Jaime Lannister and the Stage Coach Dilemma

Warning: Possible spoilers for those reading or watching Game of Thrones. If you’re up-to-date with the television series, then nothing in here will spoil anything. If you’re not, then you probably don’t want to read further. Also, if you’re going to get frustrated with Game of Thrones references, you also might not want to read this one. – RK

Paarfi of Roundwood [to the camera] We’re here today with Jaime Lannister, son of Tywin Lannister. Jaime, more commonly known as the Kingslayer, has agreed to this short interview, for which we are of course both honored and grateful. [Turning to his guest] Greetings, Kingslayer…

Jaime Lannister: Please, call me Jaime…

PofR: Oh, such a presumption would be the height of insolence…

JL: You didn’t let me finish. I was saying, “Please, call me Jaime, or I will end you.”

PofR: Ah. Yes… Right, then, Jaime. Again, I greet you, and thank you for taking the time for this interview.

JL: Of course.

PofR: Let’s get right to it.

JL: Let us.

PofR: Indeed. Here is my first question. It has recently come to our attention that you’re regicide was, in point of fact, done in the service of a greater good, preventing the immolation of King’s Landing on the orders of the mad King Areys. As is now well known (to viewers), the King would have laid waste to the city had you not killed him instead of protecting him, as was your sworn duty. Yet you have allowed yourself to be branded oath-breaker and, in many circles, scoundrel. Why have you not let it be known that the act for which you are most famous was in fact a piece of moral nobility rather than villainy?

JL: Ah, my dear Paarfi. While your gift with the quill is unmatched… [Parfi bows low at the compliment]… you have let yourself become confused regarding an important matter of diction.

PofR: Indeed?

JL: It pains me to say it, but you have. You see, what I did might, I suppose, have been called “noble,” but it was in no way “moral.” I can explain in two words. I won’t bore you with recounting the well-known “Stage Coach Dilemma”…

PofR: …in which people judge it morally wrong to throw the knave with the extra-large broadsword on his back off the rock outcropping to stop the horses from trampling the unsuspecting five squires in the horses’ path…

JL: …which illustrates that one must be careful to distinguish acts, on the one hand, that lead to the achievement of the greater good from, on the other hand, acts that fit our ideas about what is “moral.” From this we see that achieving the greater good and acting morally are in no ways synonyms.

PofR: Ah, I see. So your act was, let us say, “altruistic,” producing benefits to many, but immoral, violating a moral rule. Well, several rules, actually…

JL: Just so…

PofR: And how has the immorality of the act affected you?

JL: How can you ask? In the usual way… That is [Jaime sighs]… everyone is against me.

PofR: Well, not everyone…

JL: Well, true. You know, before the war broke out, feelings were mixed. Some were willing to overlook my deeds because, well, otherwise I might do violence unto them. And, by and large, close family members of mine were willing to overlook my immoral actions… Still, the prevalence of the moniker kingslayer, was in many circles not intended as a compliment. Then, with the war, coalitions and alliances, as you know, matter a great deal more than the details of who killed whom… So, now most people – especially lions and our allies – are willing to overlook my history with respect to a certain immoral – but, as you say, possibly noble – act.

PofR: Well, not all immoral acts are created equal…

JL: Have a care, my young friend…

PofR: Well, I am in no ways young, but let us pass on to this next issue. Let us speak, perhaps, only in hypotheticals…

JL: As long as we confine ourselves to them…

PofR: Suppose that you had, ah, close personal relations with a blood relative…?

JL: If you mean [unprintable] then just say [unprintable]!

PofR: Yes, just so. If you had had those sort of relations with your sister, Cirsei… which, I hastily add, is somewhat understandable given that you spent a part of your junior years away from her at… Crakehall with Lord Sumner, if I have it right…?

JL: You do…

PofR: Well, we have it on good authority that living apart from a close relative – especially a close relative with the sorts of charms possessed by your twin sister – can cause even the noblest of us to, shall we say, become quite helplessly ensorcelled…

JL: You have no idea…

PofR: And yet, here we have something of a seeming contradiction. Your father Tywin seems very pleased to let pass oath-breaking regarding the slaying of kings while you were sporting the white cloak, and yet here, in this hypothetical, why, here it seems he is disinclined to let matters pass, taking the moral – that is, moralistic view of the matter – as opposed to showing loyalty to his son. So, to summarize, in the king-slaying case he seems to choose kinship and loyalty over the moral rule, yet in the – yes, hypothetical – incest case, he chooses the weight of the moral rule over kinship. Is it not a puzzle?

JL: [laughs] Only if you don’t know my father. He is quite content to let a little oath-breaking go by when it serves his interests. But remember that if the three royal offspring were known – or thought – to be mine rather than those of the former king, Robert Baratheon, then they would lose claim to the line of succession. In short, he cannot support any supposed moral infraction I committed in this respect because to do so would compromise his self-interest in terms of maintaining the Lannister line of succession. To put it bluntly, he chooses loyalty over morality when it serves his purpose, and morality over loyalty when it serves his purpose. In this way, we can see, that one’s moral condemnation of others should be understood as a means to pursuit of interest, and easy to shake off when they ill fit the situation.

PofR: Well, that is one way to look at it, and, if I might, a most cynical one.

JL: Perhaps. Yet there are important lessons here of which you might want to take note. First, and perhaps foremost, while people sometimes use morally relevant actions in deciding whose side to take in conflicts, they do not always. Morality can be trumped by kinship and the exigencies of the moment…

PofR: Stay… that phrase, ‘the exigencies of the moment.’ I confess I like its sound.

JL: I’m honored that you do. [Jaime makes a barely courteous bow] From this we see that the claim that “kinship” and “loyalty” are types of morality are mistaken. These two are forces that work against morality, which is by its nature impartial. And, further, to bring things back to maters of interest to us, this lens, though you call it cynical, is an apt one through which to see many of the dilemmas faced by the characters, er, I mean, the participants in the politics afoot in Westeros. For instance, what is a man of the Night’s Watch to do if he can bring about the greater good only by betraying his oath of celibacy? And once he is foresworn – in the interest, be it understood, of the realm – should he be judged guilty and punished, or celebrated for the lives he has saved, as our poor soul in the Stage Coach Dilemma? To return to my case, suppose you grant that my choices and actions saved the good people of King’s Landing. Should I nonetheless be punished for oath-breaking and regicide? Or rewarded for saving those many lives of the little people?

PofR: I was under the impression I was to be asking the questions in this interview…

JL: And I was under the impression there would be mead in the green room.

PofR: [Paarfi shifts nervously] Are there other examples from the recent history of Westeros that illustrate these principles of which you speak so fondly?

JL: To be sure. But, come, let us leave such musings to the viewers, which will doubtless give them many hours of pleasant contemplation.

PofR: [turns back to the camera] And so, with those thoughts to ponder, we are pleased to be Paarfi of Roundwood… Until next time.

[fade to black]

Full Time Research Assistant – Kurzban lab at Penn

I am currently seeking a full-time, paid research assistant to work in my laboratory in the Department of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, PA, starting on August 15th of this year, continuing for two years. In exceptional cases, I will consider a one-year commitment, but those who are able to commit for two years will be given preference. The position entails taking operational leadership of an ongoing United States Air Force funded project investigating the evolved function of revenge. Responsibilities include recruiting participants, managing the data-to-day operations of the experimental sessions, and managing one part-time undergraduate research assistant who helps to run experimental sessions. This position is probably best for someone who is interested in gaining experience in an experimental evolutionary psychology laboratory with the goal of eventually applying to graduate school in the area. The position is for two full years, and pays $28,500 plus benefits.

To apply, please send me (kurzban@psych.upenn.edu) a cover letter indicating your qualifications, a c.v. or résumé, and names and contact information of three potential references. (Please note that the successful applicant will also have to apply through the more formal channels through the University of Pennsylvania.) For best consideration, please submit your application by May 31st.

The Power of Prayer

I was lucky enough to have a chance to visit some friends and colleagues in Denmark – partially explaining why I didn’t manage to get a new post up last week – and I’m writing this on my return trip, which happens to have been on a day called “Store Bededag,” or Great Prayer Day, a holiday unique to Denmark (and, according to Wikipedia, the Faroe Islands). The Danes I spoke to about Great Prayer Day seemed to think that few people in Denmark did much in the way of actually praying on Great Prayer Day – unlike, he added in awkward transition – the people who are the topic of my post today, Herbert and Catherine Schaible, of my own current home and destination, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

You might have read about this story already because it was reported in some national news outlets because the Schaibles killed a second child with their prayers. Or, that’s one way to put it. Back in 2009, one of the Schaible’s offspring contracted a case of pneumonia. The Schaibles belong to a religious organization that holds that it is morally wrong to “trust in medical help,” so, instead of committing the sin of getting treatment for their child, they prayed, with the foreseeable effect that the child, Brandon, died. Although it seems easy to argue that the parents caused the death of their child – (“but for” their inaction, the child would be alive today) – the Schaibles were given the comparatively light sentence of probation.

Last week, it was reported that the Schaibles, presumably not wishing to commit the sin of treating their child, caused the death of another child, this time from what has been described as “diarrhea and breathing problems.”

I have a few points that I thought I would make about this story, though I find it impossible not to begin by saying that I find it deplorable that the criminal justice system in the United States found probation appropriate punishment in the case of Brandon’s death. (There were a number of interesting comments on the pages of sources reporting the story, many along the lines of suggestions that the Schaibles should be jailed without food or water, but permitted to pray as hard as they wished for supernatural room service.)

Keeping you dry… and happy!

Why was the punishment so lenient? I haven’t studied the prior case, but I can say something about some relevant moral intuitions, which are to some extent reflected in American law. Three come to mind. First, their choice to do nothing was based on a false belief, that praying has effects. Under certain conditions, people find having certain false beliefs exculpatory. (I’m sure this is what the person who currently has my umbrella would say if pressed on what she’s doing with it. Our two umbrellas did, I concede, look similar, which is why I’ve resumed carrying around my Mickey Mouse umbrella. Fashionable, maybe not, but more distinctive than plain black, yes indeed.) Second, the Schaible’s choice to do nothing was based on a moral belief, that applying medical treatment is wrong, though I’m not sure the precise role that moral belief played in the legal transactions. Finally, and probably most importantly, their choice was an omission, as opposed to a commission. For reasons that are still the subject of debate in the relevant literature, holding everything else constant, including intentions and outcomes, people judge omissions as less morally wrong than commissions.

The case makes me think about proposals regarding the function of morality. Take, for instance, Jon Haidt’s well-known work. One function of morality, he has argued, is to facilitate helping kin. He makes this explicit, writing that one function of morality is to “protect and care for young, vulnerable, or injured kin” (Haidt & Joseph, 2007). Cases such as this one are somewhat peculiar, given this view, since it was morality that caused them exactly not to “protect and care for injured kin.” This is consistent with what I and some of my collaborators have found in some experimental work. Morality frequently works against the goal of aiding relatives. If moral judgments are (in part) for helping kin, it seems to botch the job on at least some occasions.

A second thing that this case makes me think about are various proposals about the benefits of false beliefs. I don’t doubt that there are certain benefits to having certain false beliefs. On the other hand, such arguments must, in my view, run uphill. As I’ve written about (at possibly too much) length elsewhere, generally it’s good to have true beliefs, and bad to have false beliefs. Here is a good example of the (very high) cost of a false (supernatural) belief, and such cases I think should be borne in mind when proposals regarding the benefits of false beliefs are made. Whatever their benefits, false beliefs carry costs as well.

And then there is the key issue of omissions. The intuition that omissions aren’t, somehow, so bad, is a strong one. It really doesn’t seem as bad to fail to act compared to acting in a way that leads to the same outcome. The philosopher Peter Singer has tried to push back against this intuition using the typical tool of philosophers, thought experiments. Suppose a baby was about to drown, and you could only save her by wading into the water, ruining your fancy shoes. Would you do it? Not only are your intuitions telling you that you should, but they are also telling you that someone who didn’t was the worst kind of soul.

The principle is that you shouldn’t fail to take an action that is costly if it will save a life. Or, further, that it’s wrong to fail to act if one can to endure a cost to save a life. This principle seems all well and good except, Singer argues, it leaves most of us with a problem. Every day, all of us lucky enough to live in the industrialized West could, if we wished, donate money to a charity that could use the money to save a child’s life. Each time each of us spends money on a dinner out instead of such a charity, we are making the choice equivalent to refusing to save the drowing child. (To his credit, for Singer, these are more than thought experiments. Taking his own line of argument seriously, he practices what he preaches, and gives a quarter of his income to charities that save lives. I don’t usually put media in here, but I’ve tried to put his short video below:)

Am I trying to draw a moral equivalence between dining out instead of donating to child-saving charities and the Schaible’s reprehensible behavior? Only a faint one. Parents have duties and obligations to children. Few would deny this. Individuals’ duties and obligations to our fellow humans is at least arguable, though of course people like Singer argue, correctly, I think, that this is an argument worth having.

To close by returning to the scientific issue, why do we find omissions less morally wrong than commissions? If morality were designed to increase social welfare, one might have thought that our moral intuitions would have been that failing to help others (a lot) at (small) costs would have been seen as among the most morally reprehensible things one might do. The criminal justice system’s response to the Schaible case suggests that we’re surprisingly lenient when it comes to (deadly) omissions.

References

Haidt, J., & Joseph, C. (2007). The moral mind: How 5 sets of innate moral intuitions guide the development of many culture-specific virtues, and perhaps even modules. In P. Carruthers, S. Laurence, and S. Stich (Eds.) The Innate Mind, Vol. 3. New York: Oxford, pp. 367-391.

Singer, P. (1972). Famine, Affluence, and Morality. Philosophy and Public Affairs, vol. 1(3), pp. 229–243

What We Have Here is a Failure to Replicate

On Monday of this past week, Hal Pashler gave a talk as part of the Psychology Department’s colloquium series at my home institution, the University of Pennsylvania. His talk focused on the issue of replication in certain areas of experimental psychology. Some readers might recall something of a stir in the blogosphere when Doyen et al. reported a failure to replicate work that looked at whether priming people with words related to old age, such as “bingo,” and “Florida,” caused people to walk slower than those not primed with such words. Pashler discussed some work that he and his colleagues also published in PLoS reporting their attempts to replicate related studies showing that subjects who plotted points closer together experienced feelings of greater closeness to their families relative to subjects who plotted points further apart. I’ve put the results of the closeness study here in the Figure below. In his talk, Pashler discussed a number of other attempts to reproduce results of this general type, all with the same result: a failure to replicate.

Figure from Pashler et al. (2012). Ratings of closeness by condition.

The topic of replications has been discussed at some length, and I’m not in a good position to contribute anything substantive to this discussion, but I thought I would spend a few moments musing about the topic for a few reasons. First, there’s a new paper (paywall) by Ioannidis & Doucouliagos “What’s To Know About The Credibility Of Empirical Economics?” Holding aside their rather dismal evaluation of the dismal science — “the credibility of the economics literature is likely to be modest or even low” – I particularly liked the way the authors quite dryly expressed the general problem: “Replication is a public good and hence prone to market failure.” The footnote this with a reference to Dewald et al. (1986), who wrote: “A single researcher faces high costs in time and money from undertaking replication of a study and finds no ready marketplace which correctly prices the social and individual value of the good.”

Pashler had a great slide, a picture of a passage from a second grade textbook, telling the (young) reader that a cornerstone of science is replication. Given how rarely research is, in fact, replicated in many areas of science, the point is well taken. Which is not to say that there aren’t efforts being made to try to address the problem, including, for instance, the Reproducibility Project and Psych FileDrawer.

Discussions of why replications aren’t more common – including Pashler’s remarks – focus extensively (but not exclusively) on incentives. If a researcher attempts to do an exact replication of published work, there are two possible results. If the result replicates successfully, it is likely to be difficult to publish because journals tend not to publish replications, though this is changing. Last month, for example, Bobbie Spellman announced an initiative at her journal, Perspectives on Psychological Science, providing an interesting mechanism for publishing replications. Other journals are proving more receptive to publishing replications – and failures to replicate – which will probably have some beneficial effect. In any case, my guess, though I don’t know, is that replications of results are cited relatively infrequently, especially compared to the original results. Publishing failures to replicate is likely no easier than publishing successes.

The issue of incentives does not, of course, end with authors. One issue that the editorial team at Evolution and Human Behavior is discussing is what our policy ought to be in this regard. While I myself feel that the sort of Registered Reports that PoPS is soliciting have tremendous value, what will the effect be on the journal? There is little use denying that in the present era, journals – and their editors – are judged on quantitative metrics, especially citation counts. To the extent that replications, successful or not, draw fewer citations than new research, publishing replications entails a cost to the journal, exactly along the lines of the Dewald et al. quotation above: publishing such papers is enduring a cost to produce a public good.

If its’ true that publishing replications reduces the infamous impact factor – as well as other metrics – authors are affected as well. At many institutions, departments and personnel committees use metrics such as impact factor to evaluate the quality of the journal that candidates up for promotion are publishing in. Would contributors to particular journals be willing to pay the price of the reduced impact factor to support a policy of publishing replications?

This is not, exactly, a rhetorical question. I’m interested in the question of whether members of the evolutionary psychology community believe that E&HB should encourage/tolerate/permit the publication of replications and failures to replicate. (Please feel free to contact me offline. No need to make your thoughts public unless you want to.) I should note a couple of points. First, the journal doesn’t receive many replications, successful or otherwise. Second, I recently green-lighted a paper that was as close to a replication as one can do, given that the study was executed in a very different context from the initial study. So, there is a sense in which the journal is already in the business of publishing replications. Should it be?

Citations

Dewald, W.G., Thursby, J.G. and Anderson, R.G. (1986) Replication in empirical economics. The Journal of Money, Credit and Banking Project. American Economic Review 76: 587–603.

Doyen, S., Klein, O., Pichon, C. L., & Cleeremans, A. (2012). Behavioral priming: it’s all in the mind, but whose mind?. PLoS One, 7(1), e29081.

Pashler, H., Coburn, N., & Harris, C. R. (2012). Priming of social distance? Failure to replicate effects on social and food judgments. PloS one, 7(8), e42510.

Ioannidis, J., & Doucouliagos, C. (2013). What’s to know about the credibility of empirical economics? Journal of Economic Surveys.

Announcement: Cooperation and Conflict in the Family Conference

This announcement comes to you via Rob Brooks. As always, please feel free to send me your announcements for upcoming events or advertisements for open position. – RK

The Cooperation and Conflict in the Family conference will be held at UNSW in Sydney, Australia from February 2-5 2014.

Post-doc Positions – University of Lyons

This announcement comes from Pascal Boyer. If you have announcements for position in evolutionary psychology or related fields, please feel free to pass them along to me for posting. – RK

Announcing two post-doctoral positions in evolutionary psychology or social psychology or cognitive anthropology.

Two post-doctoral positions at the University of Lyons, France, starting September 2013. Each position is for two years. This is to work on a project directed by Pascal Boyer on “Evolutionary and cognitive background to threat-detection and safety in modern environments”. You can find more details on the project by perusing a summary of the grant proposal.

Candidates should have pursued research in evolutionary, cognitive or social psychology, or cognitive anthropology, with a focus on one of the following domains: [a] inter-group and coalitional relations or [b] threat-detection and safety. Knowledge of French is not required.

For further information, write to pboyer [at] artsci.wustl.edu.

Zombies and Zahavis

Over the past weekend, I participated in a Zombie Run. This is relevant to evolutionary psychology. Wait for it…

Rob Zombie.

Here is the way the Zombie Run works. There are humans, and there are zombies. Humans run the 5k course with three balloons that are attached to belts. (I am pictured here with one balloon.) Zombies – people dressed up for the part – are scattered along the course, and their goal is to pop the balloons on the belts of the human runners. When all three balloons are gone, the human is “dead.” Humans, of course, try to finish the course with as many balloons left as possible, but having even one left means you survived.

(Note: humans with three popped balloons do not become zombies, as, in some sense they should, given traditional zombie lore. If that were the rule, and “dead” humans became zombies, I’m pretty sure that everyone would be a zombie by the end of the course because zombies would be proliferating so quickly. Anyway, if you lose your last balloon, you just finish the race, and by and large the zombies just leave you alone. This actually introduces a strategic element insofar as a “live” human with a balloon in the small of their back might be mistakenly taken for dead by zombies, making dodging them easier.)

Start of Zombie Run, Philadelphia

At the start of the race, humans inflate their three life balloons and attach them to their belts. And here’s where the relevance to evolutionary psychology comes in. Popping a big balloon is easier than popping a small balloon. The large balloons extend out further from the runner’s body, making them easier to grab. They are also more difficult to hide; small balloons were occasionally obscured by runners’ arms or clothes. And, of course, larger balloons are stretched out more, so they are thinner.

There were no rules, as far as I found, regarding how far you had to inflate your balloons. Indeed, I saw some runners with some anemically inflated balloons, drooping limply from their belts. Most runners inflated their balloons to a middling size. (You can see some of them in this image from the start of the race.)

As I continued to race, I noticed a few people had inflated their balloons to the extent that they were noticeably larger than others. And then I saw a balloon inflated so large it must have been near to its natural popping point, which seemed puzzling at first. Why make your balloon so easy to pop? And that, of course, reminded me of passages in The Handicap Principle by Zahavi and Zahavi, such as this one, about a predator, in this case a merlin, trying to catch a prey item, such as a skylark:

Rhisiart found that when the skylark sings while fleeing, the merlin is likely to abort the chase. When the lark does not sing, the merlin is more likely to continue the pursuit and is often able to catch the lark.

What could be the connection between the song and the chase? If we assume that some larks are faster than the merlin and some are slower, it makes sense for the merlin to try to select and chase individuals it can overtake. It is also in the interest of a skylark that flies faster than the merlin to let the merlin know that it cannot be caught. To convince the merlin of its superior abilities, the skylark must do something that a slower lark would not be able to do. Singing while flying is a good indicator of the lark’s abilities, since it displays the bird’s capacity to divert a part of its respiratory potential while still flying at least as fast as the merlin. A skylark that needs every ounce of strength it has to fly cannot sing at the same time. (p. 8).

I should say that I was unclear of the rules and details of the zombie run until I ran into the first pack of zombies. Would they have pins or sticks? Tools of any kind? Were they governed by rules? It turns out that zombies have to use their bare hands, but otherwise seemed to use whatever strategies they wished. Some zombies just stood around. Others were Defensive Back Zombies, who behaved like we were playing flag football and the runners had the ball. There were Stealthy Zombies, who jumped out from behind trees or other features on the trail. The worst were Pursuit Zombies, who would get in your way enough to make you dodge or sprint, wait a beat, and then turn to pursue you as you slowed down. (This is how I lost two of my three life balloons, both to a single Pursuit Zombie.)

This all had to be learned on the course. What I’m saying is that one possibility is that some people inflated their balloons without really knowing the disadvantages of having big balloons. Maybe.

But another possibility is that runners were using big balloons as a signal. Not, I think, to zombies, though my sense was that zombies took the big balloons as a particular challenge. I think that the signal was to other runners. In the same way that skylarks sing to signal their condition, I think big balloons are saying, hey, I can protect my life balloons from zombies even though they are big and easy to pop. As many readers of this blog will no doubt know, signals have value beyond the predator/prey dynamic above. Handicaps are also useful for signaling to rivals and, especially, mates.

So, for those of you teaching about signaling theory, this might be a nice example to use in class. It seems very intuitive to me, and students, generally, like examples to do with zombies, or really any of the undead, I find.

(Another aside. Runners quickly learn that there is safety in numbers. Being alone makes a runner very easy prey for zombies, who tend to be in little packs. People naturally in this environment reinvent herding as predator defense.)

There are zombie runs across the country. I’d like to know if there is a relationship between sex, relationship status, and balloon size. I predict that single males inflate their balloons the most, though there might well be other sorts of data worth gathering in this context.

Anyone?

Reference

Zehavi, A., & Zahavi, A. (1997). The handicap principle: A missing piece of Darwin’s puzzle. Oxford University Press.

Age & Sexual Coercion

On Thursday of last week, I gave what I find to me one of the most difficult lectures to give in my Evolutionary Psychology class, focusing on sexual coercion and rape. The difficulty isn’t only because of the controversy that surrounds evolutionary approaches to the topic, but for me I find it very difficult to talk about because of the nature of the topic itself. It is, I think, important to discuss, but there is horror behind the numbers that makes the presentation a particular challenge.

This year, as I often have in the past, I left time at the end of the class for students to ask questions and comments; also as in the past, several students came up to the front to speak to me individually after the lecture. I found the students’ remarks and questions insightful and illuminating. I thought I would share parts of the conversation.

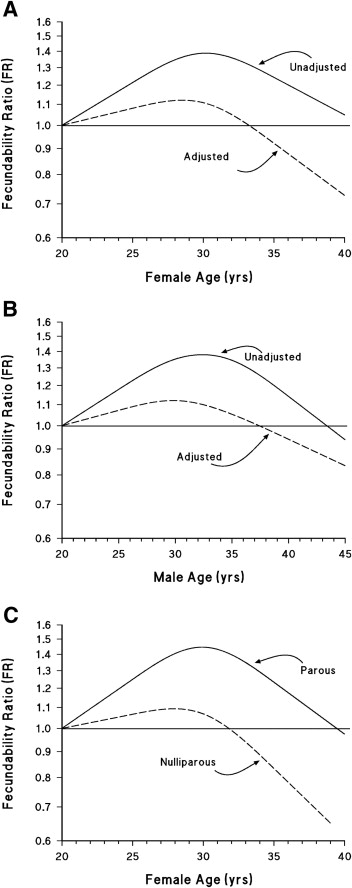

Figure from Rothman et al.

I didn’t systematically poll the students, but at minimum a minority of students came to class with the assumption that rape is motivated by the desire to control or exert power over women. I discuss this idea, most famously associated with Susan Brownmiller, briefly in my lecture, mostly in the context of asking the students to think about what predictions such a view makes. Because the topic is sensitive, while I try to present some relevant data, I try not to push them too strongly toward one view or another. My goal is to get them to think about the relationship between different explanations (both ultimate and proximate) and the existing data.

Other students seemed to come to the discussion with a different view. Perhaps not surprisingly, primed perhaps by my earlier lectures in which I discuss sexual coercion among non-human animals, some students thought that rape might be a short term sexual strategy. Certainly such a view has been entertained in various forms by people working in the area. The proposal is that one way male humans might have increased reproductive success in ancestral environments was through sexual coercion, gaining a single sexual encounter through force instead of through being chosen as a mate. Obviously, much has been written about this and related ideas, with Thornhill and Palmer’s A Natural History of Rape being one early and well-known example.

In class, I asked the students to think about what predictions a short term sexual strategy view makes, in particular with respect to the issue of, if this were correct, which individuals you would expect to be targeted most frequently, holding everything else equal (which is, obviously, an important caveat). The answer, it seems to me – and I’m happy to be corrected – is that the most targeted individuals ought to be those individuals with properties that correlate with the maximum probability of conception given a single act of intercourse (i.e., high fecundity).

This idea intersects with a new paper that crossed my path, a study of “fecundability” in a large sample in Denmark. Fecundability refers to how likely conception is during one menstrual cycle if a woman is having unprotected sex during the course of the cycle. It’s not a perfect measure for the present purpose, but here I take it as a good proxy for the probability of conception during a single sexual act. I’ve included Figure 1 from the paper here. The data show, as one observes in substantial numbers of other similar datasets, that this value peaks in the late 20’s. Here is the authors’ conclusion:

In our study, peak fecundability was approximately 29–30 years among parous women and 27–28 years among nulliparous women. Among parous women, age was associated with increasing fecundability until age 30 years, after which it decreased.

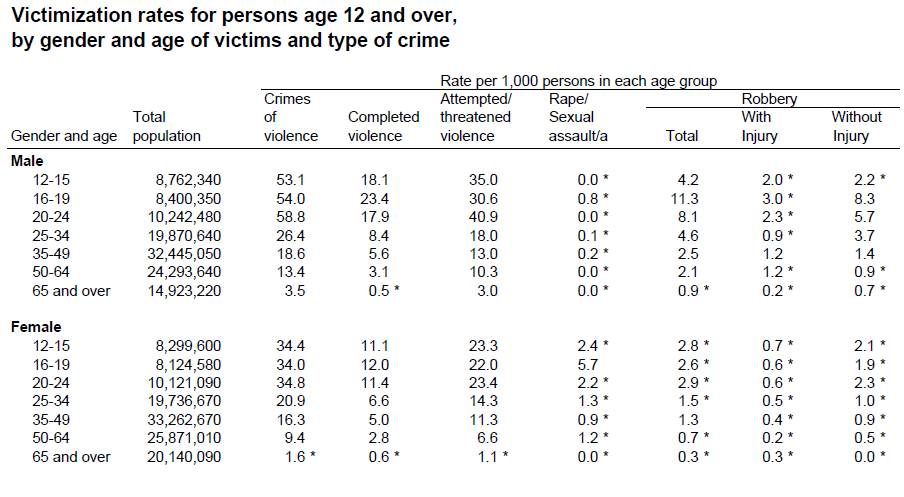

I presented some older data in class, showing largely the same pattern, and I asked the students to consider these findings in the context of statistics regarding the age of victims of rape. The most recent Bureau of Justice statistics I could find were quite old, dating from the late nineties, but I have no reason to believe that the patterns have changed greatly. (If someone has more recent data, please let me know where to find it.) In the BoJ data, roughly 37% of victims are 17 or younger. 62% are age 24 and younger.

Source: Criminal Victimization in the U.S., 2005. Dept. of Justice.

If one thinks that rape is a short term strategy, then one might predict that victims should be deferentially likely to be those individuals most likely to conceive given one act of sex. The Bureau of Justice data make it appear as if targets of rape are considerably younger than this. The median age of a rape victim is 22.

There are, of course, good explanations for why younger, rather than older, women might be targeted. Insofar as age and wealth are correlated, older women are in a better position to be able to afford protections that reduce exposure to the risk of rape. Similarly, as women age, they might learn strategies that make them better able to defend themselves. Other explanations are possible as well. These different explanations make predictions which some might already have tested. For example, if the issue is that one gets safer, in general, with age, then similar patterns should emerge when one looks at other violent crimes. For assault, armed robbery, and murder, does the pattern look similar? Above, I’m showing some data from the Bureau of Justice from 2005, which allows a comparison of robbery and sexual assault broken out by age and sex. To my eye, the robbery data look relatively uniform across age for female victims, but the sexual assault data seem to have a spike at 24 years old and below. Again, I would be pleased if readers directed my attention to appropriate sources which might provide better evidence.

Age is, of course, not the only property of victims that might merit scrutiny. However, because the proposal that rape is a short term sexual strategy seems to point to age as an important parameter, it seemed to me a good place to direct my students’ attention as they considered this issue.

My reading of these data is that victims of rape tend to be younger than one would predict under the proposal that rape is a short term sexual strategy designed to maximize the chance of conception in a one-time sexual encounter. This is not necessarily fatal to the proposal insofar as perpetrators might prefer such victims but choose younger victims for some of the reasons indicated above, or for any of a number of other reasons.

I also alluded to one other set of findings. In a short paper published in 1982, Wislon and Durrenberger report some surprising findings regarding the chances that a victim will date their attacker:

…39% of 52 rape victims as contrasted to 12% of 58 attempted rape victims dated their attackers again, after the assault…

Similar proportions have been reported in more recent data (Ellis et al., 2009), a finding that, I believe, also came as a surprise to my students, as they did to me the first time that I encountered them.

Before concluding, a few caveats. First, by talking about rape, broadly, above, I don’t mean to imply that it’s an undifferentiated, homogenous set of acts. Different motives might very well be at play in different cases, and indeed I find that to be very likely. Second, I’m not trying to speak here directly to the adaptation/byproduct discussion that surrounds this issue. Like so many observers of this debate, it seems to me that this issue is still to be established one way or the other, and I don’t find myself convinced in either direction.

Lastly, it ought to go without saying, but to be clear, an explanation for rape is in no way condoning the behavior. Rape is a horrible crime, and the perpetrators are responsible for their actions; understanding their motives does not excuse the behavior in the least. At the end of class, I ended with some slides that deviate from my usual practice of staying away from non-scientific issues, and I showed some statistics regarding how likely a rapist is to be caught, arrested, convicted, and jailed. (These statistics are aggregated in sites like this one, for instance.) These statistics are sobering.

CITATIONS

Ellis, L., Widmayer, A., & Palmer, C. T. (2009). Perpetrators of sexual assault continuing to have sex with their victims following the initial assault. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 53, 454-463.

Rothman, K. J., Wise, L. A., Sørensen, H. T., Riis, A. H., Mikkelsen, E. M., & Hatch, E. E. (2013). Volitional determinants and age-related decline in fecundability: a general population prospective cohort study in Denmark.Fertility and Sterility.

Wilson, W., & Durrenberger, R. (1982). Comparison of rape and attempted rape victims. Psychological Reports, 50, 198.

Request for Data on Changes Across the Menstrual Cycle

I’m passing along this request for data from Martie Haselton and colleagues. – RK

Meta-analysis of fertility cues: Requesting unpublished papers, presentations, and data on detectable changes in women across the menstrual cycle

Kelly Gildersleeve, Melissa Fales, and I aim to conduct a systematic, quantitative review of the literature on “fertility cues” (detectable changes in women across the ovulatory cycle) to address the question of whether there are detectable changes in women around the time of ovulation as compared with less fertile days of the cycle We would greatly appreciate your help in locating unpublished data to include in our meta-analysis. Please email us at martiehaseltonlab@gmail.com with any unpublished papers, presentations, or data that might meet the inclusion criteria listed below. We will use your data only for the purposes of this meta-analysis and are happy to discuss precisely how we would use your data prior to you sharing it with us.

Inclusion criteria:

(1) Study must have collected information that was used or could be used to estimate female participants’ position in the menstrual cycle (e.g., date of last menstrual onset).

(2) Study must have included only regularly-cycling women (here defined as women who were not using any form of hormonal contraception and were not pregnant, breastfeeding, or aware of cycle abnormalities at the time of their participation) or collected data that make it possible to examine regularly-cycling women separately from other women.

(3) Study must have collected 3rd-party ratings, direct measurements, or self-reports of some physical trait or behavior in women that is potentially detectable by others. For example, previous studies have examined associations between women’s menstrual cycle position and body scent attractiveness, vocal attractiveness, vocal pitch, facial attractiveness, gait, clothing revealingness, body symmetry, etc.

We prefer to be over-inclusive at this early stage of our literature search, so please do let us know of any papers, posters, or data that might meet the above criteria (including papers in press, dissertation or masters thesis work, student projects, conference presentations, etc.).

If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to email us at martiehaseltonlab@gmail.com. Please note that this is a shared email account between the authors of this meta-analysis (Kelly Gildersleeve, Martie Haselton, and Melissa Fales).

Thanks so much for your assistance with this project!

Best,

Martie Haselton, Ph.D.

Professor

Departments of Psychology and Communications Studies

University of California, Los Angeles

haselton@ucla.edu

310-206-7445

Kelly Gildersleeve, C.Phil.

Graduate Student

Department of Psychology

University of California, Los Angeles

kellygildersleeve@gmail.com

Melissa Fales, M.A.

Graduate Student

Department of Psychology

University of California, Los Angeles

melissafales@gmail.com

Please send data to martiehaseltonlab@gmail.com

Postdoctoral Position in Moral Psychology in Paris

Advertisement for a postdoc, via Nicolas Baumard:

The Institute of Cognitive Sciences (Ecole Normale Supérieure) is searching for a postdoc to begin working in September 2013, on a newly awarded grant, “The Evolution of Fairness: An Interdisciplinary Approach” (see summary description below). The successful candidate will be part of a newly created team of evolutionary biologists and experimental psychologists, and will conduct experiments on moral judgments (moral dilemmas, distributive justice, punishment, etc.) in the framework of the theory of fairness and partner choice.

Candidates should have substantive expertise in experimental psychology, and a strong interest in evolutionary psychology and moral philosophy. French is not required (the working language at the Institute is English).

The precise salary level is still being formulated, but will be in the neighborhood of 2400 €/month (including social security and health insurance). Of note for postdocs with children is that the French system also provides free public schools (from age 3) and financial aid for daycare.

Applications should consist of a 2-3 page cover letter, relating the applicant’s training to the project, as well as a full CV, and should be received by April 15, 2013, sent directly to Nicolas Baumard at: nbaumard@gmail.com.

Summary of Grant Focus and Activities

What makes humans fair? This question can be understood either as a proximate ‘how’ question or as an ultimate ‘why’ question. The ‘how’ question is about the mental mechanisms that produce judgments of fairness, and has been investigated by psychologists and social scientists. The ‘why’ question is about the fitness consequences that explain why humans are endowed with a sense of fairness, and has been discussed by evolutionary biologists and behavioral economists in the context of the evolution of cooperation. Our goal is to contribute to a fruitful articulation of such proximate and ultimate explanations of fairness. Using evolutionary models, we will develop an approach to fairness as an adaptation to an environment in which individuals are in competition to be recruited in mutually advantageous cooperative interactions. In this environment, the best strategy is to share the costs and benefits of cooperation in a fair way. Using experimental methods, we will investigate the patterns of fairness judgments both developmentally and cross-culturally and examine whether they conform to the predictions of evolutionary models.