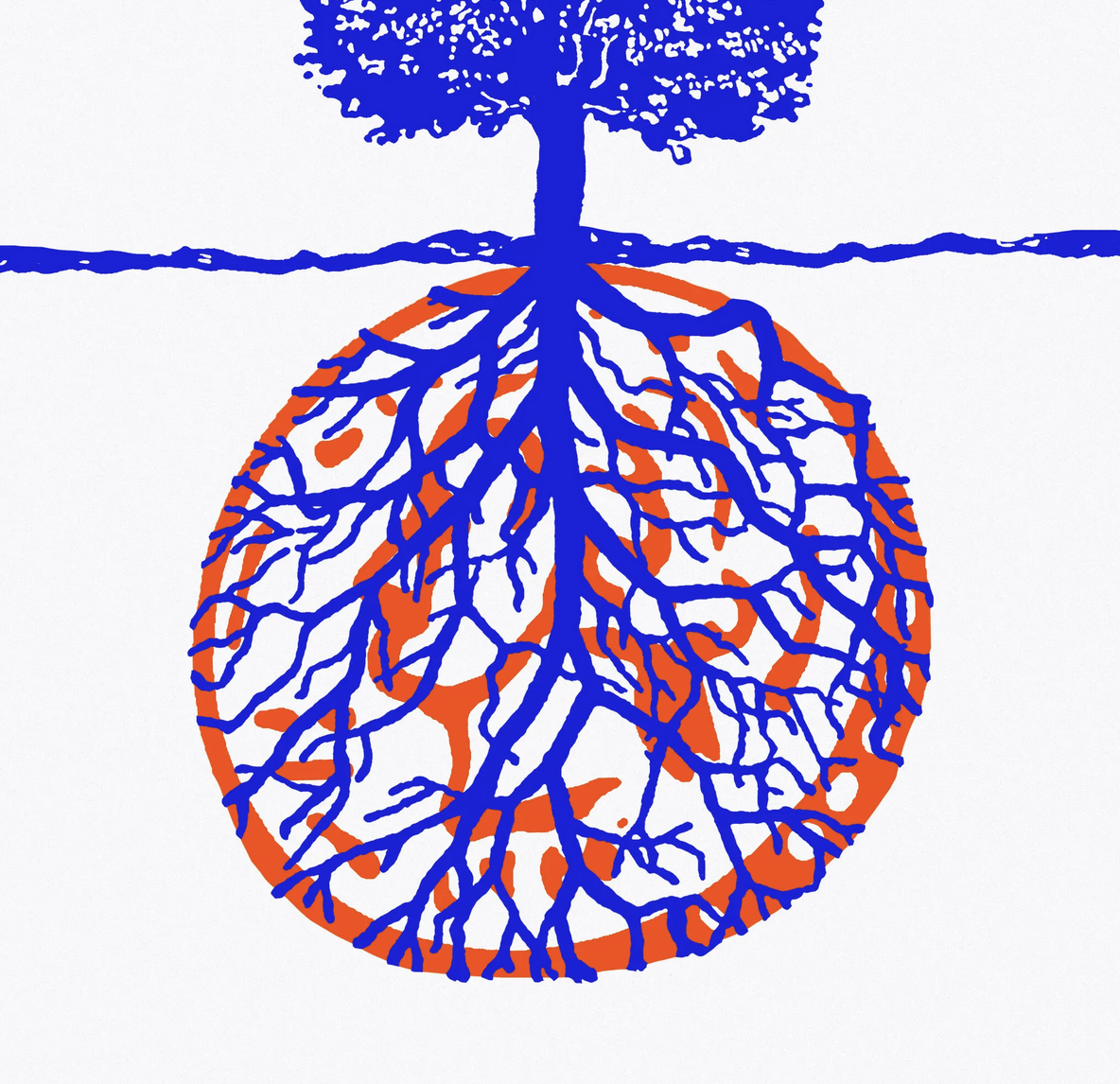

The Barclays report focused on the voluntary carbon market. That’s the one that companies such as Microsoft and Salesforce are using to help reach their goals of net-zero carbon emissions. If they can’t reduce their own emissions all the way to zero, they can go into the market and buy credits from someone in, say, Brazil who has earned them by planting trees to soak up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The voluntary carbon market can be a valuable mechanism for directing investment to developing nations that need help in the fight against climate change.

“The market will get big because we need it to get big,” Austin Whitman, the chief executive of the nonprofit Climate Neutral, told me. “We will not hit net zero without large and well-functioning carbon markets.”

Here’s the Gresham’s Law problem, though: According to the Barclays report, the price of carbon credits has fallen to around $2 per metric ton of carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere, down from around $9 early last year.

That’s not because the cost of reducing emissions is really just $2 a ton. It’s because buyers don’t trust the quality of the credits. They worry that the sellers of credits aren’t doing what they promise. For example, a seller might claim credit for stopping a forest from being cut down when there was no plan to cut it down in the first place. This is an old but vexing issue that I wrote about two years ago.

The price of carbon credits is much higher in the official, intergovernmental markets, which have stricter standards. In the European Union Emissions Trading System, the world’s liquid carbon market, the price of credits is around 94 euros a ton, or more than $100. Those official markets are how countries will comply with the Paris Agreement, a global climate treaty adopted in 2015.

Another problem with the voluntary market is double counting, in which a project that reduces emissions is claimed both by the corporation that paid for it and by the country where the work was done.

The Barclays report said that the voluntary carbon market — with its inconsistency and lack of regulation — is “undermining the Paris Agreement process by casting doubt on the legitimacy of country-level emission reductions since these are also being claimed by corporates in other countries.”

The Barclays authors expressed pessimism that the problem could be fixed through negotiations between the rich countries that need credits and the poor countries that tend to sell them. They described as “relatively unlikely” the possibility that an official market for trading carbon credits could be “operationalized” under Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement, which covers international trading of credits.

What might happen instead, the Barclays authors wrote, is that the voluntary, unofficial market could expand spectacularly, from $500 million now to $250 billion in 2030 and as much as $1.5 trillion in 2050. That is frankly hard to imagine. To put it in perspective, it would make the market 500 times as big as it is now in just seven years and 3,000 times as big by 2050.

For the Barclays forecast to come true, confidence in the voluntary market would have to be restored. That would require some form of regulation to combat Gresham’s Law, either by governments or by the participants themselves. But why would participants in the voluntary market be able to build a well-functioning international market if governments can’t?

“This is the bombshell that no one understands,” Joseph Romm, a physicist who works on climate-change policy, told me. Romm is a senior research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania Center for Science, Sustainability, and the Media, where he recently wrote a paper asking whether carbon offsets are “unscalable, unjust and unfixable.”

Rather than growing, as Barclays envisions, the voluntary carbon market ought to be folded into the official market and disappear. There should be a single, unified global market with a single price. That’s the only way to keep Gresham’s Law from doing damage. “It should be reasonably clear that you can’t have two different markets in a world that’s seriously trying to go to zero,” Romm said. “Somebody has to do the official accounting.”

A separate carbon market for voluntary projects made sense in the early years of fighting climate change at the corporate level, when any kind of effort was better than nothing. But it should be a second-best solution now that all countries have ostensibly committed to reducing their carbon emissions, Mark Kenber, the executive director of the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative, told me.

“The fact that we are in 2023, some 35 years after international negotiations started, still talking about voluntary action is a sign that we have collectively failed,” Kenber said. He said “the voluntary carbon market is filling a gap that shouldn’t exist” — but added that in the interim, it can play a role in “cutting emissions and channeling finance where it’s needed most.”

Elsewhere: Less Crude for Emergencies

There are about 23 million fewer barrels of crude oil in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve now than there were in January, when I wrote that the drawdown, which was aimed at holding down prices of gasoline and other refined products, “looks scary.” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm told CNN in July, “The bottom line is we are going to replenish.” But the replenishment is likely to take years and may never restore the S.P.R. to its 2010 peak, when it held twice as much crude as it does now. Congress, concerned about deficits, will be loath to spend a lot of money buying oil, especially if the price seems high.

On the bright side, a big strategic reserve isn’t as important to the United States as it once was because the United States is less dependent on imports. Also, oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, which are vulnerable to hurricanes, account for a smaller share of production. “Don’t worry about refilling the caverns too quickly,” Julian Lee, an oil strategist for Bloomberg, wrote last month.

Quote of the Day

“At the end of 2022, less than 1 percent of all deposit accounts had balances above the deposit insurance limit of $250,000 but accounted for over 40 percent of banking industry deposits.”

— Martin Gruenberg, chairman of the F.D.I.C., in a speech on Aug. 14, 2023

Peter Coy has covered business for more than 40 years. Email him at coy-newsletter@nytimes.com or follow him on Twitter. @petercoy