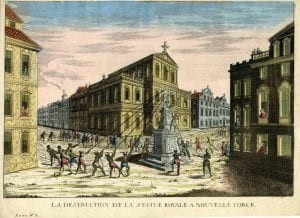

The American Revolution was a world event. All of Europe and its colonies were interested in what happened in the North American colonies. French authors and journalists published extensively on the conflict. Consequently, there is a huge corpus of printed materials and archives in continental Europe that scholars are currently exploring to better understand the intellectual, political, economic, and diplomatic aspects of American Independence. In addition, the presence in France of major American figures such Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson, as well as other less well-known American agents such as merchants and sailors makes it necessary to include the French side of the story in the narrative of the American Revolution. The interactions between Americans and French intellectual, diplomatic, and economic figures also contributed to the definition of American identity. Therefore, I believe that French scholars working on the American Revolution complement U.S.-centered understandings of this event by moving the focus away from the Britain-U.S. perspective. Their work also reminds historians that relations with France were not peripheral to the American Revolution and went beyond the folklore that has come to surround the Marquis de Lafayette.

Studying the American Revolution from the vantage point of a country that has a rich revolutionary tradition of its own has both advantages and drawbacks, however. Because of the French Revolution, French scholars may be more sensitive to the universal meanings of the American Revolution, and they also must acknowledge that the first modern anti-monarchical revolution took place in the U.S. rather than in France. They also have to take stock of the fact that the U.S. invented many of the modern political forms that are still favored by Western democracies, including declarations of rights and written constitutions and conventions. To some extent, the comparison between these two revolutions and the motif of the sister republics still hovers over such studies. The post-Atlantic-Revolutions era of scholarship may have arrived, but the question of the potential “influence” or connection between the American and French Revolutions continues, consciously or not, to influence how scholars study the Age of Revolutions, as the historical sequence of these events still bewilders both French and American scholars.

My own work on French reception of printed works (books, newspapers, and visual representations) pertaining to the American Revolution in the 1770s and 1780s fills a historiographical gap and helps to answer some of the questions raised by the still undecided issue of the connection between the French and American revolutions. It also contributes to our understanding of how ideas circulated in France and between France and the U.S. at key moments in the history of both countries (the end of the Ancien Régime in France and the creation of a republic in the U.S.). The American Revolution brought the topic of colonialism to the foreground of French politics just as debates about French institutions were becoming more central. The French then brought these anti-colonial, anti-aristocratic, and anti-monarchical threads together from 1789 onward. So, on the French side, revisiting French understandings of the American Revolution before the French Revolution may help us better situate our own revolution as well.

Carine Lounissi is Associate Professor of American University at the University of Rouen-Normandy. Her research interests are late eighteenth-century intellectual history and more specifically transatlantic intellectual cooperation and debates during the Age of Revolutions. She has published two books on one of the major figures of these transatlantic circulations, Thomas Paine. The most recent one, relying on new sources and archives by and about Paine, is titled Thomas Paine and the French Revolution (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). Her current project is devoted to the reception of the American Revolution in France from 1776 onward. She is assistant editor of the Thomas Paine Papers to be published by Princeton University Press in 2025 and a member of the steering committee of the AMERICA2026 project coordinated by Bertrand Van Ruymbeke.

Read Lounissi’s freely accessible article “The Impact of the American Revolution on French Anticolonial and Antislavery Views in the 1780s” in EAS’s Winter 2024 issue.