Originally published by Frank Kummer for The Philadelphia Inquirer on November 20, 2023

Mann, of the University of Pennsylvania, and Socolow, of Princeton, were named 2023 John Scott Award winners.

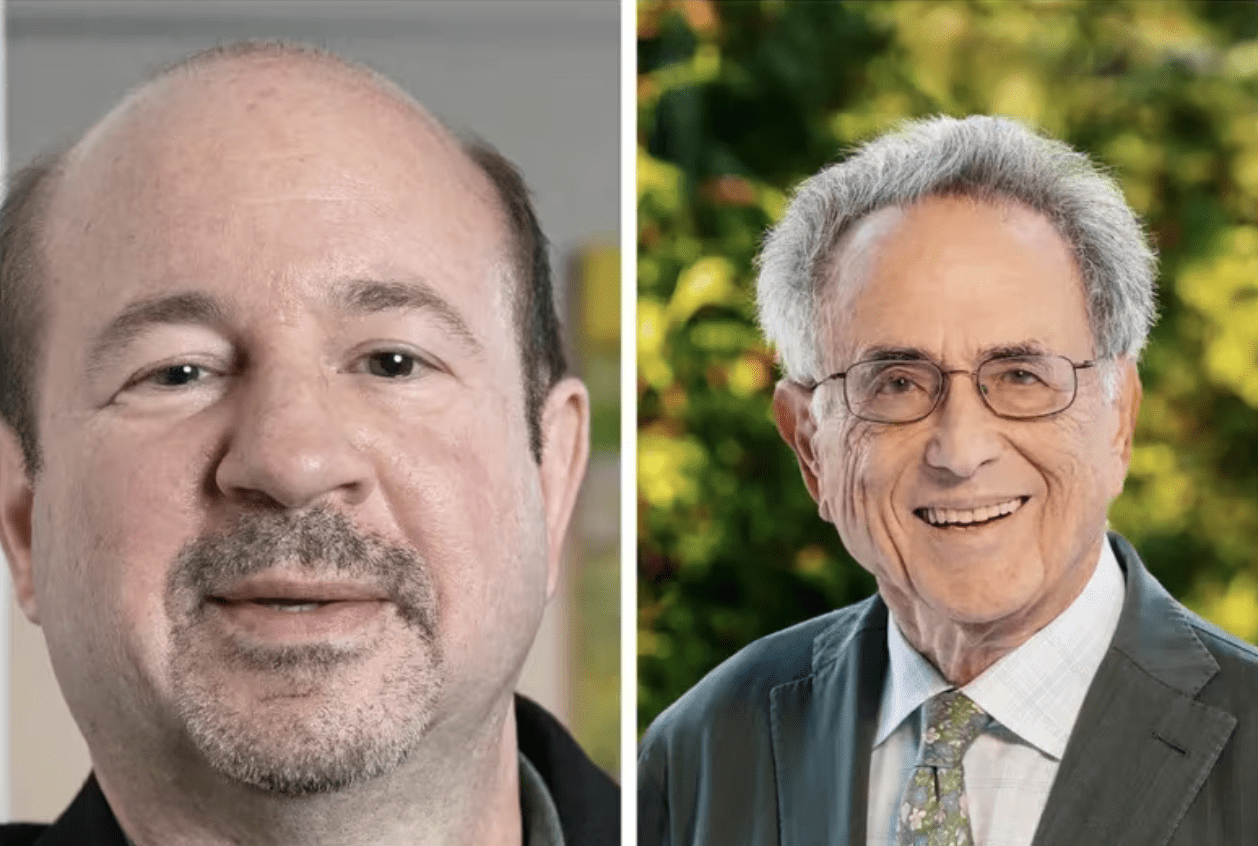

Michael Mann of the University of Pennsylvania (left) and Robert Socolow of Princeton University are winners of the 2023 Scott Awards.

Michael Mann, a nationally recognized climate scientist at Penn, notes that Benjamin Franklin charted the Gulf Stream, launched complaints against tanneries polluting Philadelphia’s Dock Creek, and studied weather patterns.

Maybe it’s a bit of kismet then that he’s one of two scientists, along with Princeton’s Robert Socolow, named as winners of the 2023 John Scott Awards. The prestigious awards are named after the 19th-century chemist who endowed the prize in honor of Franklin.

“The award means a lot to me,” Mann said, “because it reflects sort of the legacy of Benjamin Franklin. He was an environmentalist. You could even argue he was an early climate scientist and a climate advocate.”

The awards this year focused on climate change, “recognizing the growing urgency worldwide to address the crisis of global warming.” Mann and Socolow will be presented with their awards Nov. 30 at the American Philosophical Society, founded in 1743 by Franklin in Philadelphia.

The award comes with a prize of $15,000 each. Winners are selected by other scientists from around the nation. The awards are administered by the Board of Directors of City Trusts, a group that manages dozens of charitable trusts for which the City of Philadelphia has been named as trustee.

Michael Mann: ‘Sticky’ myths

Mann, 57, is a presidential distinguished professor in the department of earth and environmental science and director of the Penn Center for Science, Sustainability, and the Media at the University of Pennsylvania. He was long associated with Penn State, until he took the job at Penn in 2022.

Mann became widely known in climate science after the 1999 publication of his “hockey stick” graph, which showed earth’s average temperature had been mostly stable for 1,000 years until 1900, when it spiked sharply up. His latest book, Our Fragile Moment: How Lessons from the Earth’s Past Can Help Us Survive the Climate Crisis, seeks to show how conditions that allow humans to live on this earth are incredibly fragile.

Mann, who has strong family connections to Philadelphia, said he’s glad he made the move in 2022 to Penn, where he focuses not only on climate science, but also on how to reach the public on misinformation that spreads so quickly on cable TV, the internet, and social media.

“My view is that the debate over the science has really moved on,” Mann said. “Obviously there’s a denialist fringe out there. But the debate has moved away from denial because that position is no longer tenable. It’s about division and distraction.”

He’s teaching a joint course in the spring with Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center, on the challenges communicating about climate and environment. He refers to new media, which includes social media, as “the Wild West,” where misinformation about climate science spreads virally.

“It’s sort of fun for me to be bringing together communication students and science students in the same class,” he said. “I think the interaction will be very interesting.”

Mann said myths are often offered up as facts, creating a “stickiness” that’s hard to dislodge.

“So if you’re trying to educate people, you first have to dislodge the misconceptions that have been driven by a concerted misinformation campaign,” Mann said. “One of the rules is that you’ve got to replace that misconception with something that’s just as sticky, just as memorable.”

» READ MORE: Mann: Ben Franklin was a climate activist, perhaps America’s first

Robert Socolow: Common ground

Socolow, 85, professor emeritus in the department of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Princeton, is recognized for his research on climate and environmental science. With a focus on carbon management and energy use, his work led to creation of a partnership between Princeton and industry — the Carbon Mitigation Initiative (CMI). Socolow, known for seeking middle ground in a solution to climate change, retired in 2019.

“It’s an amazing honor,” Socolow said of the award. “I just feel deeply grateful that this goes back to a person who admired Benjamin Franklin. That still sends chills down my spine. You certainly don’t imagine this kind of recognition.”

Socolow said he’s honored to be among his predecessors, which counts 20 Nobel Prize winners, most recently, 2023 Nobel laureates Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman, of Penn, for their breakthrough into mRNA research.

Socolow said he’s been interested in climate change for 50 years. But addressing it, he said, will cost money. He cited the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts of the 1970s as an examples of how government can tackle big environmental problems.

“When we when we cleaned up the air, it cost money to do that,” Socolow said. “We did a rather extraordinary job.”

Socolow said he’s interested in an approach that builds alliances so that most efforts are spent collaborating “not fighting each other.” He’s led the CMI’s research into how to capture carbon dioxide that’s released by burning fossil fuels.

He said the oil and gas industry has impeded progress on climate change, which he hopes can be addressed at COP28, the United Nations Climate Change Conference to be held starting Nov. 30 in Dubai. Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, the United Arab Emirates president of COP28, has urged attendees to seek “common ground” over the future of fossil fuels. Al Jaber is also CEO of Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. It’s the first time the U.N. has named the head of a fossil fuel company to run COP.

Socolow coauthored a recent Washington Post commentary he hopes can be discussed at COP28. The piece calls for transitioning away from fossil fuels in the next few decades. After the transition, fossil fuels would only be allowed for a use if carbon dioxide would not end up in the atmosphere. Remaining carbon dioxide could be captured and stored under ground or converted into products in a circular system, he wrote.

“I was, from a very early age, encouraged to think globally about our role as human beings on the planet,” Socolow said, ”and that we had a common fate that transcended nations.”