Requirements: Windows install media (7 or 10. 8.x?), desired apps for the image (Office, PDF viewer, web browsers, plugins), virtual machine software (VMware Workstation, Microsoft Hyper-V, or Oracle Virtual Box), and image creation and deployment software (ImageX.exe, MDT, SCCM).

Almost every place I have ever worked, IT had or needed a method to clone and deploy a specific Windows configuration and application set. From a few PCs, to hundreds, the requirements were the same, to deploy the same configuration with as little, repetitive work as possible. The ideal target being what Microsoft calls “zero-touch” deployments that require no interaction on the target computer whatsoever. This is offered by Microsoft System Center (SCCM) along with the Deployment Toolkit (MDT). Many shops do not operate that way, and have some level of interaction required during the imaging process. This piece will discuss creating a Windows install for distribution.

What you’ll need…

Windows and software install media (obviously)

Virtual machine software for the creation workspace. Why? Two reasons. First, virtual machines provide the option to create hardware-neutral images which can be applied anywhere, regardless of what is actually in the target computer. One image becomes possible for multiple hardware configurations. This also involves less work in mainatining the image as any work only needs to be done once and not x-times per different type of hardware. Second, most virtual machine software (I’m not sure about Virtual Box) have the ability to save a VM’s state, and revert back to that state, should it become necessary. VMware calls these “snapshots”, and Microsoft uses the term “checkpoint” in Hyper-V. Should a screw-up occur, it can be undone without loosing work or have to re-do everything. These are two facets that are simply not available with building images on real hardware. Test on real hardware, but build in a virtual environment.

- VMware Workstation is pricey, but well worth the cost IMHO.

- Hyper-V comes with Windows Server 2008 and later, Pro and Enterprise versions of Windows 8, 8.1, and 10 as “Client Hyper-V.”. The build computer’s CPU must support hardware assisted virtualization for Windows to install the Hyper-V role. Intel Core 2 Duo/Quad CPUs won’t muster.

- Virtual Box, now owned by Oracle, is a freebie. I haven’t used Virtual Box very much outside of general curiosity.

The build workstation has to have some power to it. Nothing extravagant like an Alienware, or Falcon Northwest gaming rig, but above average. Try to avoid using a laptop as a VM build station. Laptops are great for testing, but a desktop PC is optimal. Don’t use a Mac. I love my MacBook Pro, but it isn’t meant for making Windows images. A quad-core CPU (Intel Core i5/i7, or AMD Phenom series) will work for starters. The more powerful, the better. RAM is the key. The more the better. I routinely work with 16GB of RAM on my workstation (the most it’ll take), and it can handle three running VMs and the host OS before going wacky. 32GB of RAM is not ridiculously expensive today, and well-worth the couple-hundred extra bucks. VMs take up storage space quickly. Working on several VMs, it is not difficult to fill a 2TB HDD (I’ve done it). Those are not that expensive either, and 2TB is the starting point I’d go with for a virtualization rig. Anything more, and you have to make sure your PC supports UEFI vs. BIOS, or else all of the drive’s space will not be recognized by the firmware, and Windows. Working from USB storage might fly, but the throughput won’t match that of internal storage, and you’ll have a bottleneck. My VM creation setup, however, is backed-up every night to my trusty 4TB WD USB HDD. If you can get large-capacity SSDs instead of traditional rotational drives, do it, but don’t sacrifice space for speed. An SSD for the boot volume with Windows and apps along with a large 2TB+ traditional HDD for VM storage is a nice setup, and not fiscally unrealistic.

Virtual Machine Setup…

Create a new VM that will become your Windows image. For Windows 7 and later, I recommend 4GB of RAM, 1 CPU with 2 virtual cores (if possible), and a virtual hard drive the size of the smallest drive that will ever receive the image. We have some 128GB SSDs out there, so 128GB is my vHDD size. That’ll assure the image will fit everywhere you intend to deploy it. Now, it is easy to see how fast space will go on your drives. Everything else is fine with the defaults. Bridged vs. NAT network adapter? It doesn’t really matter even for network-based capture/deployment. I’ve used both and have noticed no speed differential.

Install and Configure Windows…

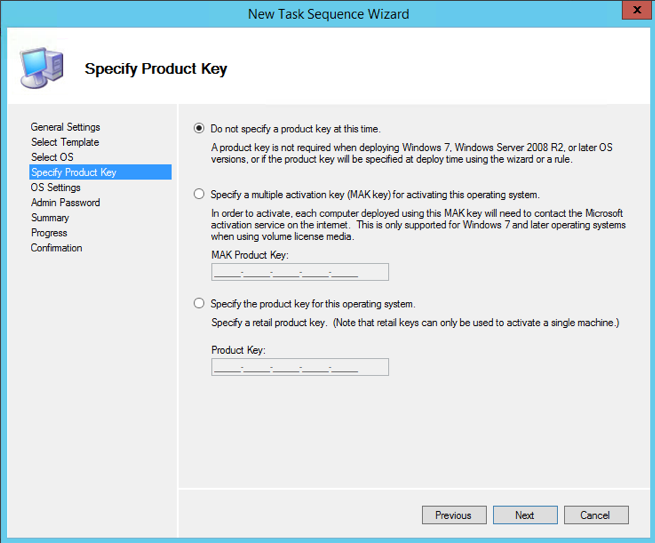

Install Windows onto the VM with all of the default settings. If you’re lazy like me, you can use an unattend file to answer all of those pesky setup questions. This site, the Windows Answer File Generator, has a GREAT web UI for creating unattend.xml files that WORK. Place the unattend file at the root of your install media and let Windows install itself. The whole process for Windows 7-10 should be 20-30 minutes. Don’t bother with the product key and activation. Sysprep will just strip that out in the end. If your build process takes longer than a month, you might need the key and activation. I’ve never run into that problem. Don’t join any active directory domains. Sysprep will quit if it is run on a domain-joined PC.

Next, power-down (not sleep, hibernate, or pause) the VM and create a snapshot or checkpoint. This will save you 20-30 minutes of re-installing should a foul-up occur. Power back on and go into Programs and Features (Windows 7) and add/remove all of the stuff that is not needed. I get rid of the tablet components, XPS printer/viewer, Windows Media Center, Windows Fax and Scan. All of the stuff I know the end users will not touch.

Update Windows/Office…

Before getting into the nitty-gritty of configuration, completely update Windows through Microsoft Update. The older your version of Windows, the more updates it will need, and the longer the update process will take. A fresh install of Windows 7 Enterprise SP1 x64 from MS VLC ISO required 296 updates before no more were required (as of February 2016). This will take about a day (8+ hours) to complete. One might think about adding MS Office into this process to allow it to join in the update process, but there is a reason not. Take this opportunity of having a clean install of Windows, updated, and use it as a template for other VMs. VMware Workstation allows VMs to be cloned and copied, so a patched copy of Windows can serve as a starting point for other virtual machine projects. A MAJOR time saver. Completely update Windows until it screams “no more” and shut down, then take a snapshot.

Clone or continue? That’s up to you, but whatever is chosen, the next part is installing MS Office (if needed. I can’t imagine it wouldn’t), and completely updating that through Microsoft Update. I do a custom install of Office to not include the programs users won’t need, like Infopath, and Lync, Skype for Business, and OneDrive for Business. YMMV. Microsoft Office 2013 Pro Plus needed 151 updates to be complete from a fresh install of the MS VLC ISO. Again, I wouldn’t bother with product keys or activation for Office. Shut down and take a snapshot when that part is done.

Application Installs…

Add all of the applications that need to be deployed with the image. Here is where the question of thin image vs. thick image is contemplated. A thin image contains just the bare essentials needed to get started with many other apps installed at distribution. Programs that change often, and would require updating/re-capturing the image are best left to installation at deployment. Candidates for this include Adobe Flash Player, Shockwave, AIR, and antivirus software. Software that has first-run settings which must be answered for the end user should be placed into the image, and not installed at deploy time. We install many apps with our image, so this process takes us about as long as it does to update Windows and Office. A good example set to start would be: Mozilla Firefox ESR, Google Chrome Enterprise, Adobe Acrobat Reader, Quicktime Player, VLC Media Player, Microsoft Silverlight, Visual C++ Redistributables 2005-2015, Skype and 7-zip. Run each and every newly-installed application to make sure they work as intended, and then delete the downloaded installers. The plugins, and antivirus (SEP) will be installed when the image is deployed. Power-down the VM and take another snapshot.

By this point, we have a basic working install of Windows which is moderately useful and could probably be distributed to end users. One question does arise which is substantial in nature, and determines how next to proceed. Does a custom default user profile need to be created and configured? If yes, we need to do that before capture.

Customizing a default user profile…

Windows, by itself, works pretty well out of the box, but comes with a myriad of first-run dialogs and prompts which can be confusing. My target audience is public computing, classrooms, kiosks and labs. For privacy reasons, user profiles are not kept on the computers. As soon as a user logs off from Windows, their profile is removed. Each time someone logs into one of the computers I am responsible for administering, they are logging in for the first time. Any and all first-run dialogs/prompts that can appear will. The option to spend 10-15 minutes of a 60 minute class, getting the software to work as desired, and out of the way is just not an option. To prevent this, I try to configure as much for the end user in advance as possible. Group policy is my hero in this effort. Almost anything can be set for the computer or a user through a GPO. The exceptions being non-Microsoft software like MATLAB, Maple, and Stata that all have first-run issues which often require administrative intervention. I don’t let users run as admins.

Sysprep is the utility Microsoft has made available for generalizing an installation of Windows since Windows 2000. Starting with Windows Vista, Microsoft changed to an image-based installation and mmaintenance process. Sysprep changed too, and became much more difficult to use (for me anyway). It is at this time that copying a customized user profile to the default required the use of an unattend.xml file. With Windows 2000 and XP, you could actually just copy it and everything would be fine. In the specialize pass (No. 4) of the unattend.xml file there is an option to add a pass called “CopyProfile” to the “Microsoft-Windows-Shell-Setup” setting that will copy the built-in administrator account’s profile to the default. The trick is when to apply this, during capture, or during deployment? That depends on how you’re capturing and deploying, but either way the built-in administrator account is what I use as a template for my custom default user profile.

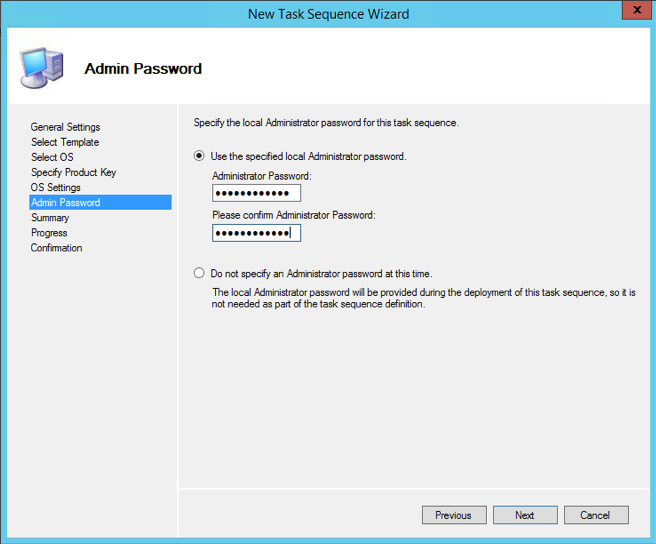

Enable the built-in administrator account and give a password you’ll be comfortable with entering dozens of times. Log in as the admin, and immediately delete the profile for the other account setup asked you to make after installing Windows. The reason for this is that CopyProfile will not copy the admin’s profile if another profile exists on the file system at the time the copy takes place (experience speaking here). Delete the profile from the advanced system properties window, and not by just deleting the folder under C:\Users. Other accounts can remain, they just cannot have profiles.

As the built-in admin, configure the Windows environment they way you want the end users to have it. Again, most of these tasks can be accomplished with a domain-based GPO. Run each and every program the end users are likely to use and answer any first-run dialogs and prompts. DO NOT surf the web as the built-in administrator on a Windows PC without antivirus software for obvious reasons, but an important another is profile size. Surfing with Chrome or Firefox even on just a couple of sites and will add megabytes of data to the profile. You could probably get away with not even running any of the browsers at all with a good GPO in place. Google, Mozilla, and of course Microsoft make GPO settings available to completely configure each piece of software and eliminate any first-runs. Adobe recently made an admx template for configuring Acrobat Pro and Reader via GPO. GPO templates exist for Microsoft Office 2007-2016, with a dizzying array of possible configuration options. Those and the settings for Windows will get 95% of end user configuration done in a customized profile.

Things that are easily set include the desktop wallpaper and icons, the start menu, screensaver, power options, and remote desktop settings. Take your time and run through each usage scenario, if possible, without puffing up the profile’s size. Large user profiles take a while to create at log in, and lengthen the log in time required to get started. In my case, every is logging in for the first time, so their profile will be created when the need to use the PC. A 500MB profile will slow that entire process down. Once things are as desired, power the VM down and take a snapshot. This snapshot is a failsafe point for return after the image has been captured.

Capturing the Image…

There are several different ways to get an image of Windows. Traditionally, Norton (Symantec) Ghost was the standard for deploying Windows operating system images. After acquisition, Symantec let the product stagnate over a period of years as Microsoft developed successive versions Windows, and it became necessary for us to switch to a solution that would natively support later versions of Windows PE. We adopted MDT a couple of years ago for a few reasons, and that allowed us to change the way we made operating system images. Driver support in Ghost is not real versatile. The option to create one image for multiple hardware configurations required substantial tweaks and endless trial and error testing Ghost was designed to have one image per hardware type, with all of the drivers included in the image. This is not that big of a deal since many large IT outfits only support a few different types of hardware models and configurations. For us, that was six different images for a single type of Windows install (Windows 7 Pro x64). Needless to say the images did not get updated too often due to the amount of work involved.

Removing the hardware dependence and creating hardware-neutral images was a requirement for our new imaging software. An install in a virtual machine allows that type of neutrality.

Boot the VM to be captured an log on as the built-in administrator, the one that was pre-configured before. From the advanced system properties, delete every other user profile on Windows. The accounts can stay, but the profiles cannot. If there are any VM-dependent software like VMware Tools, or Hyper-V Integration services installed, uninstall them. If there are mapped drives between the host and guest OS, power-down the VM, remove them, and restart.

I like to clean Windows before capture by running a few command prompt executables.

Go to %TEMP% from the Run dialog and delete everything there that can be deleted.

Open an administrative command prompt and run the following commands.

Delete any and all shadow copies.

vssadmin delete shadows /All /Quiet

Get rid of any downloaded software updates.

del c:\Windows\SoftwareDistribution\Download\*.* /f /s /q

Delete any hidden Windows install files. Chances are there are none, but it cannot hurt to check.

del %windir%\$NT* /f /s /q /a:h

Delete the Windows prefetch files. There also probably none of those either.

del c:\Windows\Prefetch\*.* /f /s /q

Run disk cleanup.

c:\windows\system32\cleanmgr /sagerun:1

Defragment the C:\ drive (It shouldn’t be that fragmented).

defrag c: /U /V

Clear the Event Logs. Execute one command on each line.

wevtutil el 1>cleaneventlog.txt

for /f %%x in (cleaneventlog.txt) do wevtutil cl %%x

del cleaneventlog.txt

Flush the DNS cache.

ipconfig /flushdns

NOW! We’re ready to capture. The question is how?

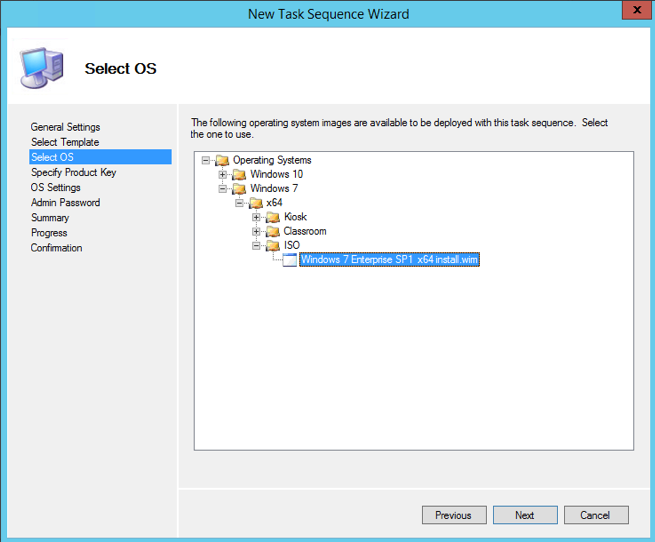

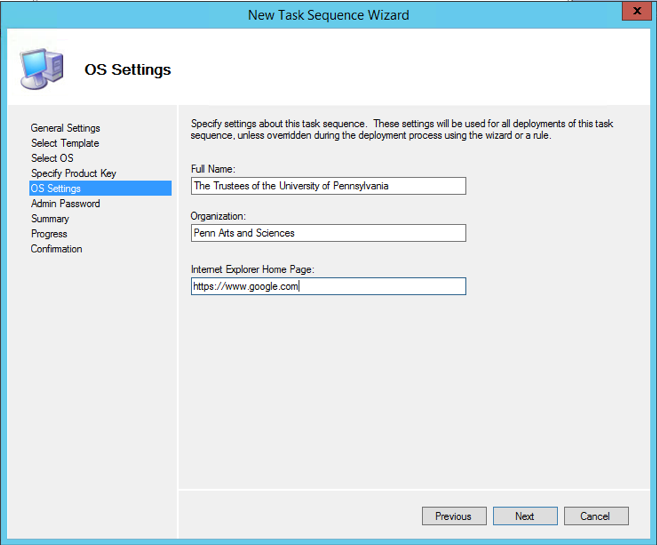

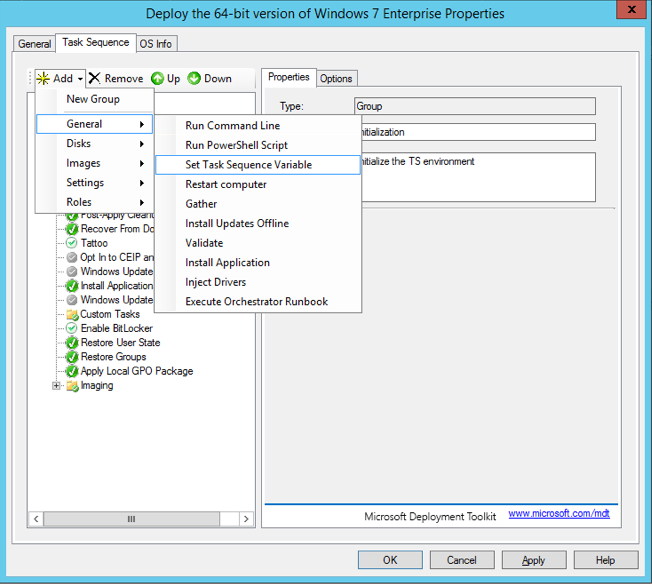

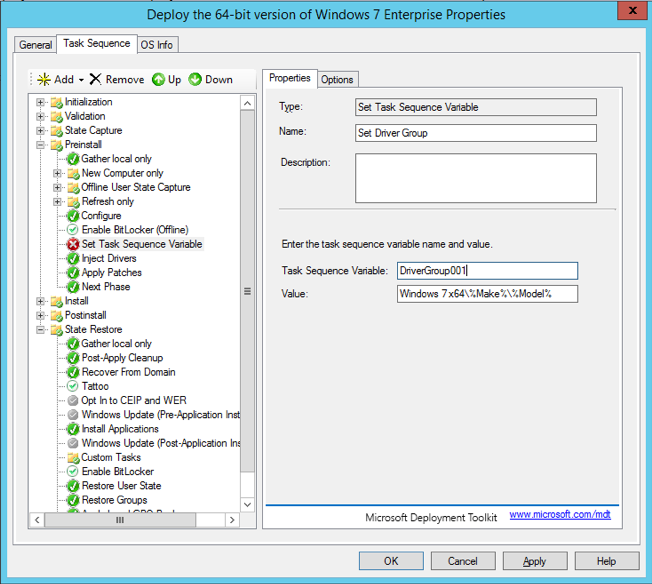

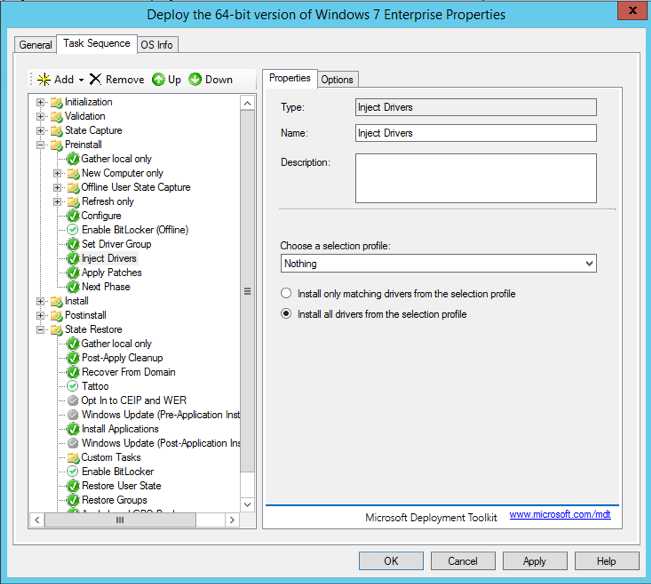

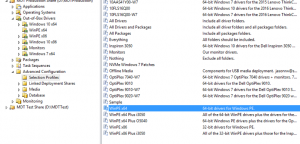

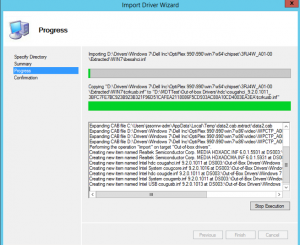

We use MDT for imaging. MDT has a special type of task sequence called “Sysprep and Capture.” To kick this off, from the install of Windows to be captured, navigate to \\mdtserver.domain.com\DeploymentShare$\Scripts and run LightTouch.vbs. This will connect to the deployment share, and start the process. Enter any credentials required, select the appropriate task sequence, and give the image a name, then begin. Capturing from a VM to an actual MDT server, over the network, will take a while. Even for small images, it is best to just let the task run and not use the build computer for anything else until it is finished. I do this at the end of the day, when I’m not going to be needing to use the computer.

Once the image has been captured, the VM will restart and wait for further action. At that point, power-down the VM, and roll back to the last snapshot taken before the VM was captured. Back to not-so-square-one, and ready to re-capture, update, or whatever when necessary.

Outside of MDT, it is possible to capture with just a Windows PE boot disk with ImageX.exe. This process is not a clean and automatic as MDT, but it works. Going that way, the pre-capture setup process goes a little differently. In its most basic form, you need to only run sysprep from the VM about to be captured, and shut down, then restart to the WinPE boot disk and run ImageX.exe. To copy the default user profile this way, an unattend.xml file needs to be used with sysprep and the CopyProfile option must be set to “True.” The unattend file is only needed if there are any customizations that need to be applied when the image is applied to a computer. Large capacity USB flash drives are very affordable. I have a 128GB USB drive, that I purchased for $29.99, configured as a WinPE boot drive, and can be used to capture images directly to the drive instead of over the network, as it is usually done.

Enjoy!